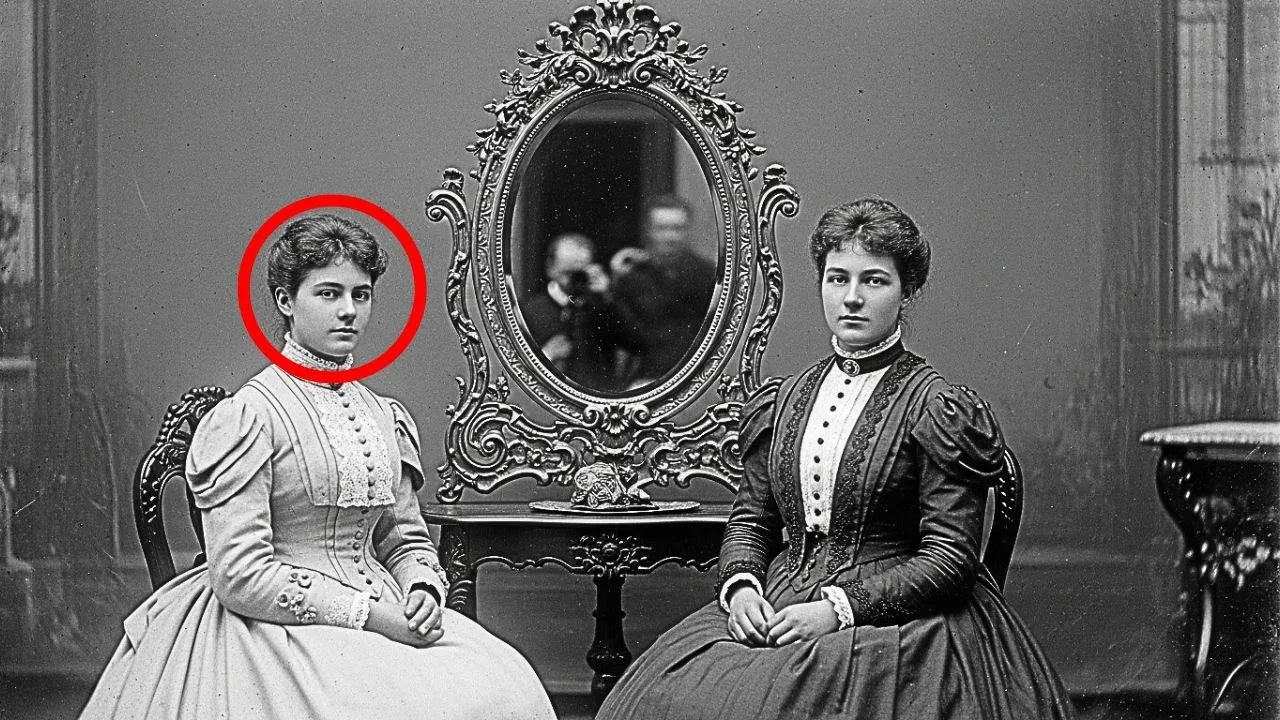

This 1889 sister portrait seems ordinary until historians noticed a dark secret.

The auction house on Newbury Street smelled of old wood and forgotten lives.

Emma Hartford moved through the dim room with practiced eyes, her fingers trailing over Victorian furniture and tarnished silver.

As a historical artifacts appraiser, she had learned to see beyond the dust and decay to the stories beneath.

But nothing had prepared her for what she would find that cold February morning in 2024.

The portrait sat propped against a mahogany dresser, almost overlooked among the estate sale clutter.

Two young women stared out from the sepia toned photograph, their faces composed in that rigid Victorian manner, unsmiling and formal.

The photographers’s stamp in the corner read, “Crawford Studios, Boston, March 1889.” Emma almost walked past it.

Almost.

Something made her stop.

Perhaps it was the way the older sister’s hands were clenched in her lap, knuckles white even in the faded image.

Or maybe it was the younger one’s eyes, wide, dilated, as if she’d seen something terrible just before the shutter clicked.

Emma lifted the frame carefully, wiping away 135 years of grime with her sleeve.

That’s when she saw it.

Behind the two women hung an ornate oval mirror, its gilded frame barely visible in the photograph’s background.

Emma squinted, then pulled out her phone, using the camera to zoom in on the reflection, her breath caught in her throat.

