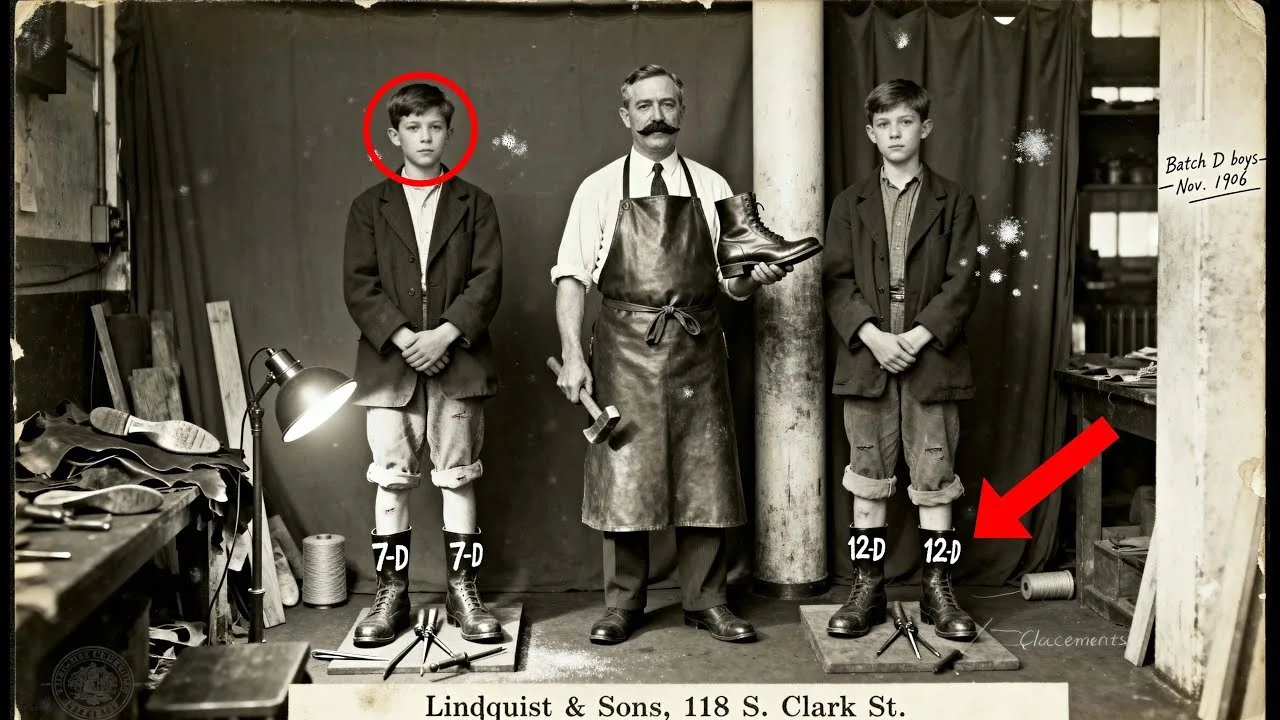

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots.

At first glance, it seems like nothing more than a slice of immigrant Chicago, a craftsman posing with two young helpers, the kind of photo that ends up in a museum exhibit about the dignity of labor.

But one detail refused to stay quiet.

And the deeper someone looked, the more they realized that this image was not a portrait of honest work.

It was a receipt.

Nadia Kowalsski had been processing donations for the Chicago History Museum for 11 years.

Most of what crossed her desk was predictable.

Old maps, framed stock certificates, tarnished metals from wars nobody remembered.

But in the summer of 2019, a sealed box arrived from the estate of a demolished building on West Van Beern Street.

The building had once housed a shoe repair business, then a check cashing outlet, then nothing at all.

When the wrecking crew came, someone found a metal lock box in a wall cavity.

Inside were receipts, tools, and a single cabinet card photograph in a paper sleeve.

The photo showed a narrow workshop cluttered with leather scraps, wooden shoe forms, and hand tools.

In the center stood a man in his 40s with a waxed mustache, and a leather apron.

He looked proud, prosperous.

