A Picture-Perfect Scene—Or So It Seemed

The photograph arrived in a battered donation box from Leadville, Colorado, tucked between mining maps and payroll ledgers.

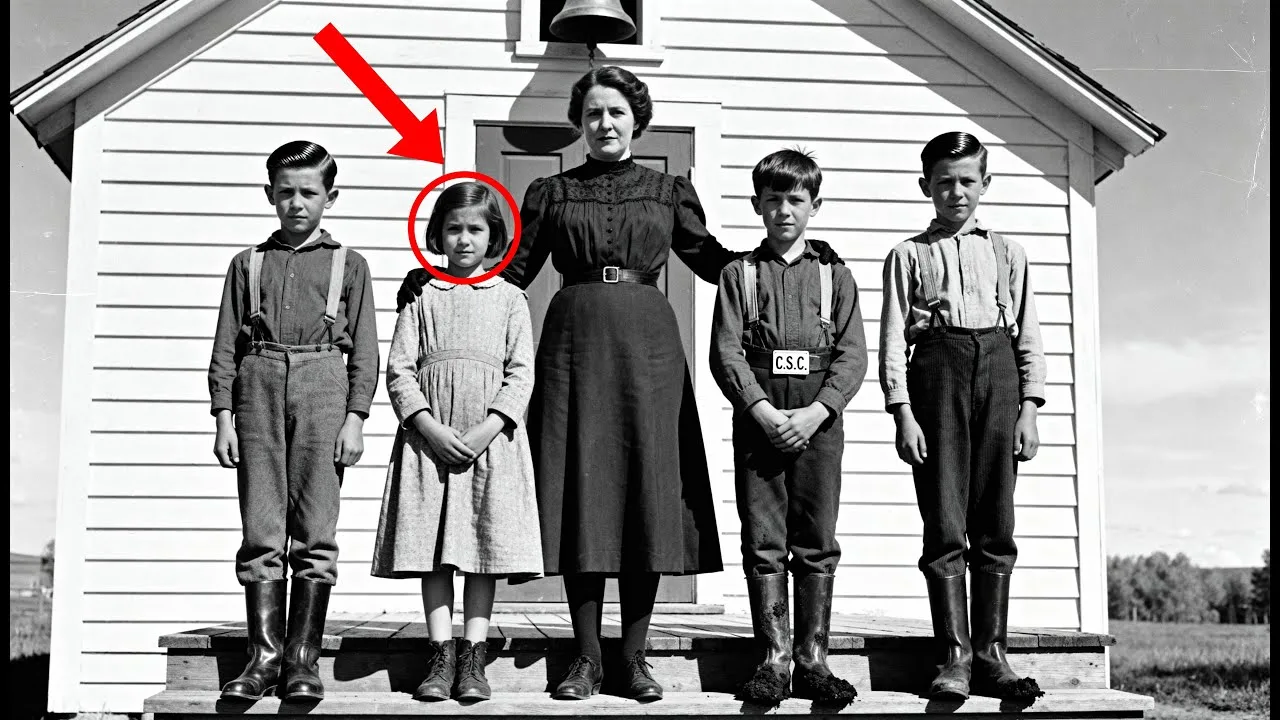

At first glance, it was the kind of image archivists like Sarah Chen saw every day: a proud teacher, five students, and a freshly whitewashed schoolhouse.

September sunlight gleamed on the bell above the door, and everything about the composition suggested progress—education as a civilizing force in a rough mining camp.

Sarah almost filed it away as “Education, Rural Schools, 1890s.” But something stopped her.

She pulled the print back under the magnifying lamp.

That’s when she saw it—the middle boy’s belt buckle.

Rectangular, stamped metal, and, even in sepia, the letters were clear: CSC.

Consolidated Silver Company.

The same initials on every document in the box.

It was a detail that made no sense.

Why would a schoolboy wear company property like a badge of ownership?

## Chapter 1: The Belt Buckle’s Secret

Sarah had spent twelve years cataloging mining town photographs.

