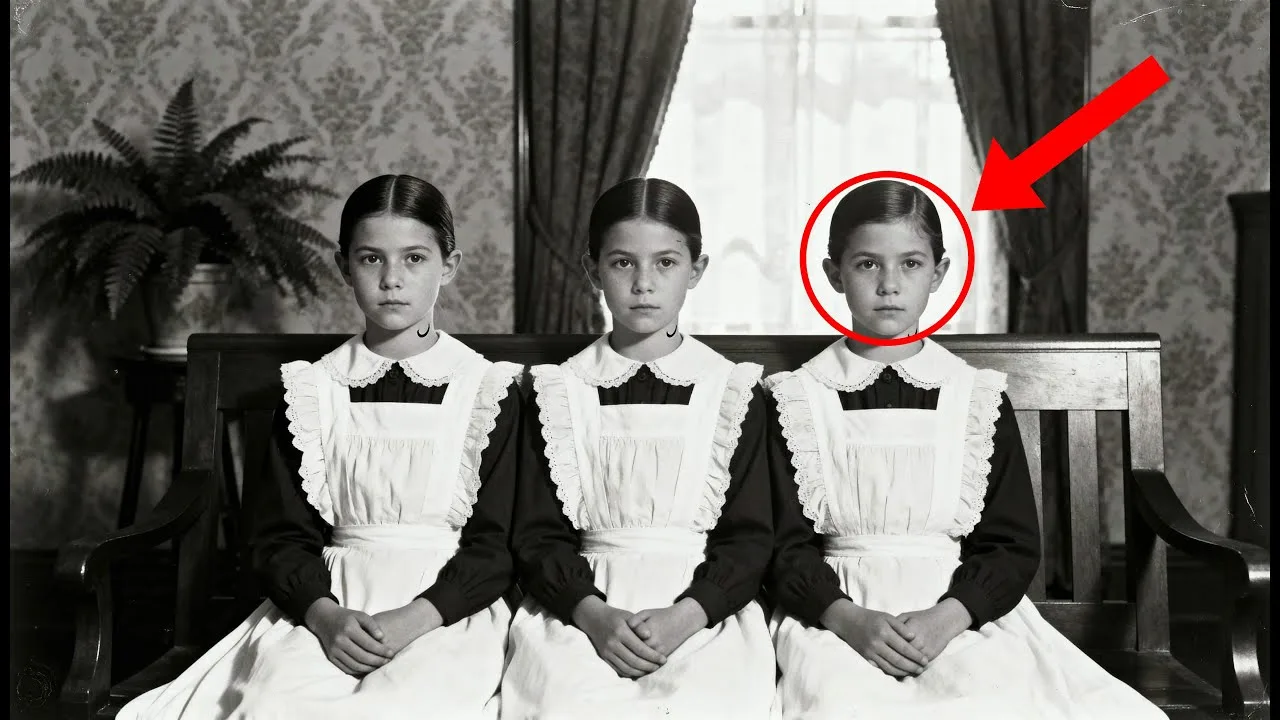

I.The Photograph That Hid a Century of Pain

This 1902 portrait of three orphan girls looks normal—until you see their identical scar.

At first glance, the image is just another staged portrait from a turn-of-the-century charitable institution.

Three girls in matching dresses, hands folded, faces composed, seated on a wooden bench in a formal parlor.

A floral wallpaper behind them, a potted fern to their left.

Their hair is parted in the middle, pulled back severely, their hands folded in their laps, eyes focused just past the camera.

It’s the kind of institutional photograph meant to reassure donors: clean, orderly, grateful children rescued from poverty and prepared for respectable futures.

But one detail refused to let go.

And once you see it, the entire image collapses into something else entirely.

II.

The Scar That Changed Everything

Dr.

Sarah Brennan had worked as an archivist at the Cincinnati Historical Society for eleven years when she first encountered the photograph.

It arrived in a donated collection from the Aldridge family, packed in a leather portfolio with dozens of other images documenting their philanthropic work.

Sarah was cataloging the collection in the society’s climate-controlled processing room on a Tuesday afternoon in March when she pulled the photograph from its sleeve.

