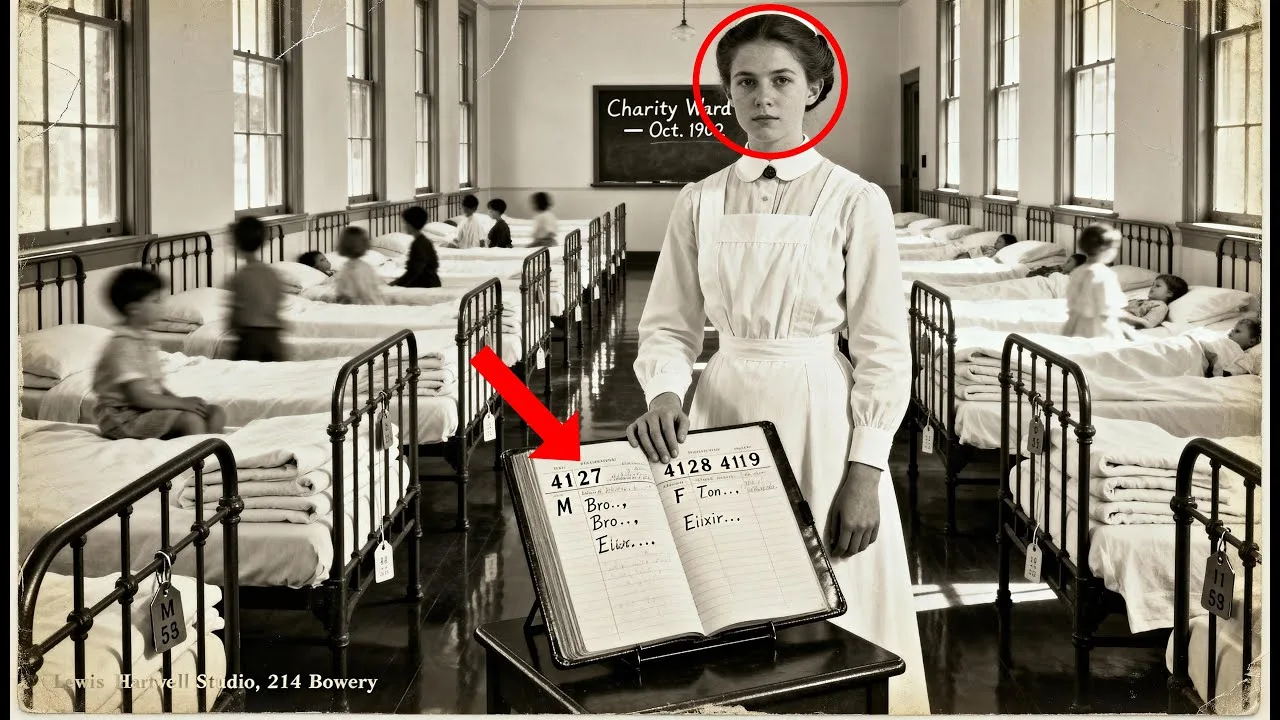

This 1902 Portrait of a Nurse Looks Noble Until You Notice the Ledger Beside Her

This 1902 portrait of a nurse looks noble until you notice the ledger beside her.

It hung for decades in the hallway of a medical museum in Manhattan.

A symbol of compassionate care during the progressive era.

The image showed dedication, professionalism, and the quiet heroism of early nursing until someone looked closer at what was written on that open page.

Dr.

Sarah Chen is a medical historian specializing in hospital archives.

She has spent 17 years cataloging thousands of images from New York’s early healthcare institutions.

In the summer of 2019, she was reorganizing the photographic collection at the Museum of Medical History when she pulled down a framed portrait that had been hanging in the same spot since the museum opened in 1954.

The photograph is formally composed.

A young woman in a crisp white uniform stands beside an iron bed frame in what appears to be a ward.

Her expression is serious but not unkind.

Her hand rests on a leather-bound notebook that lies open on a small table.

Behind her, partially visible in the soft focus, are rows of beds.

The photographers’s stamp on the lower right reads Hartwell Studio 214 Bowery.

Chen had seen hundreds of similar images, nurses photographed for annual reports, fundraising appeals, and commemorative albums.

But when she removed the portrait from its frame to check for any inscription on the reverse, she noticed something that made her pause.

She carried the photograph to her desk and switched on a high-powered magnifying lamp.

The notebook in the image was positioned at just the right angle for the camera to capture part of the visible page.

Chen could make out a column of numbers, 4127, 4128, 4129.

Below them, partial words she could not quite read.

She increased the magnification.

The handwriting was neat, methodical.

