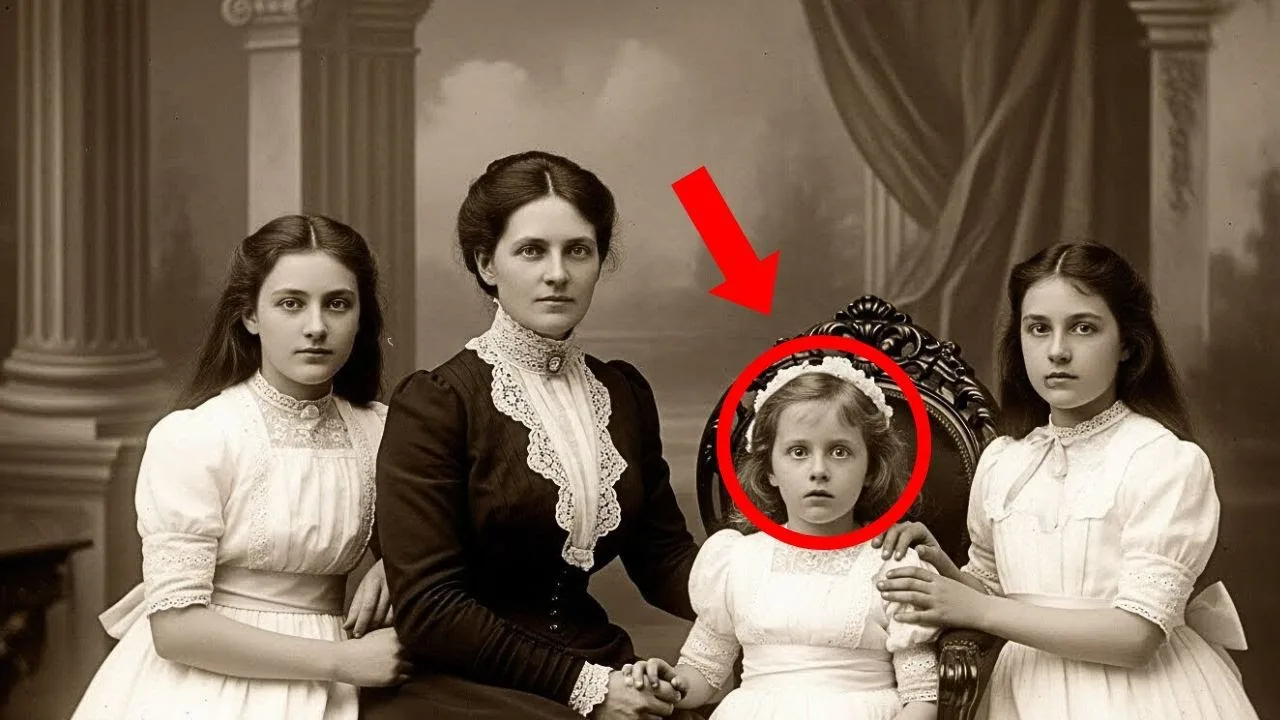

This 1908 photo of a mother and daughters looks peaceful until you notice who isn’t looking at the camera.

Dr.Helen Morrison had dedicated 20 years to studying Victorian and Edwwardian family photography, but the image that appeared on her screen that October morning in 2024 made her pause mid sip of coffee.

She was cataloging recently digitized photographs from the Boston Historical Society’s archives, thousands of images that had spent decades in storage.

The photograph was labeled simply family portrait, Boston Studio, 1908.

At first glance, it seemed entirely ordinary.

A formal family portrait typical of the era.

A mother in her mid-30s sat in an ornate chair wearing a high-neck dark dress with delicate lace at the collar.

Her hair was styled in the Gibson girl fashion popular at the time.

Three daughters surrounded her, all wearing pristine white dresses with elaborate ribbons and bows.

The youngest appeared to be about 6 years old, the middle daughter perhaps nine, and the eldest around 12.

