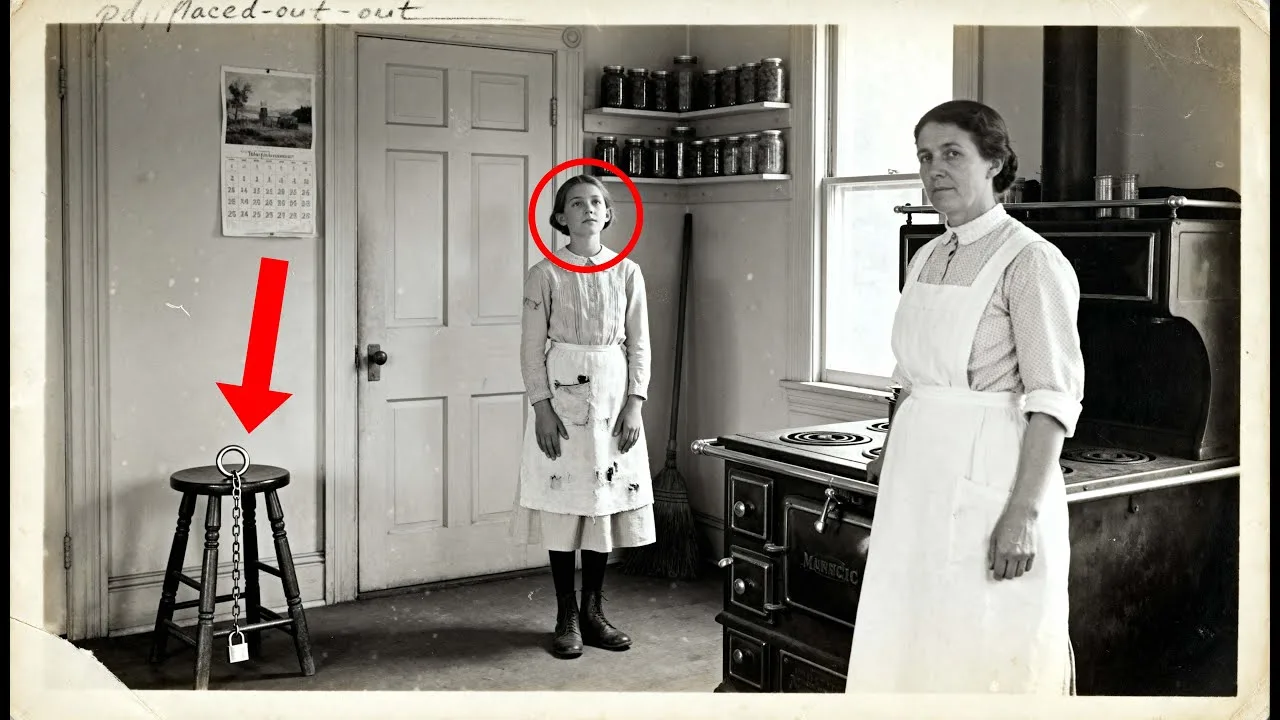

This 1911 farmhouse portrait looks wholesome until you notice the lock on the stool.

It seemed like a simple kitchen scene.

A farm wife standing proud beside her stove.

A teenage girl in a clean apron positioned just behind her shoulder.

The kind of image that ends up in local history books with captions about pioneer spirit and simpler times.

Until one detail refused to stay in the background.

until a brass fitting in the corner of the frame opened a door into something far darker than anyone wanted to believe.

Miriam Ostrander had been cataloging photographs for the Dawson County Historical Society for 11 years when the image arrived in a cardboard box from an estate sale outside Lexington, Nebraska.

The box contained the usual mix.

cabinet cards with water damage, tin types too corroded to save, a handful of real photo postcards showing Main Street storefronts that no longer existed.

She worked through them methodically, entering dimensions and estimated dates into her spreadsheet, setting aside anything that might be worth a conservation budget she did not have.

The kitchen portrait was unremarkable at first glance.

A gelatin silver print approximately 4x 6 in mounted on gray card stock.

