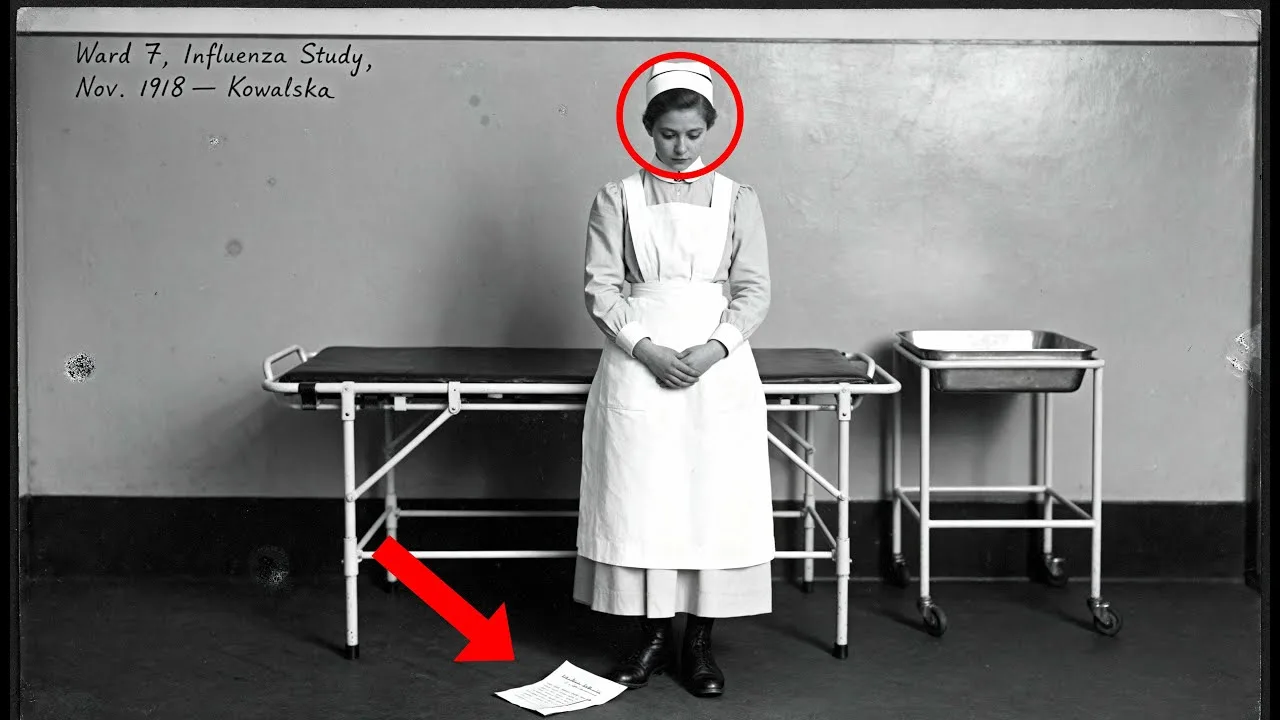

This 1918 portrait of a nurse’s assistant looks ordinary until you see the paper under her shoe.

It seemed like nothing more than a hospital publicity image, the kind taken by the dozen during the Great War to reassure families that their wounded soldiers were in good hands.

A young woman in a crisp white uniform stands beside an empty stretcher, hands folded in front of her, eyes cast slightly downward.

She looks nervous, which would not be unusual for someone unaccustomed to being photographed.

The lighting is flat, institutional.

The background is a bare wall.

Nothing about this picture should have kept anyone awake at night.

But Dr.

Elena Vasquez could not stop looking at the floor.

She had been sorting through a donor acquisition at a medical history archive in Chicago when she first pulled the print from its acid-free sleeve.

The collection came from the estate of a retired hospital administrator, a man who had spent 40 years gathering documents, photographs, and ephemera related to the city’s medical institutions during the early 20th century.

Most of it was mundane.

Staff portraits, groundbreaking ceremonies, posed shots of doctors in white coats looking authoritative beside new equipment.

Elena had cataloged hundreds of similar images over her 12 years at the archive.

She knew what to expect.

This one was different.

At first, she thought there was damage to the print, a dark smudge near the bottom right corner, partially obscured by the assistant’s shoe.

Elena tilted the photograph toward the light, assuming she was looking at a water stain or a chemical artifact from the developing process, but the edges were too crisp, too deliberate.