The studio backdrop showed painted columns and draped fabric, standard elements of formal photography from that period.

Everything appeared peaceful, prosperous, proper.

But something felt wrong.

Helen leaned closer to her monitor, enlarging the image.

She studied each face carefully.

The mother stared directly at the camera with a composed, almost rigid expression.

The two older daughters also faced the camera, their smiles slight and controlled.

The youngest daughter was different.

While her mother and sisters looked forward, the small girl’s face was turned sharply to the left.

Her eyes wide and fixed on something outside the frame.

Her expression was not one of childish distraction or boredom.

It was fear.

Pure unmistakable fear.

Helen felt a chill run down her spine.

She had seen thousands of old photographs, including many stiff, uncomfortable family portraits where children squirmed or looked away.

But this was different.

The intensity in the child’s eyes, the tension visible even through the faded sepia tones spoke of something darker.

She zoomed in further, examining other details.

The mother’s right hand rested on the youngest daughter’s shoulder, but as Helen looked closer, she could see the fingers were pressed deeply into the fabric of the white dress, the pressure creating visible wrinkles in the cloth.

Helen saved the image to her research folder and marked it for further investigation.

She had learned to trust her instincts about photographs, and every instinct was telling her this image held secrets that needed to be uncovered.

Helen spent the next morning searching for any documentation related to the photograph.

The Boston Historical Society’s records were extensive, but often incomplete, with gaps where fires, floods, or simple neglect had destroyed documents over the decades.

She started with photography studio records from 1908.

Boston had dozens of studios operating during that period, but the painted backdrop in the image looked familiar.

She cross-referenced it with known studio signatures and identified it as the work of Whitfield and Sons, a prominent studio on Tmont Street.

The historical society had acquired a partial collection of Whitfield Studio records in 1967.

Helen requested the boxes which arrived at her desk that afternoon.

Three containers filled with ledgers, correspondents, and loose papers.

She opened the first ledger, running her finger down entries from 1908.

The handwriting was elegant but fading.

Each entry listing the date, client name, type of portrait, and payment received.

On March 14th, 1908, she found it.

Mrs.

Catherine Harrison and daughters family portrait sitting.

Full payment received.

Harrison.

Helen now had a surname.

She photographed the page and continued searching through the records, hoping for more details.

In a folder of correspondence, she found something unexpected.

A letter dated March 20th, 1908, written in a different hand than the ledger entries.

Mr.

Whitfield, I must speak with you regarding the Harrison family portrait from last week.

There are concerns about the sitting that I feel obligated to share.

Please call upon me at your earliest convenience.

Jay Foster, assistant photographer.

The letter was papercliped to a brief response.

Matter discussed and resolved.

No further action taken.

E.

Whitfield.

What concerns? What had the assistant photographer noticed and why was no action taken? Helen’s investigation was shifting from simple historical curiosity to something more urgent.

She needed to find out who the Harrison family was and what had happened in that studio on March 14th, 1908.

She turned to census records in city directories, searching for Katherine Harrison with three daughters living in Boston in 1908.

The search returned several possibilities, but one stood out.

Katherine Harrison, age 34, residing at 287 Beacon Street, one of Boston’s most prestigious addresses.

The household listing included her husband, Dr.

William Harrison, physician, age 42.

Helen’s research into the Harrison family revealed a picture of upper class Boston respectability.

Dr.

William Harrison had graduated from Harvard Medical School in 1889 and established a successful practice treating Boston’s wealthy elite.

He specialized in nervous disorders, particularly in women, a common and lucrative field at the time.

Contemporary newspaper accounts painted him as a pillar of the community.

He served on the board of Massachusetts General Hospital, contributed to medical journals, and was frequently mentioned in society pages attending charity gallas and cultural events.

Catherine Harrison, nay Catherine Lel, came from an old Boston family with significant wealth.

She had married William in 1895 when she was 21 and he was 29.

Their three daughters were born in succession.

Margaret in 1896, Dorothy in 1899, and Clara in 1902.

