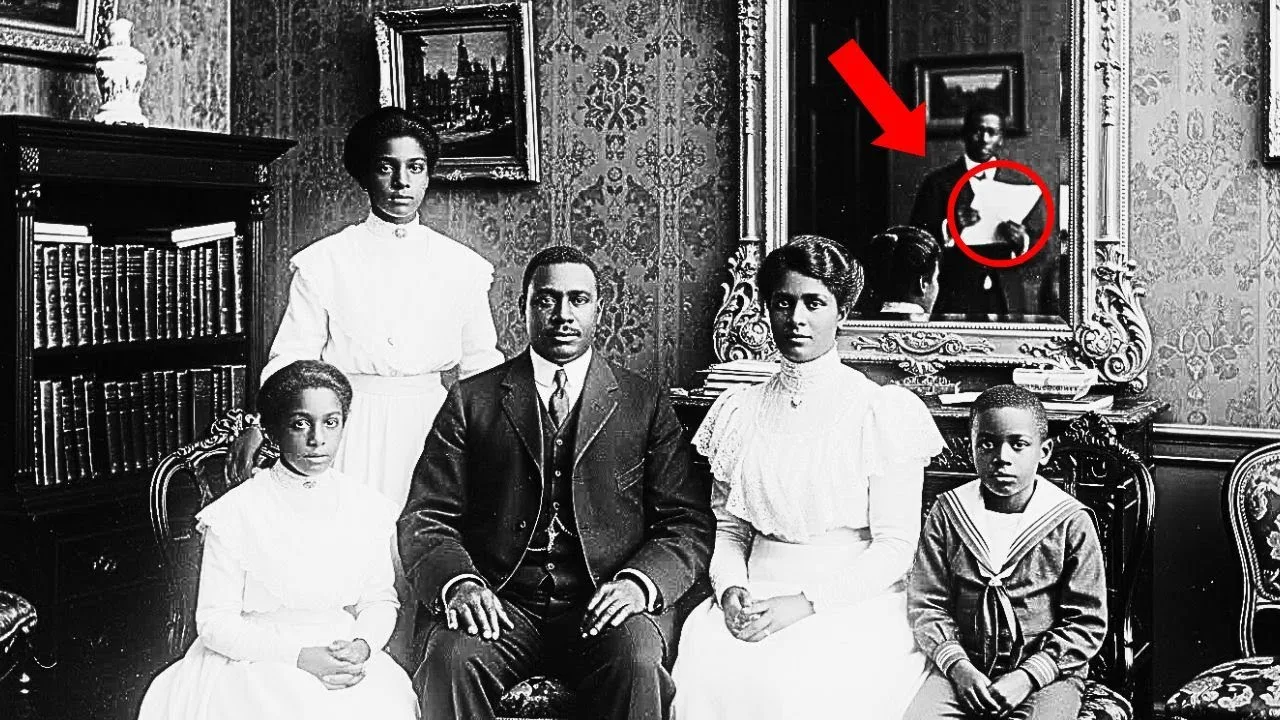

This 1910 photo of a family looks perfect until you spot what’s in the mirror.

The rain drummed against the tall windows of the Boston Heritage Museum as Dr.

Rebecca Hayes carefully lifted another photograph from the cardboard box.

It was late October 2024 and the heating system struggled against the autumn chill.

Rebecca had been cataloging donations for 6 hours straight, her back aching, her eyes tired from examining faded images.

This particular box had arrived three weeks earlier from the estate of Eleanor Whitmore, a local philanthropist who had passed away at 97.

Most of the contents were unremarkable.

Family portraits, vacation snapshots, postcards.

Rebecca was about to close the box when her fingers brushed against a heavy cardboard frame tucked into the bottom corner.

She pulled it out carefully.

The photograph was larger than the others, professionally taken, mounted on thick backing.

The image showed a black family posed in what appeared to be a well-appointed parlor.

Rebecca’s breath caught.