She reached for her magnifying loop and leaned closer.

It was paper, a folded document, maybe 2 in visible, pressed flat against the wooden floor by the heel of the woman’s shoe.

The woman’s left foot was positioned at an odd angle, as if she had shifted her weight suddenly and then frozen in place.

Elena could just make out a fragment of typed text and what might have been a signature line.

She set the photograph down and looked at it again from a normal distance.

The woman’s expression no longer seemed merely nervous.

it seemed caught.

Elena Vasquez was not the type of researcher who believed in dramatic revelations.

She had spent more than a decade studying the history of public health in American cities with a particular focus on the immigrant communities that had provided so much of the labor in hospitals, asylums, and clinics.

She had seen photographs of orderlys, laresses, kitchen workers, and nurses aids from every decade between 1870 and 1950.

She knew how to read the visual grammar of institutional photography, the way it flattened individuals into types, erased names, and positioned workers as background to the real subjects of the frame.

She was used to looking past the surface, but she’d never seen someone step on a document in the middle of a photograph.

She turned the print over.

On the back, in faded pencil, someone had written a partial notation.

Ward seven, influenza study, November 1918.

Below that, in different handwriting, was a single word that had been partially erased, but was still legible.

Kowalsska.

Ellena set the photograph aside and opened her laptop.

She had work to finish on other projects.

But her eyes kept drifting back to that folded paper, that nervous face, that strange frozen posture.

By the end of the day, she had moved every other task to her secondary list.

She needed to know who Kowalsska was and she needed to know what that paper said.

The first step was obvious.

Elena checked the donor records for anything else connected to Ward 7 or to influenza research during the fall of 1918.

The collection was large, over 40 boxes, and not all of it had been fully processed.

She found a folder labeled staff records 1915 1920 and began working through it page by page.

The hospital in question was one of Chicago’s major institutions, a teaching hospital affiliated with a respected medical school.

During the war years, it had expanded rapidly, adding temporary wards to handle both military casualties and the growing tide of influenza patients.

By November 1918, the month noted on the back of the photograph, the city was deep in the second wave of the pandemic.

Hospitals were overwhelmed.

Staff were dying alongside patients.

Any warm body that could hold a bedpan or change a dressing was pressed into service.

Elena found a payroll list from October 1918.

Near the bottom under the heading temporary assistance ward 7, she spotted the name Marta Kowalsska.

Age 19, nationality listed as Polish.

Address in a workingclass neighborhood on the near northwest side.

Weekly wage of $4.

That was not much money even by the standards of 1918.

Elena made a note to look into comparable wages for similar positions.

She also noticed that Marta’s name did not appear on any payroll lists after December 1918.

Either she had quit, been fired, or something else had happened.

The next clue came from a folder of internal correspondence.

Elena found a memo dated November 22nd, 1918 addressed to the hospital superintendent.

The subject line read, “Concerns regarding Ward 7 research protocols.” The text was bureaucratic and carefully worded, but its meaning was clear enough.

A senior nurse was raising questions about the way patient consent was being obtained for a clinical study involving experimental influenza treatments.

She noted that many of the patients on Ward 7 were recent immigrants with limited English, that the consent forms were written in complex medical and legal language, and that in several cases, the forms appeared to have been signed by someone other than the patient.

The memo ended with a request for guidance.

There was no indication that any guidance had ever been provided.

Elena sat back in her chair.

She was beginning to see the shape of something larger.

A wartime hospital, an experimental study.

patients who could not read the forms they were supposedly signing and a young Polish assistant whose name appeared on the ward’s payroll for exactly three months before vanishing from the record.

She needed help.

She reached out to a colleague at a nearby university, a historian named Dr.

Marcus Oilaren, who specialized in the intersection of immigration and labor history during the progressive era.

Marcus had written extensively about the exploitation of immigrant workers in industrial settings.

Elena suspected he would be interested in what she was finding.

When Marcus arrived at the archive 2 days later, Elena showed him everything, the photograph, the payroll records, the memo about consent.

He studied the image under the magnifying loop for a long time, then set it down and looked at her.

You know what that paper is? he said.

It was not a question.

I think so, Elena replied.

I think it’s a consent form, and I think she was hiding it.

Marcus nodded slowly.

The question is whether she was hiding it from the photographer or from someone else.

They spent the next week pulling every available record from the archive.

