The truth behind the portrait of these five siblings is more tragic than anyone imagined.

Daniel Rivers had been working as a digital archivist for the Philadelphia Historical Preservation Society for 8 years, and he thought he had seen every type of old photograph imaginable.

But the image that arrived on his desk on a cold November morning in 2024 made him pause midsip of his coffee.

The photograph had been discovered during the demolition of an abandoned Victorian rowhouse in the Fairmount neighborhood.

A construction worker had found it wedged behind a loose baseboard in what had once been a nursery, wrapped in oil cloth, and remarkably well preserved, despite spending over a century hidden in a wall cavity.

Daniel carefully unwrapped the protective cloth, revealing an ornate silver frame, tarnished with age, but still bearing intricate floral engravings along its borders.

The photograph inside was mounted on heavy cardboard backing, typical of professional studio portraits from the 1880s.

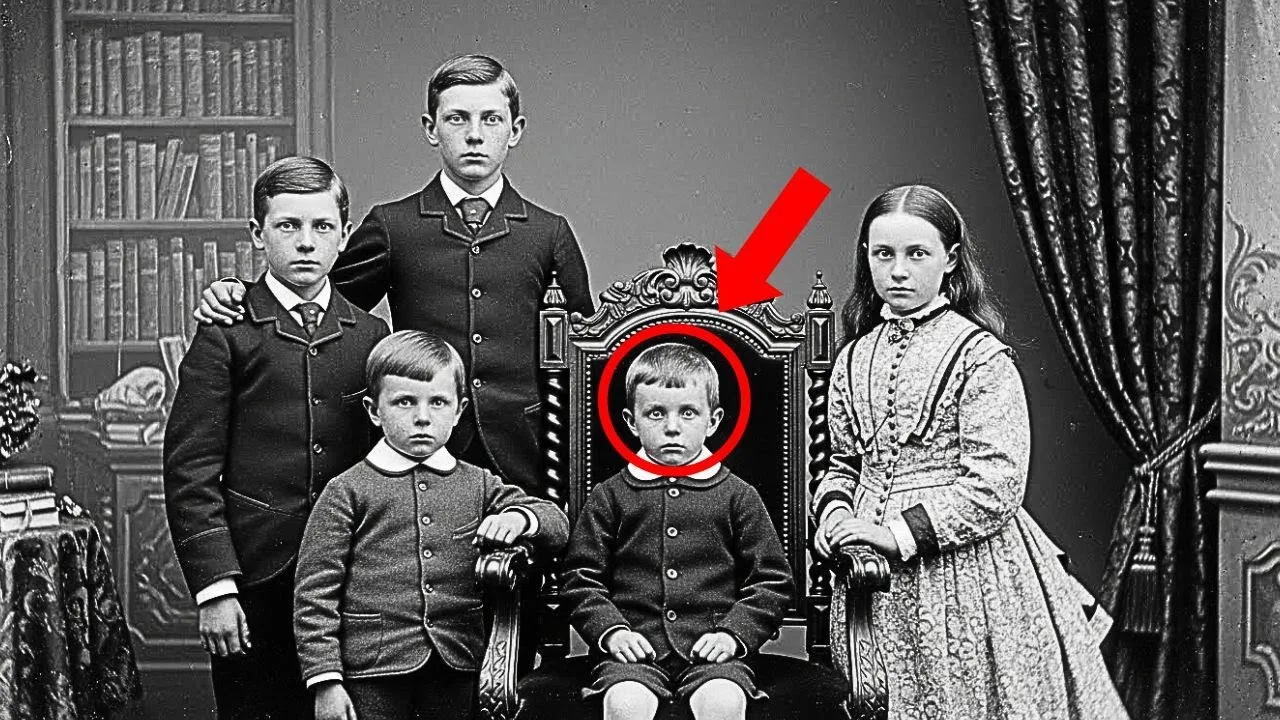

The image showed five children arranged in a carefully composed group portrait, their Victorian era clothing suggesting wealth and social standing.

