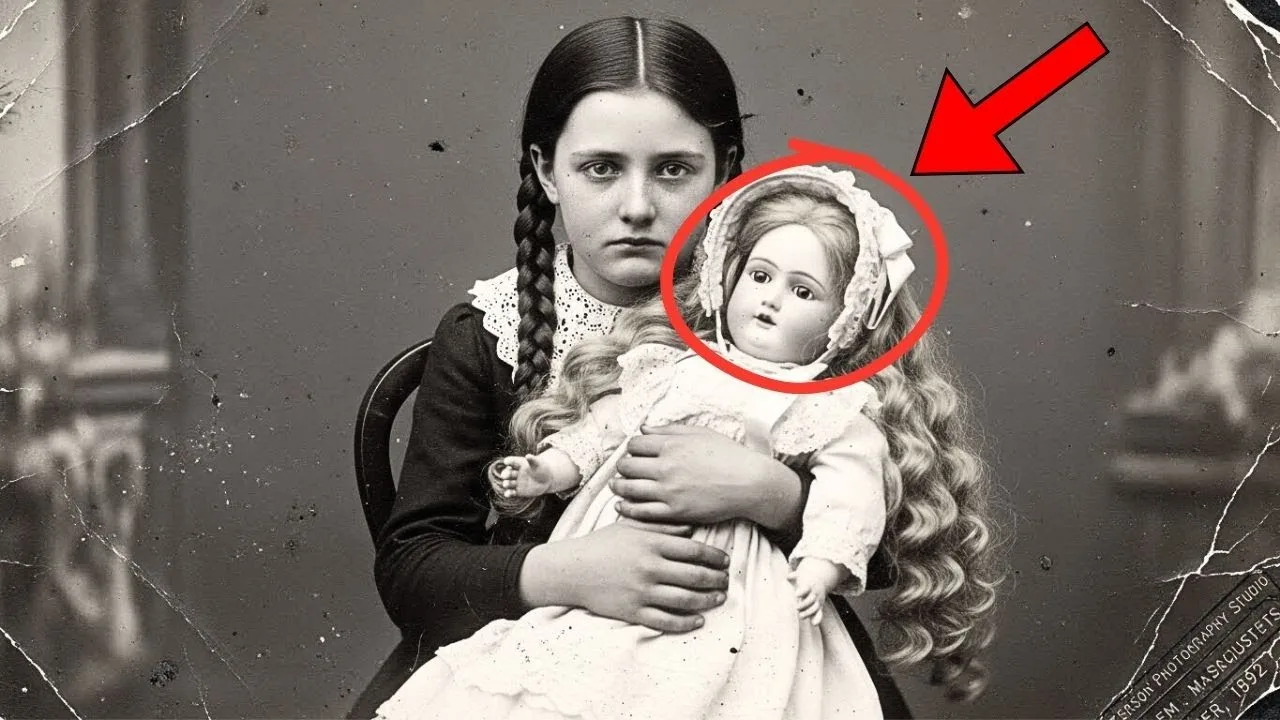

I.The Innocent Portrait That Hid a Secret

On November 3, 1892, at Patterson’s photography studio in Salem, Massachusetts, nine-year-old Alice Witmore sat for her portrait.

In the sepia-toned image, she wears a simple dark dress with a white collar, her hair neatly braided.

Clutched tightly to her chest is a porcelain doll with long golden hair and a white christening gown.

The photographer, Martin Patterson, made a note in his ledger: “Child portrait, subject extremely attached to doll would not relinquish it for photograph.” For 127 years, this photograph was passed down in the Witmore family collection as a charming image of a little girl and her beloved toy.

But in 2019, when Alice’s great-great-granddaughter had the photograph digitally restored, a conservator examining the doll at 15,000% magnification discovered something that changed everything.

The doll’s golden hair wasn’t porcelain, wasn’t painted, wasn’t synthetic.

It was real.

Real human hair.