Marcus contributed his own expertise, pointing Elena toward census data, immigration files, and city directories that helped fill in the details of Marta Kowalsska’s life.

She had arrived in Chicago in 1913 at age 14, traveling alone from a village in what was then the Russian partition of Poland.

She had worked as a domestic servant for 2 years before finding a job as a laress at a small private hospital.

When the war began and the larger hospital started expanding, she moved to the teaching hospital where the pay was slightly better and the work slightly less grueling.

By 1918, she was working on ward 7 as a nurse’s assistant.

Her duties would have included changing linens, emptying bed pans, helping patients eat, and running errands for the nurses and doctors.

She would not have been trained in medicine.

She would not have been considered a skilled worker.

She would have been in the language of the time, a ward girl, but the record suggested she had been asked to do something more.

Elena found a second memo.

This one dated December 3rd, 1918.

It was written by the same senior nurse who had raised concerns 2 weeks earlier.

This time, her tone was sharper.

She reported that she had witnessed a ward assistant, not named, presenting consent forms to patients who were barely conscious and guiding their hands to sign.

She described the assistant as visibly distressed and noted that when confronted, the assistant had said only that she was following orders from the research physician.

The memo requested an immediate investigation.

A handwritten note in the margin in different ink read, “Discussed with Dr.

H, no further action.” Dr.

H, that was the research physician.

Elena began searching for anyone on the hospital staff whose surname began with H and who was involved in e influenza research during the fall of 1918.

She found him in a medical journal from 1919.

Dr.

Frederick Hollander, an assistant professor of internal medicine, had published a paper in March of that year titled observations on the efficacy of serum therapy in acute influenza pneumonia.

The paper described a clinical study conducted at a Chicago teaching hospital during the pandemic.

It reported that over 200 patients had been enrolled in a trial comparing standard supportive care to an experimental treatment involving injections of serum derived from the blood of recovered influenza patients.

The paper noted that all patients had provided written consent.

It did not mention that many of them could not read English.

It did not mention that some of them were unconscious when the forms were signed.

and it did not mention Marta Kowalsska.

But Elena now understood what the paper under her shoe might have been.

To understand what was happening on Ward 7, Elena and Marcus needed to widen their research.

They began looking at the broader context of medical experimentation in the United States during the early 20th century.

What they found was disturbing but not surprising.

This was an era before the establishment of institutional review boards, before the Nuremberg Code, before any formal system of research ethics.

Doctors who wanted to test new treatments on human subjects often did so with little oversight and even less regard for informed consent.

The patients most likely to be used in such experiments were those with the least power to refuse, prisoners, orphans, the mentally ill, and immigrants.

Marcus introduced Elena to the work of other historians who had documented cases of medical exploitation during this period.

There were studies in which prisoners had been deliberately infected with diseases.

There were trials in which asylum patients had been subjected to dangerous surgeries without their knowledge.

And there were countless smaller experiments never published in which doctors had used their access to vulnerable populations to test theories that would never have been approved if the subjects had been wealthy or white or English-speaking.

The serum therapy trial described in Dr.

Hollander’s paper was not unusual in its methods.

What made it notable was the photograph that had accidentally preserved a piece of evidence.

Elena arranged to visit the site of the old hospital, which had been demolished in the 1960s and replaced by a medical office complex.

Nothing remained of the original building, but she also visited the neighborhood where Marta Kowalska had lived a few miles to the northwest.

The area had changed dramatically over the past century, but Elena found a Polish cultural center that maintained records of the community’s history.

a volunteer archavist there was able to locate a mention of the Kowalsska family in a parish newsletter from 1920.

It was a brief obituary for a man named Stannisl Kowalsa who had died of tuberculosis leaving behind a wife and two daughters.

The older daughter was named Marta.

The obituary noted that she had moved away from Chicago after the war and was believed to be living somewhere in the east.

That was all.

No further details, no explanation for why she had left.

But Elena also found something else at the cultural center, a handwritten memoir deposited in the 1980s by an elderly woman who had grown up in the same neighborhood as the Kowalsska family.

The memoir was mostly concerned with domestic life, recipes, holiday traditions, and family anecdotes.

But one passage caught Elena’s attention.

The author recalled a girl she had known in her youth, a serious and quiet girl who worked at one of the big hospitals downtown.

She wrote that the girl had once confided in her about something terrible that was happening at her workplace.