She almost moved on—she’d seen hundreds of these images from orphanages, reform schools, industrial training programs, all those Progressive Era institutions that promised to rescue poor children and instead often devoured them.

But something made her look again.

Under her magnifying lamp, the girls’ posture was too stiff, even for that era.

Their shoulders pulled back in a way that suggested discomfort, and their hair, though neatly arranged, seemed positioned to conceal something.

Sarah zoomed her digital scanner to maximum magnification and captured each girl’s neck and upper back.

When she examined the images on her monitor, her stomach tightened.

Just below the hairline at the back of each girl’s neck, barely visible where the hair had shifted, was a mark—small, crescent-shaped, the skin slightly raised and discolored.

A scar.

And not just on one girl.

On all three, in exactly the same location.

This was not just a pretty old photo.

Something here was wrong.

III.

The House of Mercy and the Missing Names

Sarah had spent more than a decade examining historical photographs of vulnerable populations.

She knew how institutions used photography to construct narratives—to show improvement and respectability while hiding the mechanisms of control underneath.

Identical scars on three children in an institutional setting did not happen by accident.

She removed the photograph from its mount and examined the backing.

There in faded brown ink: “Girls of the House of Mercy Industrial Training School, Cincinnati, April 1902.

Photographer: Weaver and Sons Studio.” Below that, in smaller letters: “Ruth, Agnes, Catherine.” No last names.

Just first names and the institutional designation, as if the girls belonged to the House of Mercy rather than to themselves or any family.

Sarah photographed the inscription, then turned to her computer and pulled up the Cincinnati city directories for 1900 to 1905.

Weaver and Sons had a studio on Vine Street, specializing in commercial and institutional photography, advertising their discretion and professionalism.

The House of Mercy Industrial Training School had an address on the west side of the city near the river, listed under charitable organizations “for orphaned and wayward girls.” The donor was Mrs.

Constance Aldridge—the same family name as the donors.

Sarah made a note of that connection and studied the room in the background.

The wallpaper appeared expensive, the fern a Victorian parlor staple meant to soften institutional spaces and make them seem homelike.

But the girls were positioned very deliberately, almost as if instructed exactly where to place their hands, exactly how to hold their heads and eyes.

Sarah had seen that look before in photographs of people who were afraid.

IV.

The Search for the Truth

If she stopped now, if she simply cataloged this photograph with a neutral description and moved on, a story would stay buried.

Three girls with matching scars would remain nameless and their experience invisible.

Sarah texted Dr.

Marcus Webb, a University of Cincinnati historian specializing in Progressive Era child welfare institutions: “Found something disturbing.

Can you meet tomorrow?”

The next morning, Marcus arrived at the historical society carrying a leather satchel and a thermos of coffee.

Sarah had the photograph waiting on the examination table along with printouts of everything she’d found.

Marcus leaned over the image, adjusted his glasses, and was quiet for a long moment.

“House of Mercy,” he said finally.

“I know that place.” He laid out several photocopied documents.

“It was part of that wave of reform institutions that opened in the 1890s, supposedly to rescue poor girls from the streets and train them for domestic service.

But there were complaints.” He tapped a newspaper clipping from 1904.

“Parents tried to get their daughters back and were refused.

A few girls ran away and told stories about harsh discipline, but the institution had powerful backers—the Aldridges, the Tafts, several prominent families.

The complaints went nowhere.”

Sarah pointed to the scars on the monitor.

“All three girls, same location, same shape.

That’s not coincidental.”

Marcus studied the photograph with a magnifying glass.

“No.

That’s deliberate.

Some kind of physical restraint or punishment device that left a consistent mark.

We need to find the institutional records.

If the House of Mercy kept log books or medical files, they might tell us what happened to these girls.”

V.

The Evidence Hidden in Archives

The House of Mercy had closed in 1911, its operations absorbed into a larger city-run children’s home.

Sarah filed a request with the Hamilton County Archives and found a partial set of records—admission logs, financial ledgers, donor correspondence—but the daily disciplinary records and medical files were missing.

Either they had been destroyed or were in private hands.

She searched through old Cincinnati newspapers on microfilm, looking for any mention of the institution beyond the flattering donor appeals.

She found a brief article from 1903 about a state inspector’s visit.

