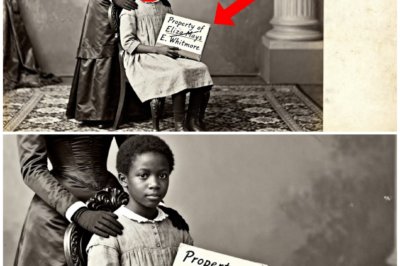

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers.

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud.

It looks triumphant.

It looks like the kind of image a family would frame and hang over a mantelpiece for a hundred years until you notice the lamp numbers.

At first glance, there’s nothing wrong with this photograph.

Two men stand shouldertosh shoulder in a photographer’s studio somewhere in eastern Kentucky, their faces stre with coal dust that no amount of scrubbing could entirely remove.

They hold their helmets against their chests like soldiers holding their caps.

Their expressions are solemn but steady.

They have survived another day underground, and they want the camera to know it.

But something about this image refused to let go of the woman who found it.

Her name is Margaret Callaway.

She has worked as an archivist at a regional history museum in Lexington for nearly 18 years.

And in that time, she has processed thousands of photographs from the coal fields of Appalachia.

[snorts] She knows what these images typically look like.

She knows how miners posed, what they wore, how they arranged their tools and equipment for the camera.

She has seen so many of these portraits that they have become, in her own words, almost invisible.

Just another part of the visual furniture of the region’s past.

This photograph arrived in a cardboard box donated by the estate of a retired school teacher in Harland County.

The school teacher had died without children, and her nephew, who lived in Ohio and had no particular interest in Kentucky history, had shipped the contents of her attic to the museum rather than throw them away.

Most of what arrived was unremarkable.

old yearbooks, church bulletins, a few amateur watercolors of mountain landscapes, and at the bottom of the box, wrapped in a deteriorating silk scarf, was this photograph.

Margaret almost set it aside with the others, almost.

But something made her look closer.

She cannot explain exactly what it was.

Maybe it was the way the two men stood, their bodies angled slightly toward each other as if they were brothers or close friends.

Maybe it was the quality of the print, which was sharper than most surviving images from that era.

Or maybe it was just the accumulated instinct of nearly two decades spent staring at old photographs, a sense that something in this particular frame did not quite add up.

She adjusted her desk lamp.

She pulled out her magnifying loop, and she looked at the helmets the two men were holding.

Each helmet had a small brass lamp attached to the front.

This was standard equipment for coal miners in the 1880s.

The lamps burned oil and provided the only light a man would have hundreds of feet below the surface of the earth.

And on each lamp, barely visible in the photograph, but unmistakable under magnification, was a small metal tag stamped with a number.

The man on the left held a lamp numbered 14.

The man on the right held a lamp numbered 31.

and Margaret.

Callaway felt a cold sensation spread through her chest because she knew exactly what those numbers meant.

Those were not their lamps.

In the coal mines of 19th century Kentucky, lamp numbers were assigned to individual workers.

The system served a practical purpose.

When a man entered the mine at the start of his shift, he collected his numbered lamp from a rack at the entrance.

When he emerged at the end of the shift, he returned the lamp to the same spot.

The foreman could look at the rack and know instantly who was still underground.

If a lamp was missing, a man was missing.

It was a simple, brutal form of accountability in an industry where men disappeared regularly.

But these two men were holding lamps with numbers that did not match.

And in Margaret’s experience, that could only mean one thing.

These lamps had been borrowed from men who would never use them again.

Margaret Callaway did not come to this work by accident.

She grew up in a coal town herself, a place called McRoberts in Lecher County, where her grandfather had worked underground for 30 years.

And her father had done the same until Black Lung forced him to retire early.

She remembers the sound of the mine whistle that marked the shifts, the way the whole town would grow quiet when it blew at an unexpected hour.

She remembers the funerals.

There were always funerals.

She went to college to study history.

And she came back to Kentucky because she believed that the stories of the coal fields deserve to be preserved.

Not the sanitized stories that appeared in company promotional materials or the nostalgic stories that politicians told when they wanted votes.

The real stories, the ones that showed what this industry had actually cost the people who built it.

