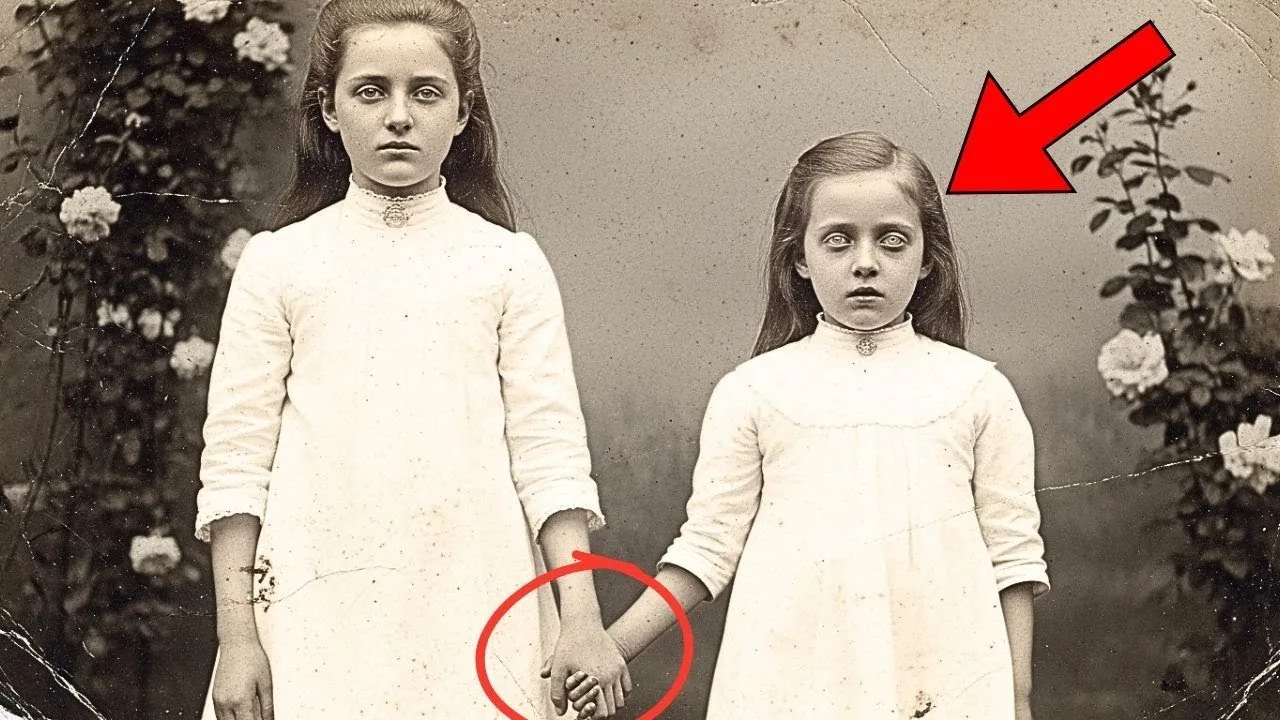

The first thing she saw was what anyone would see: two girls in white, holding hands beneath climbing roses.

The thing that stopped her wasn’t the dresses, or the trellis, or the prim seriousness that Victorian faces wore like duty.

It was a hand.

A child’s hand curled at an angle that anatomy doesn’t choose.

That was when Dr.

Helen Foster paused, ordered a high-resolution scan, and began peeling back 126 years of careful silence.

This is not a ghost story.

It’s a documentary one—a rare, disquieting collision of grief, technology, and the ethics of remembrance.

A single 5×7 photograph arrives anonymously at the Boston Historical Society in 2021; a curator notices a detail most would miss; a scanner draws out what love and shame tried to hide.

What it reveals recasts the entire image: not a portrait of two living sisters, but a promise engraved into paper by a dying child.

And once you grasp what that promise cost, you’ll never look at old family portraits quite the same way.