The inspector praised the orderly atmosphere and well-trained inmates, but noted that the institution maintained “strict physical discipline in keeping with modern reformatory science.” No details about what that discipline entailed.

Marcus reached out to Dr.

Patricia Vance, a medical historian at Johns Hopkins who studied institutional abuse in child welfare settings.

When Patricia arrived in Cincinnati three weeks later, she brought a thick binder of research on Progressive Era disciplinary practices.

“Restraint collars,” Patricia said, laying photographs and diagrams across the conference table.

“They were used in several reform schools and training institutions during this period.

Metal collars lined with leather, fitted around the neck, sometimes attached to a wall or bedpost.

They were marketed as humane alternatives to corporal punishment because they didn’t leave visible bruises.

Manufacturers called them ‘training devices’ or ‘corrective posture supports.’ They were meant to force girls to stand or sit in one position for hours to break their will without breaking their skin.”

Sarah felt sick.

“But they did leave marks.”

“Eventually, yes,” Patricia pointed to a medical diagram from 1906.

“Extended use caused pressure sores, nerve damage, and scarring, especially at the back of the neck where the metal edge rubbed against the skin.

The scars were often crescent-shaped because of the collar’s design.”

She looked at the photograph of the three girls.

“If these children have matching scars in that exact location, it’s almost certain they were subjected to restraint collars at some point during their time at the House of Mercy.”

Marcus pulled up an advertisement from a trade journal for institutional suppliers from 1898.

The Humane Restraint Company of Philadelphia.

The ad featured an illustration of a young girl standing perfectly upright with her hands at her sides, a thin collar just visible around her neck.

The copy read: “For the correction of wayward and disobedient inmates, encourages proper posture and docile behavior, no lasting harm.”

“They sold these things openly,” Sarah said.

“They did,” Patricia answered.

“Progressive reformers bought them, convinced they were being modern and scientific.

The language of reform covered a multitude of cruelties.”

VI.

The Ledger and the Code

Sarah returned to the archives with new focus.

She needed to know what had happened to Ruth, Agnes, and Catherine.

She pulled every record she could find related to the House of Mercy.

In the financial ledgers, she found payments to the Humane Restraint Company in 1900, 1901, and 1903.

The items were listed as “corrective equipment,” with no further details, but the amounts matched the wholesale prices Marcus had found.

In the donor correspondence, she found letters from Constance Aldridge to potential contributors.

“Our girls learn discipline, cleanliness, and the domestic arts.

They emerge from our care prepared for respectable service in Christian households.” The letters emphasized order and obedience.

They described the girls as reclaimed and reformed.

There was no mention of collars or restraints or pressure sores, only the language of improvement and salvation.

But in a corner of one ledger, Sarah found something else.

A notation system appeared in the margins next to certain girls’ names: small symbols, circles, crosses, sometimes both.

At first, they seemed random, but when Sarah mapped them against admission dates and infractions listed in the sparse disciplinary notes, a pattern emerged.

Girls marked with crosses had been subjected to posture correction.

Girls marked with circles had been confined for insubordination.

Girls with both marks—like Ruth, Agnes, and Catherine—had experienced extended corrective discipline.

The official narrative was clean and progressive and humane.

The institution called itself a house of mercy, claimed to train orphans and wayward girls for productive lives.

The photographs showed well-dressed children in orderly rooms.

But beneath that surface, the ledgers recorded something else: payments for restraint equipment, coded notations for punishment, and three girls sitting for a portrait with matching scars hidden just below their hairlines.

Their bodies arranged to satisfy donors who wanted to believe their money was doing good.

VII.

The Place, the System, and the Survivors

Sarah needed to understand the full scope of what had happened at the House of Mercy and connect it to the larger systems of control that existed around children deemed unfit or troublesome in this era.

She drove to the west side of Cincinnati to the neighborhood where the institution had once stood.

The building was gone, replaced by a small park with a community center.

But the site held echoes.

Sarah walked the perimeter with Marcus and Patricia, consulting old maps and photographs.

The House of Mercy had been a three-story brick structure with barred windows on the upper floors.

The girls slept in dormitories on the third floor, worked in laundry and sewing rooms on the second, and received instruction in ground-floor classrooms.