In the mirror’s surface, partially obscured but undeniably present, stood a third figure, a man’s silhouette positioned behind where the photographer would have been standing.

And in his hand, raised at an odd angle, was something that caught the light, something thin and pointed.

Emma’s pulse quickened.

She pulled the portrait closer, studying the sister’s faces again with new understanding.

That wasn’t formality in their expressions.

It was fear.

Emma purchased the portrait for $200, far more than the disinterested estate seller expected.

Back in her Cambridge apartment, she set up her examination station.

Highresolution scanner, magnifying lamps, reference books stacked within reach.

The sister’s faces seemed to watch her as she worked, their eyes following her movements around the room.

The highresolution scan revealed details invisible to the naked eye.

The figure in the mirror became clearer, a man in a dark coat.

His face turned slightly away from the camera, but his posture tense, predatory.

The object in his hand was definitely metallic with a distinctive curved handle.

Emma’s stomach tightened.

It looked like a surgical instrument or a weapon.

She turned her attention to the photographers’s mark.

Crawford Studios had been a prestigious establishment in Boston’s Backbay neighborhood, catering to wealthy families who could afford formal portraits.

Emma pulled up historical directories on her laptop, cross-referencing addresses and dates.

The studio had operated from 1885 to 1891, then abruptly closed.

No explanation in the records, just a final entry in the city directory and then nothing.

The sisters themselves were harder to identify.

Their clothing suggested upper middle class status, expensive fabric, well-tailored dresses, and the fashionable bustle style of the late 1880s.

The older woman wore a cameo brooch at her throat.

The younger had a delicate chain bracelet visible on her left wrist.

Emma photographed every detail, then began searching historical newspaper archives.

She started with March 1889, looking for society announcements, engagement notices, anything that might identify two sisters photographed together.

Hours passed, her coffee grew cold.

Outside, afternoon faded into evening, and still she searched.

Then, just before midnight, she found it.

A small obituary dated April 15th, 1889, exactly 3 weeks after the photograph’s stamp date.

Elizabeth Caroline, aged 24, beloved daughter of the late merchant Jonathan, died at home following a tragic accident, survived by her sister Sarah.

The Boston Public Libraryies archive room was silent except for the whisper of old paper and Emma’s careful breathing.

She’d requested every newspaper from April 1889, and now they lay spread before her like pieces of a puzzle that refused to form a complete picture.

The obituary for Elizabeth was brief and deliberately vague.

Tragic accident at home.

No details, no explanation.

Emma had seen enough Victorian death notices to know this was unusual.

When young women from prominent families died, the papers typically included more information.

Illness, carriage accidents, complications from childbirth.

The studied vagueness suggested something the family wanted hidden.

She found a longer article 3 days after the obituary buried on page seven of the Boston Daily Globe.

Mystery surrounds death of society woman.

The reporter had managed to extract a few more details from anonymous sources.

Elizabeth had been found at the bottom of the stairs in her family’s Beacon Hill townhouse.

Her neck was broken.

The family physician, Dr.

Marcus Webb, had signed the death certificate, ruling it an accidental fall, but neighbors reported hearing raised voices that evening.

and Elizabeth’s sister Sarah had been in the house at the time, though she claimed to have been in her room, unaware of anything a miss until the housekeeper screams brought her running.

Emma photographed every article, then moved to city directories and property records.

The family had lived at 42 Mount Vernon Street, one of the most prestigious addresses in Boston.

The house had been sold in 1890, a year after Elizabeth’s death.

Sarah had moved to a modest apartment in the South End.

The dramatic change in circumstances was telling.

She pulled out the photograph again, studying Sarah’s face with new intensity.

The younger sister, the survivor.

Those wide, frightened eyes now seemed to hold secrets rather than innocence.

Emma needed to know more about what happened in that house on Mount Vernon Street.

Emma stood outside the brownstone at 42 Mount Vernon Street.

Comparing the current structure with a photograph from 1889 she’d found in the Historical Society archives.

The building remained largely unchanged.

Same steep front steps, same iron railings, same narrow windows looking out onto the brick sidewalk.

Somewhere behind those walls, Elizabeth had died.

But first, Emma needed to understand the photograph itself.

She returned to her research, focusing on Crawford Studios and its mysterious closure in 1891.