No studio imprint, no handwritten identification on the back, only a faint pencil mark that looked like 1911 and a string of numbers she could not interpret.

The image showed two female figures in a domestic interior.

An older woman, perhaps in her 40s, stood with her hands clasped in front of a cast iron cook stove.

The stove was a majestic range, the kind advertised in cataloges of that era as the pride of any farmhouse kitchen.

To her left and slightly behind, a girl of maybe 14 or 15 stood with her chin raised, wearing a pale work dress and a white apron.

Her hair was pinned back tightly.

Her hands hung at her sides.

Miriam almost filed it under domestic interior, unidentified, but something made her pause.

She leaned closer to her monitor after running the scan.

She zoomed in on the left edge of the frame where a three-legged wooden stool sat against the wall near the door.

At first she thought it was a flaw in the print.

A small bright spot on one of the stools legs.

But when she increased the magnification, the shape resolved into something deliberate.

A brass ring perhaps 2 in in diameter bolted directly into the wood and running through the ring what appeared to be a short length of chain attached to a padlock.

Miriam sat back and removed her glasses.

She had seen a lot in 11 years.

Photographs of company towns where miners lived in squalor.

Images of black families in Nebraska who had homesteaded against impossible odds.

Portraits of children who died before their fth birthdays, posed in their best clothes because their parents could not afford a photograph while they were alive.

But she had never seen furniture designed to restrain a person in a family kitchen.

She looked again at the girl in the uh apron, at her posture, which she had first read as dignity, but which now looked different.

the chin raised not in pride but in defiance.

The hands not relaxed at her sides but pressed flat against her skirt as if she’d been told not to move.

And the distance between her and the older woman, which was not the close affection of a mother and daughter, but the careful gap between warden and ward.

This was not a family portrait.

This was something else.

And Miriam realized she was not going to be able to put it back in the box.

She had trained as a librarian before moving into archival work, spending eight years at a university in Lincoln before the historical society hired her to manage a collection that had been neglected for decades.

Most of her job involved digitization and grant writing.

She gave tours to school groups who wanted to see what Nebraska looked like before highways and irrigation pivots.

She wrote quarterly newsletter articles about centennial farms and pioneer women.

She was not by any definition an investigative journalist or a detective.

But she had learned over the years that photographs lie in specific ways and that understanding those lies required patience and a willingness to follow small details into uncomfortable places.

The stool stayed with her.

She printed a highresolution crop of it and pinned it to the corkboard above her desk.

She started making notes.

The brass ring was manufactured, not improvised.

Someone had purchased it for a purpose.

The chain was short, maybe 18 in, which meant whoever was attached to it could sit on the stool, but not reach the door.

The padlock was a standard design she had seen in cataloges from that period.

This was not a one-time solution.

This was a system.

She returned to the full image and examined the older woman more carefully.

The dress was good quality, not expensive, but respectable.

The kitchen was clean and well equipped.

On the shelf behind the stove, she could make out canning jars and a ceramic picture with a floral pattern.

On the wall, a calendar, though the year was not legible.

This was not a household in poverty.

This was a household with resources, and they had chosen to use those resources to build a restraint into their furniture.

The pencil marks on the back of the card stock nagged at her.

The 1911 was clear enough, but the string of numbers beneath it, which she had initially dismissed as an inventory code, now looked more deliberate.

Seven digits grouped in a pattern that suggested a date and a reference number.

She photographed the back of the card and sent the image to a colleague at the state archives in Lincoln, asking if the format matched any county record system from that era.

The reply came 3 days later.

The numbers match the filing format used by county orphan committees in Nebraska between 1890 and 1925.

The first three digits indicated the year of placement.

The next two indicated the county.

The final two were a case number.

Miriam felt the floor shift slightly beneath her chair.

The girl in the photograph was not a daughter.

She was a placement and the household that received her had documented her arrival with the same notation they might use for livestock or equipment.

She began with the obvious question.

What was an orphan committee and what did it mean to be placed? The answers came quickly, though they were not simple.

Nebraska, like many states in the early 20th century, operated a network of county committees responsible for the welfare of orphaned, abandoned, or delinquent children.