—

The Envelope That Wouldn’t Be Quiet

Plain manila, no return address—March 15, 2021.

Inside: a sepia-toned photograph mounted on thick card, the kind sold by Boston studios in the 1890s.

Two girls in white dresses stand in a garden, fingers locked.

A faded caption scratched along the mount in brown ink: “Lily and Rose Davies, June 1895.” A modern note on shaky paper rides along like a confession: “The Davy’s sisters, 1895.

May they finally rest.

I can’t keep this any longer.

Someone should know the truth.”

For most of the 18 years she had managed the Society’s photo archives, Dr.

Helen Foster measured each print by context: studio, chemistry, mount.

This one, on first glance, slotted easily into the familiar Boston-wealth tableau—lace collars, pulled-back hair, that posture the era taught children to hold.

But the hand pulled her back.

Rose’s right hand, the one Lily clasps: wrong texture, wrong angle.

In an age when curators triage more than they rescue, the decision to escalate to a multi-spectrum scan is a judgment call.

Helen made it.

What resolved on the screen was not merely detail.

It was an ethical question.

—

A Photograph Under a Microscope

High-resolution scanning (12,800 dpi) is as close as we get to time travel without delusion.

It takes chemistry, silver halide crystals, and patience, and asks them all to confess.

With an imaging specialist at her side, Helen watched as visible, infrared, and ultraviolet layers stitched themselves into a portrait the human eye cannot fully hold.

The mount paper composition tracked to late-19th-century stock; the emulsion came clean—no modern forgery here.

Then Marcus Chen, the imaging lead, pushed to 800% and then 1,600% magnification on Rose’s hand and face.

Suspicions hardened into anatomy.

Where Lily’s hand showed fine dermal lines and elasticity visible even through sepia, Rose’s displayed a waxy, inelastic sheen.

The fingers were rigid—not held by muscular tension, but positioned.

The skin tone was uneven in ways the Victorian tonal wash couldn’t erase.

IR layers separated “living” reflectance from uniform reflectivity.

Lily’s face and hands presented the microscopic scatter you see in living tissue captured on nineteenth-century emulsion (a vestige even a century later); Rose’s did not.

Her eyes were clouded.

The mouth slackened.

Powder dabbed to revive cheeks that refused blush.

A tongue desiccated at the edge.

And along the mount, faint graphite rose through contrast enhancement—childish scrawl that read like a testimony to no one and everyone: I promised Mama I would hold her hand forever.

I kept my promise.

June 12th, 1895.

Postmortem photography happened in the 19th century.

Families posed the dead openly and called it memorial.

This was not that.

This was a deception meant to offer comfort to two parents—and to a child who believed promises outrank biology.

Helen had a photograph.

She needed a family.

—

Finding the Davies

Genealogy is infrastructure for grief; archives give it weight.

The Davies family surfaces in census and city directories in Beacon Hill—Robert (textile merchant), Eleanor (old Boston name), daughters Lily (b.

March 1884) and Rose (b.

September 1888).

Death certificates, Massachusetts State Archives: Rose dies June 3, 1895—scarlet fever.

Lily dies June 10, 1895—same cause.

Burial registers at Mount Auburn: joint interment, June 11.

A note on Rose’s interment: “Delayed interment due to family circumstances.

Body held at family residence June 3 to 10.”

June in Boston was an 80-degree week, the paper said.

The weather records agree.

The Boston Globe’s June 12 brief wrote what respectable papers write: a prominent family mourning two children lost inside a week.

A line buried near the end gave this story breath: Lily refused to leave her sister’s side and insisted on remaining with her even after Rose’s passing.

The city health department kept a different kind of record.

Dr.

Samuel Morrison’s report—June 8, 1895—documents a physician called by neighbors to 44 Beacon Street for “welfare concerns.” He found Lily, feverish, sleeping beside her dead sister for five days, refusing separation.

The father was weak with scarlet fever himself.

The mother collapsed into grief.

The doctor recommended urgent intervention.

