The Photograph That Refused to Stay Silent

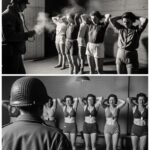

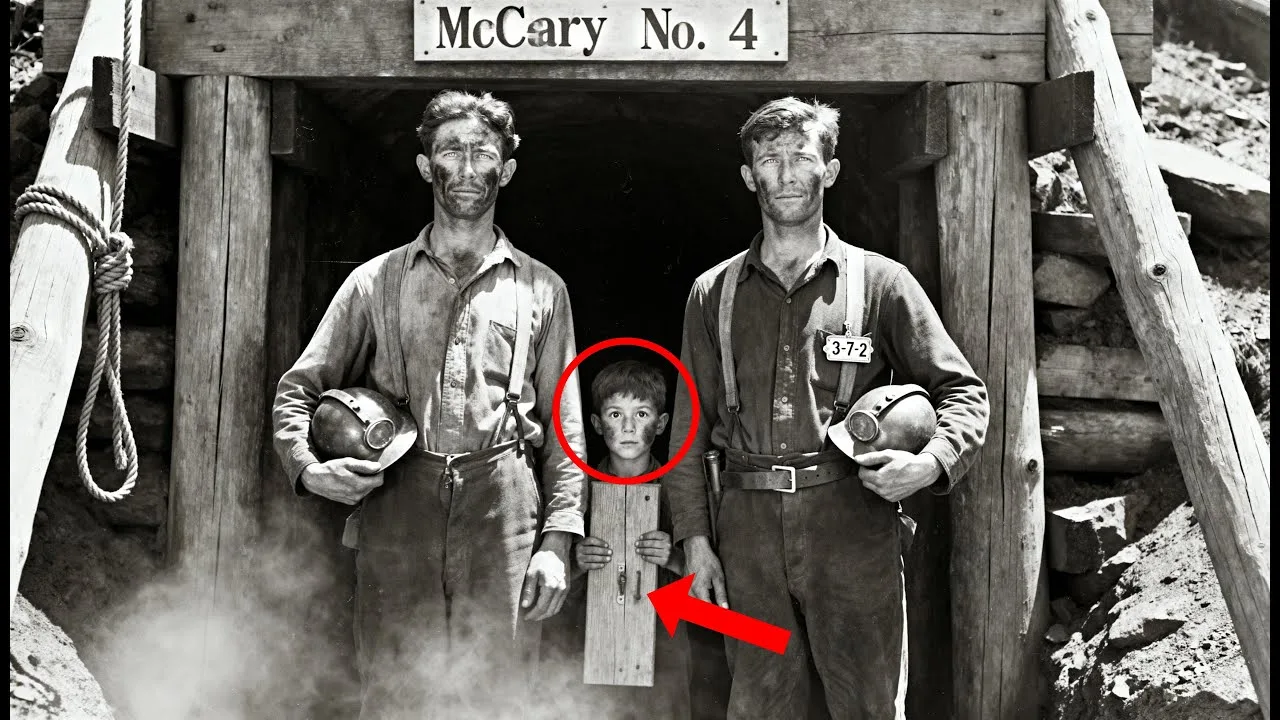

At first glance, it is just another workday photograph.

Two men, begrimed and proud, stand at the mouth of a coal shaft with their helmets held like trophies.

The composition is textbook, the lighting sharp—someone wanted this image to say something about American industry, about masculine labor, about the dignity of hard work.

But there is something in the negative space between their shoulders.

Something that should not be there at all.

Dr.Sarah Kendrick found the photograph in a cardboard box at an estate sale in Charleston, West Virginia.

She had been buying up old mining ephemera for nearly twenty years, ever since she started working as a labor historian at a small liberal arts college two hours north of the coal fields.

She knew these images well, the posed dignity of men who spent their days in darkness, the company photographers who made them look heroic for promotional calendars and insurance brochures.

She had seen hundreds of these portraits, and they all told the same sanitized story.

But this one stopped her cold.

## Chapter 1: The Child in the Shadows

The two miners dominate the frame.

They wear canvas work pants and collarless shirts blackened by coal dust.

Their faces are streaked with grime except around their eyes where sweat has washed the skin almost clean.

Behind them, the timber frame of the shaft entrance is visible and beyond that only darkness.

Sarah held the print up to the afternoon light coming through the barn’s dirty windows.

That is when she saw him.