Flanking him on either side were two boys, maybe 10 or 12 years old.

They wore matching dark jackets and trousers, hands folded in front of them, expressions blank.

Behind them, a painted backdrop suggested a much grander room than the one they actually stood in.

Nadia scanned the image at high resolution, the way she did with everything.

She noted the careful staging.

The shoemaker held a half-finished boot in one hand, a hammer in the other.

The boys each held smaller tools.

Their posture suggested they had been told exactly where to stand and how to hold their bodies.

standard practice for studio portraits of the time.

Nothing unusual.

Then she zoomed in on the boy’s boots.

Both pairs had chalk marks on the outer ankle, not scuffs, not wear.

Deliberate marks, a number on the left boot, a letter on the right.

The boy on the left wore seven and D.

The boy on the right wore 12 and D.

Nadia stared at those marks for a long time.

She had seen chalk marks like that before in photos of livestock auctions and warehouse inventories.

They were lot numbers.

She turned the photo over.

On the back in pencil, someone had written wrecked two from Harmon batch D.

Nov 1906 satisfactory.

This was not just a portrait of a shoemaker and his apprentices.

Something here was deeply wrong.

Nadia had spent more than a decade looking at photographs of turn of the century Chicago.

She had seen tenement families posed in front of painted backdrops trying to look wealthier than they were.

She had seen factory owners surrounded by their workers projecting benevolence.

She had seen children in formal clothes, children in rags, children in coffins, but she had never seen children marked like inventory.

She pulled out her magnifying loop and examined the boy’s faces.

They were not smiling.

Their eyes were focused somewhere past the camera, as if looking at something far away.

The boy on the left had a faint bruise along his jawline, visible only at high magnification.

The boy on the right had a small scar on his forehead, half hidden by his cap.

These were not the faces of apprentices learning a trade they had chosen.

These were the faces of children who had learned not to react.

The next morning, Nadia removed the photograph from its sleeve and examined the card stock itself.

Cabinet cards of this era often carried the photographers’s studio name embossed or printed along the bottom edge.

This one had a faint stamp.

Linquist Sons 118 S.

Clark Saint.

She made a note.

Then she looked at the paper sleeve.

It was yellowed and brittle, but it bore a printed label.

Harmon Industrial Relief Society Chicago Office file copy.

She knew that name, or at least she thought she did.

Industrial relief societies had been common in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

They provided job training, housing, and placement services for the poor.

Some were attached to churches, some were run by wealthy reformers, some were legitimate, and some, as Nadia was beginning to suspect, were something else entirely.

She began with the photographer.

Linquist and Sons had operated on South Clark Street from 1889 to 1914.

According to city directories, they specialized in commercial and industrial portraits, factories, workshops, trade schools.

They had contracts with several large employers to document their workforce.

Nothing unusual there.

But one detail stood out.

A 1907 newspaper clipping mentioned that Linquist and Sons had been the preferred studio for several private relief agencies, including the Harmon Industrial Relief Society.

The agencies paid Linquist to photograph their placements as a form of recordkeeping.

Placements.

That was the word that began to haunt Nadia.

She moved to the Harmon Industrial Relief Society itself.

The organization had been founded in 1891 by a man named Elias Harmon, a grain merchant who had made his fortune in the 1880s.

According to his obituary, Harmon had been moved by the plight of orphaned and abandoned children in Chicago’s poorest neighborhoods.

He established the society to rescue these children from the streets and place them with respectable tradesmen who would teach them a skill.

The obituary called him a philanthropist.

It called his work a blessing.

But Nadia found other records in the archives of the Cook County Juvenile Court.

She located a 1909 complaint filed by a woman named Agada Noak.

Noak claimed that her son Stfan had been taken from her by agents of the Harmon Society after she was briefly hospitalized for influenza.

She had never signed any papers.

When she recovered and tried to reclaim him, she was told that Stefan had been placed with a tradesman and that his records were confidential.

Met the complaint was dismissed.

The judge noted that Noak was a widow, a Polish immigrant, and that she had no fixed means of support.

Stefan was never returned.

Nadia found three more complaints from the same year.