The setting was a professional photographers’s studio, evident from the painted backdrop depicting a library with leather-bound books and heavy velvet curtains.

The lighting was dramatic and skillfully executed, creating depth and dimension that was impressive for the era.

Four boys and one girl, ranging in age from approximately 6 to 14 years old, were positioned in a pyramidal composition.

The oldest boy, perhaps 13 or 14, stood at the back left, his hand resting protectively on the shoulder of a younger boy beside him.

To the right stood another boy of similar age, maybe 12, his posture ramrod straight and formal.

In the center, seated in an ornate wooden chair, was a younger boy who appeared to be about 8 years old, wearing a velvet suit with a lace collar.

The only girl around 10 years old stood to his right, her hand touching the back of his chair, her elaborate dress with its high collar and puffed sleeves indicating the family’s prosperity.

What struck Daniel immediately was the expressions on their faces.

Victorian photographs typically showed subjects with stern, serious expressions.

Partly due to the long exposure times required, partly due to cultural conventions about dignity and formality.

But these children looked beyond serious.

They looked devastated.

The three standing siblings had eyes rimmed with redness as if they had been crying recently.

Their faces were drawn, hollow with what appeared to be exhaustion or profound sadness.

The girl’s hand on the chair wasn’t just resting there.

Her fingers were gripping the wood tightly, knuckles white, even in the sepia tones of the old photograph.

But it was the youngest boy in the center that drew Daniel’s attention.

Something about him was different.

Daniel wheeled his chair closer to the examination table and switched on the high-powered magnifying lamp.

He had learned over years of archival work that old photographs often revealed their secrets only under careful scrutiny.

As the bright light illuminated the image, details that had been obscured by age and shadow became clearer.

The seated boy’s posture was unnaturally rigid.

His back perfectly straight in a way that seemed almost impossible for a child of that age.

His hands were positioned precisely on his lap, fingers arranged too perfectly, as if they had been carefully placed and had not moved since.

Most tellingly, his eyes had a peculiar quality.

They were open, but there was a flatness to them, an absence that made Daniel’s stomach tighten with realization.

He had seen this before, though rarely.

This was a post-mortem photograph.

Daniel leaned back, processing what he was looking at.

Post-mortem photography had been a common practice in the Victorian era, a way for families to preserve the image of deceased loved ones, particularly children who died before affordable photography became widespread.

But there was something unusual about this particular image that he couldn’t quite articulate yet.

He turned the frame over carefully, looking for any identifying marks or inscriptions.

On the back of the frame, engraved an elegant script on a small brass plate, were the words, “The Witmore children, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, March 12th, 1887.” Below that, in smaller handscratched letters that appeared to have been added later, someone had etched together always for Thomas.

Thomas, the boy in the center, must be Thomas.

Daniel photographed the inscription with his phone, then carefully removed the backing from the frame to examine the photograph more closely.

As he lifted the image from its mounting, a small envelope fell out, yellowed with age and sealed with red wax that had cracked but not broken.

His hands trembled slightly as he picked it up.

The envelope was addressed in a child’s careful handwriting.

To whoever finds this photograph, please read.

It’s important.

Daniel’s heart raced.

In 8 years of archival work, he had never encountered anything quite like this.

He grabbed a letter opener and carefully broke the wax seal, extracting two sheets of paper covered in faded ink written in the same youthful hand.

The letter began, “My name is William Whitmore.

I am 14 years old.

The boy sitting in the center of this photograph is my brother Thomas.

He died yesterday of scarlet fever.

He was 8 years old and he was the best of all of us.

Daniel’s hands shook as he continued reading the letter written over 137 years ago by a grieving teenage boy.

Mother and father are destroyed by grief and cannot function.

They have locked themselves in their bedroom and will see no one, not even us.

The doctor says Thomas died quickly.

The fever took him in just 2 days.

One morning he was laughing at breakfast, complaining about his Latin lessons, and by the next evening he was gone.

We never got to say goodbye properly.

He was unconscious at the end.

My brothers, Samuel, 12, and me, and our sister, Catherine, 10, and our youngest brother, James, 6, we made a decision together.