On paper, they were the ideal American family of the progressive era.

Successful, cultured, charitable.

But Helen had learned that Victorian and Edwardian families often hid darkness behind their public facades.

The era’s obsession with respectability meant that family problems, especially violence or abuse, were systematically concealed.

She searched for any newspaper mentions of the Harrison’s Beyond Society pages.

Most articles were benign, announcements of births, descriptions of parties hosted at their Beacon Street home, lists of charitable donations.

Then she found something unusual.

A small article from the Boston Globe dated April 1907, nearly a year before the photograph was taken.

Dr.

William Harrison was called to testify yesterday in the case of Mrs.

Helen Bradshaw, who stands accused of attempting to harm herself.

Dr.

Harrison, who had been treating Mrs.

Bradshaw for nervous hysteria, stated that such conditions in women often lead to irrational and dangerous behavior.

He recommended continued institutional care.

Helen felt her stomach tighten.

The language was typical of the era’s medical establishment, which often diagnosed women with hysteria, and used it to justify controlling or institutionalizing them.

But reading it now, knowing what she suspected about Harrison’s own family, the article took on a sinister quality.

She found more articles mentioning Harrison’s testimony in similar cases, always involving women, always recommending institutional treatment, always emphasizing women’s irrationality and danger to themselves.

A man who professionally diagnosed women as unstable and hysterical.

A man whose own daughter stared in terror at something outside the camera’s frame while her mother’s hand gripped her shoulder with visible force.

Helen’s research was revealing a pattern, but she needed more evidence.

She needed to know what happened to the Harrison family after that photograph was taken.

Helen couldn’t stop thinking about Jay Foster, the assistant photographer who had written that concerned letter to Mr.

Whitfield.

What had Foster seen during the Harrison family sitting that warranted reaching out afterward? She returned to the studio records, searching for any mention of Foster.

She found employment records showing Joseph Foster had worked at Whitfield and Sons from 1906 to 1909.

After 1909, the trail went cold.

Helen expanded her search, looking through Boston city directories for Joseph Foster.

She found him listed as living in the North End through 1912, working at various photography studios.

Then his name appeared in ship manifests.

He had immigrated to Canada in 1913.

The chances of finding any trace of Foster over a century later seemed impossible, but Helen had learned that determined researchers often got lucky.

She posted a query on genealogy forums describing what she knew about Joseph Foster and asking if anyone had information about descendants.

3 days later, she received an email from a woman named Patricia Ellis in Toronto.

Joseph Foster was my greatgrandfather.

I have some of his papers and photographs.

Why are you looking for information about him? Helen’s hands trembled as she typed her response, explaining the Harrison family photograph and the mysterious letter.

Patricia replied within hours.

I think I have something you need to see.

They arranged a video call for the following evening.

When Patricia’s face appeared on screen, Helen could see she was holding a small leather journal.

My great-grandfather kept detailed diaries, Patricia explained.

I’ve been slowly transcribing them for our family history project.

When I got your message, I searched for mentions of the name Harrison.

She opened the journal to a marked page.

This entry is from March 14th, 1908, the date of the photography session.

Patricia began reading aloud.

Today, I witnessed something that troubles me deeply.

A family came for a portrait.

mother and three daughters.

The father arrived with them but remained in the studio during the sitting standing behind Mr.

E.

Whitfield.

The youngest child kept looking at her father with such fear in her eyes that I could barely focus on preparing the equipment.

When I suggested the father wait in the reception area, he refused, saying he needed to ensure his family presented themselves properly.

The mother’s hand shook the entire time.

The little one never looked at the camera once.

Patricia paused, then continued.

When they left, I found a small note tucked behind the curtain where the mother had been standing.

It read simply, “Help us.” Helen sat motionless, staring at the screen as Patricia’s words settled over her.

“A note?” Catherine Harrison had left a note, a desperate plea hidden where only the studio staff might find it.

“What happened to the note?” Helen asked, her voice barely above a whisper.