Between the two miners in the narrow gap where their shoulders did not quite meet, a small face emerged from the shadows of the mine entrance.

At first, she thought it was a trick of the light.

A smudge, a flaw in the paper, but the more she looked, the clearer it became.

A child, perhaps nine or ten years old.

His face was dark with soot, but his eyes were unmistakable.

Wide, alert, looking directly at the camera.

He wore no helmet.

His hands, barely visible at the bottom edge of the gap between the miners, appeared to be holding something—a wooden stick or tool.

His body, what little could be seen, was angled forward, as if he had been caught midstep trying to stay in the frame or perhaps trying to leave it.

Sarah paid twelve dollars for the entire box and carried it to her car.

Back in her office, she set the photograph on her desk under the bright ring of her magnifying lamp.

The image was a gelatin silver print mounted on thick card stock.

On the back, written in faded pencil: “McCreary number four, September 1905, property of Alagany Coal and Iron Company.”

This is not just a pretty old photo.

Something here is wrong.

## Chapter 2: The Law and the Lie

Sarah Kendrick had spent two decades studying labor history in the central Appalachian coal fields.

She had written her dissertation on union organizing in the first decade of the twentieth century and published articles on immigrant miners and industrial accidents.

She knew the visual grammar of these company photographs.

They were propaganda.

They showed strong men doing dangerous work.

They never showed what the companies wanted to hide—child labor, for instance.

She adjusted her desk lamp and leaned in close.

The boy’s face was undeniably there.

He was small, thin, and positioned in a way that suggested he had not been meant to appear in the photograph at all.

Perhaps he had wandered into the frame at the last second.

Perhaps he had been standing there the whole time, and the photographer had not noticed him in the dimness of the shaft entrance.

Either way, his presence in the image contradicted the entire purpose of the portrait.

By 1905, West Virginia had passed a law prohibiting boys under the age of twelve from working in mines.

The law was vaguely worded and poorly enforced, but it existed.

Companies that wanted to maintain respectable reputations made sure their official payrolls did not include obvious violations.

They sent their promotional photographs to investors and union negotiators and progressive reformers in the north.

Those photographs could not show children.

And yet, here was a child.

Sarah removed the print from its cardboard backing and examined the edges.

No signs of retouching, no evidence of a composite image.

The photograph appeared to be a single exposure.

She flipped it over again and studied the studio stamp.

McCreary number four almost certainly referred to a mine.

The Alagany Coal and Iron Company operated several large operations in Fayette and Raleigh counties during this period.

She pulled out her laptop and searched her database of historical mining company records.

McCreary number four had been a medium-sized operation, employing between 150 and 200 men at its peak.

The mine had closed in 1932, and the company had been absorbed by a larger conglomerate during the Depression.

Most of its records had been lost or destroyed.

But Sarah had a contact, a retired archivist named William Oaks, who had spent thirty years working for the West Virginia Division of Culture and History.

If anyone knew where to find surviving documents from Alagany Coal and Iron, it was him.

## Chapter 3: The Hidden Payroll

She called him that evening.

“McCreary number four,” he repeated slowly.

“I remember that name.

There was a disaster there in 1907.

Gas explosion killed fourteen men.

Do you have anything on it? Payroll records? Accident reports?”

“The accident report? Maybe, but payroll?” He paused.

“Alagany Coal was notorious for losing records.

There were rumors that after the labor inspectors started coming around in 1904, the company started destroying anything that could get them fined.”

Sarah looked at the photograph again.

The boy’s eyes stared back at her.

“I have a photograph,” she said.

“From September 1905, it shows two miners and what looks like a child worker too young to be legal.”

William was quiet for a moment.

Then he said, “You need to talk to Linda Ree.”

Linda Ree was a historian specializing in child labor in the American coal fields.

She had written a book on breaker boys in Pennsylvania and was working on a second project about underground child labor in West Virginia and Kentucky.

Sarah called her the next morning and described the photograph.

“Can you send me a scan?” Linda asked.

Sarah scanned the image at high resolution and emailed it.

Ten minutes later, her phone rang.

“That’s not a breaker boy,” Linda said immediately.

“Breaker boys worked above ground sorting coal.

That child is inside the mine.”

“What would he have been doing?”

“Trapping.

Opening and closing ventilation doors to direct air flow.

It was one of the most common jobs for young boys.

Dangerous as hell.

They worked alone in the dark for ten or twelve hours a day.