Patients were being given injections without understanding what was in them.

Some of them were dying.

The girl had been told to help collect signatures, but she knew the signatures were not real.

She was frightened and did not know what to do.

The author did not name the girl, but she noted that the family had been named after a Polish word for a type of bird, a small brown bird that hopped along the ground.

Elena looked up the etmology of Kowalsska.

It derived from the word for blacksmith, not bird, but coowal was close to kala, the Polish word for jackd.

It was possible the author had misremembered or been deliberately vague.

Either way, Elena now had a human voice behind the photograph.

A young woman who knew that what she was being asked to do was wrong, who was afraid, and who had tried to tell someone.

The question was, what had happened to her after the photograph was taken.

Elena returned to the archive and began searching for any records that might explain Marta’s disappearance from the payroll.

After December 1918, she found a termination notice dated December 12th, 1918.

The reason given was insubordination.

There were no further details.

But there was one more document in the folder.

A letter unsigned addressed to the hospital superintendent and dated December 15th, 1918.

The letter was written in slightly awkward English, the kind that suggested a non-native speaker working carefully to express herself correctly.

It accused Dr.

Hollander of forcing ward assistants to forge patient signatures on consent forms.

It named specific dates and specific patients.

It requested that the hospital investigate and take action.

The letter had been stamped received, but there was no indication that any action had been taken.

Someone had written in the margin, “Disgruntled former employee file.” Elena photographed the letter and sat for a long time in the quiet of the archive.

She was looking at the work of a 19-year-old immigrant girl who had risked her job and possibly more to report what she had seen.

And she was looking at the institution’s response, which was to dismiss her as disgruntled and file her complaint away.

The photograph now made sense.

Martya had not stepped on the paper by accident.

She had hidden it on purpose.

Perhaps she had been gathering evidence.

Perhaps she had intended to take that consent form with her to prove what was happening.

But the photographer had arrived unexpectedly and she had frozen, unable to move her foot without revealing what she was hiding.

The camera had caught her in the act of resistance.

Elena knew she had to share this story.

The archive where she worked was part of a larger medical school, and the school had a museum that regularly mounted exhibitions on the history of medicine.

She approached the museum’s director with a proposal, an exhibition centered on the photograph of Marta Kowalsska, telling the story of wartime medical experimentation and the immigrant workers who had been caught in its machinery.

The director was interested but cautious.

The hospital in the photograph was a predecessor of one of the city’s current major medical centers.

Donors from that institution had contributed generously to the medical school over the years.

There would be sensitivities.

Elena pushed back.

The events in question had happened over a century ago.

The people involved were long dead.

The institution itself no longer existed in its original form.

Surely, she argued, the school’s commitment to ethical medicine required an honest reckoning with the past.

The director agreed to convene a committee to review the proposal.

The committee meeting was held in a conference room overlooking the hospital’s modern campus.

Elena presented her findings, walking the group through the photograph, the documents, and the broader historical context.

Marcus joined by video to speak about the exploitation of immigrant labor during the progressive era.

A bioethicist from the medical school discussed the evolution of research ethics and the importance of acknowledging historical abuses.

The response was mixed.

Some committee members were supportive, praising the rigor of Elena’s research and the importance of the story.

Others were more hesitant.

One member, a senior physician with close ties to the hospital’s current leadership, questioned whether the evidence was strong enough to support the narrative Elellena was proposing.

“We have a photograph and some circumstantial documents,” he said.

“We don’t have proof that any laws were broken.” Elellanena replied that the absence of informed consent was itself a violation of the patients autonomy regardless of whether it was technically illegal at the time.

“These were human beings,” she said.

“They deserve to know what was being done to their bodies.” Another member raised concerns about how the exhibition might be perceived by the public.

“People trust this institution,” she said.

“If we present this story without proper context, it could undermine that trust.

And if we hide this story, Elena responded, we are repeating the same mistake that was made in a 190 or 18, we are prioritizing the institution’s reputation over the truth.

The debate continued for over an hour.

In the end, the committee voted to approve the exhibition with the condition that it include extensive contextual material about the broader history of research ethics and the reforms that had been implemented since.

Elena accepted the compromise.

It was not everything she had hoped for, but it was a start.

The exhibition opened 6 months later.

At its center was a large reproduction of the photograph printed at several times its original size so that every detail was visible.