Photographs of prosperous African-American families from this era were exceptionally rare.

The sepia tones had faded only slightly.

In the center sat a dignified man in his 40s wearing a dark suit with a watch chain visible across his vest.

Beside him stood a woman in an elegant high-neck dress with intricate lace details, her hair styled in the Gibson girl fashion.

Three children were arranged around them, two girls in matching white dresses and a boy in a sailor suit.

Rebecca turned on her desk lamp and angled it toward the photograph.

The detail was extraordinary.

She could make out the pattern on the wallpaper, the titles of books on a shelf, even the delicate embroidery on the woman’s collar.

A small label on the back read, “The Harrison family, Boston, 1910.” Rebecca reached for her phone and snapped a quick reference photo, then set the original aside to enter into the museum’s database.

As she typed the information, something nagged at her attention.

She picked up the photograph again, holding it closer to the light.

Behind the family, mounted on the far wall, was an ornate mirror with a gilded frame.

Rebecca squinted at the reflection.

The angle should have shown the photographer and his camera.

Instead, there was something else.

Her pulse quickened.

Rebecca pulled open her desk drawer and retrieved a magnifying glass, positioning it over the mirror’s reflection.

In the dim glass surface, partially obscured by the photographic limitations of 1910, stood another figure, someone who shouldn’t have been there.

Rebecca’s office felt suddenly smaller.

the rain now a distant whisper against her heightened focus.

She adjusted the magnifying glass slowly across the mirror’s surface.

The reflection was small, distorted by angle and the limitations of early photography, but unmistakably present.

A figure stood in the background, clearly separate from where the photographer would have been positioned.

The person appeared to be holding something rectangular against their chest.

Rebecca’s mind raced.

A studio assistant, but why visible in the mirror and not accounted for in the composition? She opened her laptop and launched the museum’s highresolution scanner.

With practiced care, she placed the photograph face down, noting the slight yellowing of the backing, the careful preservation spanning over a century.

The scan took 45 seconds.

Rebecca imported the file and zoomed immediately to the mirror section, enhancing contrast and brightness.

The digital enhancement revealed details invisible to the naked eye.

The figure was definitely a person.

Their posture suggested someone standing very still, deliberately positioned.

The rectangular object looked like a document or folder, edges sharp and formal.

What struck Rebecca most was the placement.

This wasn’t casual.

They were watching the family, observing the photograph being taken.

“Who are you?” Rebecca whispered.

She studied the family again.

The parents expressions now seemed weighted with something beyond period formality.

The mother’s hand rested on one daughter’s shoulder, but her fingers appeared tense, protective.

Rebecca checked the time.

7:30 p.m.

Most staff had left hours ago.

She should go home, start fresh tomorrow.

But the photograph held her.

She opened a browser and typed Harrison Family Boston 1910 African-American.

The search returned general history articles about black families in early 20th century Boston, but nothing specific.

She tried variations.

Prosperous black families, Boston 1910, African-American photographers Boston.

Rebecca learned that Boston’s black community in 1910 was concentrated in the West End and South End.

Despite the city’s abolitionist history, African-Americans still faced significant discrimination.

For a black family to afford such an elegant home and professional photography suggested exceptional circumstances.

The furnishings were expensive.

The mirror alone would have cost considerably.

The books appeared leatherbound, suggesting education.

The children’s clothing was immaculate, tailored.

This was not a struggling family.

This was a family that had achieved something remarkable.

But who was the person in the mirror? And why did their presence feel less like accident and more like warning? Rebecca saved her work and locked the photograph in the museum’s climate controlled storage.

Tomorrow she would visit the archives.

Rebecca arrived at the Massachusetts State Archives at 9:00 sharp, a travel mug of coffee in hand.

She had barely slept, her mind churning through possibilities.

The archives building stood imposing against an overcast sky, its granite facade promising answers buried in centuries of documentation.

Inside, the familiar smell of old paper greeted her.