It did not come.

At some point between June 3 and June 10, a photographer was summoned.

—

The Man Behind the Lens

The Boston Photographers Guild ledger preserves more than commerce; it captures decisions people make when they want to freeze time.

Helen found an entry from Thomas Blackwell, memorial portrait specialist: June 7, 1895.

“Davies Residence, 44 Beacon Street.

Memorial portrait.

Two subjects.

Special arrangements.

Payment $50.”

In 1895, fifty dollars would buy a month’s wages.

It also buys silence.

When Helen asked for Blackwell’s diary—donated by a granddaughter in 1957—archives delivered brittle pages and the line where commerce meets conscience:

Received urgent summons to the Davies household… The younger daughter, Rose, died of scarlet fever 4 days ago.

The older daughter, Lily, will not survive long, says their physician.

Lily refuses to leave her deceased sister’s side.

She demanded I make a photograph that shows them both alive so “Mama can remember us together.” I tried to suggest a traditional memorial portrait.

She became hysterical.

I agreed.

God forgive me.

I posed them in the garden at Lily’s insistence, dressed in white, hand-in-hand, arranged to conceal death.

The older girl never stopped crying.

She whispered to her sister throughout.

I finished quickly.

The father paid double and begged me never to speak of it.

It is rare to possess the moral metadata of a photograph.

Here, it exists: a child’s agency, a parent’s acquiescence, a professional’s reluctant complicity.

The image, decoded by a scanner, found its own diary to testify.

It wasn’t meant to fool the public.

It was meant to prop up two parents at the edge of collapse and allow a child to fulfill a promise she believed sacred.

—

The Promise

“I promised Mama I would hold her hand forever.” In the context of a Victorian death culture, that sentence sounds earnest, tragic, and figurative.

In the context Helen reconstructed, it was literal.

Dr.

Morrison’s May 28 note—six days before Rose’s death—records Lily’s refusal to leave, an early fever in Lily, and a mother’s request: Hold your sister’s hand until everything is better.

Words intended as comfort hardened into contract.

Lily remained.

She held Rose’s hand through illness, then through death, then through a week of June heat.

She demanded a photograph that made the promise visible.

And then she died—scarlet fever complicated by exhaustion and grief, according to Morrison’s postmortem note.

“Patient refused all food and water in final 48 hours.

Last words: ‘I kept my promise.’”

Promises preserve and destroy.

The photograph’s inscription, faint graphite pulled from the mount’s fibers, is not just a caption.

It’s a verdict.

—

What Grief Does to the Living

The rest of the record reads like a ledger of human cost.

Eleanor Davies entered a Boston asylum in August 1895 with “acute melancholia and nervous prostration.” She spent 12 years mostly unresponsive, staring at the photograph.

A surviving letter drafted but never mailed—dated 1901—pierces the record’s formality:

My dear Lily, I should never have asked you to make that promise… You took my careless words and turned them into an obligation that cost you your life… You died because of a promise you should never have had to keep… The photograph torments me because it shows the exact moment of your sacrifice… I’m sorry, my darling girl.

Please forgive me.

Please rest.

Robert sold the Beacon Street house, moved, remarried, unremarried, and died at 49.

His obituary footnoted his first family.

The photograph traveled a different route: from Eleanor’s asylum room to her sister Margaret’s trunk, to Margaret’s daughter Catherine’s bedroom closet, and finally to Catherine’s son, James Hartwell.

He is the man who sent it anonymously in 2021 with the line “May they finally rest.” When Helen tracked him down by the trail family history leaves for persistent people, he said what generational guilt sometimes sounds like: “My mother said it was cursed, not by magic, but by love.”

He died two weeks later.

—

The Ethics of Display

Archives aren’t neutral.

To catalog, to exhibit, to restrict—each is a choice.

When Helen presented her findings to the Society’s board, the debate was not about technology or authenticity.

It was about the ethics of turning private grief into public lesson.