Patricia turned the journal page.

My great-grandfather wrote that he took the note to Mr.

Whitfield immediately, but Whitfield refused to get involved.

He said, “We are photographers, not social workers.

Dr.

Harrison is a respected physician.

His wife is probably suffering from nervous hysteria, which he would know better than we would.” “So Whitfield did nothing,” Helen said, feeling anger rise in her chest.

Not exactly nothing, Patricia corrected.

She held up a small envelope that had been pressed between the journal pages.

My great-grandfather kept the note, and he did try to help in his own way.

Patricia carefully opened the envelope and held up a yellowed slip of paper to the camera.

Helen could make out the handwriting, shaky but clear.

Help us.

There’s more, Patricia said, flipping ahead in the journal.

A week after the sitting, my great-grandfather went to the Harrison house.

He pretended to be delivering additional copies of the photograph.

He hoped to speak with Mrs.

Harrison privately.

Patricia read the entry.

March 21st, 1908.

I went to the Beacon Street address today.

A housekeeper answered and said Mrs.

Harrison was indisposed and could not receive visitors.

But as I turned to leave, I saw a face in the upper window.

one of the daughters, the eldest.

I think she was watching me, and even from the street, I could see bruising on her face.

Helen closed her eyes, the full picture becoming clearer and more horrifying.

“This wasn’t just about the youngest daughter’s fear.

The entire family was living in terror.

“Did your great-grandfather report what he saw?” Helen asked.

“He tried,” Patricia said sadly.

He went to the police the next day.

But when he explained the situation that Dr.

Harrison might be abusing his family, the officer laughed at him, told him that Dr.

Harrison was a respected man who would never do such things, and that women and children were the doctor’s responsibility to manage as he saw fit.

Before women had the right to vote, before domestic violence was recognized as a crime, before children had legal protections, the Harrison women and girls had been legally trapped.

“Is there anything else in the journal?” Helen asked.

Patricia nodded slowly.

“One more entry about the Harrisons from June 1908.

But I should warn you, it’s not easy to read.” Patricia found the June entry and began reading, her voice heavy with emotion.

June 7th, 1908.

I learned today of a terrible incident involving the Harrison family.

Mrs.

Katherine Harrison attempted to leave her husband, taking the three daughters with her.

She had somehow managed to secure train tickets to New York, planning to seek refuge with her sister.

Helen leaned closer to her screen, her heart pounding.

They were stopped at the train station.

Patricia continued, “Dr.

Harrison had discovered their plan and arrived with a police officer.

He claimed his wife was suffering from a severe nervous breakdown and was attempting to kidnap his children during a hysterical episode.

The officer believed him without question.

They were all taken back to the Beacon Street House.

Patricia’s voice caught.

My great-grandfather wrote, “I saw Mrs.

Harrison being led from the station.

Her face was blank, empty of all expression, as if her spirit had been extinguished.” The youngest daughter was crying.

The doctor was smiling.

Helen felt sick.

Catherine had tried to escape, had gathered the courage to take her daughters and run.

And the very systems that should have protected them had forced them back into danger.

Did Joseph Foster try to help again? Helen asked.

He wanted to, Patricia said.

But look what he wrote next.

I went again to the police, bringing the note and my testimony.

This time, two officers came to question me.

They asked how I knew Mrs.

Harrison was being abused and not simply suffering from hysteria as her husband claimed.

They suggested I was overstepping boundaries and warned me that making false accusations against a prominent doctor could result in legal action against me.

I am ashamed to admit I became frightened for my own safety and position.

Helen understood.

Joseph Foster had been a young man, an assistant photographer with no social standing, going up against one of Boston’s medical elite.

“The entire structure of society had been designed to protect men like William Harrison and silence anyone who challenged them.” “Is that the last mention of them?” Helen asked in his journal.

“Yes,” Patricia said.

“But there’s one more thing.” She held up a newspaper clipping carefully preserved in a plastic sleeve.