Thomas Chen, a senior archist and her former classmate, was already sorting through request slips.

Rebecca, he said, looking up.

What’s got you here so early? She showed him the photograph on her phone.

Found it yesterday.

The family is listed as Harrison, Boston, 1910.

I need census records, city directories, property deeds.

Thomas studied the image.

Eyebrows rising.

Beautiful photograph.

Exceptional quality.

He zoomed to the mirror.

Wait, is that someone else? Exactly what I need to find out.

Thomas led her to a terminal and logged into the database.

Let’s start with the 1910 census.

They worked in focused silence, keyboards clicking.

The census records for Boston were extensive, but filtering for black families named Harrison yielded few results.

Here, Thomas said, pointing Harrison James, age 42, head of household, wife Catherine, 38, children Emma, 12, William, 9, Grace, 7.

The ages matched.

Rebecca leaned closer.

Occupation.

Position.

That’s significant.

Very few black doctors in Boston.

Then he scrolled.

Property value $8,500.

That’s substantial.

Address is 47 Beacon Hill.

Rebecca’s pulse quickened.

Beacon Hill was one of Boston’s most prestigious neighborhoods.

For a black family to own property, there would have been extraordinary.

Can you pull property records? Thomas navigated to another database.

Minutes passed.

When results appeared, his expression shifted.

This is odd, he said slowly.

Property purchased 1908 by James Harrison, physician.

But there’s an annotation.

A legal dispute filed in 1911.

The case was sealed by court order.

I can see it existed, but details are restricted.

Rebecca felt a chill.

Sealed records from 1911.

Can we request access? We can try, but it’ll take time.

These old sealed cases usually involve sensitive matters, divorces, financial scandals.

Thomas made a note.

I’ll submit the request today.

Rebecca photographed the census entry.

What about newspapers? There must have been coverage if a black physician owned property on Beacon Hill.

Thomas nodded toward the microfilm section.

The Boston Guardian was the primary African-American newspaper then.

Let me pull the reels from 1908 through 1911.

The microfilm reader hummed as Rebecca scrolled through the Boston Guardian, the leading African-American newspaper of the era.

The additions from 1908 to 1911 were windows into a vibrant but embattled community.

church socials and business achievements alongside reports of discrimination.

Thomas had returned to other duties but showed Rebecca the navigation system.

She worked methodically scanning headlines and society columns for any Harrison mention.

In the June 12th, 1908 edition, she found it.

Local physician purchases Beacon Hill residence.

The article was brief.

Dr.

James Harrison, a respected physician serving the Negro community of Boston’s South End, has purchased the property at 47 Beacon Hill.

Dr.

Harrison, a graduate of Howard University School of Medicine, has practiced in Boston for 15 years.

The purchase has raised some eyebrows among the neighborhood’s established residents, though Dr.

Harrison’s exemplary reputation and professional standing are beyond question.

Raised eyebrows meant likely hostility.

Rebecca continued scrolling.

Over the next two years, society pages occasionally mentioned Katherine Harrison hosting reading groups and charity events at the Beacon Hill home.

Emma Harrison was noted as an accomplished pianist.

William won a citywide essay contest.

The family appeared thriving, actively participating in Boston’s black elite circles.

Then the mentions stopped.

The last reference appeared March 3rd, 1911.

A brief notice that Dr.

Harrison’s medical practice had been temporarily suspended due to unforeseen circumstances.

No explanation given.

Rebecca felt frustration building.

Something had happened between the 1910 photograph and March 1911.

Something significant enough to halt a successful practice and generate sealed court records.

She scrolled forward through 1911.

Then in the November 17th, 1911 edition, something made her breath catch.

In the classified advertisements, information sought.

Family of Dr.

James Harrison seeks information regarding the whereabouts of household members during the period of March June 1911.

Inquiries may be directed to C.

Harrison care of this publication.

Discretion assured household members not family members.

Household members.

The distinction felt important.