The parlor, where the photograph had been taken, was at the front of the building, designed to impress visitors.

They visited the Hamilton County Courthouse and requested access to any legal filings related to the institution.

There, in a box of unsorted papers from the early 1900s, Sarah found a complaint filed in 1904 by a woman named Margaret O’Conor, attempting to regain custody of her daughter Catherine, aged 13, who had been placed at the House of Mercy after Margaret’s husband died and she fell into temporary poverty.

The complaint described Catherine’s condition when Margaret finally saw her after eight months: thin, fearful, and marked about the neck with injuries she would not explain.

The court denied the complaint.

The judge ruled that Catherine was receiving proper care and that Margaret, as an unwed mother without means, was unfit to resume custody.

Catherine remained at the House of Mercy for another three years.

Patricia helped Sarah trace the broader context.

Reform schools and industrial training institutions of this era operated in a gray zone between charity and incarceration.

They received public funding and private donations, but answered to no one.

Parents, especially poor parents, had almost no legal standing to challenge institutional decisions.

Girls were committed for vague offenses like stubbornness or “moral danger.” Once inside, they had no advocates.

The institutions claimed to rehabilitate, but in practice, they trained girls for a lifetime of servitude, breaking their spirits with discipline that would have been recognized as torture if applied to animals.

The restraint collar was just one tool among many: isolation cells, cold water treatments, forced labor, starvation rations.

But the collar was particularly insidious because it left girls awake and aware, unable to move, sometimes for eight or ten hours at a stretch.

It was meant to teach obedience through exhaustion and pain, to make the body itself an instrument of submission.

Sarah found an account from a former inmate of a similar institution in New York recorded in a 1908 social work report.

The woman, confined as a girl in 1902, described the experience: “They put the collar on at night if you had talked back or refused work.

You stood in the hallway with your neck fixed to the wall and you could not sit or lie down.

By morning, you could not feel your arms and the skin at the back of your neck was raw.

They said it was for our own good to teach us proper behavior.”

The photograph Sarah had found was taken in April 1902, likely just after Ruth, Agnes, and Catherine had been subjected to this discipline.

Their scars were still fresh enough to be visible despite attempts to conceal them with carefully arranged hair.

The photograph was meant for the institution’s annual report, sent to donors as proof of successful reform.

“Look at these well-behaved girls,” the image said.

“See how orderly and clean and grateful they are.

Your money has transformed them from wayward creatures into respectable future servants.”

But the scars told a different story.

They testified to the violence required to produce that appearance of docility.

They marked the girls as survivors of a system that used the language of mercy to justify cruelty.

VIII.

Confronting the Past

Bringing this truth into public view meant confronting the descendants of the institution’s founders and the local historical establishment that had for more than a century told a sanitized version of Progressive Era reform.

Sarah prepared a formal presentation for the Cincinnati Historical Society’s collections committee, scheduled for a Tuesday evening in October.

The committee consisted of board members, major donors, and community representatives.

Several had ancestors who had supported the House of Mercy.

The Aldridge family still had two members on the board.

Sarah set up her presentation in the society’s conference room.

She projected the photograph of the three girls on the screen, then advanced to the magnified images showing the scars.

She displayed the financial ledgers, the legal complaints, the testimonies from survivors of similar institutions, and information about restraint collars and other disciplinary devices.

She laid it out carefully, building the case piece by piece.

When she finished, the room was silent for a long moment.

Then Thomas Aldridge, a retired banker in his seventies, cleared his throat.

“This is a very serious accusation.

My great-grandmother, Constance Aldridge, founded the House of Mercy out of genuine concern for vulnerable girls.

She was a progressive reformer, a woman ahead of her time.

To suggest that she presided over an institution that tortured children is frankly offensive.”

Sarah kept her voice steady.

“I’m not making accusations, Mr.

Aldridge.

I’m presenting documentary evidence.

The restraint equipment purchases are in the financial records.

The scars are visible in the photograph.

The legal complaints exist.

This is what happened.”

Margaret Voss, the board president, leaned forward.

“But we need to think about context, Sarah.

Progressive Era reformers believed they were helping these children.

The methods may seem harsh to us now, but they were considered scientific at the time.

We can’t judge the past by present standards.”

