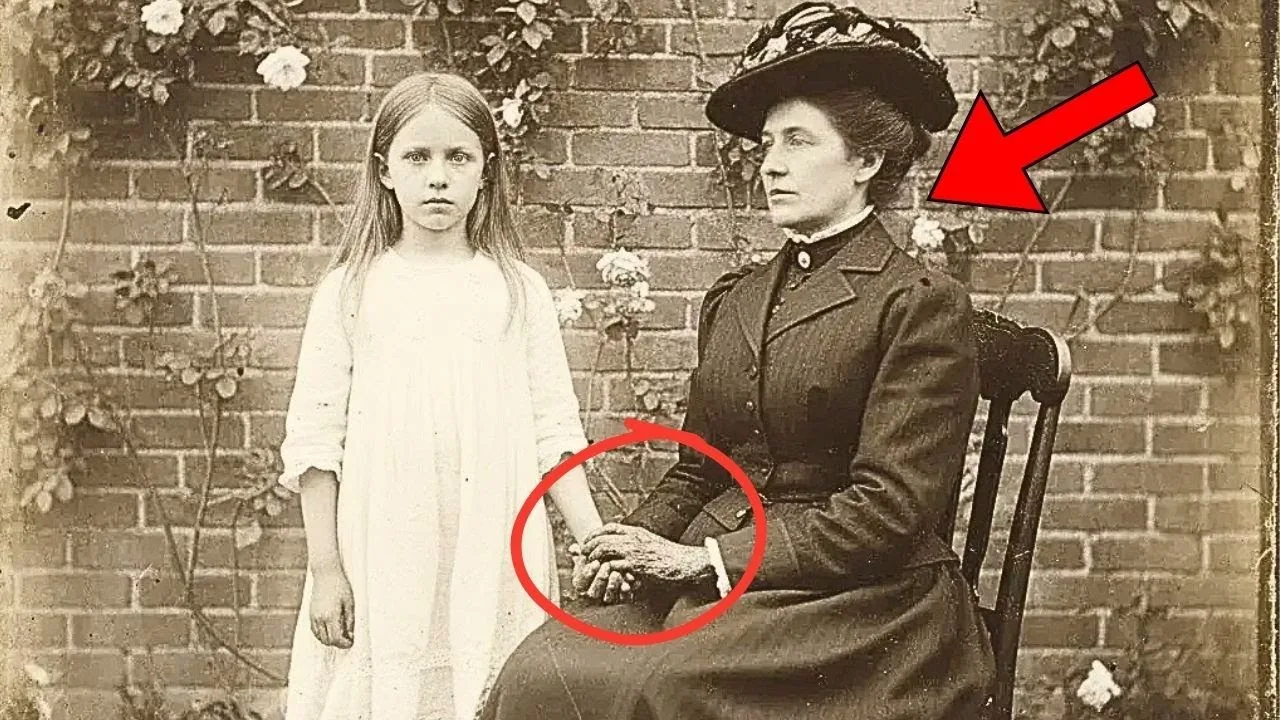

I.The Photograph That Froze a Nightmare

When digital restoration expert Dr.

Sarah Chen magnified a faded 1899 photograph to 4,000% in 2019, she stopped breathing.

For 120 years, everyone who saw this image believed it showed a woman and a young girl holding hands in a garden—a mother and daughter, a touching Victorian portrait.

But the high-resolution scan revealed something so disturbing that Sarah immediately called the police archives.

The woman in this photograph had been dead for three weeks when the picture was taken.

What you’re looking at isn’t a family portrait—it’s evidence of one of the most haunting crimes in Victorian England.

And the girl holding that hand had no idea.

Before we reveal what restoration uncovered, subscribe now—because once you see what’s really in this photograph, you’ll never look at old pictures the same way again.

II.The Smell That Wouldn’t Leave

The neighbors noticed the smell first.

It was August 15, 1899, in London’s Whitechapel district, a neighborhood still infamous for the Jack the Ripper murders of 11 years earlier.

The summer heat was oppressive, turning the cramped tenements into brick ovens.

But the stench from the ground floor flat at 47 Thrall Street was different.