Rebecca photographed the screen and continued.

No more advertisements, no follow-up articles.

The Harrison family had vanished from public record.

Thomas returned carrying a folder.

I found something else.

Immigration records from Boston Harbor 1909 to 1911.

He spread documents on the table.

Passenger manifest dated April 14th, 1910.

Passenger name Marie Duchamp.

Age 24.

Origin Porto Prince, Haiti.

Destination: 47, Beacon Hill, Boston.

Purpose, domestic employment.

A Haitian woman arriving to work for the Harrison’s just before the photograph.

Could she be the mirror figure? There’s more, Thomas said quietly.

Border crossing record.

Montreal to Boston, June 1911.

Same name, Marie Duchamp, but this time leaving the United States, returning to Haiti.

The timeline clicked.

Marie arrived April 1910.

The photograph was taken that year.

Dr.

Harrison’s practice suspended March 1911.

The classified seeking household members appeared November 1911.

Marie Duchamp had left.

What happened in those 13 months? Rebecca whispered.

Whatever it was, someone wanted it buried.

Rebecca spent the next week following every thread, but the trail had gone cold.

The sealed court records remained inaccessible.

No death certificates existed for the Harrisons in Massachusetts during the 1910s, meaning they had either moved or their records were lost.

Property records showed 47 Beacon Hills sold in 1912 with no forwarding address.

The family had been erased.

Then on a gray Friday afternoon, Rebecca’s phone rang, an unfamiliar Boston number.

Dr.

Hayes, this is Patricia Armstrong.

I’m a genealogologist with the African-American Heritage Society.

A colleague mentioned you were researching the Harrison family from Beacon Hill.

I think I can help.

Rebecca straightened.

Yes, absolutely.

What do you know? It’s not what I know, it’s who I know.

My grandmother is 91.

Her mother was Emma Harrison.

The daughter in your photograph? Rebecca could barely breathe.

Emma Harrison is your great-grandmother.

Was.

She passed in 1998, but my grandmother Dorothy is very much alive and living in Roxbury.

She’s been wanting to talk about her mother’s story for years, but didn’t know who to trust.

When she heard a museum curator was asking questions, she told me to reach out.

They arranged to meet the following afternoon at Dorothy’s Roxbury home.

Rebecca barely slept that night.

Saturday arrived cold and bright.

Rebecca drove through Roxbury’s treeline streets until she reached Dorothy Armstrong’s address, a tidy rowhouse with a well-maintained garden showing Autumn’s last blooms.

Patricia met her at the door, warm-eyed, but cautious.

She’s in the living room.

Please understand, this story has caused pain for over a century.

My grandmother is sharing it because she believes the truth deserves to be known.

Rebecca followed her inside.

Dorothy Armstrong sat in a wing backed chair by the window, afternoon sunlight illuminating her silver hair.

Despite her age, her eyes were sharp.

Photographs covered the walls.

Family portraits spanning generations.

Rebecca recognized elements from the 1910 photograph and Dorothy’s features.

The same strong jawline, the same intelligent gaze.

Dr.

Hayes, Dorothy said, her voice steady.

Patricia tells me you found my mother’s photograph, the one with the mirror.

Rebecca sat across from her.

Yes, ma’am.

I’ve been trying to understand what happened to your family.

Dorothy’s hands tightened on her chair arms.

What happened to my family is what happened to many black families then, Dr.

Hayes.

We dared to succeed and we paid the price.

She paused.

But our story has complications.

You saw the figure in the mirror? Yes.

I believe it was Marie Duchamp, a woman from Haiti who worked for your family.

Dorothy’s eyebrows rose.

You’ve done your research.

Yes, that was Marie.

But she wasn’t just a household worker.

She was family.

Dorothy reached for a photograph album on the side table.

Her movements deliberate.

She opened it to a marked page and passed it to Rebecca.

The image showed a young woman with delicate features and intelligent eyes, her hair styled in early 1900s fashion.