If they fell asleep and left a door open, the whole mine could fill with gas.”

Sarah felt something tighten in her chest.

She looked at the photograph again at the boy’s small hands holding that wooden stick.

“Could that be a door prop?” she asked.

“Maybe.

Or a tool for prying the door open when a coal car came through.

Either way, if that boy was working as a trapper in September 1905, he was breaking the law.

And Alagany Coal knew it.”

Sarah thanked her and hung up.

She sat at her desk for a long time staring at the image.

The two miners looked so proud, so solid.

They had probably sent copies of this photograph home to their families.

They had no idea that the camera had captured something their employer desperately wanted to hide.

## Chapter 4: The Disappeared Children

She started building a timeline.

In 1904, West Virginia had passed its first meaningful child labor law.

Boys under twelve could not work in mines.

Boys under fourteen could not work underground.

The law had been pushed through by progressive reformers and union organizers, and it had been bitterly opposed by coal operators who relied on cheap child labor to keep costs low.

Some companies complied.

Most found ways around it.

Sarah searched through newspaper archives and found dozens of articles about labor inspectors visiting mines throughout Fayette and Raleigh counties in 1905 and 1906.

The inspectors filed reports.

The companies paid small fines and then mysteriously the records disappeared.

She visited the West Virginia State Archives in Charleston and requested everything they had on the Alagany Coal and Iron Company.

The archivist brought her three boxes.

Most of it was mundane—incorporation documents, annual reports to shareholders, letters from investors.

But in the third box, she found something useful: a handwritten ledger dated 1904 listing mine employees by name, age, and job title.

The entries were neat and methodical.

Each worker had a number.

Each job had a wage.

And at the bottom of several pages in a different hand, someone had written, “Records incomplete.

C superintendent.” There were no entries for 1905.

Sarah photographed every page of the ledger and then asked the archivist if there were any other surviving documents from McCreary number four.

“Not much,” the archivist said.

“The company was pretty aggressive about cleaning out their files after the mine closed.

There might be something at the county courthouse in Fayetteville.

Property records, tax assessments, that sort of thing.”

Sarah drove to Fayetteville the next day.

The courthouse was a solid brick building on a hill overlooking the New River Gorge.

Inside, the clerk directed her to the basement archives where rows of metal shelving held deed books and court records dating back to the 1860s.

She spent three hours going through boxes labeled Fayette County Mining Companies, 1900–1910.

She found tax records for McCreary number four.

She found property deeds.

She found a lawsuit filed by a widow whose husband had been killed in a roof collapse in 1903.

And then she found the coroner’s reports.

There were four of them filed between March and November 1905.

All of them involved boys under the age of fourteen.

All of them had died inside McCreary number four.

– The first was a twelve-year-old named Thomas.

Cause of death: crushed by coal car.

– The second was a ten-year-old named Amos Fletcher.

Cause of death: asphyxiation, probable gas exposure.

– The third was a thirteen-year-old named Samuel Kowalski.

Cause of death: blunt trauma, fall from scaffolding.

– The fourth had no name at all, just a description: Negro boy, age approximately nine.

Cause of death unknown, body recovered from lower gallery.

None of these deaths appeared in any of the Alagany Coal and Iron Company’s official records.

Sarah sat in the dim basement of the courthouse and read the coroner’s reports three times.

The language was clinical.

The details were sparse.

But the pattern was undeniable.

These boys had been working inside the mine, doing jobs that were illegal under the new law, and the company had buried the evidence.

## Chapter 5: The Invisible Number

She photographed the documents and returned to her office.

That night, she could not sleep.

She kept thinking about the boy in the photograph, the one whose name she did not know, the one who had been standing in the shadows, holding a stick, staring at the camera.

Was he one of the boys in the coroner’s reports? Or had he survived? And if he had survived, what had his life been like?

Sarah spent the next two weeks building the story.

She contacted descendants of miners who had worked at McCreary number four.

She found census records that listed families living in the coal camps surrounding the mine.

She located union organizers’ memoirs that described conditions inside West Virginia mines in the early 1900s.

One passage from a pamphlet published by the United Mine Workers in 1906 stood out:

> “The operators claim they obey the child labor law, but every miner knows the truth.

Boys as young as eight work inside the shafts, opening doors, carrying water, picking slate.

The companies keep no records of these boys.

They pay them in script, not cash.