She knew the visual language of exploitation—men with company numbers pinned to their chests, families in identical company houses, children thin from debt.

But schools were supposed to be different.

Schools meant hope, a way out.

She turned the print over.

“New school, September 1896.

Miss Harrow, teacher,” read the careful handwriting.

Below, in a hurried scrawl: “Submitted for board inspection.” Someone had taken this photo as proof.

Sarah scanned the print at high resolution and dug into the donation materials.

The Consolidated Silver Company had operated a major mine in Pitkin County from 1883 until a collapse in 1902.

The papers belonged to Martin Kellerman, superintendent from 1894 to 1899, and included everything from blasting schedules to grocery orders.

Somewhere in these documents, Sarah believed, was the answer to why a schoolboy wore a company buckle.

## Chapter 2: Mining the Archives

Colorado passed compulsory education laws in 1889, requiring children ages 8–14 to attend school for at least twelve weeks a year.

Mining companies resisted, but by 1896 most towns complied—at least on paper.

Company records confirmed that Consolidated Silver funded the Pitkin Flats schoolhouse in spring 1896.

Board minutes mentioned hiring Miss Harrow from Denver to instruct the children of employees.

Sarah found Alice Harrow’s name on a payroll ledger: $20 per month, room and board provided.

The 1900 census listed her as age 24, occupation teacher, living in a boarding house in town.

But by 1900, the school at Pitkin Flats had vanished from documentation.

A county newspaper from October 1897 offered a clue: “The educational experiment at Pitkin Flats has concluded.

Students have been absorbed into town facilities.” Sarah noted the strange phrasing.

Experiments end.

Experiments can fail.

## Chapter 3: Contracts and Control

Sarah contacted Dr.

Marcus Reeves, a historian specializing in labor practices during the silver boom.

She sent him a scan of the photograph and her notes about the buckle.

He called back within two hours.

Had she seen any contracts about apprenticeship or educational advancement?

Three days of sorting through Kellerman’s papers led Sarah to a folder labeled “Youth Initiative, 1895–1897.” Inside were dozens of printed forms: “Agreement for Educational Advancement.” The language was elaborate, but the meaning was clear.

Parents signed over a child, typically ages 10–14, to the company’s care.

In exchange for free education and meals, the child worked a half-shift in surface operations—four hours per day, six days per week.

The contracts promised “light duties only,” but listed jobs like hauling slag, sorting, assisting in the wash house.

Service lasted two years; at the end, the child received a certificate of education and a $40 wage bonus if behavior was satisfactory.

Most contracts were signed by fathers with immigrant names, mothers who marked X because they couldn’t write.

The company offered the program as charity—a way for poor families to educate children they couldn’t afford to keep out of the mines.

Dr.

Reeves was silent for a long time.

Then he said these contracts were illegal.

Colorado restricted child labor under age 14 in mines as of 1887.

Enforcement was weak, but the law was clear: children could not work underground, and surface work required proof of school attendance.

The company inverted the equation, using school as justification for labor.

The belt buckle was not decorative—it was identification.

Every child in the program wore one, marking them as company wards.

If a child tried to leave or a parent tried to withdraw them, the buckle proved ownership.

Not legal ownership, but the kind that mattered in a town where the company controlled housing, food, wages, and law enforcement.

## Chapter 4: Childhood for Sale

Sarah looked at the photograph again.

The boy with the buckle stood in the center.

His name, she now knew, was James Novak.

His father signed him over in June 1896.

James was eleven.

His contract listed duties: hauling slag, four hours per day.

Sarah found forty-seven names over two years—mostly boys, but eight girls.

Their duties included laundry, kitchen work, and packing blasting powder.

The youngest was nine.

Sarah needed to see the place.

She drove west from Denver to Pitkin Flats, now a ghost town.

The schoolhouse was gone, only the foundation remained.

The main mine entrance was sealed.

Fifty yards downhill, she found the waist dump—low ridges of slag softened by a century of rain.

Bits of metal surfaced in the dirt.