At the Massachusetts Historical Society, she found a reference to James Crawford in a photography guild newsletter.

Our colleagues sudden departure from Boston remains unexplained.

It read, “His studio closed without notice in June 1891, and he has not responded to correspondence.” What? The word departure felt deliberately euphemistic.

Emma requested police records from 1891.

What she found sent chills down her spine.

James Crawford had been reported missing on June 3rd, 1891, exactly 2 years and 3 months after he’d photographed Elizabeth and Sarah.

The police report was frustratingly brief.

Crawford had failed to open his studio one Monday morning.

His assistant, upon entering with a spare key, found the dark room in disarray.

Chemicals spilled, glass plates shattered on the floor.

Crawford’s coat and hat were still hanging on their hook.

His wallet was in his desk drawer, money untouched.

He had simply vanished.

The investigation had gone nowhere.

No body was ever found.

No witnesses came forward.

The case was filed away as an unexplained disappearance, one of many in a growing industrial city where people sometimes chose to start over elsewhere.

But Emma knew better now.

She pulled out the photograph, looking at the figure in the mirror’s reflection.

Had Crawford seen something while developing this image? Had he noticed, as Emma had, that there was someone else in the room who shouldn’t have been there? She needed to find out who that figure was? The pattern emerged slowly, but once Emma saw it, she couldn’t unsee it.

She had expanded her search beyond Elizabeth, looking at other deaths and disappearances connected to the house at 42 Mount Vernon Street.

What she found was disturbing.

Between 1886 and 1889, five young women had disappeared from the neighborhood.

All were domestic servants.

All had worked at one time or another for families on Mount Vernon Street or the surrounding blocks.

The police reports were dismissive.

Servants were transient, the officers noted.

They moved from position to position, sometimes left the city entirely without notice.

Their families, often poor immigrants, lacked the resources or social standing to demand thorough investigations.

But Emma noticed something the police had missed.

Three of the five women had worked directly in the house at number 42.

They’d been employed by Elizabeth and Sarah’s family before Elizabeth’s father died in 1887.

She found one name that appeared in multiple records.

Detective Patrick O’Brien, who had investigated two of the disappearances.

Unlike his colleagues, O’Brien seemed to have taken the cases seriously.

His reports were detailed, thorough.

He’d interviewed neighbors, checked employment records, traced the women’s movements and their final known days.

Emma tracked down O’Brien’s descendants through genealogy records.

His great-grandson, Michael O’Brien, was a retired police officer living in Dorchester.

When Emma called, explaining her research, there was a long pause on the line.

My great-grandfather kept personal files, Michael said finally.

Cases that bothered him, ones he felt never got proper resolution.

I have some of his papers in my attic.

You should come look at them.

Two days later, Emma sat in Michael’s living room, her hands trembling as she opened a leather portfolio marked Mount Vernon Street case, private.

Inside were newspaper clippings, handwritten notes, and photographs, and a list of names, eight women, not five.

Detective Patrick O’Brien’s handwriting was neat and methodical, each entry dated and cross-referenced.

Emma could almost hear his voice in the carefully documented observations.

Nobody cares when poor girls disappear, but somebody should.

The portfolio contained far more than official police reports.

O’Brien had conducted his own investigation, apparently on his own time.

He’d interviewed the families of the missing women, documented their testimonies in detail.

Each woman had last been seen in the vicinity of Beacon Hill.

Each had mentioned being offered better employment, higher wages.

Several had told family members they were meeting someone about a special position in a wealthy household.

None were ever seen again.

O’Brien had developed a theory, one he’d clearly never put in official reports.

Emma found it on a separate sheet dated November 1889, 7 months after Elizabeth’s death.

The disappearances stopped after the incident at 42 Mount Vernon Street.

He’d written Elizabeth died in April.

The last missing woman, Mary Sullivan, was last seen in March.

Coincidence? He’d drawn connections between the missing women and the household.

Three had worked there as maids.

Two others had interviewed for positions, but were told the family wasn’t hiring after all.

Another had worked for a neighbor and had been seen talking with someone from number 42 on the street.

O’Brien had attempted to interview Sarah after Elizabeth’s death, but she’d refused to speak with him.

Her lawyer had sent a formal letter telling the detective to cease harassing the grieving young woman.