If a boy is killed, his body is carried out in secret, and his family is told to stay quiet.

The operators say there are no children in the mines.

The operators are liars.”

Sarah had the photograph professionally digitized and enhanced.

The lab technician, Clare, zoomed in on the boy’s face.

“You can see details in his clothing,” Clare said, pointing at the screen.

“He’s wearing a shirt that’s too big for him.

And look here at his hands.

That’s not a stick.

That’s a door prop.

Trappers used them to hold ventilation doors open when coal cars went through.”

“Can you see anything else?” Sarah asked.

Clare adjusted the contrast.

“There’s something on his chest.

Maybe a number pinned to his shirt.

Companies did that sometimes.

Gave each worker a number instead of using names.”

Sarah leaned closer.

The number was barely visible, but it was there: 372.

She went back to the 1904 ledger and scanned through the entries.

Most workers were listed by name, but a few had numbers.

They were all listed as casual labor or day workers, and all of them were paid significantly less than the regular miners.

Number 372 did not appear in the ledger.

But Sarah noticed something else.

In the margins of several pages, someone had written notes in pencil.

Most were illegible, but one next to a crossed out name read, “Moved underground.

No record.”

The pieces were coming together.

Alagany Coal and Iron had hired child workers, paid them off the books, and assigned them numbers instead of names.

When labor inspectors came around, the company hid the boys in the deepest parts of the mine or sent them home for the day.

And when the boys were killed, the company erased them from the official record.

The photograph was an accident, a moment of carelessness.

The two miners had posed for a company portrait meant to show the dignity and strength of American labor.

And in the background, almost invisible, a child stood holding the tool of his illegal trade.

## Chapter 6: The Truth Emerges

Sarah wrote a 5,000-word article and submitted it to a regional history journal.

The editor accepted it immediately.

Three weeks later, she got a phone call from a woman named Margaret Howell.

“My great-grandfather worked at McCreary number four,” Margaret said.

“I saw your article online.

I think I know who that boy is.”

They met at a coffee shop in Charleston.

Margaret brought a small cardboard box.

“My great-grandfather was named John Howell,” she said.

“He was one of the miners in your photograph, the one on the left.” Sarah looked at the image on her laptop screen.

The miner on the left had a square jaw and deep-set eyes.

She could see the resemblance.

“He never talked much about the mine,” Margaret continued.

“But before he died, he told my grandmother something.

He said there were boys working underground, young boys, and he said the company made them invisible.”

Margaret opened the box and pulled out a faded envelope.

Inside were three photographs.

All of them showed groups of miners standing outside McCreary number four, and in two of them in the background, barely visible, were children.

“My great-grandfather kept these hidden,” Margaret said.

“I think he felt guilty.

He knew what was happening, and he didn’t stop it.”

Sarah studied the photographs.

In one, a boy who could not have been older than eight stood next to a coal car holding a pickaxe.

In another, two boys sat on the ground eating from tin lunch pails, their faces black with coal dust.

“Why didn’t he say anything?” Sarah asked.

Margaret shook her head.

“Because if he did, he would have lost his job and his family would have starved.”

Sarah felt a wave of anger and sadness, not at John Howell, but at the system that had forced him to choose between his conscience and his survival.

She asked Margaret if she could include the photographs in her research.

Margaret agreed.

“I think people need to see this,” Margaret said.

“I think people need to know what really happened.”

## Chapter 7: The Reckoning

Sarah’s article was published in the spring.

It included all four photographs and detailed the pattern of child labor at McCreary number four.

The response was immediate.

A regional museum in Beckley contacted her about creating an exhibition.

A documentary filmmaker expressed interest in adapting the story, and the local newspaper ran a front-page story with the headline, “Hidden Children: New Research Exposes Illegal Child Labor in WV Coal Mines.”

But not everyone was pleased.

Two months after the article was published, Sarah received an email from a lawyer representing the current corporate successor of the Alagany Coal and Iron Company.

The company, now a division of a much larger energy conglomerate, objected to what it called unsubstantiated allegations and reckless speculation.

The lawyer demanded that Sarah retract her article and apologize for damaging the reputation of a historic West Virginia business.

Sarah forwarded the email to her university’s legal counsel.

The university lawyer wrote back within an hour, “They have no case.

Your research is solid.

Do not retract anything.”

Sarah did not.

Instead, she accepted the museum’s offer and began working on the exhibition.