We couldn’t let Thomas be buried without one more family portrait.

We couldn’t let him disappear without proof that he was ours, that he belonged with us, that we loved him more than anything in the world.

We took our savings, money we’d been collecting for a year to buy father a new pipe for his birthday, and we went to Mr.

Ashford’s photography studio on Chestnut Street.

We brought Thomas with us.

Catherine stayed with him all night before, making sure he looked perfect, combing his hair, dressing him in his best velvet suit, the one he wore to church on Sundays.

Mr.

Ashford didn’t want to do it at first.

He said it wasn’t proper for children to arrange such things, that our parents should be involved.

But Catherine cried and begged him.

She told him that Thomas loved us more than anyone, that we were his world, and that he would want to be photographed with us, not with adults who were too griefstricken to even look at him.

Finally, Mr.

Ashford agreed.

He was very kind.

He helped us position Thomas in the chair, placed supports behind him so he would sit upright.

He arranged our hands, told us where to stand.

He said we could touch Thomas, that it was all right to hold on to him one last time.

So, Catherine put her hand on his chair and I put my hand on Samuel’s shoulder and Samuel stood close to Thomas and James, little James, who didn’t fully understand that Thomas was really gone forever.

James, just stood there crying silently the whole time.

Mr.

Ashford, told us to look at the camera, but we couldn’t.

We could only look at Thomas.

We wanted to remember him exactly as he was in that moment, dressed beautifully, sitting with us, part of our family.

The photograph took nearly 30 seconds.

Mr.

Ashford said we had to stay perfectly still or it would be blurred.

It was the hardest thing I’ve ever done, standing there motionless while my heart was breaking, while my little brother sat dead in front of me, while Catherine’s hand trembled on that chair.

After it was done, Mr.

Ashford told us he would have the photograph ready in 3 days, but by then Thomas would already be buried.

We asked him if we could wait if he could develop it immediately.

He saw how desperate we were and agreed.

We waited in his studio for 4 hours while he worked in his dark room.

Catherine held James.

Samuel and I sat in silence, unable to speak.

When Mr.

After Ashford finally brought us the photograph mounted in this silver frame, we all started crying again.

There was Thomas, looking almost alive, sitting with us one last time.

It was worth every penny we had saved.

Daniel paused in his reading, tears blurring his vision.

The letter continued on the second page.

Daniel wiped his eyes and continued reading William’s letter.

We brought the photograph home and showed it to mother and father.

Mother collapsed when she saw it.

She screamed at us, called us morbid and unnatural, said we had desecrated Thomas’s memory by playing with his body like a doll.

Father said nothing.

He just turned away and went back to his room.

Mother ordered us to destroy the photograph to burn it and never speak of it again.

But we couldn’t.

We had spent everything we had to create this one last memory of all five of us together.

So, we hid it.

We took turns keeping it safe, moving it between our rooms, showing it to each other late at night when mother and father were asleep.

It was our secret, our treasure, our proof that Thomas had existed and that we had loved him.

Thomas died on March 11th, 1887.

We took this photograph on March 12th, the day after his death, the day before his funeral.

I am writing this letter on March 15th, 1887, 3 days later.

I am hiding it behind this photograph because I want whoever finds it someday to know the truth.

This photograph was not made by griefstricken parents trying to preserve their child’s memory.

It was made by children who refused to let their brother disappear without one final moment of being together.

Thomas was funny and kind and brave.

He once climbed the tallest tree in Writtenhouse Square on a dare and got stuck for 2 hours until the fire brigade came.

He collected beetles and jars and gave them names.

He could recite entire passages from Robinson Crusoe from memory.

He wanted to be a ship captain when he grew up and sailed to China.

He hated Brussels sprouts and loved lemon cake.

He had a crooked front tooth from when he fell off his bicycle last summer.

He laughed so hard at jokes that he would snort, which made the rest of us laugh even harder.

He was real.

He was ours.

He was loved.

And now he is gone.

And this photograph is all we have left of him being with us.