These were not random notes.

They were entries in some kind of registry.

Chen photographed the detail with her phone and uploaded it to her computer.

She adjusted the contrast and sharpened the image.

Now she could read more.

Next to each number was a single letter, either M or F, and beside those fragments of words, bro and ton, and what might have been elixir.

She sat back in her chair.

In her years working with medical archives, Chen had developed an instinct for when an image was hiding something.

This was not just a pretty old photo.

Something here was wrong.

Chen has a doctorate in the history of medicine from Colombia.

Before that, she worked as an archivist at Belleview Hospital where she processed records dating back to the 1820s.

She knows how to read institutional documents, how to trace the evolution of medical practices through ledgers and logs and patient registries.

She has seen the bureaucratic language that hospitals use to obscure unpleasant truths.

This photograph bothered her in a way she could not immediately articulate.

She carefully removed the backing board from the frame.

Sometimes photographers or family members left notes.

On the reverse of the print, written in faded pencil, was a brief inscription.

Miss Adelaide Morrison, St.

Vincent’s Charity Ward, October 1902.

Chen turned the photograph over again and studied the nurse’s face.

Adelaide Morrison looked to be in her mid20s.

Her uniform suggested she had completed formal training, which was still relatively uncommon in 1902.

Most nurses at that time learned on the job.

But Morrison’s bearing and dress indicated she had attended one of the new nursing schools that were beginning to establish professional standards.

But it was the notebook that would not let Chen go.

She enlarged the image on her screen again.

Those numbers 4127 through 4129 were too specific to be ward numbers or bed assignments.

They looked like patient identification codes, and the fragments of words beside them suggested some kind of treatment or medication.

She felt the familiar weight of ethical obligation settling onto her shoulders.

If she stopped here, if she filed this photograph back into the collection without investigating further, a story would remain buried.

And Chen had learned long ago that buried stories in medical archives almost always belong to people who had already been denied a voice.

Chen began with the obvious leads.

She searched the museum’s database for any other photographs from Saint Vincent’s Hospital.

She found three, one showing the exterior of the building on West 11th Street, one of a surgical theater, and one group portrait of the nursing staff from 1899.

None showed Adelaide Morrison.

Next, she pulled the 1902 city directory.

St.

Vincence was listed as a Catholic hospital founded in 1849, primarily serving the poor and immigrant communities of Greenwich Village and the Lower East Side.

The hospital was run by the Sisters of Charity and relied heavily on donations from wealthy patrons.

Chen then turned to newspaper archives.

She found several articles praising Saint Vincent’s charitable work.

In one piece from the New York Tribune in January 1903, the hospital was lauded for bringing modern medical science to those who would otherwise have no access to treatment.

She searched for Adelaide Morrison in census records and found a likely match, Adelaide R.

Morrison, age 24, occupation listed as trained nurse, living in a boarding house on Christopher Street in 1900.

By 1910, she had married and was no longer working in hospitals.

But the patient numbers in the ledger kept nagging at Chen.

She contacted Dr.

Marcus Webb, a colleague who specializes in the history of pharmaceutical development and medical ethics.

Webb teaches at NYU and has published extensively on unregulated drug trials in the early 20th century.

When Chen sent him the enhanced image of the notebook page, Webb called her within an hour.

“Where did you find this?” he asked.

“A portrait at the museum,” Chen said.

Why those numbers? Web said, “I’ve seen that sequence before in a set of pharmaceutical company records I reviewed last year.

They match a patient coding system used by Brontley Chemical Works.” Chen felt her pulse quicken.

Brontly Chemical? What were they doing at Saint Vincent’s? That’s what we need to find out, Webb said.

Over the following weeks, Chen and Webb began pulling together a picture that grew darker with each new document.

They started with Brontley Chemical Works, a pharmaceutical manufacturer that had been founded in Brooklyn in 1887.

The company specialized in patent medicines and tonics, the largely unregulated remedies that dominated American healthcare before the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906.

In the New York Public Libraryies business archives, they found promotional materials from Brontley Chemical.

The company advertised products with names like Brontley’s Vital Tonic and Brontley’s Elixir for nervous dability.

The advertisements made sweeping claims.

These tonics could cure everything from consumption to kidney failure to female complaints.

But it was in the records of a later lawsuit that Chen and Web found what they were looking for.

In 1909, a group of patients from a hospital in Philadelphia sued Brontley Chemical, claiming they had been given experimental formulations without their knowledge or consent.

The case was settled quietly, and Brontley agreed to cease operations in Pennsylvania.

The settlement documents, however, included depositions that mentioned earlier trials conducted at partner institutions in New York.

