It began with a photograph.

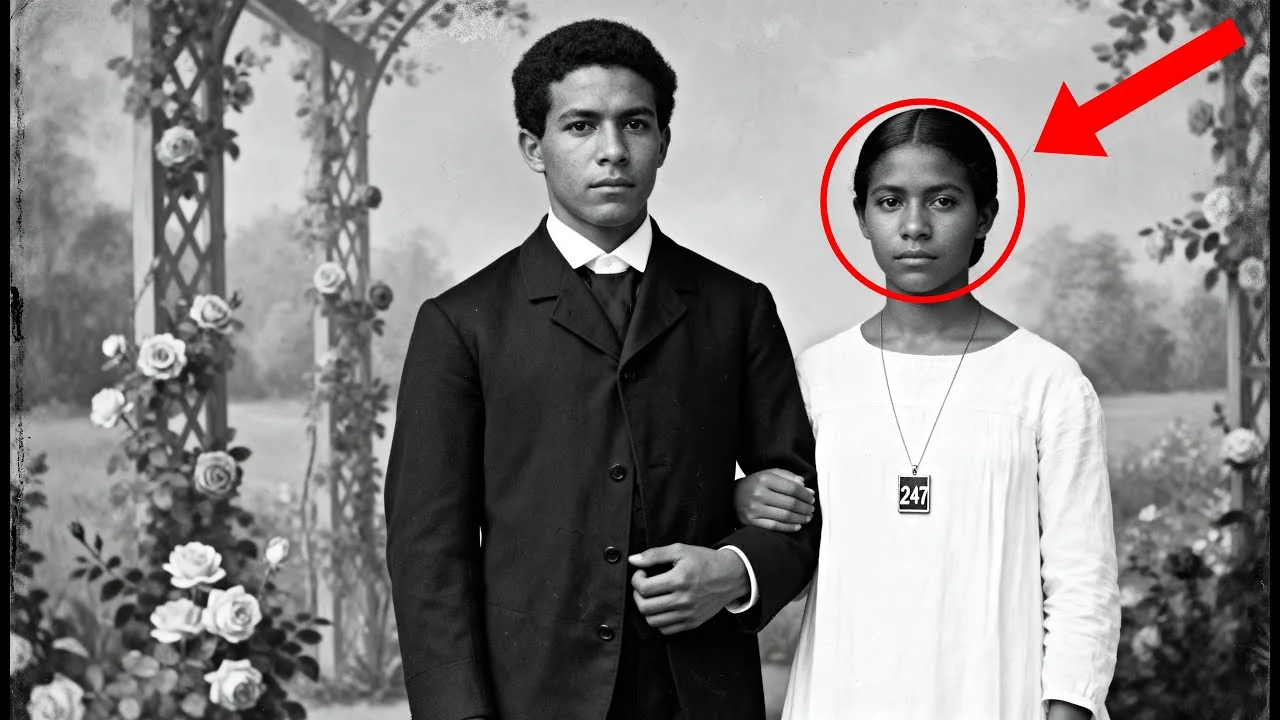

The image, sepia-toned and slightly faded, seemed to capture a moment of quiet celebration: a young couple, newly married, standing stiffly before an artificial garden backdrop in a Louisiana studio.

Their hands barely touch, their expressions unreadable—perhaps nervous, perhaps simply tired.

At first glance, it is a picture like countless others from the late 19th century, a testament to love and new beginnings.

But when Dr.

Sarah Mitchum, a historian with an eye for the unsettling, examined the photograph one spring afternoon in 2019, she noticed something that would unravel not just the story of this couple, but a hidden chapter in American history.

Around the bride’s neck, resting just below her collarbone, hung a pendant.

Not a locket, nor a cross, but a small rectangle of metal, engraved with a number: 247.

That number, stamped as cleanly as a brand on livestock, would lead Sarah on a journey through archives, court records, and family stories—a journey that would expose a system of bondage that survived long after emancipation, masquerading as charity, and trapping thousands of women in a cycle of debt and servitude.

A Closer Look: The Clue That Changed Everything

Sarah Mitchum was no stranger to the secrets buried in old photographs.

With fifteen years’ experience cataloging 19th-century images, she had learned to read the visual language of staged poses, borrowed clothes, and studio props that hinted at lives more complicated than the portraits suggested.

But she had never seen anything like the numbered pendant worn by the bride in the 1888 photo.

The couple, identified on the back as Selene and Thomas Brousard, had married in Nachitoches, Louisiana, on June 3rd, 1888.

The studio mark—Jay Lavo, Photographer—confirmed the date and place.

Yet the pendant defied explanation.

Wedding jewelry of the era was typically sentimental: monogrammed lockets, religious symbols, memorial pieces.

A plain number, worn on what should have been the most carefully composed photograph of a woman’s life, made no sense.

Sarah’s rule was simple: if something in an old photograph looked wrong, it usually was wrong.

Not supernatural, not a trick of the light, but wrong in the sense that it revealed something the people staging the image had either failed to notice or had chosen to ignore.

She set out to discover what that number meant.

The Benevolent Relief Society: Charity or Captivity?

Behind the photograph, tucked between the backing board and the frame, Sarah found a square of yellowed newsprint: an advertisement from May 1888.

It read:

Benevolent Relief Society of Nachitoches.

Loans available to respectable women of limited means.

Low interest.

References required.

Inquire at 142nd Street.

The ad seemed innocuous enough—a charitable offer to women in need.