All involved immigrant mothers, all involved children taken during periods of illness or temporary hardship.

All were dismissed.

She called Dr.

Marcus Oellerin, a historian at Northwestern, who specialized in child welfare policy before the New Deal.

She had worked with him on a previous exhibit about Hull House.

When she described the photograph in the records she had found, he was quiet for a long moment.

“You’re looking at something that was perfectly legal,” he said, “and perfectly monstrous.” He explained that private relief societies in this era operated with almost no oversight.

They were not government agencies.

They were not required to keep public records or follow standardized procedures.

They received funding from wealthy donors who trusted them to do good work.

And they had enormous power over the lives of poor children.

The language they used was always benevolent.

Oellerin said rescue placement training.

But what they were really doing in many cases was supplying cheap labor to businesses that didn’t want to pay adult wages.

The children had no legal standing.

Their parents, if they had any, were usually too poor or too foreign to fight back, and the agencies kept their records private, which meant there was no way to track what happened to these kids.

He paused.

You said the boots had chalk marks.

Numbers and letters, Nadia said.

Like a lot numbers.

That’s consistent with what I’ve seen in other cases.

Some agencies literally auction children off in batches.

They’d bring a group of kids to a meeting hall, let the tradesmen inspect them, and then assign them based on bids.

The chalk marks were for sorting.

It was livestock logic applied to children.

Nadia felt something cold settle in her stomach.

And the photograph, proof of delivery, said the tradesman got a copy to show he had received the goods.

The agency kept a copy for their files.

It was a business transaction documented like any other.

He agreed to help her dig deeper.

Over the following weeks, they assembled a picture of the Harmon Industrial Relief Society that bore no resemblance to the glowing obituary.

The organization had placed thousands of children between 1891 and its quiet dissolution in 1918.

It had contracts with shoemakers, tailor, blacksmiths, and factories across the Midwest.

It charged tradesmen a placement fee and collected a portion of the child’s notional wages.

It kept its records in a private archive that was never turned over to any public authority, but fragments survived.

Oellerin located a partial ledger in the papers of a lawyer who had represented the society in a 1911 lawsuit.

The ledger listed children by number and batch, not by name.

It recorded their ages, physical descriptions, and the assignments.

It noted which children had been returned for being unsatisfactory and which had been reassigned.

It also noted which children had expired.

Expired like a lease.

The ledger covered only a few months of 1906, but it was enough.

Batch D, the batch mentioned on the back of the photograph, contained 14 boys.

Two of them had been assigned to a shoemaker on West Van Beern Street.

Their numbers were 7 and 12.

Their names were not recorded.

Nadia began searching for the shoemaker.

His name, according to city directories, was Henrik Bergstrom.

He had operated a shoe repair business at the Van Buran address from 1902 to 1923.

He had a wife, no children of record, and a modest estate when he died in 1931.

His probate file contained an inventory of his tools and equipment, which matched the items visible in the photograph.

It also contained a curious notation.

Various debts to harm society.

Settled.

1918.

Settled.

Not paid.

Settled.

As if there had been a negotiation, as if something had been exchanged.

Nadia traveled to the site of the old Bergstrom workshop.

The building was gone, replaced by a parking lot.

But two blocks away, she found the Cook County Record Center, where she had once spent weeks researching a different project.

She requested everything they had on Henrik Bergstrom and the Harmon Industrial Relief Society.

The archavist, a woman named Lorraine, remembered her.

“You always find the dark ones,” Lorraine said.

“What Nadia found was a series of contracts.

The Harmon Society had supplied Bergstrom with a rotating cast of boys over a 15-year period.

The contracts called them apprentices, but specified that they were not entitled to wages, only maintenance.

They could not leave the premises without permission.

They could not contact their families if any were known.

They were obligated to work such hours as the tradesman requires.

And if they ran away, the tradesmen could report them to the police as truent or thieves, and the society would supply a replacement.

One contract dated 1908 included a handwritten note.

Returned number seven, unsuitable.

Persistent complaints.

Request sturdier stock.

returned like a defective product.

Nadia found no record of what happened to the boy who had been number seven.