Even in faded sepia, her beauty was evident.

Marie Duchamp, Dorothy said softly.

My grandfather James had a brother named Samuel.

Samuel was a merchant marine who traveled throughout the Caribbean.

In 1908, he met and fell in love with Marie in Porto Prince.

Rebecca looked up from the photograph.

Samuel wanted to marry her, but there were complications.

Laws in the United States were deeply hostile to interracial relationships, more so to immigration from Haiti.

Political tensions were building.

The United States would occupy Haiti in 1915, but tensions already existed.

Bringing a Haitian woman to Boston as a wife would have drawn dangerous attention.

So Samuel brought her as a domestic worker.

Yes.

My grandfather James’ idea.

He petitioned to employ a household worker from Haiti.

Used his standing as a physician to vouch for it.

Maria arrived April 1910, but she and Samuel were already married in a ceremony at Porto Prince with no legal standing in the United States.

They kept it secret.

To the world, Marie was simply the housekeeper.

Dorothy’s expression troubled.

But Samuel was often at sea for months.

Marie lived in that Beacon Hill house with my grandfather’s family, helping with children, managing the household.

My mother, Emma, adored her.

Marie taught her French, told her stories about Haiti, braided her hair evenings.

“The photograph,” Rebecca said carefully.

Marie is in the mirror, but not the formal portrait.

“Why?” “Because she couldn’t be,” Dorothy said, voice heavy with old pain.

When the photographer came, Marie wanted to be part of it.

Samuel was home that month, rare for him.

But my grandfather James refused.

He said it was too dangerous that if anyone saw a photograph showing Maria’s family, questions would be asked.

Their entire arrangement could collapse.

Rebecca felt a knot forming, so she stood behind the camera watching.

Exactly.

My mother said Marie stood there the entire time, positioning the family, adjusting their clothes.

She was heartbroken at being excluded, but understood the risk.

Samuel argued with James, but James wouldn’t budge.

Dorothy’s fingers traced the album edge.

What James didn’t know was that the mirror would capture Marie’s reflection.

The photographer didn’t notice or didn’t care.

When the family received the finished photograph, there she was, a ghost in the background of her own family’s portrait.

Rebecca studied the original on her phone, zooming to Marie’s reflection.

Understanding the context, she could see the object more clearly.

What is she holding? Dorothy smiled sadly.

Her marriage certificate from Haiti.

Samuel had given it to her in a leather folder.

My mother said Marie kept it always.

proof of who she really was, even though that proof meant nothing in American law.

What happened to her? Dorothy’s expression hardened.

The neighbors on Beacon Hill were already suspicious.

A prosperous black physician living among them was barely tolerable.

They watched that house constantly.

In early 1911, someone reported to immigration authorities that the Harrison household was harboring an illegal immigrant under false pretenses.

Dorothy’s hands trembled slightly as she continued, “They did more than investigate.

They raided the house in March 1911.

My grandfather was arrested for immigration fraud.

His medical license was suspended.

The family’s reputation was destroyed overnight.

Uh Rebecca leaned forward, the weight of the story pressing down.

And Marie deported back to Haiti within two weeks.

Samuel tried to fight it, hired lawyers, filed appeals.

Nothing worked.

She was gone.

Dorothy’s voice wavered, but held firm.

The classified advertisement in the Guardian, the family seeking information about household members.

They weren’t looking for Marie.

They already knew where she’d been sent.

They were looking for witnesses who could testify on their behalf, anyone who could help fight the charges.

Did Samuel ever see her again? Dorothy shook her head.

He died in 1913 in a shipping accident off the Cuban coast.

My grandmother, Catherine, always believed he’d been trying to find a way to reach Haiti to bring Marie back somehow, but records show he was just working his regular route.

She paused.

After his death, the family gave up the fight.

The charges against my grandfather James were eventually dropped due to lack of evidence, but his reputation never recovered.

They sold the house and moved to New York in 1912.