“I’m not judging,” Sarah said.

“I’m telling the truth about what happened to these girls—Ruth, Agnes, and Catherine.

They were subjected to painful restraints that left permanent scars.

That photograph was staged to hide that abuse and solicit more donations.

Those are facts, not interpretations.”

Patricia spoke up from her seat in the back.

“If I may, I’ve studied dozens of these institutions.

The abuse wasn’t accidental or incidental.

It was systematic, and it wasn’t universal.

Plenty of progressive reformers rejected these methods.

Even at the time, there were public debates about the ethics of restraint devices.

The people who used them knew they were causing harm.

They just didn’t care because the victims were poor children with no power.”

Thomas Aldridge shook his head.

“This is going to damage the society’s reputation.

We have donors who remember the House of Mercy fondly.

Their families supported it for decades.

If we start calling it an abusive institution, we’ll lose their support.”

“Then we lose it,” Sarah said.

“But we don’t hide the truth to protect donors.

These girls deserve to have their story told accurately.”

The meeting lasted another two hours.

Arguments about framing, about balance, about whether the evidence was really conclusive or just suggestive.

Some committee members were genuinely disturbed and wanted to tell the story honestly.

Others worried about controversy, funding, and tarnishing the memory of prominent families.

Margaret Voss, to her credit, kept the conversation focused on the mission of the historical society: to preserve and present the city’s history truthfully, even when that history was uncomfortable.

In the end, the committee voted narrowly to approve an exhibition centered on the photograph and the larger story of Progressive Era institutional abuse.

But there were conditions.

The exhibition had to include multiple perspectives.

It had to acknowledge the reformers’ stated intentions alongside the documented harm.

It had to be framed as an educational opportunity, not an accusation.

Sarah agreed, though she knew she would have to fight to keep the exhibition from being softened into meaninglessness.

IX.

Restoring the Girls’ Stories

Over the following months, Sarah and Marcus worked with a team of designers and educators to build the exhibition.

They called it *Hidden in Plain Sight: Photography and Power in Progressive Era Reform*.

The photograph of Ruth, Agnes, and Catherine was the centerpiece, displayed large on one wall with magnified details showing the scars.

Beside it, they placed the financial records, the legal complaints, testimonies from survivors of similar institutions, and information about restraint collars and other disciplinary devices.

But they also wanted to center the girls themselves—to restore some sense of their humanity and agency.

Sarah spent weeks tracking down what had happened to them after they left the House of Mercy.

Ruth appeared in the 1910 census, working as a domestic servant in a household on the east side of Cincinnati.

She was listed as 20 years old, no family, living in the servants’ quarters.

Sarah could find no further trace of her after that.

Agnes turned up in the records of a tuberculosis sanatorium in 1908.

She died there in 1909, age 18.

The death certificate listed her occupation as domestic and noted no family to notify.

Catherine, Margaret O’Conor’s daughter, had a different trajectory.

Sarah found her in the records of a small African Methodist Episcopal church on the west side, the same church that had fought to help Margaret regain custody.

Though the court had denied Margaret’s petition, the church community had not given up.

In 1907, when Catherine turned 16 and aged out of the institution’s control, members of the church met her at the door of the House of Mercy and brought her to Margaret.

Church records showed Catherine married in 1912, had three children, and lived until 1956.

Sarah contacted Catherine’s granddaughter, Denise Williams, who still lived in Cincinnati.

Denise had heard stories about her grandmother’s time in the institution, but the family had always spoken of it in vague terms as something painful that was better left in the past.

When Sarah showed her the photograph and explained what the scars meant, Denise wept.

“She never talked about it directly,” Denise said, “but I remember her rubbing the back of her neck sometimes, especially when she was stressed.

And she was always gentle with us, never punished us harshly.

She would say, ‘Children need love, not breaking.’”

Denise agreed to contribute to the exhibition, sharing her grandmother’s story and emphasizing the role the church community had played in Catherine’s survival and recovery.

X.

The Exhibition and Its Impact

The exhibition opened in March 2023, more than a year after Sarah had first encountered the photograph.

The response was intense.

Local media covered it extensively.

Some praised the historical society for confronting difficult truths.

Others criticized it for tarnishing the memory of progressive reformers.