The paper under Marta’s shoe was clearly identifiable now, its typed text and signature line unmistakable.

Beside the photograph was a panel explaining who Marta Kowalsska was, what had happened on Ward 7, and what the document under her foot likely represented.

The exhibition also included reproductions of the key documents Elena had found, the payroll records, the memos from the senior nurse, the termination notice, the unsigned letter of complaint.

Visitors could trace the paper trail and draw their own conclusions.

But the most powerful element of the exhibition was the voices.

Elena had partnered with a community organization that worked with Polish-American families in Chicago.

Through their networks, she had located a woman in her 80s who believed she was a distant relative of Martya Kowalsska.

The woman, whose name was Ireina, did not have definitive proof of the connection, but she had family stories that matched the details Elena had uncovered.

She remembered hearing as a child about an aunt or great aunt who had worked in a hospital during the great sickness and who had gotten in trouble for speaking out.

Ireina was invited to speak at the exhibition’s opening.

She stood before the photograph and studied it for a long time.

Then she turned to the audience and said in a voice that was quiet but steady, “She was just a girl.

She did not have power.

She did not have money.

She did not have a name that anyone would remember.

But she knew what was right and she tried to do it.

That is what I want people to see when they look at this picture.

The exhibition drew significant local attention.

Several news outlets covered the story, focusing on the history of research ethics and the ongoing debates about informed consent in medical studies.

The medical school received both praise and criticism.

Some alumni complained that the school was airing old scandals that should have stayed buried.

Others applauded the institution’s willingness to confront its past.

For Elena, the most meaningful outcome was quieter.

A few weeks after the exhibition opened, she received an email from a graduate student at a university on the East Coast.

The student was researching the history of Polish immigrant communities in New England and had come across a brief mention of a woman named Marta Kowalsski with a slightly different spelling who had worked as a domestic servant in Massachusetts in the 1920s and 1930s.

The woman had never married and had died in 1972.

She had left behind a small collection of personal papers now held by a local historical society.

Elena contacted the historical society and asked if they could check for any documents related to the woman’s earlier life.

A few days later, she received a scanned image of a single sheet of paper yellowed and fragile.

It was a hospital payub from November 1918 issued by the same Chicago teaching hospital made out to Marta Kowalsa.

The woman on the east coast was the same woman in the photograph.

Elena stood at the window of her office and looked out at the city.

Somewhere beneath the modern skyline, the old hospital had stood.

The wards had been full of dying patients.

The doctors had been racing to find a cure, and a 19-year-old girl from a village in Poland had tried to protect people who could not protect themselves.

She had lost her job for it.

She had been dismissed as disgruntled and filed away.

She had left Chicago and started over, far from anyone who knew what had happened.

She had lived out her life in obscurity, never knowing that a photograph she had tried to hide had preserved her act of defiance for a century.

Old photographs are never neutral.

They are always performances staged for the camera framed to tell a particular story.

The respectable family portrait, the institutional publicity shot, the celebration of progress in order and civilization.

These images were designed to project power and permanence to assure viewers that everything was as it should be.

But sometimes in the margins something slips through.

A hand positioned at an odd angle.

A reflection that shows too much.

A paper folded under a shoe.

These are the moments when the careful staging breaks down.

When the reality behind the image pushes through.

They are easy to miss if you are not looking.

Most people glance at an old photograph and see only what they expect to see.

A frozen moment from a distant past, quaint and slightly foreign, bearing no connection to the present.

But every photograph is also a document.

And every document can be read.

There are thousands of images like this one sitting in archives and attics and museum basement across the country.

Portraits of domestic servants standing behind the families they worked for.

group shots of factory workers lined up in front of machines, publicity photographs of institutions that claimed to be helping the people they were actually exploiting.

Each of these images contains details that someone did not mean to preserve.

Each of them is waiting to be read.

The photograph of Marta Kowalsska hung in the exhibition for a year.

Then it was returned to the archive carefully stored in its acid-free sleeve, cataloged with a new and fuller description.

Visitors to the archive can still request to see it.

Most do not.

It is, after all, just a picture of a nurse’s assistant standing beside a stretcher.

But if you, if look closely, you can see the paper under her shoe.

And if you look even closer, you can see her face.

She is not just nervous.

She is making a choice.

She is choosing in that frozen moment to hide evidence of something wrong.

She is choosing to resist.

And she is trusting that someday someone will

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load