Rebecca sat back, processing everything.

Do you know what happened to Marie after she was deported? We never knew.

My mother carried guilt her whole life about it.

She was only 12.

There was nothing she could have done, but she felt it nonetheless.

Before she died, she made me promise that if I ever learned what happened to Marie, I would make sure her story was told properly.

Rebecca pulled out her laptop.

May I show you something? She opened the enhanced digital version of the photograph, zooming to the mirror where Marie’s reflection stood, holding the marriage certificate.

The enhancement made Marie’s features clearer, her posture more defined.

Dorothy stared at the screen, tears forming.

I never saw her this clearly before.

My mother described her as beautiful, kind, patient with children.

Now I can see what she meant.

With your permission, Rebecca said carefully.

I’d like to try to find out what happened to Marie after 1911.

There might be records in Haiti, immigration documents, something that could give us the rest of her story.

Dorothy nodded.

Please.

My mother would want that.

Rebecca spent the next two weeks reaching out to contacts, historians specializing in Haitian immigration, genealogologists familiar with Caribbean records, archavists in Porto Prince.

The responses were slow, many leads turning into dead ends.

Then three weeks after meeting Dorothy, Rebecca received an email that changed everything.

It was from Dr.

Jean Michelle Lauron, a historian at the University of Haiti.

He had found records of Marie Duchamp’s return to Porto Prince in June 1911.

But there was more.

Marie had been pregnant when she was deported.

She had given birth to Samuel’s son in February 1912, 7 months after being forced to leave Boston.

Samuel Harrison had died, never knowing he’d fathered a child.

Rebecca stared at the birth certificate Dr.

Lauron had attached.

The baby’s name Samuel Harrison Duchamp.

Marie had raised their son alone in Haiti.

And according to Dr.

Lauron’s research, she had returned to her profession as a teacher, working at the Eco National in Porto Prince for over 30 years.

She had died in 1947 at 61, and her descendants, Samuel’s descendants, were still living in Porto Prince.

Rebecca’s hands shook as she dialed Dorothy’s number.

When Patricia answered, Rebecca asked if she could come over immediately.

An hour later, she sat in Dorothy’s living room again, laptop open, showing them Dr.

Lauron’s findings.

Dorothy stared at the birth certificate, her face a mixture of shock and wonder.

Marie had a baby.

Samuel’s baby.

A son, Rebecca said gently, named after his father.

Dr.

Laurent found that he became a physician himself, studied in France, returned to Haiti to practice.

He married, had children.

Marie’s line continued.

Patricia leaned over her grandmother’s shoulder, reading the documents.

We have family in Haiti.

Living family descended from Samuel.

Dr.

Lauron has already made contact with them.

Rebecca said Marie’s great-grandson is a history professor at the University of Haiti.

His name is Claude Duchamp.

He knows about Marie’s time in Boston, about her marriage to Samuel, but he never had documentation from the American side.

He’d like to speak with you if you’re willing.

Dorothy looked at Rebecca, then at Patricia.

Over a century, she whispered.

Over a century, and Samuel’s line survived.

Marie raised his son, kept his memory alive.

Rebecca set up the video call for the following Saturday.

When the day arrived, she returned to Dorothy’s house to help facilitate the conversation.

The laptop was positioned so Dorothy could sit comfortably, Patricia beside her.

When Claude Ducham appeared on screen, the resemblance to the Harrison family photograph was unmistakable.

He had the same strong features, the same intelligent eyes.

He was in his 40s, sitting in an office lined with books.

“Mrs.

Armstrong,” he said in lightly accented English, his voice thick with emotion.

“This is extraordinary.

My family has known pieces of this story for generations, but we never had documentation from the American side.” Rebecca showed him the 1910 photograph, zooming to Marie’s reflection.

Claude leaned closer to his screen, his expression shifting from curiosity to deep emotion.

“That’s her,” he whispered.

“I’ve seen paintings, family sketches, but never a photograph.