Chen requested access to the hospital’s internal archives which were held separately at the Catholic Arch Dascese of New York.

It took 6 weeks to get permission.

When she finally sat down in the archive reading room, she was handed three boxes of Saint Vincent’s administrative records from 19 to 1905.

In the second box, she found it.

A contract dated March 1901 between St.

Vincent’s Hospital and Brontley Chemical Works.

The agreement stated that Brontley would provide donated medicines to the hospital’s charity ward in exchange for observational documentation of patient outcomes.

There was no mention of informing patients.

There was no discussion of consent.

The contract specified that Brontley representatives would visit monthly to review patient registries and that the hospital would maintain detailed records using a numbering system provided by the company.

Chen photographed every page.

Then she kept searching.

In the third box, she found a leatherbound ledger marked Charity Ward Registry 1902.

She opened it carefully.

The pages were filled with entries in neat handwriting.

Each entry included a patient number, name, and age, diagnosis, and treatment administered.

Starting in April 1902, the treatments changed.

Instead of standard medicines like quinine or morphine, the ledger listed Brontly Tonic A and Brontly Tonic B and Brontly Experimental Elixir.

The patient number started at 401 and continued sequentially.

Chen turned the pages, her hands trembling slightly.

She reached October 1902.

Patients 4127, 4128, and 4129.

Three women, ages 19, 34, and 42, all diagnosed with general dability.

All given Brontly Tonic B, and beside each entry, in a different hand, a note, deceased, Nova 2, 1902.

Chen sat in the archive reading room for a long time, staring at those three entries.

Then she turned to the rest of October and November.

There were 47 patients treated with Brontley formulations in those two months.

12 of them died.

She compared the mortality rate to earlier months in the ledger before the Brontley contract.

In a typical month, the charity ward recorded two or three deaths, usually from advanced tuberculosis or typhoid.

But in October and November 1902, after the introduction of Brontley’s experimental tonics, deaths spiked dramatically.

Chen contacted Webb again.

Together, they began mapping out the full scope of what they were uncovering.

Web found records showing that Brontley Chemical had similar partnerships with at least four other charity hospitals in New York and New Jersey.

The company was using poor patients as unwitting test subjects, refining their formulations through trial and error and then marketing the successful tonics to middle class consumers who could afford to pay.

The patients in these trials had no idea what was happening to them.

They came to charity wards because they were poor, often recent immigrants who spoke little English.

They were sick, desperate, and trusting.

When a nurse in a white uniform handed them a bottle of tonic and told them it would help, they had no reason to question it.

But what Chen found most chilling was the realization that Adelaide Morrison, the nurse in the photograph, had almost certainly known what was happening.

That open ledger beside her was not a prop.

It was her record book.

Those patient numbers visible on the page were people she had dosed with experimental medicines.

The photograph was not taken to document compassionate care.

It was staged to show Brontley’s pharmaceutical investors that the trials were being conducted properly, that the documentation was thorough and professional.

Chen and Web traveled to the former site of Saint Vincent’s Hospital, which had closed and moved to a different location decades earlier.

The original building was now condominiums.

They walked the surrounding neighborhood trying to imagine what it had looked like in 1902.

Crowded tenementss, pushcart vendors, streets full of Yiddish and Italian and Irish accents.

This was a community of people working brutal hours in factories and sweat shops, living in cramped apartments without indoor plumbing, vulnerable to every disease that swept through the overcrowded city.

These were the people Saint Vincent’s claimed to serve.

And these were the people Brontley Chemical had quietly exploited.

Webb introduced Chen to Dr.

Ammani Carter, a bioethicist at Mount Si, who studies the history of medical experimentation on marginalized populations.

Carter had written extensively about post civil war medical abuses, the Tuskegee syphilis study, and the exploitation of incarcerated people in drug trials.

“What you’re describing is consistent with a widespread pattern,” Carter said when they met in her office.

Before the establishment of informed consent protocols, medical professionals routinely viewed poor patients and patients of color as resources to be used.

Charity was never just charity.

It was always transactional.

Carter helped them understand the legal and ethical framework of 1902.

There were no federal regulations governing human experimentation.

The American Medical Association had issued voluntary ethical guidelines in 1847, but they were vague and rarely enforced.

Individual doctors and hospitals operated with enormous autonomy.

If a pharmaceutical company wanted to test a new formulation, all they needed was a willing physician and access to patients who had no power to refuse.

The people in that ward had no meaningful choice, Carter explained.

If they wanted medical care, they had to accept whatever treatment was offered.

Refusal meant being turned away.

And for most of them, being turned away meant dying in the street.