Sweet and rotten, like overripe fruit—except beneath that was something far worse: the unmistakable odor of decomposing flesh.

Mrs.

Eleanor Blackwood, who lived upstairs, finally went to the police.

“It’s been three weeks,” she told Constable William Morris.

“Three weeks of that terrible smell, and I haven’t seen Miss Hartley come out once.

And the little girl, Emma—I hear her talking in there, but she never comes out.

Something’s very wrong.”

Constable Morris, with Sergeant James Peton, arrived at 47 Thrall Street at 10 a.m.

They knocked.

No answer.

They knocked harder.

“Police! Open up!” They heard movement inside—small footsteps, then a child’s voice, high and uncertain.

“Mama says we can’t open the door.”

“Where is your mama, sweetheart?” Peton called, trying to keep his voice gentle despite the stench.

“She’s right here.

We’re holding hands.”

The officers exchanged glances.

Peton put his shoulder to the door.

The old wood gave way on the second attempt, the lock tearing free with a crack.

What they found inside would haunt both men for the rest of their lives.

III.

A Hand That Would Not Let Go

The flat was a single, dark room.

In the center stood Emma Hartley, age seven, wearing a filthy dress that might once have been white.

Her blonde hair hung in matted tangles.

She was painfully thin, cheeks hollow, eyes enormous.

She was holding someone’s hand.

The hand belonged to a woman sitting in a wooden chair.

The woman wore a dark Victorian dress with a high collar.

Her head was tilted to the side.

Her eyes were open but clouded, staring at nothing.

Her skin had a gray-green tint and had begun to slip away from the tissue in sheets.

Flies crawled across her face.

Emma looked up at the constables and said, perfectly calmly, “Mama’s been very tired.

She needs to rest.

We’ve been waiting for her to wake up.”

Constable Morris stumbled backward and vomited.

Sergeant Peton, fighting his own nausea, knelt in front of Emma, careful not to startle her.

“Sweetheart,” he said gently, “how long has your mama been resting?”

Emma thought for a moment, face scrunching with concentration.

“Since my birthday.

I don’t know how many days.

I tried to count, but I lost track.

We had a cake.

Then Mama sat down and went to sleep and wouldn’t wake up anymore.

But she told me to never let go of her hand.

So I didn’t.

I’ve been very good.”

Three weeks.

The child had been alone with her mother’s corpse for three weeks, holding her hand the entire time, believing she was simply asleep.

IV.

The Photographer’s Visit: A Portrait of the Dead

Two days before police discovered Emma and her mother’s body, something very strange happened.

On August 13, 1899, a man knocked on the door of 47 Thrall Street.

His name was Thomas Whitmore, a traveling photographer specializing in post-mortem photography—the Victorian practice of photographing the dead as a final memorial.

Post-mortem photography was common in the 1890s.

Mortality rates were high, photographs were expensive, and for many families, the only image they’d ever have of a loved one was taken after death.

Photographers would pose bodies to look lifelike, sometimes propping them in chairs, opening their eyes, or positioning them with family.

Thomas had received a commission letter four days earlier, delivered by a street child.

Written in a feminine hand:

> Mr.

Whitmore, I require your services for a memorial photograph.

I am very ill and do not expect to recover.

I wish to have one final photograph with my daughter Emma before I pass.

Please come to 47 Thrall Street, Whitechapel on August 13 at 2:00 p.m.

Payment of two pounds will be left under the doormat.

Please knock twice and enter.

We will be waiting in the garden behind the building.

Miss A.

Hartley.

Thomas found the request unusual but not unprecedented.

Two pounds was generous.

He assumed Miss Hartley was bedridden and wished to pose for a last photograph before death made her appearance too unsettling.

He arrived at 2:00, found the two pounds under the mat, knocked twice.

No answer.

Following instructions, he tried the door—it was unlocked.

“Hello, Miss Hartley?” The smell hit him immediately.

Sweet, rotten.

But Thomas had worked with death for 15 years.

He assumed Miss Hartley had already passed, and perhaps a family member wanted the photograph taken quickly before burial.