One camp saw a rare artifact of Victorian mourning culture; another saw a child’s exploitation and a mother’s anguish frozen in a spectacle frame.

Helen argued for a third way: preserve and document; restrict casual display; allow qualified, contextualized access for scholars of photographic history, medical history, and cultural grief; refuse clickbait.

The board agreed.

The photograph lives, sealed and stabilized, in a restricted archive with a companion dossier: the scan layers, lab notes, genealogical records, physician reports, newspaper clippings, Blackwell’s diary entries, and a quiet warning that context is the only solvent strong enough for this kind of sorrow.

—

What the Science Says—and Doesn’t

It’s tempting to let technology adjudicate morality.

It can’t.

What multi-spectrum scanning did here is clarify facts that 19th-century eyes could not (or chose not to) see:

– Emulsion and paper chemistry anchored the image in the 1890s.

– IR reflectance separated living from non-living tissue signatures.

– Micro-surface analysis delineated postmortem features (corneal clouding, skin desiccation).

– Enhanced contrast revealed graphite hidden in the mount’s fibers—Lily’s inscription.

Science supplied proof.

It did not supply permission.

That came from a dying father-in-law who didn’t want his children to carry a photograph that had already carried four lifetimes’ worth of pain—and from a curator willing to spend hours on a detail most would ignore.

—

A Victorian Practice Misunderstood—and Misused

Memorial or “mourning” photography in the Victorian era is often misunderstood as grotesque.

In reality, it was frequently tender: a baby dressed in white among flowers, a mother’s hand resting on a child’s folded fingers.

Families named death without flinching, and portraits helped them hold what was about to blur.

This photograph bends that practice toward illusion.

It isn’t a mother memorializing a child in plain view.

It’s a child manufacturing comfort for a parent by orchestrating a tableau in which the dead appear to live.

The difference is not pedantic—it’s ethical.

The image insists on presence while erasing truth.

It was made at a dying child’s insistence.

That complicates judgment but doesn’t dissolve it.

—

Why This Photograph Matters Now

“Viral” has turned grief into content and content into currency.

We share old images for novelty and comment on them for optics.

This photograph resists that economy.

It forces viewers to slow down and asks questions that outlive the 1890s:

– What promises do we ask children to keep, and which of those promises cost them in ways adults didn’t forecast?

– When does an image console, and when does it collude?

– What is the duty of care in remembrance? For archivists? For families? For the public?

– How do we honor an artifact that is at once historical and profoundly private?

This isn’t just a Victorian curiosity.

It’s a case study in the ethics of visual culture—how images are made, why they are kept, and when they should be shown.

—

A Timeline, Clear and Unembellished

– May 1895: Rose Davies falls ill with scarlet fever.

Lily promises their mother to hold Rose’s hand “until everything is better.”

– June 3: Rose dies.

Lily refuses separation; remains beside Rose’s body.

– June 7: Thomas Blackwell photographs the sisters in the Davies garden at Lily’s request, posing the dead to appear alive.

– June 8: Dr.

Morrison files a welfare report; interment remains delayed.

– June 10: Lily dies, scarlet fever compounded by exhaustion and grief.

– June 11: Joint burial at Mount Auburn; funeral at Trinity Church.

– 1895–1907: Eleanor institutionalized, keeps the photograph in her room; Robert relocates; the image passes to Eleanor’s sister.

– 1957: Blackwell’s diary enters the Society; the photograph remains in family custody, sealed in a trunk.

– 1998: Catherine dies; the photograph passes to her son James.

– March 15, 2021: The image arrives anonymously at the Boston Historical Society.

– March 18: High-resolution, multi-spectrum scanning reveals postmortem details and Lily’s inscription.

– April 2021: The Society restricts access, publishes an internal report, and preserves the complete dossier.