And she’s holding something.

What is that?” her marriage certificate, Rebecca said gently, from her wedding to Samuel and Portorto Prince.

Claude disappeared briefly from screen and returned holding a leather folder, aged and worn but carefully preserved.

He opened it to show a certificate written in French.

The paper yellowed but text still legible.

This certificate was proof of who she was when everything else was taken, Claude said.

Proof that she’d been loved, that she’d been married, that she belonged to someone.

The American government didn’t recognize it, but she never stopped believing in its truth.

Dorothy wiped tears from her cheeks.

Your great-grandfather Samuel never knew about his son.

He died in 1913.

We know Marie told her son stories about his father, that he was brave, that he worked at sea, that he tried to build a life for them in America, but the world wouldn’t allow it.

My grandfather Samuel grew up knowing he was named after a father he never met.

But he was proud of that name.

He became a doctor like his uncle James, carrying on the family tradition, even though he’d never met the American side of his family.

Gil.

The conversation continued for over an hour.

Both families sharing stories, comparing photographs, discovering connections across generations.

Dorothy learned that Emma had become a music teacher in New York just as Marie had been a teacher in Haiti.

Claude learned that his grandfather Samuel had inherited not only his father’s name, but his grandfather’s calling to medicine.

Before ending the call, Rebecca made a proposal.

I’d like to create an exhibition at the museum telling this complete story.

Would both families be willing to participate? Claude smiled.

We’ll be there.

Marie waited over 30 years, hoping to reunite with the Harrison’s.

I think we can manage a plane flight to Boston.

The exhibition opened on April 14th, 2025, exactly 115 years after Marie Duchamp had arrived at Boston Harbor.

Rebecca had worked tirelessly for 3 months, collaborating with both families to create something that honored the truth without sensationalizing the pain.

The museum’s main gallery had been transformed.

The 1910 photograph hung at the entrance, enlarged to 4 ft wide, with the mirror section highlighted and enhanced.

A placer beside it read, “Look closer.

The story of Marie Duchamp and the Harrison family.” Rebecca stood near the entrance, watching visitors enter.

Some walked past casually at first, then stopped when they noticed the figure in the mirror.

She watched their faces change as they read the accompanying text, as they began to understand what they were seeing.

The exhibition was organized chronologically, telling the story through documents, photographs, and personal artifacts both families had contributed.

The immigration manifest showing Marie’s arrival, the property deed amendment that had triggered the investigation, the deportation order, the letters Marie had written from Haiti never answered, the birth certificate of her son.

But there were also objects showing the fullness of their lives.

Marie’s teaching certificate from 1914, a photograph of her with students in the 1930s, all looking at her with clear affection.

A medical diploma belonging to Dr.

Samuel Harrison Duchamp from the Sorbon in 1935.

A letter from Emma to her children in the 1960s, mentioning Marie and expressing regret they had lost contact.

Dorothy had brought a box of her mother’s belongings.

Among them was a small pressed flower, dried and fragile, tucked inside an envelope addressed to Emma and Marie’s handwriting, but never mailed.

Inside a note in French, for Emma with love.

Remember the garden at Beacon Hill.

Dorothy had cried when she saw it.

My mother kept flowers pressed in books her whole life.

I never knew why.

Now I understand.

The centerpiece was a video installation showing interviews with both families.

Dorothy spoke about her mother’s memories of Marie.

Claude spoke about growing up with stories of his great-grandmother’s time in America.

Patricia and Claude’s daughter, both genealogologists, discussed the research that had brought the families back together.

At the end, in a quiet corner designed for reflection, hung a new portrait.

A digitally created composite showing Marie Duchamp standing with the Harrison family.

No longer hidden in the mirror, but visible, present, acknowledged.

It was historical imagination, giving her the place in the family photograph she had been denied in 1910.

The opening reception was crowded.

Local news had covered the story.

People came from across Boston.

historians, genealogologists, members of the African-American community, descendants of Haitian immigrants, simply curious visitors drawn by the mystery.