Chen asked the question that had been troubling her most.

Did Adelaide Morrison understand what she was participating in? Carter considered this carefully.

Nurses in that era were trained to follow doctor’s orders without question.

But a nurse keeping detailed records like the ones you found, she knew this was more than routine treatment.

Whether she understood the ethical implications, whether she felt complicit or thought she was helping advance medical science, we can’t know for certain.

But she was not ignorant.

The photograph took on new meaning.

Adelaide Morrison’s serious expression, her hand resting on that open ledger, her professional bearing.

This was not a candid moment.

This was a performance.

A performance for someone.

Perhaps Brontly investors or hospital administrators who wanted proof that their experimental system was functioning smoothly.

Chen and Webb now had to decide what to do with what they had found.

The Museum of Medical History, where the photograph hung, was a respected institution.

But it was also cautious about controversy.

Its board included descendants of prominent medical families and donors with financial stakes in pharmaceutical companies.

Chen scheduled a meeting with the museum’s director, Dr.

Patricia Hollis.

She brought copies of all the documents she had found, the Brontley contract, the patient ledger, the lawsuit depositions, and the enhanced photograph showing the visible patient numbers.

Hollis studied the materials in silence.

Finally, she looked up.

This is disturbing, she said.

But I’m not sure what you want me to do about it.

We can’t rewrite history.

We’re not rewriting it, Chen said.

We’re reading it correctly for the first time.

But this photograph has been part of our collection for 70 years.

Hollis said, “It’s been in publications about the history of nursing.

Families have come here specifically to see images of early medical professionals who look like Adelaide Morrison.

If we suddenly claim she was part of some unethical experiment, were going to face backlash.

Webb spoke up.

The evidence is clear.

Brontly Chemical used charity patients as test subjects.

Saint Vincent’s Hospital enabled it and this nurse documented it.

Those are facts, not interpretations.

Facts that could damage our reputation.

Hollis said facts that could cost us donors.

The meeting went on for 2 hours.

Hollis was not hostile, but she was deeply concerned about the implications.

The museum was planning a major fundraising campaign.

Several board members had connections to pharmaceutical companies.

Mounting an exhibition that exposed historical medical abuse might be seen as an attack on the industry itself.

Chen understood the politics, but she would not back down.

If we don’t tell this story, we’re complicit in erasing it.

Those patients in that ward deserve to have their exploitation acknowledged.

Hollis asked for time to consult with the board.

Over the following months, Chen and Webb continued their research.

While waiting for the museum’s decision, they found records showing that after the 1909 lawsuit, Brontley Chemical had quietly dissolved.

Its assets were purchased by a larger pharmaceutical firm, which eventually became part of one of today’s major drug manufacturers.

They also found death certificates.

Maria Zeleleski, age 34, patient number 4128, died November 2nd, 1902.

Cause of death listed as heart failure.

But the symptoms described in the hospital ledger suggested something else.

Rapid pulse, convulsions, respiratory distress, classic signs of poisoning or toxic reaction.

Chen tracked down Maria Zeleleski’s descendants through genealogy databases.

She found a great grandson, Thomas Kowalsski, living in New Jersey.

“When she called him and explained what she had discovered, there was a long silence on the line.” “I knew my great-grandmother died young,” Kowalsski said finally.

“But my family always said it was because she was fragile, that she just couldn’t survive here after coming from Poland.” “She wasn’t fragile,” Chen said gently.

“She was experimented on.” In December 2019, the Museum of Medical Histories board voted to approve a new temporary exhibition titled Charity and Complicity: Hidden Histories of Medical Experimentation.

The photograph of Adelaide Morrison would be the centerpiece, but it would be presented very differently than before.

The exhibition opened in February 2020.

Chen worked with a team of curators to design panels that told the full story.

The photograph was enlarged and mounted beside a reproduction of the patient ledger.

Visitors could see the patient numbers visible in Morrison’s notebook and then read the corresponding entries from the hospital registry.

They could see the names Maria Zeleleski, Dorothy Chen, Kathleen O’Brien.

They could see the treatments Brontly Tonic B, Brontley experimental elixir, and they could see the outcomes deceased.

Deceased deceased.

The exhibition included testimony from the 1909 lawsuit.

One patient, a man named Joseph Romano, described being given a medicine that made him violently ill.

“I thought the hospital was trying to help me,” he told the court.

“I didn’t know I was a test animal.” “Thomas Kowalsski attended the opening.

He stood in front of the enlarged photograph for a long time, staring at Adelaide Morrison’s hand resting on that ledger.

“She wrote down my great-g grandandmother’s death,” he said quietly.