If you find this, please don’t destroy it.

Please understand that it was made with love, not with morbid fascination.

We were just children trying to hold on to our brother for one more moment.

We were just children who couldn’t bear to say goodbye.

William Whitmore, age 14, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, March 15th, 1887 PS.

Catherine wants me to add that Thomas’s favorite color was blue and that he always shared his candy with James, even though James was too young to properly appreciate it.

Samuel wants me to add that Thomas was the fastest runner of all of us.

James doesn’t understand enough to add anything, but he keeps asking when Thomas is coming home.

I don’t know how to tell him that Thomas is never coming home.

Daniel sat motionless at his desk, the letter trembling in his hands.

This wasn’t just a post-mortem photograph.

This was a monument to sibling love.

A desperate act of children refusing to let go of their brother.

A rebellion against adult grief that had paralyzed their parents.

He had to know what happened to these children.

He had to find out if they had survived their own grief.

If that photograph had given them what they needed, or if it had haunted them for the rest of their lives.

Daniel spent the remainder of the day searching through the historical society’s archives for any information about the Witmore family of Philadelphia.

The name was common enough that he found dozens of entries, but cross-referencing with the date of 1887 and the neighborhood where the house had been found narrowed it down significantly.

In the 1880 federal census, he found them.

Jonathan Whitmore, age 35, occupation listed as banker.

His wife Elizabeth, age 32, and their children, William, born 1873, Samuel, born 1875, Catherine, born 1877, Thomas, born 1879, and James, born 1881.

The family lived on Delansancy Street in a fashionable part of Philadelphia, consistent with Jonathan’s profession.

Daniel then searched for Thomas’s death certificate.

It took an hour of scrolling through records, but he finally found it.

Thomas Witmore, age 8, died March 11th, 1887.

Cause of death listed as scarlet fever, acute.

The certificate was signed by Dr.

Henry Morrison, a prominent Philadelphia physician of the era.

Scarlet fever had been one of the most feared childhood diseases of the 19th century.

caused by streptocockal bacteria.

It spread rapidly through households and communities, particularly affecting children between the ages of five and 15.

The characteristic red rash, high fever, and throat inflammation could progress quickly to kidney damage, rheumatic fever, and death.

There was no effective treatment until the development of antibiotics in the 1940s.

Daniel found records of a significant scarlet fever outbreak in Philadelphia during the winter of 1887.

With dozens of children dying across the city in February and March, Thomas had been one of many victims.

But what happened to the surviving siblings? Daniel searched through city directories, census records, and newspaper archives, building a timeline of the Witmore family after Thomas’s death.

The 1890 census showed the family still living on Delansancy Street, but now listed as only six members instead of seven.

By the 1900 census, things had changed dramatically.

Jonathan and Elizabeth Whitmore were still at the same address, but only one child remained with them.

James, now 19 years old.

William, Samuel, and Catherine were gone.

Daniel dug deeper, searching through property records, marriage certificates, and business directories.

What he discovered was a family that had fractured after Thomas’s death.

Each member coping with grief in different ways.

William Whitmore had left Philadelphia in 1889 at age 16.

According to a brief mention in a shipping company’s employment records, he had signed on as a cabin boy aboard a merchant vessel bound for South America, apparently making good on Thomas’s dream of sailing to distant shores.

Samuel Witmore’s trail was more troubling.

Daniel found his name in the registry of the Pennsylvania Institution for the Instruction of the Blind, admitted in 1891 at age 16.

A medical note indicated he had suffered from hysterical blindness following severe emotional trauma.

The condition, now recognized as a psychosmatic response to unbearable stress, had apparently been triggered by his brother’s death.

Catherine’s story emerged from a different source entirely.

While searching through the archives of St.

E Mary’s Catholic Church in Philadelphia.

Daniel found her name in the registry of women who had entered the convent of the Sisters of Mercy in 1893 at just 16 years old.

She had taken the religious name Sister Mary Thomas.

The pattern was becoming clear.