After that, the investigation had stalled, but O’Brien had kept watching.

Emma found surveillance notes spanning months.

He documented who visited the house, when lights were on, when Sarah left and returned.

And then, in June 1889, 2 months after Elizabeth’s death, Sarah had moved out suddenly.

On the final page was a name Emma hadn’t expected.

James Crawford, photographer, approached him regarding observations at 42 Mount Vernon Street.

He seemed nervous, claimed to know nothing.

We’ll follow up.

The next entry was dated June 5th, 1891.

Crawford missing.

Coincidence? Sarah had vanished into obscurity after leaving Mount Vernon Street, but Emma was determined to find her trail.

The 1890 city directory listed a Sarah living at a boarding house on Columbus Avenue in the South End, a dramatic decline from Beacon Hills Prestige.

Emma visited the location, now a renovated apartment building, and then turned to census records and historical society archives.

The 1890 census confirmed it.

Sarah, age 22, occupation listed as seamstress, living alone.

Emma felt the weight of that decline.

From a wealthy household with servants to working with her hands for survival.

What had caused such a dramatic fall? The answer came from an unexpected source.

At the Boston Aanium, Emma found a collection of personal letters donated by a prominent family.

Buried in the correspondence was a letter dated May 1889, one month after Elizabeth’s death.

It was from a Mrs.

Elellanena Richmond to her sister in New York.

The scandal on Mount Vernon Street has the neighborhood in an uproar.

The letter began.

Poor Elizabeth is dead, and now terrible whispers surround the family.

Sarah has been quite shunned by society.

I heard she tried to attend the Winthrop reception last week and was turned away at the door.

Some say she knows more about her sister’s death than she told the police.

Others speak of darker things, missing servants, strange occurrences in that house when their father was alive.

The family’s reputation is in ruins.

Emma’s hands trembled as she photographed the letter.

Sarah hadn’t just moved out.

She’d been expelled from her social circle, her name tainted by association with whatever had happened at 42 Mount Vernon Street.

But there was more.

Emma found a marriage record from 1893.

Sarah had married a factory worker named Thomas Bennett.

They’d had two children.

Emma traced the lineage forward through births, deaths, marriages right up to the present day.

Sarah’s great great granddaughter was alive, living in Salem.

Her name was Katherine Howard, and she was 67 years old.

Emma made the call.

Catherine Howard’s house in Salem was filled with antiques and family photographs spanning generations.

She welcomed Emma with cautious curiosity, setting tea on the coffee table between them.

“You said on the phone, this was about my great great grandmother, Sarah,” Catherine began.

“I don’t know much about her.” The family never talked about that part of our history.

Emma placed the 1889 photograph on the table.

Catherine leaned forward, studying the two women’s faces, and something in her expression shifted.

Recognition perhaps, or pain.

I’ve never seen this before, she said quietly.

But I know who they are.

Sarah and Elizabeth, the sisters.

What did your family tell you about them? Emma asked.

Catherine was silent for a long moment, her fingers tracing the edge of the photograph.

When I was young, maybe 10 or 11, I found my grandmother crying in the attic.

She was holding a letter, very old, yellowed paper.

When I asked what was wrong, she said she’d learned something terrible about her grandmother, Sarah, something that had been hidden for decades.

Emma leaned forward.

What was it? My grandmother wouldn’t tell me the details.

said I was too young, but she told me that Sarah had kept a journal, and when she died in 1934, she’d left instructions that it should be burned.

My great-grandmother couldn’t do it.

She hid it instead, and it passed down through the family.

Each generation was told the same thing.

“Don’t read it.

Don’t speak of it.

Keep the secret buried.” “Do you have it?” Emma’s voice was barely a whisper.

Catherine stood and walked to an old secretary desk in the corner.

From a locked drawer, she removed a small leatherbound book, its pages yellow and brittle with age.

I read it once 5 years ago after my mother died.

I couldn’t sleep for weeks afterward.

She handed it to Emma.

Maybe it’s time someone did something with the truth.

Emma opened the journal with trembling hands.

The first entry was dated June 1889, 2 months after Elizabeth’s death.

Sarah’s handwriting was shaky, the ink blotted with what might have been tears.

Emma read aloud, her voice barely steady.

June 15th, 1889.

I write this because I cannot bear the silence any longer, and yet I can never speak these words aloud.