These committees had broad authority to remove children from unsuitable homes and to arrange their placement in families that could provide for them.

The language of the time was charitable.

Children would be given fresh starts and wholesome influences.

Girls in particular would receive domestic training that would prepare them for lives as wives and mothers.

But as Miriam dug into the primary sources, a different picture emerged.

Placement was not adoption.

Families who took in orphan committee children were not required to treat them as their own.

They were instead expected to provide room and board in exchange for labor.

Girls cooked, cleaned, did laundry, cared for younger children, and worked alongside farm wives during harvest.

Boys worked fields, tended livestock, and performed whatever manual labor the household required.

The children received no wages.

Their education was often interrupted or abandoned entirely.

and if they tried to leave before the committee deemed them old enough to be released, they could be forcibly returned.

Miriam found a 1908 report from a state conference on child welfare that described the system in glowing terms.

The placing of dependent children in good family homes is the most natural and effective method of providing for their care and training, the report declared.

The child receives the benefits of family life while the family receives the assistance of an additional pair of hands.

But the same report acknowledged occasional difficulties with placements that did not meet expectations.

A footnote referenced complaints from children who had been overworked or mistreated.

Though the report assured readers that such cases were rare and promptly addressed, Miriam was not reassured.

She reached out to Dr.

Dr.

Helen Voit, a historian at a university in Omaha, whose work focused on child labor and welfare systems in the Great Plains.

Dr.

Voit had spent years studying the orphan trains that brought children from eastern cities to western farms, and she had become increasingly interested in the parallel systems that operated at the county level.

When Miriam described the photograph, Dr.

Voit went quiet for a long moment.

the lock on the stool.

She finally said, “You are certain it is attached to the furniture itself, not just sitting nearby.” Miriam sent her the highresolution scan.

Dr.

Voit studied it and then asked for a day to check her own files.

She called back the following afternoon.

Her voice was careful, as if she were choosing each word deliberately.

“I have seen references to this in testimony,” she said.

“Girls who ran away from placements and were brought back.

Some of them described being locked to furniture as punishment.

Kitchen stools, bed frames, workbenches.

The families called it corrective training.

The idea was that if a girl was physically prevented from leaving, she would eventually accept her situation and stop trying to escape.

Miriam asked if there was documentation, legal records, complaints, investigations.

Almost nothing, Dr.

Voit said.

The children had no standing to complain.

The committees were run by local men who knew the families.

If a girl accused a respectable farm wife of locking her to a stool, who would believe her? And even if someone did believe her, what law had been broken? These were not adopted children.

They were wards of the county placed for labor.

The families had wide discretion in how they enforced discipline.

There was a pause.

Then Dr.

Voit added something that Miriam would remember for a long time.

The genius of the system was that it did not look like slavery.

It looked like charity.

The families were doing a good deed, taking in unfortunate children.

The children were supposed to be grateful.

And if they were not grateful, if they tried to run, then clearly something was wrong with them, not the family.

So the restraints were corrective.

They were helping the child become the person she was supposed to be.

The numbers on the back of the photograph gave Miriam a place to start.

The county code corresponded to Frontier County, a sparssely populated area in southwestern Nebraska.

She contacted the county clerk’s office and asked about historical records from the orphan committee.

The clerk, a woman named Darlene, who had worked in the office for 30 years, said most of the old files had been transferred to the state archives decades ago, but she remembered seeing boxes in the basement that no one had touched in years.

A week later, Miriam drove 4 hours to Stockville.

the Frontier County seat and descended into a concrete basement that smelled of mold and old paper.

Darlene had pulled three boxes labeled orphan committee 19001920 and left them on a folding table under a bare bulb.

The records were fragmentaryary but revealing.

Meeting minutes described placement decisions in brisk business-like language.

The Mueller girl, age 13, placed with the Linquist family, section 14, township 7.

The two Hensley boys, ages 9 and 11, placed with the Reinhardt Farm pending review of their conduct.