She found no record of what happened to most of the boys in the ledger.

Their names had never been recorded.

Their fates had never been tracked.

They had entered the system as numbers and left it as ghosts.

But she found one name.

In a 1912 issue of a Polish language newspaper, she located a small article about a young man named Stefan Noak.

He had been found dead in an alley on the south side, apparently from exposure.

The article noted that Noak had told neighbors he had once been sold to a shoemaker as a child and had run away when he was 16.

He had never found his mother.

He had never learned to read.

He had spent his adult years doing odd jobs and sleeping in doorways.

Stefan Noak, the son of Ageda Noak, the boy whose complaint had been dismissed in 1909.

Nadia sat with that article for a long time.

She thought about the photograph on her desk.

She thought about the two boys with chalk marks on their boots standing in a cramped workshop looking at something far away.

She thought about the word satisfactory written on the back.

She decided that this story could not stay in a filing cabinet.

Nadia brought her findings to the museum’s curatorial committee in October 2019.

She had prepared a presentation with scans of the photograph.

the contracts, the ledger fragments, and the newspaper articles.

She proposed a small exhibit, perhaps a single display case that would use the Bergstrom photograph to tell the story of child labor trafficking in progressive era Chicago.

The response was not what she expected.

The committee chair, a woman named Dr.

Evelyn Marsh, listened carefully and then asked how Nadia could be certain that the Harmon Society was engaged in trafficking rather than legitimate charity work.

The language of the contracts is troubling, Marsh said.

But we have to be careful about imposing modern judgments on historical practices.

Apprenticeship was a common and accepted system.

Nadia pointed to the chalk marks.

She pointed to the word expired.

She pointed to Stefan Noak dead in an alley at 23.

We don’t know that these things are connected, Marsh said.

We have fragments.

We have inferences.

We don’t have proof that any specific child in this photograph was harmed.

A board member named Richard Callaway spoke up.

He was a retired banker who had donated generously to the museum’s renovation.

I think we need to consider the broader implications, he said.

If we present this as a story about trafficking, we’re making a serious accusation against a charitable organization that many prominent Chicago families supported.

Some of those families are still prominent.

Some of them are donors.

The room went quiet.

Nadia looked around the table.

She saw discomfort.

She saw calculation.

She saw people who were not evil, just cautious, just practical, just worried about money and reputation and the thousand small compromises that kept institutions running.

The Harmon Society dissolved over a hundred years ago.

She said, “Everyone involved is dead.” But the narrative persists.

Callaway said, “If we say that respected Chicago businessmen participated in child trafficking, we’re saying something about the city’s history that some people will find offensive.

We’re saying something about the progressive era that complicates the usual story.

We’re opening ourselves to controversy.” Dr.

Olar, who had come to support Nadia’s presentation, leaned forward.

“With respect,” he said, “the usual story is a lie.

The progressive era was full of reformers who genuinely wanted to help people.

It was also full of people who exploited the language of reform to run what amounted to slave markets for children.

Both things are true if we only tell the comfortable version.

We’re not doing history.

We’re doing public relations.

The committee voted to table the proposal for further review.

Nadia understood what that meant, but she had allies.

A junior curator named David Chen had been quietly horrified by the committee’s response.

A graduate student named Aisha Williams, who was researching labor history for her dissertation, offered to help dig deeper, and Dr.

Oilarn had contacts at the Chicago Tribune who were interested in stories about forgotten injustices.

Over the following months, they built a case that could not be ignored.

Williams found more ledger fragments in the papers of a defunct law firm.

Chen located photographs from other Harmon placements in the museum’s own collection.

Photographs that had been cataloged as innocent trade portraits, but that bore the same telltale chalk marks.

Oellerin connected them with descendants of Harmon society victims who had been searching for answers for generations.

One of those descendants was a woman named Patricia Kowaltic.

Her greatg grandmother, a Polish immigrant named Zofhia, had lost two sons to the Harmon Society in 1904.

Zofhia had spent years trying to find them.

She had written letters.

She had visited offices.

She had been turned away, ignored, threatened.

She had died in 1941 without ever learning what happened to her boys.