She found a rusted buckle, the initials gone, but the shape matched.

She sat on a rock, imagining eleven-year-old James Novak, hands raw from hauling slag, sitting in a classroom trying to focus on arithmetic.

The cruelty was in the combination—the company didn’t just steal childhood, it did so in the language of charity.

## Chapter 5: The System Unmasked

Back in Denver, Sarah contacted Dr.

Lena Sokalof, a sociologist specializing in company towns.

Dr.

Sokalof explained that in a company town, everything ran through one entity—housing, food, medical care, even currency.

Adding education completed the circle.

Parents depended on the company for survival; if the company offered schooling, parents had to accept the terms.

Refusal meant losing housing and work.

Similar programs existed across the West, but the Consolidated Silver program was unusual for its documentation.

They wrote it down.

They photographed it.

They submitted it for board inspection.

They believed they had nothing to hide.

Sarah found more photographs.

One from 1896 showed children near the crusher, pushing carts loaded with rock.

Another from 1897 showed the schoolhouse interior: benches, a slate board, and, in the corner, a row of hooks holding belts—all with rectangular buckles.

The children removed them during lessons, then put them back on for work.

She found a letter from Alice Harrow dated September 1897, requesting release from her contract.

She cited health reasons, but the tone suggested something more: “I can no longer reconcile my duties as educator with what I observe.” The company granted her release.

The school closed the following month.

The children were transferred to the town school, but their labor contracts continued.

## Chapter 6: The Children’s Lives

Sarah traced the children’s later lives.

James Novak appeared in the 1910 census, age 25, occupation miner, living in Leadville.

He married in 1912, had three children, and died in 1931 from silicosis—a miner’s disease caused by inhaling rock dust.

His lungs had been damaged over decades underground.

Dr.

Reeves explained the trajectory: a boy entered the program at eleven, worked surface operations, exposed to silica dust.

By thirteen, he was hired for underground work.

By thirty, his lungs were failing.

The educational program trained him for a lifetime inside the mines, binding him to the company through a system designed to look like opportunity.

Sarah compiled everything into a report—photographs, contracts, correspondence, census records, medical data.

She presented it to the archive director, Robert Taine.

He asked what she wanted to do.

She said it should be exhibited.

The public needed to see how company towns functioned, how exploitation hid behind charity.

## Chapter 7: Telling the Truth

The archive’s largest donor was a foundation established by descendants of Colorado mining families, including Martin Kellerman’s great-grandson.

Putting this material on public display would be complicated.

A conference room meeting followed.

Senior staff debated the risks.

One educator was shaken.

Another argued that child labor was common, and it was unfair to judge the company by modern values.

Sarah countered: the program was illegal even in 1896.

Colorado had child labor laws.

The company violated them and disguised the violation as education.

That was fraud.

The legal consultant said the archive had no obligation to suppress the material, but also no obligation to highlight it.

Robert asked what the foundation’s response might be.

No one knew.

The foundation provided 30% of the budget.

Sarah argued that the archive’s mission was to preserve and interpret history, not to protect donors from uncomfortable truths.

The children in that photograph had no power.

The archive had the power now to tell their story.

Joan Herrera, a senior staff member, agreed.

She said the archive could not function as a public institution while operating as a memory keeper for wealthy families.

If the foundation pulled funding, they would seek other donors.

Suppressing the truth was not an option.

Robert decided: the archive would move forward with an exhibition built around the photograph and contracts.

Descendants would be contacted.

Scholars would contribute essays.

The foundation would be informed before the exhibition opened.

## Chapter 8: The Exhibition and Its Ripple Effect

Sarah spent six months developing the exhibition.

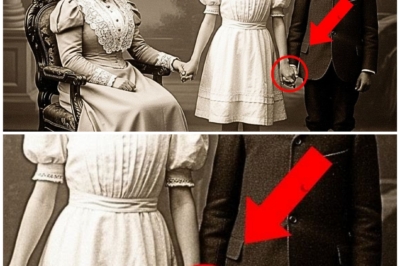

The centerpiece was the photograph of Miss Harrow and her students, enlarged with the belt buckle highlighted.