There were no photographs in the files, but there were intake forms that recorded the children’s names, ages, physical descriptions, and the circumstances that had brought them to the committee’s attention.

Some were true orphans whose parents had died of illness or accident.

Others had been removed from families deemed unfit due to poverty, alcoholism, or immorality.

A few had been surrendered voluntarily by parents who could not afford another mouth to feed.

Miriam searched for the case number from the photograph.

She found it in a ledger from 1910.

The entry was brief.

Case 112704.

Anna Kowalsski, age 14, parents deceased, influenza, placed with Mrs.

Gertrude Everly, rural Maywood, domestic training.

Anna Kowalsski.

The girl in the photograph had a name.

Miriam kept reading.

The ledger showed quarterly notations for each placement, recording whether the child was satisfactory or in need of adjustment.

Anna’s entries for 1910 and early 1911 were marked satisfactory.

But in the summer of 1911, a different notation appeared.

Returned by Mrs.

Eberly, willful and disobedient, replaced with Mrs.

Eberly after correction.

Miriam stared at the word correction.

She thought of the brass ring bolted to the stool leg.

She thought of a 14-year-old girl alone on a farm miles from anyone who might help her, locked to a piece of furniture because she had tried to leave.

There was one more entry for Anna Kowalsski.

In the fall of 1912, the ledger recorded released at age 16, whereabouts unknown.

The trail went cold after that.

Anna Kowalsski did not appear in the 1920 census under that name.

She did not appear in marriage records for Frontier County or any of the surrounding counties.

Miriam searched newspaper archives for any mention of the Everly family and found only the ordinary notices of farm life, land transactions, church socials, and obituary for Gertude Everly in 1934 that praised her as a devoted wife and mother and a pillar of the Methodist congregation.

But Dr.

Void had suggested another avenue of research.

The children talked to each other, she said.

Even when they could not talk to adults, they found ways to share information.

Sometimes it shows up in unexpected places, church records, school compositions, letters that were never sent, but were kept in drawers for decades.

Miriam contacted the Methodist church in Maywood.

The current pastor, a young man who had arrived only two years earlier, knew nothing about the Everly family.

But he connected her with an older congregant named Ruth Anderson, whose grandmother had been a member of the same congregation in the 1910s.

Ruth was 91 years old and lived in a nursing home in North Platt.

When Miriam explained what she was researching, Ruth was quiet for a long time.

Then she said, “My grandmother told me about the hired girls.

She said some of them were treated well and some of them were not.

She said the ones who were not treated well sometimes ran away and when they were caught things got worse for them.

Miriam asked if her grandmother had ever mentioned a girl named Anna.

No, Ruth said, but she talked about a girl who worked for the Everly.

She did not use her name.

She just called her the one who got away.

Ruth’s grandmother had kept a diary, which Ruth’s family had donated to a local historical society years ago.

Miriam tracked it down and found a single entry from September 1912 that mentioned the Everly household.

The handwriting was cramped and faded, but Miriam could make out most of it.

Mrs.

E came to church alone today.

When I asked after her girl, she said only that the girl had gone and would not be returning.

Her face was hard, and she did not wish to speak further.

Later, I heard from Mrs.

Linquist that the girl had been trouble from the start and that Mrs.

E had done everything possible to correct her.

I do not know what correction means in this case, but I have my suspicions.

I saw the girl once at the general store, and she had a look about her that I have seen in animals who have been penned too long.

I hope she has found somewhere better, but I fear she is only found somewhere else.

Somewhere else? Miriam thought about those words.

A 16-year-old girl with no family, no money, and no legal identity beyond a case number in a county ledger.

Where could she have gone? The answer, when it came, arrived from an unexpected source.

A genealogologist in Colorado named Michael Puit had been researching his own family history when he stumbled across a reference to Anna Kowalsski in a 1914 court record from Denver.

A woman using that name had testified as a witness in a case involving labor conditions at a commercial laundry.

Her testimony described her background as a state girl who had been placed with a farm family in Nebraska before leaving at age 16.

The court record did not include the full transcript of her testimony, but it summarized her statements.

She described being confined to the household and prevented from leaving by physical means.