Patricia had grown up hearing the story.

She had always believed it, but she had never been able to prove it.

When Nadia showed her the ledger entries that matched her great uncle’s ages and descriptions, Patricia wept.

They were numbers, she said.

They were never even given the dignity of names.

In the spring of 2020, the Tribune ran a long feature on the Harmon Industrial Relief Society.

The story included the Bergstrom photograph, the contracts, the ledger fragments, and interviews with descendants.

It documented a system in which thousands of children had been taken from vulnerable families, stripped of their identities, and rented out to businesses that worked them without wages and discarded them when they were no longer useful.

It named the prominent families who had funded and directed the society.

It traced the money.

The response was immediate and divided.

Some readers thanked the paper for exposing a forgotten crime.

Others accused it of sensationalism, of attacking the reputations of respected families, of cancelling history.

The museum received letters demanding that it never display the Bergstrom photograph and letters demanding that it build an entire wing around it.

Dr.

Marsh called an emergency meeting of the curatorial committee.

This time the conversation was different.

The story was out.

The question was no longer whether to tell it, but how.

In September 2021, the Chicago History Museum opened a new permanent display in its labor history gallery.

At the center was the Bergstrom photograph enlarged and annotated.

Beside it were copies of the Harmon Society, contracts, the ledger fragments, and the newspaper articles about Stefan Noak.

A video screen played recorded testimonies from descendants, including Patricia Kowaltic.

The display did not accuse any living person of any crime.

It did not claim to know exactly what happened to every child in the system, but it told the truth about what the system was.

It explained the chalk marks.

It named the practice.

and it centered the voices of those who had suffered.

On the day the exhibit opened, Patricia Kowalic stood in front of the photograph for a long time.

She had brought a small bouquet of flowers which she placed beneath the display case.

A museum guard started to object, then thought better of it.

“My great-g grandandmother never stopped looking,” Patricia said to Nadia.

She went to her grave, not knowing if her boys were alive or dead.

“Now at least someone knows they existed.

Someone knows they weren’t just numbers.” Nadia thought about all the other photographs in the museum’s collection, the proud factory owners, the smiling apprentices, the orderly workshops.

She thought about how many of them might contain the same hidden marks, the same buried stories.

She thought about how easy it is to look at an old photograph and see only what the photographer wanted you to see.

The Bergstrom photograph had been taken to document a transaction.

It had been kept to prove that goods had been delivered.

For over a century, it had sat in a wall cavity, forgotten, and now it was evidence of something that respectable people had preferred to forget.

There are thousands of photographs like this in archives and atticss across the country, portraits of tradesmen with their helpers, factory floors with rows of small workers, domestic scenes with servants standing just at the edge of the frame.

They look like records of ordinary life.

They look like proof that the past was simpler, more industrious, more honest.

But look closer.

Look at the hands.

Look at the feet.

Look at the chalk marks and the lot numbers and the faces that do not quite match the pose.

The camera was never neutral.

It was always a tool of the people who paid for it.

And sometimes, if you know how to look, you can see the people it was meant to erase.

The boys in the Bergstrom photograph never got to tell their own story.

They never got to say their own names.

They were processed, marked, delivered, and forgotten.

But they were not erased.

They left a trace, a tiny piece of evidence that someone someday would know how to read.

Every old photograph is an argument about what mattered and what did not.

Every old photograph is a choice about who gets to be seen and who gets to be invisible.

And sometimes the most important thing in the frame is the thing the photographer never meant to show

News

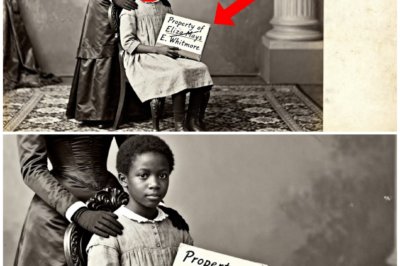

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1868 Portrait of a Teacher and Girl Looks Proud Until You See The Bookplate

This 1858 studio portrait looks elegant until you notice the shadow. It arrived at the Louisiana Historical Collection in a…

End of content

No more pages to load