Each of the surviving siblings had in their own way fled from the trauma of Thomas’s death and the photograph they had created.

William had literally sailed away.

Samuel had lost his sight, perhaps unable to bear seeing a world without his younger brother.

Catherine had sought refuge in religious devotion, taking Thomas’s name as her own, as if to keep him alive through her.

But what about James, the youngest? Daniel returned to the census records and city directories, tracking him through the decades.

James had stayed in Philadelphia, living with his parents until their deaths.

Jonathan in 1904, Elizabeth in 1908.

After that, James had moved to a modest apartment in the Germantown neighborhood and worked as a clerk in a law office.

Daniel found something unexpected in the archives of the Philadelphia Inquirer from 1925, a small article about a charity exhibition of Victorian photography at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

The exhibition had been organized by James Whitmore, described as a collector of antique photographs.

The article mentioned that Whitmore had donated several pieces to the exhibition, including a poignant family portrait from 1887.

James had kept the photograph.

After all those years, 38 years since Thomas’s death, he had still possessed the image that had caused so much turmoil in his family.

Daniel knew he needed to find out more about James.

He was the only sibling who had remained in Philadelphia, the only one who had kept the photograph.

Perhaps he had also kept other records, letters, or documents that might shed light on what that image had meant to the children who created it.

The trail led to the archives of Laurel Hill Cemetery, where Daniel discovered burial records for the Whitmore family.

Jonathan and Elizabeth were interred there, as was Thomas, his small gravestone listing only his name, dates, and the words, “Our beloved son.” But there was also a grave for James Whitmore, who had died in 1947 at age 66.

What caught Daniel’s attention was a note in the cemetery’s records indicating that James’ burial plot had an unusual feature.

He had been interred with a sealed metal box containing personal effects per the deceased’s specific instructions.

Daniel felt a surge of excitement.

Cemetery records from that era sometimes included inventories of such items, especially if they were valuable or unusual.

He requested access to Laurel Hills historical archives, explaining his research into the Witmore family photograph.

The archavist, an elderly woman named Helen, listened to his story with growing interest.

The Witmore plot, she said thoughtfully.

I know it.

My predecessor mentioned it in her notes.

said there was something unusual about the burial arrangements.

“Let me check our records.” She disappeared into the back room and returned 20 minutes later, carrying a leatherbound ledger.

“Here,” she said, opening it to a page marked with a ribbon.

“James Whitmore’s burial record from June 1947.” “Daniel leaned over the ledger, reading the faded handwriting.

The burial record was detailed, listing not just the basic information, but also notes from the cemetery director about James’s specific requests.

One passage made Daniel’s heart race.

The deceased requested that a sealed tin box be placed in his casket positioned over his heart.

The box, approximately 8 in x 10 in, contains what Mr.

Whitmore described in his will as letters and a photograph that must stay with me.

His attorney, Mr.

Peter Townsend verified that this was the deceased’s explicit final wish.

The box was sealed in my presence and will not be opened.

Mr.

Whitmore left a letter with his attorney to be opened only if the family plot is ever relocated or disturbed, explaining the contents of the box.

Is the attorney’s letter still on file? Daniel asked Helen, trying to keep his voice steady.

If it exists, it would be with the Towns End Family Law Firm.

They’ve been handling estate matters in Philadelphia for over a hundred years, but I don’t know if they still have records from 1947.

Daniel thanked Helen and immediately began researching the Towns and firm.

To his relief, the firm still existed, now called Townsend and Associates, operating from a historic building on Walnut Street.

He called and explained his research into the Whitmore family, asking if they had any archived documents related to James Whitmore’s estate.

The receptionist was skeptical until Daniel mentioned the sealed letter meant to explain the contents of the tin box.

Hold on, she said.

Let me check with our senior partner.

He’s the one who maintains our historical archives.

After a 10-minute wait, an older man’s voice came on the line.

This is Richard Townsend.

You’re asking about James Whitmore’s estate from 1947.

Yes, sir.

I’m researching a Victorian photograph that belonged to the Witmore family and I have reason to believe James left instructions about it.