She had stated that she left Nebraska after gaining her release and traveled to Colorado where she found work in domestic service before moving to the laundry.

She had testified in support of other workers who alleged mistreatment by therrewy’s owners.

Miriam contacted Michael Puit who shared everything he had found.

Anna Kowalsski had married a man named Thomas D’vorak in 1918 and had three children.

She died in 1967 in Pueblo, Colorado.

Her obituary described her as a loving mother and grandmother and mentioned her work with Catholic Charities helping young women in difficult circumstances.

It took Miriam 2 months to locate Anna’s descendants.

A granddaughter named Patricia D’vorak Martinez lived in Albuquerque and initially responded to Miriam’s email with polite suspicion, but when Miriam sent her the photograph, Patricia called within an hour.

“That is my grandmother,” she said.

Her voice was shaking.

I recognized the shape of her face and that look.

She had that look sometimes, even when she was old, like she was watching for something.

Patricia had never known the details of her grandmother’s childhood.

Anna rarely spoke about her years in Nebraska, and when her children asked, she would only say that she had been given away and had to find her own way out.

But Patricia remembered one conversation near the end of her grandmother’s life when Anna had said something that stayed with her.

She told me that people think cruelty looks like monsters in dungeons.

But she said the worst cruelty she ever saw looked like a clean kitchen and a woman in a nice dress.

She said the cruelty was in the ordinary things, the locked doors, the furniture you could not leave.

The way no one ever asked if you were all right because they assumed you must be grateful.

The photograph had been taken, Patricia believed, as a kind of proof.

Proof that Anna was healthy and well cared for.

Proof that the placement was working.

The Everly family would have sent it to the orphan committee as documentation or perhaps kept it to show visitors.

Look at our charitable work.

Look at this girl we have taken in.

But they had not thought to move the stool out of the frame.

Or perhaps they had not thought it mattered.

Perhaps to them the lock and chain were as ordinary as the canning jars in the calendar, just part of the household equipment, just the way things were done.

Miriam brought her findings to the historical society’s board of directors.

In the spring of the following year, she had prepared a detailed report with copies of all the documents she had gathered.

She recommended that the photograph be included in an upcoming exhibition on rural Nebraska life with a full explanation of its context and the system it represented.

The response was not what she had hoped.

The board chair, a retired banker named Harold Swinsson, listened to her presentation with his arms folded.

When she finished, he asked how she could be certain that the brass ring on the stool was used for restraint.

Could it not have been a repair or a hook for hanging tools? Miriam pointed to the chain and the padlock.

She cited Dr.

Voit’s research.

She read the passage from Ruth Anderson’s grandmother’s diary.

Harold shook his head slowly.

This is all very interesting, he said.

But I’m not sure it is appropriate for a family exhibition.

We have school groups coming through.

We have donors who support this institution because they believe in celebrating Nebraska’s heritage.

If we start putting up photographs with stories about children being locked to furniture, what kind of message does that send? Another board member, a woman named Carolyn who owned a chain of farm supply stores, agreed.

I understand your concerns, she said to Miriam.

But there are ways to tell history that bring people together and ways that divide them.

This feels like the second kind.

These were difficult times.

People did what they had to do.

We should not judge them by today’s standards.

Miriam felt something tighten in her chest.

She thought about Anna Kowalsski, 16 years old, walking away from a farm in southwestern Nebraska with nothing but the clothes on her back.

She thought about the system that had placed her there and the respectable people who had locked her to a stool when she tried to leave.

She thought about the way history smooths over the rough edges until everything looks like heritage and nothing looks like harm.

The girl in this photograph was not an ancestor to be celebrated.

Miriam said she was a child who was exploited.

The committee that placed her was supposed to protect her and instead it delivered her to a family that treated her like property.

If we cannot tell that story, then what are we doing here? What is the point of preserving any of this? The room was quiet.

Harold looked at the table.

Carolyn looked at her phone.

Finally, Dr.

Voit who had joined the meeting by video call spoke up.

I want to add something.