“She watched her die, and she just wrote it down.” But the exhibition also included context about nursing in 1902.

A panel explained the limited autonomy nurses had, their obligation to follow physician orders, the professional pressures they faced.

It did not excuse Morrison’s participation, but it situated her within a system that was designed to exploit the vulnerable, and silence those who might object.

The exhibition drew significant media attention.

Several newspapers ran stories about the forgotten victims of early pharmaceutical testing.

A documentary filmmaker contacted Chen about developing a fulllength film.

And crucially, descendants of other patients began coming forward.

A woman named Lisa Martinez brought in a photograph of her great uncle who had died at age 23 in a Manhattan charity hospital in 1903.

She had always been told he died of pneumonia, but after seeing the exhibition, she requested his hospital records.

He had been patient number 4892 in a Brontley trial.

An elderly man named Robert Hughes contacted the museum to say his grandmother had been a patient at St.

Vincent’s in 1902.

She survived, but she told her children that the hospital had given her something that made her so sick she thought she would die.

“They experimented on me,” she had said.

Her children thought she was confused, traumatized by poverty and illness.

Now they understood she had been telling the truth.

Not everyone responded positively.

A descendant of one of Saint Vincent’s founding physicians wrote an angry letter accusing the museum of slandering the memory of dedicated healers.

A pharmaceutical industry group issued a statement emphasizing how much medical ethics had evolved since 1902, implicitly suggesting the exhibition was unfairly judging the past by present standards.

But Chen and her colleagues had anticipated this.

They had built the exhibition carefully using only verifiable evidence.

They had consulted with bioethicists and historians and they had centered the voices of the exploited whenever possible.

The final panel of the exhibition featured a quote from Joseph Romano’s 1909 testimony.

I came to that hospital because I was sick and poor.

They told me they would help me.

I trusted them because I had no choice.

When I learned the truth, I felt like less than human.

I am not medicine.

I am a man.

The exhibition ran for 6 months.

When it closed, the photograph of Adelaide Morrison was moved to a new permanent display about medical ethics.

The label now read, “Nurse Adelaide Morrison, St.

Vincent’s Hospital Charity Ward, October 1902.” This photograph was staged to document pharmaceutical trials conducted on patients without their knowledge or consent.

The ledger visible beside Morrison contains patient numbers later identified as participants in experimental drug tests that resulted in multiple deaths.

Chen wrote an academic article about the case that was published in the journal of medical humanities.

Webb incorporated the findings into a revised edition of his book on pharmaceutical history.

Dr.

Carter used the case as a teaching example in her bioeththics courses.

But perhaps most importantly, the story prompted other medical archives to begin reviewing their own collections with more critical eyes.

A curator in Philadelphia found similar photographs from charity hospitals in the 1890s.

An archavist in Chicago discovered contracts between hospitals and chemical manufacturers.

The pattern Chen had uncovered was not isolated to Saint Vincent or to Brontly Chemical.

It was systemic.

Old photographs are not neutral.

They were composed, staged, and preserved for reasons.

And often those reasons had everything to do with power.

The image of Adelaide Morrison was meant to project competence and compassion, to reassure donors and investors that charity work was being conducted properly.

It was meant to be evidence of benevolence.

But photographs can betray their makers.

A ledger positioned at the wrong angle, numbers visible for just a moment when the shutter clicked and the whole carefully constructed narrative begins to crack.

What was meant to prove virtue becomes proof of exploitation.

There are thousands of images like this in archives and museums.

Portraits of smiling factory owners standing among child workers.

Group photographs of plantation households with enslaved people arranged in the background.

medical professionals posing beside patients who could not consent to being photographed or treated.

These images are still used in textbooks and documentaries, still hung in hallways and exhibitions, still deployed to tell stories about progress and care.

And in most of them, if you look closely enough, there is a detail that reveals what the photographer wanted to hide.

A chain that should not be there.

A posture that suggests coercion rather than cooperation.

a ledger with the wrong kind of numbers.

Chen keeps a copy of the Morrison photograph on her office wall, not as decoration, but as a reminder.

Every time she opens an archive box, every time she lifts an old photograph into the light, she asks herself the same question.

What am I not seeing? What violence is hiding in plain sight? Because once you learn to read these images differently, you cannot stop seeing.

The nurse’s hand on the ledger is not gentle.

It is recording.

The patient numbers are not administrative details.

They are people stripped of names.

The professional bearing is not compassion.

It is complicity.

And somewhere in an archive right now, there is another photograph waiting.

Another detail that someone has not yet noticed.

Another story of people who were told they were being helped when they were really being used.

The camera captured it all.

We just have to be willing to

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load