But the moment Rebecca would remember most came when Claude arrived with his family from Haiti.

He walked through the entrance and stopped in front of the large photograph, staring at his great-grandmother’s reflection.

Dorothy, using a cane, but moving with determination, approached from the other side.

They met in front of the photograph, these two descendants of a love that had been forbidden, a family that had been torn apart, a story that had been buried for over a century.

Claude held out his hand to Dorothy.

She took it and pulled him into an embrace.

“Welcome home,” Dorothy said softly.

“Your great-grandmother came to the city with hope.

I’m glad you could come back with pride.” The exhibition ran for 6 months and became the museum’s most visited show in a decade.

People came from across the country, many bringing their own family photographs, their own stories of separation and loss, hoping to find similar hidden truths in the images they had inherited.

Rebecca gave dozens of tours, each time watching visitors faces as they moved through the story.

She saw recognition in the eyes of immigrants who understood what it meant to have your identity questioned.

She saw pain in the faces of those who had experienced family separation.

She saw hope in young people who realized that even buried stories could eventually be uncovered.

The photograph itself, the original 1910 portrait, became something different than what it had been when Rebecca first found it.

It was no longer just a beautiful image of a prosperous black family.

It was evidence of love that had defied legal boundaries, of a woman who had been deliberately excluded, but whose presence had been captured anyway by the mirror’s honest reflection.

Dorothy visited the exhibition 17 times before it closed.

Each time she spent the longest time in front of the letters Marie had written from Haiti.

Letters that had never reached their intended recipients, but now finally had been read by the family they were meant for.

Claude returned to Boston twice more during the exhibition’s run, bringing different family members each time.

On his final visit, he brought Marie’s original marriage certificate, the same one she had held in the photograph, and donated it to the museum’s permanent collection.

“This belongs here now,” he said to Rebecca, as they stood in the gallery after hours.

Marie held on to it because it was proof of her truth when no one else would acknowledge it.

Now it can be proof for everyone who needs to know that their stories matter, even when the law tries to erase them.

Rebecca accepted the certificate with reverence, understanding the weight of what Claude was entrusting to the museum.

The leather folder was worn smooth by Marie’s hands by decades of being held, treasured, protected.

Inside the certificate’s French text was still clear.

Marie Duchamp and Samuel Harrison married in Porto Prince, August 15th, 1908.

A marriage that had been real even when it wasn’t recognized.

A love that had endured even when it was punished.

After the exhibition closed, Rebecca worked with both families to create a permanent digital archive, ensuring that the documents, photographs, and interviews would be accessible to researchers, educators, and anyone interested in the complicated history of immigration, race, and family in America.

She kept the 1910 photograph on her office wall, not the original, which was now in the museum’s climate controlled storage, but a highquality reproduction.

Sometimes when she worked late into the evening, she would look up at it and think about Marie Duchamp standing behind that camera, watching the family she loved pose for a portrait that excluded her.

The mirror had told the truth that the photograph’s composition had tried to hide.

Marie had been there.

She had been part of that family.

And now, over a century later, everyone who looked at the image would know it.

The story didn’t end with tragedy, Rebecca thought.

It ended with recognition with Dorothy and Claude standing together in front of their family’s shared history.

With Marie’s teaching certificate displayed beside her son’s medical diploma, with proof that love doesn’t disappear simply because the law says it shouldn’t exist.

Rebecca thought about what Claude had said during one of their conversations.

My great-grandmother always told her son that the truth has a way of surfacing, even when it’s been buried deep.

She believed that someday her story would be known.

Marie had been right.

It had taken 115 years, a chance discovery in a donation box, a figure barely visible in a mirror’s reflection.

But the truth had surfaced.

And in surfacing, it had reunited families, corrected historical records, and given Marie Duchamp her rightful place.

Not hidden in the background, but standing clearly in the light.

Her story finally completely

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load