There was a long pause.

The sealed letter, Townsen said finally, “My grandfather, Peter Townsend, was James’ attorney.

He kept meticulous records and I inherited his archives when I took over the firm.

The Witmore file is still here.

James’ letter has never been opened because the conditions for opening it were never met.

The family plot was never relocated or disturbed.

“Would you be willing to meet with me?” Daniel asked.

“I have the photograph and a letter written by James’ brother, William, from 1887.

I think you’ll want to see them.” The next morning, Daniel arrived at Townsend and Associates carrying a carefully wrapped box containing the photograph and Williams letter.

Richard Townsend was a distinguished man in his 70s with silver hair and the careful manner of someone who had spent a lifetime handling sensitive documents.

Before we proceed, Townsen said, leading Daniel into a private conference room, “You should understand that James Whitmore was a client of my grandfathers for over 30 years.

My grandfather spoke of him often, said he was one of the saddest men he’d ever known.

whatever is in that letter and that photograph clearly haunted James his entire life.

Daniel unwrapped the photograph and placed it on the conference table along with William’s letter.

Townsen put on reading glasses and examined both carefully, his expression growing increasingly moved as he read William’s words.

“My God,” Townsen said softly.

“These children, they lost their brother and then lost each other.” Richard Townsen stood and walked to a large safe in the corner of the conference room.

He worked the combination, opened it, and withdrew a thin Manila folder labeled Witmore James Estate, 1947, sealed.

Inside was a single envelope yellowed with age with instructions written on the front to be opened only if the Witmore family plot at Laurel Hill Cemetery is relocated or disturbed or at the discretion of a Towns and partner if compelling circumstances arise.

Townsend looked at Daniel.

I believe these are compelling circumstances.

James wanted this story told under the right conditions.

You found the photograph.

You’ve researched the family.

and you have William’s original letter.

That’s more than compelling.

That’s fate.

He carefully broke the seal and extracted several pages of typed text dated May 1947, written by James in the last month of his life.

Towns and began reading aloud.

My name is James Whitmore.

I am 66 years old, dying of heart disease, and I have carried a secret my entire life.

A secret that has shaped everything I am and everything I failed to become.

If you are reading this, then somehow the photograph has resurfaced and someone cares enough to seek the truth.

Thank you for that.

My brother Thomas died when I was 6 years old.

I was too young to fully understand death.

Too young to process the enormity of what we had lost.

I only knew that Thomas, who had read me stories and taught me to tie my shoes and shared his candy with me, was suddenly gone.

And everyone in the house was crying and no one would explain why he wasn’t coming back.

My older siblings, William, Samuel, and Catherine, made a decision that would haunt all of us for the rest of our lives.

They took me with them to have a photograph made with Thomas’s body.

I remember being confused about why Thomas was so quiet, why he wouldn’t answer when I talked to him.

Catherine kept shushing me, telling me to stand still, to be quiet, to look at the camera.

But I couldn’t look at the camera.

I could only look at Thomas, wondering why he wouldn’t look back at me.

When mother saw the photograph, she became hysterical.

She screamed at William, called him cruel and unnatural.

She slapped Catherine across the face and locked herself in her room for 3 days.

Father said nothing.

He never spoke of Thomas again, not once in the 20 years he lived after that day.

It was as if Thomas had been erased from our family, as if he had never existed at all.

The photograph became a source of shame and guilt.

William ran away to see when he was 16.

Catherine entered a convent at 16.

Samuel, poor Samuel, went blind from what the doctors called hysteria.

I believe he couldn’t bear to see the world anymore.

Couldn’t bear to see that photograph every time he closed his eyes.

I was the only one who stayed.

I stayed because I was young.

Because I had nowhere else to go.

because someone had to remember.

Over the years, my siblings drifted away from each other and from me.

William wrote once from Brazil, then never again.

Catherine’s letters from the convent were brief and formal, full of prayers, but empty of feeling.

Samuel lived at the institution for the blind until his death in 1932, and I visited him every month, though he never wanted to talk about Thomas or the photograph.