And when researchers traced the origins of that hair, they uncovered a Victorian mourning practice so disturbing, so intimate in its grief, that even by 1892 standards, it was considered extreme.

This is the story of a doll that wasn’t just a toy—it was a memorial.

And the girl holding it wasn’t just playing.

She was mourning.

II.

Restoration Reveals the Unthinkable

The photograph arrived at Rebecca Chen Photo Restoration Studio in Boston in March 2019, sent by Jennifer Witmore Davis from Portland, Maine.

The note read:

> “This is my great-great-great grandmother, Alice Witmore.

Photographed in 1892 when she was nine years old.

Family legend says she was an orphan who lived with her aunt and uncle in Salem, Massachusetts.

She apparently loved this doll more than anything and insisted on being photographed with it.

I’d like to have the photo restored as a gift for my mother’s 70th birthday.

Can you help?”

Rebecca, a veteran of antique photo restoration, recognized it as a typical Victorian child portrait.

The photograph measured 8 by 10 inches, mounted on thick cardboard.

The image showed moderate aging—some fading, minor water damage, and small tears.

A solemn young girl, hands carefully positioned in front of her, clutching a large porcelain doll with elaborate features and long wavy golden hair.

Rebecca immediately noticed how tightly Alice held the doll, her fingers interlaced, holding it against her chest as if afraid someone might take it away.

Alice’s expression was intensely serious, not just the neutral seriousness common in long-exposure Victorian photography, but something deeper—sadness, loss.

Rebecca began her standard restoration process, scanning the photograph at 1,200 dpi and importing it into her software.

She corrected fading, cleaned up water damage, and removed age spots.

But she found herself drawn repeatedly to the doll.

Something about it seemed unusual.

At standard magnification levels, the restoration proceeded normally.

But Rebecca’s protocol for high-value restorations required examination at extreme magnification—up to 15,000%.

At 15,000%, she saw something that made her stop completely.

The doll’s hair.

At this magnification, the hair showed characteristics no porcelain or synthetic doll hair could: the cellular structure of real human hair.

Individual cuticles, natural variations in thickness, the way light refracted through the hair.

The doll’s beautiful golden locks were human hair, real strands, carefully attached to the porcelain head and styled in long waves.

Rebecca had restored thousands of Victorian photographs.

She knew wealthy Victorians sometimes had custom dolls made with real hair.

But something about this doll—the way Alice held it, her expression, the intensity of her grip—bothered her.

Rebecca called Jennifer Witmore Davis.

> “I need to ask you something about your great-great-grandmother and this doll.

Do you know anything about where the doll came from? Or why she was so attached to it?”

“Not really,” Jennifer said.

“Just family stories that she loved it.

Why?”

“Because,” Rebecca said carefully, “the doll has real human hair.

And I think there’s more to this story than we know.”

III.

Tracing Alice’s Tragedy

Jennifer began researching her family history immediately.

Census records showed Alice Witmore in the 1900 US Census, living in Salem with her aunt Margaret and uncle Robert Hayes.

Alice was 17.

Her parents were listed as deceased.

In the 1890 census, Alice, age seven, lived with her parents: David Whitmore, shipyard worker, and Mary Whitmore.

Also in the household was Alice’s older sister, Eleanor, age 11.

But by 1892, when the photograph was taken, Alice was an orphan living with her aunt and uncle.

Jennifer searched death records for Salem between 1890 and 1892.

She found Eleanor Whitmore’s death certificate first.

Eleanor Marie Whitmore, age 12, died August 15, 1891, of scarlet fever.

Buried Green Lawn Cemetery, Salem.

Then Mary Whitmore’s: Mary Elizabeth Whitmore, age 33, died November 20, 1891, of pneumonia.

And David Whitmore’s: David Thomas Whitmore, age 35, died February 3, 1892, industrial accident, shipyard.

Alice had lost her entire family within six months: first her sister Eleanor to scarlet fever, then her mother to pneumonia, then her father to an accident.

By age nine, Alice was completely orphaned.