She said the orphan committee system in Nebraska placed thousands of children between 1880 and 1930.

We do not know how many of them were mistreated because the records are incomplete and the children had no voice.

But we do know that the system was designed to benefit the families who took them in, not the children themselves.

Every time we tell a sanitized version of that history, we continue the silencing that began when those children were placed.

This photograph is evidence.

It deserves to be seen.

The board voted to table the discussion that they would revisit the matter at their next quarterly meeting.

In the meantime, the photograph would remain in storage.

Miriam did not wait.

She contacted Patricia D’vorak Martinez and asked if she would be willing to share her grandmother’s story publicly.

Patricia agreed.

Together they worked with a journalist at a regional newspaper who was interested in historical investigations.

The article appeared 3 months later with the photograph reproduced in high resolution and the brass ring clearly visible.

The response was immediate and polarizing.

Some readers praised the article for uncovering a hidden injustice.

Others accused the journalist and Miriam of sensationalism of tarnishing the memory of hardworking farm families.

Harold Swinsson issued a statement distancing the historical society from the article and emphasizing that the institution had not endorsed its conclusions.

But something else happened too.

People began to come forward.

Descendants of other placed children who had heard family stories about locked rooms and forbidden departures.

Elderly Nebraskans who remembered whispers about certain households where the help never seemed to leave.

a retired social worker who had studied the orphan committee records in the 1970s and had written a report that was never published because she said no one wanted to hear it.

Dr.

Void compiled the new testimony and cross-referenced it with archival sources.

The pattern was undeniable.

Restraint furniture had been used in placement households across rural Nebraska, Iowa, Kansas, and the Dakotas.

The practice was not universal, but it was not rare either.

It was one tool among many that families used to control children who had been given to them by the state.

The Dawson County Historical Society eventually reversed its position.

The new exhibition, which opened the following year, included the photograph of Anna Kowalsski with a full interpretive panel explaining its context.

Patricia D’vorak Martinez spoke at the opening and read a passage from a letter her grandmother had written to a friend in 1952.

I do not think about Nebraska often, Anna had written.

But sometimes I dream that I am back in that kitchen and I cannot leave and no one is coming to help me.

Then I wake up and I’m in my own house with my own family and I remember that I got out.

I got out because I refused to accept that the lock was permanent.

I think about the girls who did not get out.

I think about them more than I think about myself.

The exhibition drew visitors from across the state and beyond.

Teachers brought classes to see it.

Researchers cited it in academic papers.

A documentary filmmaker began work on a longer project about the orphan committee system.

But Miriam knew that one photograph and one exhibition could not undo a century of silence.

The ledgers in the Frontier County basement contained hundreds of case numbers.

Each number was a child.

Each child had a story.

Most of those stories would never be recovered.

She thought about that often in the years that followed.

How many photographs existed in boxes and albums and historical society collections that contained hidden evidence of exploitation? How many brass rings and locked doors and restrained hands had been captured on film and then filed away under domestic interior unidentified? How many respectable families had posed proudly with the children they were supposed to protect but had instead used as unpaid labor? The camera was a tool of the powerful.

It recorded what they wanted to show.

Prosperity, respectability, the appearance of a well-ordered household.

But sometimes at the edges of the frame, it captured something else.

A detail that did not fit the story.

A stool with a lock.

a girl whose expression said more than the photographer intended.

Photographs are not neutral.

They are arguments made in silver and light.

And sometimes, if you look closely enough, you can see the argument breaking down.

You can see the cracks where the truth leaked through, you can see the evidence that someone somewhere needed you to find.

Anna Kowalsski walked away from a farm in Nebraska in 1912 with nothing.

She died in Colorado in 1967, surrounded by family.

Between those two facts is a life that almost disappeared, swallowed by a system designed to make her invisible.

But the photograph survived, and the photograph told a different story than the one it was meant to tell.

And now, more than a century later, that story has finally been heard.

The next time you see an old photograph of a farmhouse kitchen, look past the smiling faces in the polished stove.

Look at the corners.

Look at the furniture.

Look at the hands of the people who were not supposed to be seen.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load