But as Sarah dug deeper, the story grew darker.

A dissertation footnote led her to a court case from 1891, involving the Ladies Relief and Improvement Society of Nachitoches Parish.

A woman named Margarite Duce had borrowed twelve dollars for medical expenses, signing a contract that bound her to work for society members until the debt was repaid.

The terms were harsh: room and board, a small monthly credit toward the debt, penalties for missed work, and a requirement to wear an identification pendant at all times.

The judge ruled that Margarite had entered the contract willingly.

There was no record of whether she ever repaid the debt.

Sarah’s stomach turned as she realized what she had found: a system known as debt peonage, where charitable societies lent money to poor women, then bound them to labor contracts that were nearly impossible to escape.

The numbered pendant was not jewelry—it was a registry tag, a mark of a woman’s status as property.

A System Built on Respectability

To understand how such a system could exist, Sarah reached out to Dr.

Leon Forest, a historian at Louisiana State University.

Leon explained that after the Civil War, Louisiana became a laboratory for reinventing bondage under new names: convict leasing, sharecropping, apprenticeship laws, and for poor women—especially women of color—the benevolent societies.

“They presented themselves as charity,” Leon said, “but the contracts were designed to be inescapable.

The interest was low, but the penalties were not.

Miss a day of work because you’re sick, penalty.

Refuse an assignment, penalty.

Try to leave town, you could be arrested.”

The registry system, Leon explained, was a way to track debtors and ensure society members could identify contracted women on sight.

Some societies used badges, others armbands.

Pendants were more discreet, easier to explain away as ordinary jewelry.

How many women were trapped in this system? “Thousands,” Leon said, “across Louisiana and Mississippi, maybe more.

Most of the records were destroyed or sealed.

The societies disbanded in the 1890s when federal investigators started asking questions, but by then the damage was done.”

Selene’s Story: A Life Marked by Debt

Sarah traced Selene Brousard’s life through census records and church registers.

In 1880, Thomas Brousard was listed as a laborer, unmarried.

By 1900, he was a farmer, with Selene keeping house and two children, Marie and Julianne.

In 1910, Thomas remained, but Selene was gone—no death record, no explanation.

Church records at St.

Francis of Assisi revealed that Selene and Thomas had married in June 1888, as the photograph indicated.

A note in the margin of the marriage register, added later, read: Contract annulled September 1892. Not the marriage—the contract.

Selene Brousard was buried in October 1892, at age 24, in the pauper section of the parish cemetery.

Cause of death: fever.

No other details.

Uncovering the Hidden Economy

Sarah’s investigation uncovered dozens of contracts in parish records, each nearly identical: a small loan, an agreement to work for member families until the debt was repaid, a clause requiring the debtor to wear a registry pendant, and a provision stating that any attempt to abscond would result in criminal charges for theft of services.

The Benevolent Relief Society operated from a building now occupied by a dentist’s office.

Across the street, a historical marker noted that Nachitoches had been home to several charitable organizations, including the Ladies Relief and Improvement Society.

There was no mention of the contracts, the pendants, or the women who had died still wearing their numbers.

Confronting the Past

When Sarah presented her findings to the historical society board, the response was mixed.

Some members argued for caution, worried about alienating donors and challenging the reputations of prominent families.

Others insisted that the evidence demanded honesty.

“This is not interpretation,” Sarah said.

“These are legal contracts filed with the parish, signed by real women.

Women like Selene Brousard, who was contracted at 17, married at 20, and dead at 24, still wearing the number the society gave her.”

The board voted to approve a special exhibition centered on the Brousard photograph and the system of debt peonage it revealed.

Sarah was warned to be prepared for backlash.

Telling the Truth: The Exhibition and Its Impact

Sarah spent three months building the exhibition, working with designers and scholars to provide context: maps showing the locations of benevolent societies, copies of contracts, court cases, testimonies from women who had challenged the system and lost.

Dr.

Felicia Batist, a sociologist at Xavier University, contributed an essay analyzing how benevolent societies weaponized respectability and charity to create a system of control more insidious than slavery because it disguised itself as compassion.

Descendants of contracted women began to come forward, sharing family stories and documents they had kept hidden out of shame.

Teresa Gidri brought in a pendant identical to the one in the Brousard photograph, numbered 198.

“I always thought it was strange,” she said, “but I didn’t know what it meant.

Now I do.”

The exhibition, originally scheduled to close in December, was extended through the spring.

Requests came from museums and researchers across the country.

The photograph of Selene and Thomas Brousard now appears in textbooks and exhibitions, always accompanied by an explanation of what the pendant means—and by the broader context of the benevolent societies that trapped thousands of women in a cycle of debt and servitude.

The Legacy: What Do We Choose to See?

For decades, people looked at the Brousard photograph and saw a sweet wedding portrait.

They saw what they expected to see.

They did not see the number.

But once you know it is there, you cannot unsee it.

And once you understand what it means, you start to wonder what else you have been missing.

How many other portraits contain evidence of violence disguised as virtue? How many other families built their respectability on the backs of women who had no choice but to wear their numbers and smile for the camera?

Selene Brousard was contracted at 17, married at 20, and dead at 24.

She wore her number on her wedding day because she had no choice.

And the photograph that was meant to commemorate her marriage became instead evidence of a system that treated her not as a bride, but as property.

The camera captured what it always captures: the truth, whether anyone was ready to see it or not.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load