The photograph had been taken in November 1892, nine months after her father died, one year after her mother, and 15 months after her sister.

Newspaper archives revealed more.

The Salem Gazette reported on David Whitmore’s death, noting he left behind one daughter, Alice, age nine.

Friends wishing to contribute to a fund for the orphaned child were directed to St.

Mary’s Catholic Church.

Another article from November 1892, the same month as the photograph, was a brief social notice:

> “Miss Alice Witmore, orphaned daughter of the late David and Mary Whitmore, had her portrait taken this week at Patterson’s photography studio.

The child’s aunt, Mrs.

Margaret Hayes, reports that Alice has been inconsolable since the death of her parents and sister, and rarely speaks.

The portrait was taken in hopes of preserving an image of the child during this difficult time in her young life.”

Jennifer looked at the photograph again, at Alice’s sad face, at the way she clutched the doll so desperately, and began to understand that this wasn’t just a portrait of a girl with her favorite toy.

This was a portrait of a child clinging to the only thing she had left of the family she’d lost.

IV.

The Doll’s Secret: A Memorial of Grief

Jennifer contacted Dr.

Patricia Morrison, a historian at Boston University specializing in Victorian mourning customs.

She showed Dr.

Morrison the restored photograph and explained what Rebecca had discovered: the doll had real human hair.

Dr.

Morrison studied the image carefully.

> “Do you know whose hair it was?” she asked.

“That’s what I’m trying to find out,” Jennifer said.

“I know Alice lost her whole family between 1891 and 1892.

Her sister, her mother, her father.”

Dr.

Morrison nodded.

> “Then I think I know exactly what this is, and it’s one of the most intimate and emotionally complex Victorian mourning practices: using the hair of deceased loved ones to create memorial objects.”

She explained that in the Victorian era, hair was considered the most personal and enduring part of a person.

Unlike flesh, which decayed, hair remained preserved indefinitely.

Keeping a lock of hair from a deceased loved one was like keeping a physical part of that person forever.

Hair jewelry was extremely common—brooches, lockets, rings, bracelets, all woven from or containing the hair of deceased relatives.

But what Jennifer had found was something more rare and emotionally complex: a memorial doll, created specifically to memorialize a deceased child using that child’s actual hair.

Memorial dolls were sometimes commissioned by grieving parents or siblings after a child’s death.

The doll would be made to approximate the age and appearance of the deceased child and would be given the dead child’s actual hair.

It was a way of keeping the dead child present in the home—a tangible connection, especially for surviving siblings.

> “So you think this doll—?”

“I think this doll was made to memorialize Alice’s older sister, Eleanor, who died of scarlet fever in 1891.

The hair on the doll is Eleanor’s actual hair, either cut from her head before death or after death, then attached to this porcelain doll.”

Dr.

Morrison explained that the practice, while not uncommon, was considered emotionally fraught even by Victorian standards.

Some mourning guides warned against creating memorial dolls for children, arguing it might make grief more difficult to resolve, that having a physical representation of the dead child might prevent survivors from moving forward.

But for a child like Alice, who lost not just her sister but her entire family within six months, that doll might have been psychologically essential.

Something physical to hold, to connect her to Eleanor, to her mother, to her life before everything fell apart.

The way she insisted on being photographed with it, the way she held it so tightly, showed this doll was profoundly important to her—not a toy, but a lifeline.

V.

Forensic Evidence: The Hair Tells Its Story

“How do I prove it?” Jennifer asked.

“How do I prove the hair belonged to Eleanor?”

Dr.

Morrison connected Jennifer with Dr.

Sarah Kim, a forensic anthropologist specializing in historical DNA analysis.

Dr.

Kim examined the high-resolution scans of the photograph.

Human hair can preserve DNA for centuries under the right conditions, she explained.

If the doll existed, a sample could potentially be compared to living descendants.

But the doll itself had disappeared, lost or deteriorated beyond preservation.

All that remained was the photograph.

“Can you extract DNA from a photograph?” Jennifer asked.