She contacted Linda Ree, the child labor historian, and William Oaks, the retired archivist.

Together, they assembled a collection of photographs, documents, and oral histories that told the story of child labor in the West Virginia coal fields.

The centerpiece of the exhibition was the 1905 photograph of the two miners and the boy.

The museum printed it large, three feet wide, and mounted it on the wall with a magnifying glass on a stand so visitors could lean in and see the child’s face for themselves.

Beside it, they placed a placard with the boy’s number, 372, and a short paragraph explaining what trappers did and why their work was illegal.

They also displayed the coroner’s reports and the photographs Margaret Howell had provided, and they included excerpts from the United Mine Workers pamphlet and testimonies from miners who had spoken out about child labor.

## Chapter 8: The Names and the Numbers

The exhibition opened in October.

On the first day, more than 200 people attended.

Local news stations covered it.

Descendants of miners came and stood in front of the photographs, some crying, some silent, some angry.

One man, a retired coal miner in his seventies, stood in front of the main photograph for nearly twenty minutes.

Finally, he turned to Sarah and said, “My grandfather worked in those mines.

He told me stories, but I didn’t believe him.

I thought he was exaggerating.

Now I see he wasn’t.”

Three weeks after the exhibition opened, Sarah received a letter from a woman named Ruth Anne Peterson.

She lived in Ohio, but her grandmother had been born in a coal camp near McCreary number four.

Ruth Anne had visited the exhibition and recognized something in one of the photographs Margaret Howell had provided—the boy eating from the lunch pail.

Ruth Anne wrote, “I think that’s my great uncle, Henry Carter.

My grandmother said he died in the mine when he was ten years old.

The company told the family it was an accident.

They paid them $50 and told them not to ask questions.”

Sarah called Ruth Anne and asked if she had any documents.

Ruth Anne said she had her grandmother’s Bible, and inside it, pressed between the pages, was a small photograph of a boy.

She sent Sarah a scan.

It was the same boy.

Sarah added Henry Carter’s name to the exhibition.

She also added the names of the four boys from the coroner’s reports: Thomas Riby, Amos Fletcher, Samuel Kowalski, and the unnamed nine-year-old boy whose body had been recovered from the lower gallery.

She could not identify the boy in the main photograph, the one holding the door prop, the one whose number was 372, but she made sure visitors knew he had existed, that he had worked in the darkness, that he had been made invisible by a company that valued profit over life.

## Chapter 9: Shadows on the Wall

The exhibition ran for six months.

During that time, more than 3,000 people visited.

Teachers brought their students.

Historians came from other states.

Descendants of coal miners stood in front of the photographs and wept.

And the corporate successor of the Alagany Coal and Iron Company never sued.

Sarah returned to her office and filed the photographs in her archive.

She labeled them carefully with dates and names and context.

And she wrote a note on the file folder: evidence of erasure, evidence of resistance, evidence that someone somewhere always knows the truth.

She thought about the photographer who had taken that portrait in September 1905.

He had been hired to create an image of American strength and dignity.

He had posed the miners.

He had adjusted the light.

He had counted down and pressed the shutter.

And he had failed to notice the child.

Or perhaps he had noticed.

Perhaps he had seen the boy standing there and decided to take the photograph anyway.

Perhaps he had known that someone someday would look closely enough to see what the company wanted to hide.

Old photographs are not neutral.

They are arguments.

They are constructed to show power, respectability, and order.

They are meant to tell one story while erasing another.

But sometimes in the gaps and shadows, the erased story survives.

In archives across the country, there are photographs of plantations that do not show the enslaved people who built them.

There are photographs of factories that do not show the children who worked in them.

There are photographs of wealthy families that do not show the servants standing just out of frame.

But if you look closely, if you zoom in on the margins and the backgrounds and the places where the light does not quite reach, you can find them.

The people who were meant to be invisible, the evidence that was meant to be destroyed.

The boy in the photograph at McCreary number four was not supposed to be there.

He was not supposed to exist—not in the official record, not in the company’s story, not in the sanitized history that coal operators wanted the world to see.

But he was there.

And now, more than a century later, his face stares out from the wall of a museum, and visitors stop and lean in and see him.

They see a child who should have been in school.

A child who spent his days in the dark, opening and closing doors so that coal could flow and profits could rise.

A child whose name no one recorded, whose death no one mourned, whose life was measured only by a number pinned to his chest.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load