He heard a small voice from outside.

“We’re in the garden.

Mama said you’d come.”

Thomas walked through the flat, breathing through his mouth, and stepped into the garden.

There, in a patch of sunlight, stood a little girl in a white dress holding the hand of a woman seated in a chair.

The woman was angled away from the camera, her face in shadow beneath a wide-brimmed hat.

Her free hand rested in her lap.

She was perfectly still.

The little girl smiled.

“Mama’s ready for her picture,” Emma said brightly.

“She said it’s very important.

You must take it exactly the way we’re standing, holding hands.

She said I must never let go.”

Thomas set up his camera.

The composition was lovely: afternoon light, overgrown roses, mother and daughter holding hands.

The woman’s stillness was perfect for the long exposure.

He never questioned why the woman didn’t move or speak.

He assumed she was already dead and had been carefully posed.

That’s what he did, after all.

That’s what he was paid for.

He took the photograph, packed his equipment, and left—never knowing the full horror he had just documented.

V.

The Scream That Broke the Spell

When Sergeant Peton gently pulled Emma away from her mother’s body on August 15, the child screamed—a sound Peton would hear in his nightmares for decades.

Not fear, but anguish and betrayal.

Emma fought with shocking strength, trying to reach back for her mother’s hand.

“No, no, Mama said never let go.

She made me promise.

I have to hold her hand or she won’t wake up.

Let me go, Mama!”

It took both constables to carry Emma out while she thrashed and sobbed.

Mrs.

Blackwood took the child upstairs, cleaned her, tried to feed her soup, but Emma wouldn’t eat.

She just stared at the floor and whispered, “I let go.

I wasn’t supposed to let go.”

Downstairs, the police began their investigation.

VI.

The Suicide and the Letter

Dr.

Harold Greaves, the police surgeon, arrived to examine the body.

Miss Adelaide Hartley, aged 31, had been dead for about three weeks—matching Emma’s account of “since my birthday” on July 25.

Cause of death: morphine poisoning.

An empty bottle labeled “laudanum” was found on the floor, along with a teacup containing dried residue.

Laudanum, an opium tincture, was common for pain relief, but in sufficient quantity, it caused respiratory failure.

But what they found next turned a sad death into something far more disturbing.

In the woman’s lap, beneath her hand, was a letter.

Sergeant Peton unfolded it:

> To whoever finds this, I am Adelaide Hartley.

I am dying of consumption, and the pain has become unbearable.

I have taken laudanum to end my suffering.

I know this is a sin, but I cannot bear it any longer.

My daughter Emma is seven and has no other family.

I have arranged for one final photograph of us together.

The photographer will come on August 13.

Emma believes I am only sleeping.

I have told her she must hold my hand and never let go until someone comes.

I know someone will come eventually.

Please tell Emma I am sorry.

Please tell her I loved her.

Please tell her it wasn’t her fault that I couldn’t wake up.

Take care of my girl.

She deserves better than what I could give her.

> July 25, 1899.

Peton’s hands were shaking.

Adelaide Hartley had committed suicide by laudanum, but planned it with chilling care.

She wrote to the photographer, arranged payment, positioned herself in the garden chair in the pose she wanted for the photograph, and told her daughter to hold her hand and never let go.

Emma had stayed in that room for three weeks, eating bread and cheese her mother had left out, drinking water, sleeping on the floor beside her mother’s chair, always holding that hand.

As the body decomposed, as the smell grew worse, Emma held on—because Mama had said never let go.

When the photographer came on August 13, Emma led him to the garden, still holding her mother’s hand, posed for the photograph as instructed, smiled because that’s what you do for photographs.

And Thomas Whitmore captured it all—a little girl holding hands with a corpse dead for 19 days, positioned in sunlight like a normal family portrait.

The child, unaware, smiling for a picture her mother had arranged from beyond death.

VII.

The Case That Shocked England

The “Adelaide Hartley Case” exploded in the London newspapers within 24 hours.

Headlines blared: “Child Holds Dead Mother’s Hand for Three Weeks—Whitechapel Horror Suicide,” “Mother Poses With Daughter for Post-Mortem Photo—The Girl Who Wouldn’t Let Go.”