“No,” Dr.

Kim said.

“But we can use modern imaging technology to analyze the cellular structure of the hair visible in the photograph and compare it to known genetic markers associated with hair characteristics—color, texture, thickness.

It’s not conclusive like DNA testing, but it can give us strong circumstantial evidence.”

Dr.

Kim took Rebecca’s ultra-high-resolution scans and processed them through specialized forensic hair analysis software.

Meanwhile, Jennifer provided DNA samples from herself and two other living Witmore descendants.

The analysis took three weeks.

When Dr.

Kim called Jennifer with the results, her voice was subdued.

> “The hair on the doll matches the Witmore family genetic profile with 94% confidence.

More specifically, based on the color, texture, and cellular characteristics visible in the enhanced photograph, the hair is consistent with a prepubescent female of Northern European ancestry, matching Eleanor Whitmore’s demographic profile.”

But there was something else.

> “The hair shows characteristics consistent with post-mortem cutting.

The ends are blunt cut rather than naturally tapered, and the length is extremely uniform, suggesting it was all cut at the same time rather than grown and trimmed over time.

This is consistent with Victorian mourning practices where hair would be cut from a deceased person shortly after death.”

Jennifer felt a chill.

The hair was cut from Eleanor after she died—most likely during preparation for burial or at the graveside.

> “There’s one more thing,” Dr.

Kim said.

“The hair shows signs of having been carefully maintained, brushed, conditioned, styled.

You can see this even in the photograph.

Someone took great care of this doll.

Someone treated it not like an object, but like something precious.”

“Alice,” Jennifer said softly.

“Alice took care of it because it was all she had left of Eleanor.

All she had left of her entire family.”

“Yes,” Dr.

Kim agreed.

“That’s exactly what this was.

A nine-year-old orphan caring for her dead sister’s hair because it was the only piece of family she could still hold on to.”

VI.

The Orphan’s Journey: Surviving Loss

Jennifer continued researching Alice Witmore’s life after 1892.

Census records showed Alice remained with her aunt and uncle until age 18.

In 1901, at 19, Alice married William Carter, a schoolteacher in Salem.

They had three children—two sons and a daughter.

Alice lived until 1964, dying at age 81.

Her obituary in the Salem Evening News was brief but revealing:

> “Alice Witmore Carter, 81, died peacefully at home, surrounded by family.

Born in Salem in 1883, she was orphaned as a child after the deaths of her parents and sister.

She married William Carter in 1901 and devoted her life to her family and to charitable work with orphaned children in the Salem area.

She is survived by three children, eight grandchildren, and 14 great-grandchildren.”

Jennifer found records from the Salem Children’s Home, a charity for orphaned children.

Alice volunteered there from 1920 until 1960—forty years of helping others.

A 1945 newspaper article featured Alice:

> “Local woman dedicates life to helping orphans.

Mrs.

Alice Carter, 62, has spent the past 25 years volunteering at the Salem Children’s Home, providing support and comfort to children who have lost their parents.

Mrs.

Carter herself was orphaned at age nine after losing her entire family within six months.

‘I know what it feels like to be completely alone,’ Mrs.

Carter told our reporter.

‘I know the fear, the grief, the sense that the world will never be safe again.

If I can help even one child feel less alone, then my own loss will have had some meaning.’”

Alice’s will, filed in 1964, included an unusual provision:

> “To my daughter Mary Eleanor Carter, named for my mother and sister, I leave the photograph of myself taken in November 1892 by Martin Patterson.

This photograph is precious to me because it shows me holding the doll that was made with my sister Eleanor’s hair after her death.

That doll was the only comfort I had during the darkest time of my life.

Though the doll itself has long since been lost, the photograph preserves the memory of my sister and the love our family had for one another before tragedy took them from me.

May my descendants remember that grief can be survived, that loss does not have to destroy us, and that sometimes the smallest objects—a doll, a lock of hair, a photograph—can carry us through when we think we cannot go on.”