So when she looked at those mismatched lamp numbers, she did not see a minor anomaly or a curious detail.

She saw a door and she knew she had to open it.

She started with the photograph itself.

She turned it over carefully and found a faded inscription in pencil on the back.

It read in a shaky hand T.

Puit and J.

Burke, Canel City, 1885.

Beneath that, in different handwriting, someone had added the words survived the collapse.

Canel City.

Margaret knew the name.

It was a small mining settlement in Morgan County about 60 mi east of Lexington.

The town barely exists today, just a handful of houses and a post office and a church.

But in the 1880s, it was the site of one of the largest canel coal operations in the state.

Canel coal burned hotter and cleaner than batuminous coal, and it was prized for gaslighting and domestic heating.

The mines around Canel City extracted thousands of tons of it every year.

And if two men named Puit and Burke had survived the collapse in 1885, there had to be a record of what had happened to the men who did not survive.

Margaret began her search in the newspaper archives, the Lexington Daily Press, the Louisville Courier Journal, the Regional Weeklys that covered the mountain counties.

She was looking for any mention of a mine collapse in Morgan County in 1885.

And at first, she found nothing.

No headlines, no death notices, no accounts of rescue efforts or recovery operations.

It was as if the collapse had never happened.

This was not entirely surprising.

Mine accidents in the 1880s were common enough that they did not always make the papers, especially if the casualties were few.

But the inscription on the photograph suggested something significant.

You did not have your portrait taken to commemorate surviving a minor incident.

You did not write survived the collapse unless the collapse had been serious enough to kill.

So Margaret tried a different approach.

She contacted a colleague at the University of Kucky’s special collections library, a historian named Dr.

Samuel Whitaker, who had spent his career studying labor conditions in Appalachian coal mines.

She sent him scans of the photograph and asked if he had ever encountered anything about a collapse at Canel City.

Dr.

Whitaker’s response came 3 days later.

He had not heard of the collapse, but he had heard of the Canel City Mining Company.

And what he told Margaret changed the direction of her entire investigation.

The Canel City Mining Company, Dr.

Whitaker explained, was owned by a consortium of investors based in Cincinnati.

The principal owner was a man named Horus Fleming, a banker and real estate speculator who had made his fortune in the years after the Civil War by buying up mineral rights throughout eastern Kentucky.

Fleming had never visited his mines personally.

He preferred to manage his investments from a distance through a series of local superintendent who were paid to maximize production and minimize costs.

And one of the costs they minimized most aggressively was the cost of worker safety.

In the 8080s, there was no federal agency that regulated mine safety.

The few state laws that existed were poorly enforced, especially in remote counties where the mining companies effectively controlled the local government.

Inspections were rare, and when they did occur, they were often announced weeks in advance, giving the companies time to make cosmetic improvements before the inspectors arrived.

The men who worked underground had no union, no legal protections, and no recourse if they were injured or killed on the job.

Dr.

Whitaker had one more piece of information.

He had found buried in a box of uncataloged papers from a defunct law firm in Frankfurt, a partial transcript of a state legislative hearing from 1887.

The hearing had been convened to investigate conditions in Kentucky coal mines.

And one of the witnesses who testified was a former foreman from the Canel City operation.

His name was William Stamper.

And according to the transcript, Stamper had described a practice that made Margaret’s blood run cold.

The practice was simple.

When a man died in the mine, his equipment was collected and reassigned to a E2 new worker.

His lamp, his pick, his helmet, everything.

The company kept no record of the transfer.

As far as the official documentation was concerned, the dead man’s equipment had simply continued to be used by the dead man.

His name stayed on the roster.

His number stayed on the lamp.

And when state officials came to count how many men were working underground, they counted the living and the dead together.

Why would a company do this? The answer was in the arithmetic of the era’s mining regulations.

Under Kentucky law, mines that employed more than 10 workers were subject to periodic safety inspections.

Mines that had experienced fatal accidents were subject to additional scrutiny and potential fines.

But a mine where nobody had officially died, where every worker returned home at the end of every shift, where the lamp rack was always full, that mine could operate without interference.

By keeping the names of dead men on the roster by reassigning their equipment to new workers without documentation, the Canel City Mining Company had found a way to make death invisible.