This is from July 15th, 1908.

My great-grandfather kept it tucked in the back of his journal.

The headline read, “Prominent Boston physician’s wife institutionalized for nervous breakdown.” Patricia read the article.

“Mrs.

Katherine Harrison, wife of the esteemed Dr.

William Harrison, has been admitted to Danver State Hospital for treatment of severe nervous hysteria and melancholia.

Dr.

Harrison released a statement expressing his deep sorrow at his wife’s condition and his hope that modern medical treatment will restore her to health.

The couple’s three daughters are being cared for by family members during their mother’s treatment.

Helen’s hands clenched into fists.

He had her committed.

Legally, he had every right.

Patricia said quietly.

Husbands could commit wives to asylums with just their signature.

No second opinion required.

No way for the woman to refuse.

Helen knew she had to trace what happened to Katherine Harrison after her commitment to Denver State Hospital.

The facility, which operated from 1878 to 1992, had been notorious for overcrowding and inhumane conditions, though it was considered progressive when first opened.

She contacted the Massachusetts State Archives, which held patient records from closed institutions.

After explaining her research and filling out privacy waiver forms, the records were old enough to be accessible under public records laws, she received digital files 3 weeks later.

Katherine Harrison’s admission file was heartbreaking in its clinical detachment.

Admitted July 12th, 1908, age 34.

Diagnosis: Hysteria, severe melancholia, delusions of persecution.

The admitting physicians notes, clearly based on information provided by William Harrison, described Catherine as increasingly irrational, making wild accusations against her husband, attempting to abscond with children, danger to herself, and potentially to others.

There was no record of Catherine being interviewed independently or examined by a physician other than her husband.

The treatment notes made Helen’s stomach turn.

Catherine was subjected to the standard cures of the era.

Ice baths, prolonged bed rest, forced feeding when she refused meals, and isolation when she was deemed agitated, which appeared to be any time she asked about her daughters.

One nurse’s note from August 1908 stood out.

Patient continues to insist she is not ill, that she was forced here unjustly.

She begs daily to see her children.

She has given up eating.

physician has ordered feeding tube.

Catherine was being punished for telling the truth.

Helen found more notes documenting Catherine’s deterioration.

By October 1908, she had been transferred to a more secure ward.

By January 1909, the notes described her as withdrawn, non-communicative, resigned to treatment.

They had broken her spirit.

But then Helen found something unexpected.

A note from March 1909 written by a different nurse.

Patient received visitor today.

Her sister Miss Alice Lel.

Patient became animated for first time in months.

After visit, patient requested writing materials.

Request denied by attending physician on orders from Dr.

Harrison who states that writing materials might be used for self harm.

Catherine’s sister had found her and William Harrison had made sure Catherine couldn’t communicate with her.

Helen searched for information about Alice Lel.

She found her in census records and society pages, unmarried, living on her own substantial inheritance, active in women’s suffrage organizations.

If anyone had fought for Catherine, Helen thought it would have been Alice.

She was right.

In the archives of the Massachusetts Women’s Suffrage Association, Helen found correspondence from Alice Lel dated throughout 1909 and 1910.

Desperately seeking legal help to free her sister from Danvers.

The letters from Alice Lel painted a picture of a determined woman fighting against impossible odds.

In April 1909, she wrote to a lawyer, “I visited my sister Catherine at Danvers and found her lucid, rational, and desperate to be freed.

She is not insane.

She has been imprisoned by her husband because she tried to protect her daughters from his violence.

But every lawyer I consult tells me the same thing.

A husband’s word is law, and there is no legal mechanism to challenge a man’s decision to institutionalize his wife.

Helen found Alice’s correspondence with suffrage leaders, including Susan B.

Anony’s protege, Anna Howard Shaw.

Alice wrote, “This is precisely why we must have the vote.

My sister is being tortured in a prison called a hospital and I am powerless to help her because I am merely a woman and her husband is a respected man.

But Alice didn’t give up.

Helen discovered she had done something extraordinary.