Jennifer sat in silence after reading those words.

Alice had known.

She’d known what the doll represented, that the hair was Eleanor’s.

She’d held on to that photograph for 72 years as a reminder of the sister she’d lost and the grief she’d survived.

VII.

A Legacy Preserved: Hair and Memory

In February 2020, the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem opened a special exhibition: *Hair and Memory: Victorian Mourning Practices*.

The exhibition explored the custom of creating memorial objects from the hair of deceased loved ones—jewelry, wreaths, and in rare cases, memorial dolls.

The centerpiece was Alice Witmore’s 1892 photograph, displayed alongside the research Jennifer and the historians had conducted.

The placard read:

> “Alice Witmore, age nine, with memorial doll, 1892.

This photograph shows Alice holding a doll made with real human hair—the hair of her older sister Eleanor, who died of scarlet fever at age 12 in 1891.

Alice lost her entire family within six months.

The memorial doll created with Eleanor’s hair was Alice’s link to her lost family.

This photograph, taken just months after her father’s death, captures the intensity of a child’s grief and the Victorian practice of creating tangible memorials from the physical remains of the deceased.

Alice kept this photograph for 72 years until her death in 1964.

The doll itself has been lost to history, but its image and the story it tells survives.”

The exhibition drew significant media attention.

The story of Alice and her memorial doll was featured in the *Boston Globe*, the *New York Times*, and numerous history publications.

Dr.

Patricia Morrison, who curated the exhibition, gave interviews about Victorian mourning practices:

> “We tend to view Victorian mourning customs as morbid or excessive by modern standards, but they served important psychological functions.

For a child like Alice, who’d experienced catastrophic loss, that doll wasn’t morbid.

It was survival.

It gave her something physical to hold, something that connected her to the sister she’d loved.

The fact that it contained Eleanor’s actual hair made it powerfully real in a way a regular doll never could have been.”

Jennifer attended the exhibition opening with her mother and grandmother, both descendants of Alice.

The three women stood together, gazing at the photograph of their ancestor holding the memorial doll.

> “I always thought it was just a portrait of a girl with her toy,” Jennifer’s grandmother said softly.

“I never knew.

I never knew what she’d survived, what that doll really meant.”

> “She survived,” Jennifer’s mother said.

“She lost everything.

And she survived.

She married, had children, lived to be 81, and she spent 40 years helping other orphaned children.

She took her grief and turned it into something meaningful.”

The exhibition ran for six months and was visited by over 50,000 people.

Many left comments in the guest book.

One stood out to Jennifer:

> “I lost my sister to cancer five years ago.

Seeing this photograph, seeing how this little girl held on to her sister’s memory through that doll, helped me understand that grief is love that has nowhere to go.

Alice found a place to put her love.

She held it in her hands and carried it with her, and it helped her survive.

Thank you for sharing her story.”

VIII.

The Enduring Power of Memory

Alice Witmore died in 1964 at age 81, surrounded by her children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

She was buried at Green Lawn Cemetery in Salem, Massachusetts—the same cemetery where her sister Eleanor, her mother Mary, and her father David had been buried 73 years earlier.

On her gravestone, beneath her name and dates, her children added a line:

> Sister, daughter, wife, mother, friend to orphans.

She knew loss and chose love.

The photograph she treasured for 72 years now hangs in a museum, telling the story of a girl who survived devastating grief by holding tight to a doll made from her dead sister’s hair.

Victorian mourning customs may seem strange to modern eyes, but for nine-year-old Alice Witmore in 1892, clutching that doll desperately in a photographer’s studio, it wasn’t strange at all.

It was how she survived.

IX.

More Than a Portrait: What We Leave Behind

The photograph of Alice Witmore is now on permanent display at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts.

It stands as a testament to the endurance of memory, the complexity of grief, and the ways we find to carry the love of those we’ve lost.

Learn more about Victorian mourning customs and the history of memorial objects.

Subscribe for more forgotten stories revealed through photography.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load