But I kept the photograph.

I hid it, moved it, protected it through my parents’ deaths, through decades of living alone.

Through the guilt and the grief that never truly faded, because despite everything, despite the pain it caused, despite the family it destroyed, that photograph was the truth.

It was proof that we had loved Thomas, that we had tried in our childish, desperate way to hold on to him for one more moment.

Daniel listened, tears streaming down his face as Townsend continued reading.

Townsend’s voice grew thick with emotion as he read the final pages of James’s letter.

I want whoever finds this photograph to understand something important.

We were not morbid children.

We were not unnatural or cruel.

We were heartbroken, terrified children who couldn’t accept that our brother was gone.

We wanted one more moment with him.

We wanted proof that he had existed, that he had been loved, that he had mattered.

Our parents’ reaction taught us that our grief was wrong, that our attempt to honor Thomas was shameful, so we each fled from it in our own way.

William sailed away to places where no one knew about Thomas.

Catherine disappeared into religious devotion, perhaps seeking forgiveness for something that never required forgiveness.

Samuel lost his sight rather than continue seeing a world without Thomas in it.

And I stayed, carrying the weight of all our grief, unable to let go of the photograph because letting go would mean losing Thomas all over again.

I am dying now and I am taking this photograph with me.

I am being buried with it placed over my heart along with every letter my siblings ever wrote to me.

The few letters William sent before he stopped writing.

the formal notes from Catherine at the convent, the heartbreaking messages from Samuel at the institution.

We were five and then we were four and then we scattered to the winds and now I am the last one left.

If this letter is being read, it means the photograph has been found.

Please don’t judge us harshly.

We were children who loved our brother and didn’t know how to say goodbye.

We created something that our parents saw as monstrous.

But to us, it was love made visible.

It was our way of saying Thomas was here.

Thomas was ours.

Thomas mattered.

I have lived 60 years since that photograph was taken.

I never married, never had children of my own.

How could I? Every time I looked at a child, I saw Thomas’s face.

Every time someone smiled, I remembered his laugh.

Every time I heard children playing, I remembered the games we used to play, all five of us, before Scarlet Fever took him away.

The photograph didn’t destroy our family.

Thomas’s death destroyed our family.

The photograph was just our last desperate attempt to keep him with us.

Our parents couldn’t understand that.

They saw only the Macob practice of photographing a dead child.

They couldn’t see the love, the refusal to let go, the children’s belief that somehow if we could capture Thomas in a photograph with all of us, he wouldn’t really be gone.

We were wrong.

Of course, Thomas was gone.

The photograph couldn’t bring him back.

But it did give us one thing.

Proof that our love was real.

That our grief was valid.

that Thomas had been here and had been loved fiercely by four siblings who would have done anything, even the unthinkable, to keep him with us a little longer.

I hope whoever reads this will preserve the photograph and tell our story.

Not as a cautionary tale about morbid Victorian practices, but as a story about love, imperfect, desperate, child-sized love that couldn’t save Thomas, but tried anyway.

We were the Witmore children.

We were five, then four, and we loved our brother more than we feared the judgment of the world.

James Whitmore, May 1947.

Townsen finished reading and carefully placed the letter on the table.

The room was silent except for the ticking of an antique clock on the wall.

3 months later, Daniel stood in a gallery at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, preparing for the opening of an exhibition he had spent weeks curating, Love and Loss: The Witmore Children, and Victorian Grief.

The photograph of the five siblings was displayed in a special climate controlled case, illuminated carefully to show every detail without causing damage to the fragile image.

Beside it were Williams letter from 1887 and James’ letter from 1947.

both professionally preserved and displayed under glass.

Daniel had also included context, information about scarlet fever outbreaks in 1887 Philadelphia, examples of other post-mortem photographs from the era, and historical documents about Victorian mourning practices.

But what made the exhibition truly powerful were the additional discoveries Daniel had made while researching the surviving siblings through ship manifests and South American archives.

He had tracked William’s journey.