The men in the photograph were not holding their own lamps.

They were holding the lamps of men who had been erased.

Margaret spent the next several weeks trying to find out who those men had been.

She drove to Morgan County and spent days in the county clerk’s office paging through birth and death records from the 1880s.

She visited the Canel City Cemetery, a small plot on a hillside overlooking what had once been the main shaft of the mine.

She talked to local historians, amateur genealogologists, anyone who might have preserved oral histories from the era.

What she found was fragmentaryary but damning.

The death records showed several miners from Canel City who had died in 1884 and 1885, but the causes of death were vague.

Accident injury, sudden illness.

None of them mentioned a collapse.

None of them mentioned the mine by name.

It was as if the county officials had been instructed to keep their descriptions as generic as possible.

But the cemetery told a different story.

Margaret found a row of six graves near the back of the plot, all dated within two weeks of each other in March 1885.

The headstones were simple, just names and dates, no epitaps.

And five of the six names matched death records that listed the causes accident with no further explanation.

Six men had died in March 1885, and there had been no newspaper coverage, no official investigation, no record of what had happened to them.

Margaret contacted Dr.

Whitaker again and asked him to search for any surviving company records from the Canel City operation.

He found nothing in the university archives, but he suggested she try the Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives in Frankfurt, which held records from defunct state agencies, including the old Bureau of Mines.

The Bureau of Mines had been created in 1884, the year before the collapse.

It was Kucky’s first attempt to regulate the mining industry, and it had been underfunded and understaffed from the start.

The bureau’s records were spotty, poorly organized, and difficult to read.

But Margaret found what she was looking for.

There was a letter dated April 1885 from the state mine inspector to the superintendent of the Canel City Mining Company.

The letter referenced an incident that had occurred in March and noted that the inspector had received conflicting reports about the number of workers present at the time.

The inspector requested a complete roster of all employees and a full accounting of all equipment assigned to each worker.

The superintendent’s response was also in the file.

It was brief and dismissive.

The incident, he wrote, had been a minor roof fall that had resulted in no serious injuries.

All workers had been accounted for.

There was no need for further investigation.

The inspector had apparently accepted this explanation.

There was no record of any follow-up, no site visit, no interviews with workers.

The matter had been closed.

But someone had not accepted the company’s version of events.

Someone had preserved the truth in a different form.

And Margaret finally found that truth in the most unexpected place.

The deceased school teacher, whose estate had donated the photograph, had also donated several boxes of family papers.

Margaret had set these aside during her initial sorting, assuming they contained nothing relevant to the photograph.

But now she went back to them.

The school teacher’s name was Eliza Puit.

Her maiden name was Burke, and her great-grandfather had been James Burke, the man on the right side of the photograph.

Among the family papers was a handwritten account dated 1912 written by James Burke himself.

He had composed it late in life decades after leaving the mines as a record for his children and grandchildren.

And in it he described what had happened at Canel City in March 1885.

The collapse had occurred on a Tuesday afternoon.

A section of the main tunnel weakened by months of inadequate timbering had given way without warning.

Burke and his friend Thomas Puit had been working near the mine entrance and had managed to escape, but six men who were deeper in the tunnel had been trapped.

The foreman had organized a rescue effort, but the company superintendent had arrived within an hour and ordered everyone to stop.

The reason, according to Burke, was simple.

A state inspector was scheduled to visit the mine the following week.

If the inspector arrived to find a collapsed tunnel and six dead bodies, there would be an investigation.

There would be fines.

There might even be criminal charges.

The superintendent could not allow that to happen.

So, the collapsed section of the tunnel was sealed off.

The rescue effort was abandoned.

The six men were left where they fell, buried under tons of rock and earth, and their names were kept on the company roster as if they were still alive.

They gave us their lamps, Burke wrote, told us to carry them like they was our own.

Said if anyone asked, we was to say nothing.

Said if we talked, we would never work in coal again.

And a man who cannot work cannot feed his children.

Burke and Puit had kept their silence, but they had also kept the evidence.

They had gone to a photographers’s studio in Lexington, far from Canel City, and they had posed for a portrait.

They had held the lamps with their borrowed numbers facing the camera, and they had written the truth on the back of the photograph, hoping that someday someone would understand.