Beside it, an original contract—James Novak, with his father’s signature.

Sarah found census records for three more children.

One, Rose Kowalski, moved to California and lived to age 73.

Her granddaughter provided a statement: “My grandmother rarely spoke about her childhood in Colorado, but once mentioned working in a mine as a girl.

We assumed she meant cooking or laundry.

Now we understand she packed blasting powder.

She was ten years old.”

The exhibition opened in March.

Dr.

Reeves and Dr.

Sokalof gave talks on child labor and corporate control in the West.

Local media covered the story, focusing on the belt buckle as a symbol of ownership.

The foundation did not withdraw funding.

Instead, they issued a statement acknowledging the troubling practices and expressing commitment to historical transparency.

Whether it reflected genuine conviction or pragmatic PR, the material remained on view.

Other archives and museums responded.

Colleagues across the region sent similar photographs.

Teachers and students, company housing, families posed in front of schools.

Now they looked at those images differently, searching for overlooked details.

An archivist in Montana sent a 1902 photograph of children at a copper smelter, wearing cloth badges stamped with numbers.

Another in Wyoming found contracts nearly identical to the Consolidated Silver forms, used by a coal company in 1893.

The systems were not isolated incidents—they were shared strategies.

## Chapter 9: Unraveling the Lie

The exhibition traveled to other institutions.

More people came forward with family stories.

A man in his seventies told Sarah his grandfather worked in mines as a child, sent by parents who believed he was receiving an education.

A woman brought in a belt buckle inherited from her great-uncle, matching a lumber company in the San Juan Mountains.

The objects and stories accumulated, building a map of a system that had been everywhere in practice, nowhere in official history.

Photographs lie by omission.

They show what the photographer included, hiding everything outside the frame.

The 1896 image of Miss Harrow and her students was meant to demonstrate progress—a company investing in education, civilization arriving in a rough camp.

What it actually showed was control.

The school and teacher existed inside a system designed to extract labor from children, using their parents’ desperation as leverage.

The belt buckle was supposed to be invisible, just another piece of clothing.

But it became the thread that unraveled the entire lie.

## Looking Closer at History

How many other images hang in museums, printed in history books, framed in family homes—showing something their creators never intended to reveal? How many hands are positioned strangely because they are chained? How many children stand too still because they are terrified? How many objects in the background are tools of control, overlooked because we have been taught to see only the official story?

The work of re-examination is not about tearing down the past.

It is about reading it correctly.

Every photograph is evidence—not just of what was photographed, but of what the photographer assumed could remain unseen.

Sarah Chen’s discovery was not an anomaly.

It was an invitation to look closer at everything we think we already understand.

News

This photo of two friends seemed innocent until historians noticed a dark secret dec hashtags tag

The Photograph That Changed Everything Dr. Natalie Chen, senior curator of photography at the National Museum of American History, had…

This 1863 photo of two women looks elegant — until historians revealed their true roles

The Photograph That Refused to Stay Silent The Charleston Historical Society’s archives were quiet that Tuesday morning in March 2019….

This 1867 portrait of two sisters appears innocent—until historians uncovered its secret

A Photograph Hidden in Dust and Time The attic smelled of dust and forgotten time—a scent that clung to every…

1904 portrait resurfaces — and historians pale as they enlarge the image of the bride

A Wedding Portrait That Was Anything But Ordinary When the water-stained cardboard box arrived at the New Orleans Historical Collection,…

A Sweet Portrait of a Mother and Son — But the Reflection Behind Them Tells Another Story

The Picture That Hid a Family’s Secret On a crisp October afternoon, Margaret Foster stepped into the chilly, echoing halls…

It Looked Like an Innocent Portrait of a Mother With Her Kids — Until You Zoomed In on Their Hands

A Portrait’s Hidden Story It was supposed to be just another day in the archives. As the town historian for…

End of content

No more pages to load