The public was appalled and fascinated.

Some called Adelaide a monster for what she’d done.

Others saw her as a desperate woman trying to give her child one final gift.

The debate raged in newspapers, churches, and parliament—about suicide, parental duty, and Emma’s future.

But there was another element that disturbed investigators: How had Adelaide arranged everything so precisely? How had she timed the photographer’s visit for two weeks after her death?

Detective Inspector Arthur Wickham investigated.

Adelaide had been a seamstress, barely making enough to survive.

Diagnosed with advanced tuberculosis in early 1899, by July she was coughing blood and could barely work.

No family, no savings, no way to provide for Emma after her death.

Wickham discovered that Adelaide had spent her final weeks planning with chilling precision.

On July 10, she visited three chemists to buy laudanum, accumulating a lethal dose.

On July 15, she wrote to Thomas Whitmore, arranging the photograph and prepaying with borrowed money.

On July 20, she told Emma she would take a long sleep soon, but Emma must hold her hand until someone came to help.

She made it seem like a game, a test of love.

On July 25, Emma’s seventh birthday, Adelaide gave her a cake, then took the laudanum, positioned herself in the garden chair, and died holding Emma’s hand.

Adelaide had timed everything perfectly.

She knew the summer heat would accelerate decomposition, that neighbors would eventually notice the smell, that if Emma was found too quickly she’d be discovered with a fresh corpse, but if found after the photograph, there would be a memorial image.

Maybe that would comfort Emma someday, even if the circumstances were horrific.

Adelaide gambled that the photograph would happen before discovery.

She was right.

Whitmore took the photograph on August 13.

Police arrived August 15.

Her timing was perfect.

Wickham wrote in his notes: “Subject showed extraordinary premeditation in arranging her own death and subsequent discovery.

The psychological impact on the child is likely to be severe and permanent.

This is either the most loving or most monstrous act a mother could commit.

Perhaps it is both.”

VIII.

The Photograph: Evidence and Trauma

Thomas Whitmore came forward to police on August 17, after reading about the case.

He was horrified.

“I photographed a dead body,” he told Wickham.

“I posed a child with her mother’s corpse, and I didn’t even realize.

God help me.

I thought it was just another memorial photograph.

I thought the mother had just died—not that she’d been dead for weeks.”

Wickham asked to see the photograph.

Whitmore had already developed it, intending to send it to Thrall Street.

Now he handed it over, trembling.

The image showed exactly what witnesses described: a young girl in a white dress, standing in a garden, holding the hand of a woman seated in a chair.

The woman’s face was turned away, shadowed by a hat.

Roses climbed the brick wall.

Afternoon sunlight filtered through leaves.

It looked perfectly ordinary.

But Wickham examined it with a magnifying glass.

The woman’s hand, the one Emma held, showed discoloration—dark patches suggesting decomposition.

Her dress, where it touched her body, showed irregular bulges—her flesh bloating from internal gases.

Most disturbing: flies.

Tiny dark spots on her dress and in the air, rendered as blurs by the exposure time, feeding on decomposing flesh.

Emma’s face showed no awareness.

She was smiling slightly, looking toward the camera, her small hand clutched tightly in her mother’s.

Wickham ordered the photograph sealed in the case file.

Too disturbing for public viewing, but historically significant.

This was perhaps the only photograph ever taken of a living person posing with a corpse, unaware the person was dead.

One detail emerged later: when police examined Adelaide’s body, they found ligature marks on the wrist of the hand Emma had held.

Adelaide had tied her own hand to the chair before dying, ensuring it would remain in position for Emma to hold and for the photograph.

She had planned for her own decomposition, accounted for every variable, and succeeded.

The photograph was exactly as she envisioned—one final portrait of mother and daughter together, holding hands, in golden light.

IX.

Restoration Reveals the Unthinkable

For 120 years, the photograph remained sealed in Scotland Yard’s archives, referenced in criminal psychology texts and Victorian history, but rarely seen.

The few historians who requested access found it too disturbing to reproduce.

Then in 2019, Dr.