She had hired a private investigator to document William Harrison’s behavior.

The investigator’s report dated June 1909 was damning.

The report documented Harrison’s visits to private clubs known for prostitution, his drinking, his violent outbursts at staff and colleagues, and disturbing testimony from a former housemmaid who claimed she had witnessed him striking his daughters and threatening them into silence.

Armed with this evidence, Alice tried again to get Catherine released.

She brought the report to hospital administrators at Danvers, arguing that Catherine’s delusions of persecution were actually accurate descriptions of abuse.

The response preserved in hospital records was chilling.

Mrs.

Harrison’s supposed evidence is clearly fabricated by her sister, who is known to be involved in radical women’s movements.

Dr.

Harrison has provided testimony that his sister-in-law is attempting to undermine his authority over his own family.

Mrs.

Harrison’s belief that this evidence will free her only confirms her delusional state.

They used Alice’s activism against her, and they used Catherine’s hope against her as well.

But Alice found one ally, Dr.

Margaret Cleaves, one of the few female physicians in Boston, who was willing to examine Catherine independently.

In August 1909, Dr.

Cleaves visited Danvers and interviewed Catherine extensively.

Her report was unequivocal.

I find no evidence of hysteria, delusions, or any mental illness.

Mrs.

Harrison is clearly traumatized by her experiences but is entirely rational.

She provides consistent detailed accounts of abuse by her husband.

Her commitment appears to be a misuse of medical authority for purposes of control.

Dr.

Cleaves submitted her evaluation to Danver’s administrators and to the state board of health.

Helen found the responses in archives.

Both institutions dismissed the evaluation with one administrator writing, “Dr.

Cleaves is known for her sympathies to feminist causes which clearly color her judgment.

Catherine remained imprisoned at Danvers and Alice’s fight seemed feudal.

But Helen noticed something in the records.

Alice never stopped trying.

Helen had focused so intensely on Catherine’s fate that she had nearly forgotten about the three daughters in the photograph.

She returned to census and city records, tracing what happened to Margaret, Dorothy, and Clara after their mother was institutionalized.

The 1910 census listed all three girls living at 287 Beacon Street with their father.

But by the 1920 census, only Margaret, now 24, was still listed at that address.

Dorothy and Clara were nowhere to be found in Boston records.

Helen expanded her search nationwide.

She found Dorothy in New York City’s 1920 census, living in a boarding house, working as a seamstress.

She had left Boston as soon as she turned 18 in 1917.

Clara was harder to find.

Helen searched for years, checking records in multiple states.

Finally, she found her, but in a place Helen didn’t expect.

The 1920 census for Danvers, Massachusetts, listed Clara Harrison, age 18, as a resident of Danver State Hospital.

Helen’s heart sank.

Clara, the terrified little girl in the photograph, had ended up in the same institution as her mother.

But when Helen examined the records more carefully, she realized Clara wasn’t a patient.

She was listed as household member, someone living at the facility, but not committed.

Further investigation revealed that Alice Lel had arranged for Clara to live at Danvers in a staff cottage where she helped with administrative work.

Alice had found a way to keep Clara close to Catherine without putting her back under William Harrison’s control.

Helen found correspondence from Clara in the Massachusetts Historical Society’s suffrage collection.

A letter dated 1921 when Clara was 19.

Dear Miss Shaw, my aunt Alice has encouraged me to write to you about my experiences.

For years, I believe my mother was truly ill as my father claimed.

But living here, seeing her daily, I know the truth.

She is not insane.

She never was.

Everything she told me as a child about needing to protect us, about the danger we were in, was real.

I was too young to understand then.

I understand now.

Helen found more letters from Clara written over several years.

She had become an advocate for reforming commitment laws, speaking at suffrage meetings about how women were being imprisoned in asylums by abusive husbands.

In 1923, Clara testified before the Massachusetts State Legislature as they considered a bill requiring independent medical evaluation before commitment.

She brought the 1908 photograph with her.