—

Searchable Facts Without Sensationalism

– Boston Historical Society photograph, 1895—Lily and Rose Davies

– Victorian postmortem photography (memorial portrait) with living sibling

– Multi-spectrum scan (visible, IR, UV) reveals postmortem features

– Hidden inscription in pencil uncovered via contrast enhancement

– Beacon Hill scarlet fever outbreak, June 1895

– Mount Auburn Cemetery records—joint burial

– Thomas Blackwell (memorial photographer) diary

– Dr.

Samuel Morrison—health department report, Boston, 1895

– Ethics of displaying private grief images; archival access policy

—

What the Curator Learned

Helen learned that the smallest detail can force a record to speak differently.

She learned that archives are not mausoleums—they are agreements with the living to steward the dead.

She learned that sometimes the right answer to a public’s curiosity is “not like this.” And she learned that an inscription pressed lightly into cardboard can carry a century across a desk and set it gently in your hand.

The photograph remains sealed.

Not to hide.

To honor.

For Those Who Work with Images

If you handle historical photographs, this case offers a practice template:

– Always log provenance and anomalies immediately; the smallest suspicion can determine conservation triage.

– When dealing with potential postmortem subjects, consider multi-spectrum imaging to avoid misclassification and to protect against accidental public exploitation.

– Build an ethics review into your processing workflow for images likely to re-traumatize families or communities.

– Pair artifacts with primary-source context: ledgers, diaries, medical records.

Images alone seduce; documents restrain.

– Design display policies that calibrate access to harm: allow scholars in; keep casual traffic out; write didactics that instruct rather than entertain.

The Photograph, Reframed

Two girls stand in a garden under climbing roses.

They wear white, because the living and the dead both used to.

The older sister is clenching her jaw against tears because she’s keeping a promise she cannot keep much longer.

The younger sister’s hand is waxy, her eyes clouded, her face powdered to impersonate a blush that can no longer be coaxed.

The photograph is not pretending there was never a death.

It is pretending there was one less.

You may be tempted to think the inscription is melodrama.

It isn’t.

It is a field note from a child at the edge of language.

I promised Mama I would hold her hand forever.

I kept my promise.

Forever is a word children learn from adults, and adults do not mean it literally.

Lily did.

A Note on Language and Names

You’ll see “Davies” and “Davy’s” in different parts of the record.

The mount bears “Davies,” and contemporaneous Boston records confirm that spelling; the donor’s modern note uses “Davy’s,” likely a phonetic error or family variant.

We preserve both in the dossier to reflect the record faithfully and trace research threads accurately.

Why It Stayed Hidden

James Hartwell said it plainly: It was cursed—not by magic, but by love.

Artifacts carry weight.

Families assign meaning.

A photograph like this can become an altar or a wound.

Eleanor stared at it for 12 years; Margaret hid it for 50; Catherine told her son not to show it; James mailed it to strangers because he didn’t want his children to inherit the dilemma.

This is how history returns to the public: through exhaustion and love.

Closing Without Closure

If you came here for the shock, the image supplies it when magnified: a child’s glassy eyes, powder pressed into cold skin, a hand that doesn’t bend.

If you came for meaning, you find it in the pencil faintly scrawled into a mount that was meant to carry names and dates, not confessions.

The promise kept was not mercy.

It was love without a guardrail.

Archives cannot forgive.

They can only remember.

The Boston Historical Society did not hide the photograph to spare itself.

It restricted it to spare the girls from becoming content and to spare viewers from mistaking a private sacrifice for a public curiosity.

The photograph rests now, cold and secure, nested in inert tissue under controlled humidity, its scan layers encrypted and referenced.

What it shows cannot be unseen.

What it means cannot be exhausted.

And if, the next time you see a stiff child in a Victorian portrait, you feel a tremor at the posture of a hand or the cloud of an eye, remember: not every promise belongs to a camera.

Some belong to a mother’s careless sentence and a daughter’s literal heart.

Some don’t belong to us at all.

It is not a ghost story.

It is a record of how love can cross a line and of how a single detail—one curled hand—can ask a historian to step gently across 126 years and say, simply, we see you now.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load