The Aldridge family issued a statement expressing regret for any harm done at the House of Mercy while defending their ancestors’ good intentions.

But the most meaningful responses came from visitors who saw their own family stories reflected in the exhibition.

Descendants of other girls who had been confined in reform institutions, people whose grandmothers and great-grandmothers had been marked by similar systems of control.

They left notes in the exhibition’s comment books thanking the historical society for finally acknowledging what had happened.

One woman wrote, “My grandmother was in a place like this in Kentucky.

She had the same scar.

I never knew what it meant until now.

Thank you for telling the truth.”

Sarah stood in the exhibition space one afternoon a few weeks after opening, watching visitors move through the displays.

A group of college students clustered around the photograph of Ruth, Agnes, and Catherine, reading the accompanying text carefully.

A middle-aged couple studied the financial ledgers in silence.

A grandmother explained to her grandchildren what a restraint collar was and why it was wrong.

Marcus joined her.

“You did good work here,” he said quietly.

Sarah nodded, but felt the heaviness that always came with this kind of research.

“Three girls,” she said.

Two of them dead young, one of them rescued by a community that refused to give up on her.

And for a hundred years, this photograph was just filed away as evidence of successful charity.

“Not anymore,” Marcus said.

The exhibition ran for six months.

It traveled to two other cities afterward, each time sparking similar conversations about institutional abuse, Progressive Era reform, and the ways photography had been used to construct false narratives about care and rehabilitation.

Sarah published an article in a historical journal detailing her research, which became a foundation for further scholarship on disciplinary practices in child welfare institutions.

XI.

The Photograph’s Legacy

Beyond the exhibitions and the publications, what stayed with Sarah was simpler and more personal.

She had given Ruth, Agnes, and Catherine their names back.

She had made visible what the photograph had tried to hide.

She had insisted that the scars mattered, that they testified to real pain inflicted on real children in the name of reform and mercy.

Old photographs are not neutral documents.

They are not simply windows into the past.

They are constructed images, staged and framed to tell particular stories, to serve particular purposes.

The portrait of three girls in matching dresses sitting on a bench in a formal parlor was created to reassure wealthy donors that their charitable contributions were transforming poor and wayward children into respectable future servants.

It was propaganda designed to conceal the violence required to produce that appearance of docility and order.

But photographs also sometimes inadvertently preserve evidence that complicates or contradicts their intended message.

A strand of hair shifts during a long exposure.

A child cannot quite control her expression.

And suddenly, if you know how to look, if you are willing to look, the image reveals what it was meant to hide.

There are thousands of photographs like this one in archives and museums and family collections across the country.

Images of orphanages and reform schools and industrial training programs, all showing clean children in orderly rooms, all testifying to the success of progressive charity.

How many of them hide matching scars, coded ledgers, stories of restraint and breaking and pain? How many girls like Ruth and Agnes and Catherine are frozen in those images, their suffering concealed beneath careful staging and sanitized captions?

Rereading these photographs is not about condemning the past or judging our ancestors by contemporary standards.

It is about restoring truth and agency to people who had neither when the camera clicked.

It is about insisting that their pain mattered, that their resistance mattered, that their survival mattered.

It is about recognizing that the language of mercy and reform and progress often covered systems of extraordinary cruelty, and that the evidence of that cruelty is still there, visible in the archives, if we are willing to see it.

The photograph of Ruth, Agnes, and Catherine now hangs in the Cincinnati Historical Society’s permanent collection, displayed with full context about what happened at the House of Mercy and what the scars on their necks represent.

Visitors can see the girls as they were meant to be seen—not as symbols of successful charity, but as children who endured institutionalized abuse and whose story demands to be told honestly.

Catherine survived, built a family, passed down a legacy of gentleness that her granddaughter still honors.

Ruth and Agnes vanished into the historical record, their lives cut short.

But they are no longer invisible.

Every photograph of institutional life from this era deserves that same scrutiny, that same commitment to seeing what is really there beneath the surface of respectability.

Because the truth is always in the details—in the hands folded too tightly, in the eyes that look past the camera instead of at it, and in the small crescent scars hidden just below the hairline, testifying to violence that the image was designed to conceal.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load