A newspaper account described her testimony.

“Miss Clara Harrison held up a family portrait from 15 years ago.” “This is me at age six,” she told the legislators.

“I am looking at my father who was threatening us even as we posed for this picture.” That same year, he had my mother locked away for trying to protect us.

For 15 years, she has been imprisoned in Danvers, diagnosed as insane for telling the truth.

The bill passed.

It was a small victory, but Helen saw Clara’s courage in using the photograph, the same image that had captured her terror, as evidence and testimony.

Helen’s research revealed that Katherine Harrison was finally released from Danver State Hospital in 1924 after 16 years of imprisonment.

The new commitment law required a re-evaluation of long-term patients by independent physicians.

Three doctors examined Catherine and found no evidence of mental illness.

She was 50 years old when she walked out of Danvers, her youth and health destroyed by forced treatments and institutionalization.

But she wasn’t alone.

Alice and Clara were waiting for her.

Helen found records showing that Catherine lived with Alice in a house on Marlboro Street.

Dorothy came from New York for the reunion.

Only Margaret stayed away.

She had married in 1919 and apparently chosen to maintain distance from the family’s painful history.

William Harrison had died in 1922.

His obituary praising him as a dedicated physician and devoted father with no mention of the truth.

Helen discovered something remarkable in Alice Lel’s papers.

Donated to the Massachusetts Historical Society after her death in 1947.

Among her belongings was the original 1908 photograph, not a studio copy, but the actual print that Catherine had commissioned.

On the back in Catherine’s handwriting was a note dated March 1908.

This photograph shows the truth that I cannot speak aloud.

My youngest daughter sees the danger.

My other daughters have learned to hide their fear.

I have tried to smile as expected, but none of us are safe.

I am leaving this with the photographer in hopes that if something happens to me, someone will see what is really in this picture and know that I tried to protect my children.

Catherine.

Catherine had planned ahead.

She had known the photograph might be her only testimony if she was silenced, and she had been right.

Helen arranged to meet with descendants of the Harrison family in November 2024.

Two of Clara’s grandchildren, Robert and Anne, came to Boston to see the research and the photograph that had started everything.

We knew Grandma Clara had a difficult childhood, Robert said, looking at the image.

But she never talked about details.

She only said that her mother had been treated terribly and that she’d spent her life trying to make sure other women didn’t suffer the same way.

Anne wiped tears from her eyes.

Look at her face.

She’s just a baby and she’s so scared.

She turned to Helen.

What happens to this now? Does it just go back in the archives? That’s up to you, Helen said.

This is your family’s story.

Robert and Anne decided to donate the photograph and all associated documents to a new exhibition on domestic violence and women’s rights history at the Boston Women’s Heritage Trail.

The exhibition titled Silence No More opened in March 2025.

At the opening, Anne spoke to a crowd of over 300 people.

This photograph was taken 117 years ago as a silent cry for help.

My great great grandmother Catherine tried to use it to prove what was happening to her family.

She was punished for telling the truth, imprisoned for 16 years for the crime of protecting her children.

She gestured to the enlarged photograph on the wall, but her plan worked, just not in her lifetime.

This image survived.

It bore witness when she couldn’t.

And now, finally, people see the truth that’s been hiding in plain sight for more than a century.

The exhibition included Catherine’s note from the back of the photograph, Joseph Foster’s journal entries, Alice Lel’s correspondence, Clara’s testimony to the legislature, and modern statistics on domestic violence.

Helen stood in the gallery watching visitors stop before the photograph, seeing the fear in Clara’s eyes, understanding what Catherine had tried to do.

The image that had been filed away as just another family portrait had become a powerful piece of evidence.

not just of one family’s suffering, but of the systemic silencing of women’s voices.

Sometimes, Helen thought, a photograph captures more truth than anyone realizes at the time, and sometimes, if we’re willing to look closely enough, those truths find their way back to the light.

Catherine’s photograph had finally fulfilled its purpose.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load