William had indeed become a sailor, spending 40 years at sea before dying in Rio de Janeiro in 1929.

In his effects found by the British consul was a small watercolor painting of five children playing under a tree, clearly painted from memory, clearly depicting the Witmore siblings before tragedy struck.

Samuel’s story was preserved in the records of the Pennsylvania Institution for the Blind, where Daniel discovered that despite his blindness, Samuel had become a music teacher, working with blind children for 30 years.

His students remembered him as gentle and patient, and several of their testimonials mentioned that he often spoke of a younger brother who had loved music.

Samuel had died in 1932, having taught hundreds of children to find joy in a world they couldn’t see.

Catherine’s letters from the convent, which James had preserved and which were buried with him, revealed a woman who had devoted her life to caring for sick children in the convent’s orphanage.

As Sister Mary Thomas, she had spent 50 years providing comfort to children suffering from diseases like the one that had taken her brother.

She died in 1943, surrounded by children she had helped raise, having transformed her grief into a lifetime of compassion.

The exhibition opening drew a large crowd.

Historians, photographers, families with children, people interested in Victorian culture.

But what moved Daniel most were the parents who came with their own children, who stood before the photograph and explained gently to their sons and daughters about love and loss, and the ways people try to hold on to those they’ve lost.

One woman, in her 80s, stood before the photograph for nearly 30 minutes, tears streaming down her face.

Finally, she approached Daniel.

“I lost my younger sister when I was 12,” she said quietly.

“She was 8, the same age as Thomas.

My parents wouldn’t talk about her, wouldn’t keep photos of her displayed, said we needed to move forward, but I never forgot her.

I never stopped missing her.” Seeing this, seeing that other children felt what I felt, that they tried so desperately to hold on, it helps.

It makes me feel less alone.

Richard Townsend attended the opening, bringing with him several other members of Philadelphia’s legal and historical community.

He stood beside Daniel, looking at the photograph of the five Witmore children.

James would have wanted this, Townsen said.

He carried their story alone for 60 years.

Now others can carry it with him.

Daniel had arranged for the photograph to be permanently donated to the museum along with both letters and all the research he had compiled about the Witmore family.

A plaque beside the display read, “The Witmore children, 1887.” This photograph was created by four grieving siblings the day after their brother Thomas died of scarlet fever.

Against their parents’ wishes, William, 14, Samuel, 12, Catherine, 10, and James, 6, used their savings to commission a final portrait with Thomas.

Their act of love was misunderstood as morbid, leading to the fracturing of their family.

But their devotion to Thomas shaped their entire lives.

William sailed the world Thomas dreamed of seeing.

Samuel taught music to children who couldn’t see.

Catherine cared for sick orphans.

and James preserved this photograph for 60 years.

They were children who refused to let their brother be forgotten.

This is their story of love, loss, and the desperate things we do to hold on to those we’ve lost.

As the evening wound down and visitors began to leave, Daniel remained alone with the photograph.

He looked at the five faces, four living, one dead, all of them suspended in that impossible moment of grief and love.

He thought about William sailing to distant shores, carrying Thomas’s dream with him.

About Samuel teaching blind children to hear beauty and darkness.

About Catherine becoming the mother figure to hundreds of orphans.

Each one receiving the love she couldn’t give to Thomas.

About James living alone for 60 years, protecting this photograph like a sacred relic, unable to let go because letting go meant losing Thomas all over again.

The truth behind the portrait of these five siblings was indeed more tragic than anyone had imagined, but it was also more beautiful.

It was a testament to sibling love so fierce that it defied social conventions, parental disapproval, and the judgment of an entire era.

It was proof that sometimes the most profound acts of love are the ones that are misunderstood, the ones that seem strange or morbid to others, but are in fact desperate attempts to hold on to light in the darkest moments of our lives.

Daniel turned off the gallery lights, leaving only the soft illumination on the photograph.

The five Whitmore children gazed out from 1887, frozen in that moment of impossible love.

together one last time.

Just as they had wanted, just as they had fought for, just as they deserve to be remembered.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load