Sarah Chen, a digital restoration specialist at University College London, was granted access for a research project on Victorian photography.

She was interested in post-mortem photography and its cultural significance.

When she scanned Adelaide and Emma’s photograph at ultra-high resolution, 4,000% magnification, using forensic imaging, she discovered something invisible to Victorian observers.

In the shadowed area beneath Adelaide’s hat, barely visible even with magnification, was her face.

Digital enhancement revealed: Adelaide’s eyes were open, but collapsed inward, leaving dark hollows.

Her mouth had fallen open.

The skin had slipped from her cheekbones, giving her a skeletal appearance.

But there was something else—something that made Sarah Chen immediately contact Scotland Yard’s cold case division.

In Adelaide’s lap, partially hidden by her folded hand and the shadows of her dress, was another piece of paper—a second letter never found by the original investigators.

Scotland Yard reopened the case file and sent forensic specialists to University College London.

Using Sarah’s scans, they read the text on the paper in Adelaide’s lap—text invisible to the naked eye, but clear under digital enhancement.

It was dated August 12, 1899—one day before the photographer’s visit, and 18 days after Adelaide’s death.

> Emma, if you are reading this, it means you survived.

> It means you held on.

> It means you were found.

> I am so sorry, my darling girl.

> I know you don’t understand now.

> You think I’m sleeping.

> You think if you hold my hand tightly enough, I’ll wake up.

> But I won’t, sweetheart.

I’m gone.

> What I’ve done to you is unforgivable.

> But I had no choice.

I was dying anyway, and I could not bear the thought of you starving alone after I died naturally.

> This way you’ll be found quickly.

> This way there will be a photograph of us together.

> This way you’ll have something to remember me by.

> Hold my hand, Emma.

Never let go.

> Not because it will wake me, but because it means we’re together just a little bit longer.

> I love you.

I’m sorry.

Forgive me if you can.

> Mama

The date was impossible.

Adelaide had died on July 25.

This letter was dated August 12—18 days later.

Either Adelaide Hartley had somehow written a letter nearly three weeks after her death, or someone else had placed this letter in her lap between July 25 and August 13.

But who? Emma couldn’t write.

The flat had been locked from the inside.

No one else had entered until the photographer arrived.

Scotland Yard examined the photograph again.

The paper in Adelaide’s lap was present in the photograph taken August 13, 1899.

It wasn’t added later.

It wasn’t a hoax.

Which meant either Adelaide had written this letter after her own death, or someone—or something—had been in that locked flat with Emma during those three weeks.

The case file remains open.

The photograph is still in the archives, now flagged with a notation: “Unexplained elements.

Further investigation pending.”

X.

The Girl Who Wouldn’t Let Go

Emma Hartley was taken in by a distant cousin, raised in Manchester.

She married in 1912, had three children, and died in 1964 at age 72.

She never spoke publicly about what happened in that flat, but her daughter reported that Emma, even as an old woman, would sometimes reach out in her sleep and grasp at empty air, her fingers closing around something invisible—holding tight to a hand that was no longer there.

In 2023, a paranormal investigation team requested access to the photograph, claiming modern spectral analysis showed anomalous energy signatures around the seated figure—patterns that couldn’t be explained by photographic defects or decomposition gases.

Scotland Yard denied the request.

The photograph remains sealed.

Some mysteries, perhaps, are better left unsolved.

Some hands, once released, should never be grasped again.

And some photographs capture more than light and shadow.

They capture the terrible lengths to which love will go—even beyond death—to protect what it cherishes most.

XI.

The Legacy of a Photograph

The case of Adelaide and Emma Hartley remains one of the most disturbing, enigmatic, and heartbreaking stories in Victorian crime history.

It’s a story that asks impossible questions about love, trauma, and the boundaries between life and death.

In the end, a photograph meant to capture a family’s love became evidence of horror—a testament to the unimaginable suffering hidden behind closed doors, and the desperate lengths a mother will go to leave her child with a memory, even at the cost of innocence.

What else are we missing when we look at the faces in old photographs?

Subscribe for more disturbing mysteries hidden in historical photographs.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load