Elizabeth is dead, and I am the only one left who knows the full horror of what happened in our house.

But I am afraid, so terribly afraid.

The journal revealed a nightmare hidden behind Beacon Hill’s elegant facades.

After their father’s death in 1887, Elizabeth and Sarah had inherited the house in a significant debt.

Their father’s business partner, a man named Charles Whitmore, had offered a solution.

The house could be used for his private business, and in exchange, he would settle the debts and provide the sisters with a generous income.

Elizabeth had been desperate enough to agree, not knowing what Whitmore’s business truly entailed.

Young women, immigrants, and servants seeking employment were brought to the house under false pretenses.

Some were held there temporarily before being transported elsewhere.

Others disappeared entirely.

Elizabeth had discovered the truth too late.

By the time Elizabeth understood what we had become part of, she was terrified to go to the police.

Sarah wrote, “Whitore had made us complicit.

We had taken his money, allowed our home to be used.

He said if Elizabeth spoke, we would hang beside him.

But my sister could not live with the guilt.

She began documenting everything.

Names, dates, descriptions of the men who came to our house.

She planned to take her evidence to the authorities.

Consequences be damned.

Emma turned the page, her heart pounding.

On the night of April 12th, 1889, Whitmore came to our house.

I heard him arguing with Elizabeth in the hallway.

She told him she had already copied her evidence, that it was hidden where he would never find it.

And then I heard the scream and the terrible sound of her falling.

Catherine had tears streaming down her face.

He killed her.

Sarah’s journal continued detailing the aftermath of Elizabeth’s murder.

Whitmore had positioned it to look like an accidental fall.

Dr.

Webb, the family physician who signed the death certificate, was in Whitmore’s pocket.

The police investigation was prefuncter, discouraged from above by officials who had been bribed or threatened.

But Sarah wrote of one thing that terrified her more than anything.

3 weeks before her death, Elizabeth insisted we have a portrait made at Crawford Studios.

She said she wanted a record of us together while we were still ourselves.

I thought it strange at the time.

Why then, in the midst of her anguish, but now I understand, she was creating evidence.

She somehow ensured that Whitmore would be reflected in the mirror behind us.

She had arranged for him to be in the studio that day, hidden behind the photographer, watching us.

She captured his presence in the one place he thought he was invisible.

Emma gasped.

Elizabeth had known.

She had deliberately created a record that Whitmore was watching them, threatening them.

The photograph was never meant to be an innocent family portrait.

It was evidence.

Crawford developed the image and must have seen what Elizabeth intended.

Sarah’s journal continued.

He brought it to me privately after Elizabeth died.

Asked careful questions.

I was too frightened to speak.

I denied everything.

Two years later, I heard he had disappeared.

I believe Whitmore discovered that Crawford knew the truth.

He killed him just as he killed my sister.

The journal’s final entry was dated 1934, written in an elderly hand.

I have lived my entire life with this cowardice.

I could not save Elizabeth.

I could not save Crawford.

I could not save the women who disappeared into that house’s darkness.

Whitmore died wealthy and respected in 1912.

I’ve prayed for the courage to speak but never found it.

I leave this record as the only testimony I can give.

May God forgive me for my silent,” Emma closed the journal carefully.

The room was silent except for Catherine’s quiet weeping.

“What happens now?” Catherine finally asked.

Emma looked at the photograph at Elizabeth’s terrified eyes at the figure in the mirror behind them.

“Now we tell their story.

We give Elizabeth the justice she died trying to obtain and we named Charles Whitmore for what he was a murderer.

Three months later, Emma published her research.

The story went viral, a Victorian murder mystery solved by a reflection in a mirror.

Boston newspapers ran features.

The historical society mounted an exhibition.

Catherine donated Sarah’s journal to the state archives where it would be preserved as testimony to the women who vanished.

And the sister who finally postuously found her voice.

The house at 42 Mount Vernon Street received a historical marker detailing its dark past.

And in the exhibition, Elizabeth and Sarah’s portrait hung in a place of honor.

The mirror’s reflection finally revealing its secret to the world.

Elizabeth had created her own evidence, trapped her killer’s image in silver and glass.

It had taken 135 years, but her message had finally been received.

The photograph wasn’t just a portrait.

It was a witness and it had never stopped speaking.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load