“We wanted them to be remembered,” Burke wrote.

The company took their names off the books, but we put them back on in the only way we knew how.

Margaret brought her findings to the museum’s director, a man named Richard Hensley, who had held the position for 12 years.

She showed him the photograph, the family papers, the state records, the testimony from the 1887 hearing.

She explained what the lamp numbers meant, and why this image was not just another portrait of anonymous coal miners.

It was evidence.

It was a witness statement captured in silver and light.

It was proof of a coverup that had lasted more than a century.

Hensley listened carefully.

He asked thoughtful questions and then he told Margaret that he needed to consult with the museum’s board before making any decisions about how to proceed.

The board meeting took place 2 weeks later.

Margaret was invited to present her research.

She prepared carefully, printing copies of all the documents, creating a timeline of events, rehearsing her explanation of why this photograph mattered.

She expected skepticism.

She did not expect what actually happened.

The board was composed of 12 members, most of them business leaders and philanthropists from the Lexington area.

Several of them had connections to the coal industry.

One of them, a retired executive named Walter Fleming, was a direct descendant of Horus Fleming, the original owner of the Canel City Mining Company.

Walter Fleming did not raise his voice.

He did not accuse Margaret of anything.

He simply asked in a tone of polite concern whether the museum was certain that its interpretation of the photograph was correct, whether there might be other explanations for the mismatched lamp numbers, whether it was really appropriate for a regional history museum to make accusations against families who had contributed so much to the development of the state.

Other board members echoed his concerns.

They worried about the museum’s reputation.

They worried about the reaction from donors.

They worried about the politics of it all, the way some people might use this story to attack the coal industry at a time when the industry was already struggling.

One member suggested that the photograph should simply be added to the collection without any special interpretation, just another image of Kentucky coal miners from the 19th century.

Margaret felt the familiar weight of a story being pushed back underground, but she also had allies.

Dr.

Whitaker had agreed to attend the meeting as an outside expert and he spoke forcefully about the historical significance of the photograph.

A younger board member, a woman named Patricia Chen, who ran a nonprofit focused on Appalachian heritage, argued that the museum had an obligation to tell difficult truths, not just comfortable ones.

And in the end, a compromise was reached.

The museum would mount a small exhibition featuring the photograph in Margaret’s research.

The exhibition would be framed not as an accusation against any specific family or company, but as an exploration of labor conditions in 19th century coal mines and the ways that workers found to preserve their own histories.

The Fleming family would not be named directly.

The focus would be on the system, not the individuals who profited from it.

It was not everything Margaret had hoped for, but it was something.

The exhibition opened 6 months later.

It occupied a single room on the museum’s second floor, and it attracted more attention than anyone had expected.

A journalist from Louisville wrote a long feature about it.

A documentary filmmaker began developing a project on 19th century mine safety, and descendants of the six men who had died in the Canel City collapse began to come forward.

Margaret had managed to identify five of the six through Burke’s account and the cemetery records.

Their names were William Sloan, Patrick [clears throat] Hennessy, Thomas Cold Iron, Henry Maize, and a man known only as old German John, whose surname had been lost.

The sixth man remained unknown.

But the families of the five knew their stories passed down through generations, and they came to the museum to see the photograph that had finally brought those stories into the light.

One of them was a woman named Diane Cold Iron, the great great granddaughter of Thomas Cold Iron.

She had grown up hearing about her ancestor who had died in the mines.

But the family had always believed it was a simple accident, a tragic but ordinary hazard of the work.

They had never known about the cover up.

They had never known that his body had been left underground, deliberately abandoned to protect a company’s reputation.

Diane stood in front of the photograph for a long time.

She looked at the two men holding their borrowed lamps and she thought about her ancestor trapped in the darkness while the world above went on as if nothing had happened.

And then she said something that Margaret would never forget.

They thought they could erase him.

They thought they could make him disappear.

But they could not because these two men, these two survivors, they refused to let him be forgotten.

They carried his lamp.

They carried his memory.

And now 130 years later, here we are still remembering.

The exhibition closed after 3 months, but its effects continued.

The Kentucky Historical Society added a page to its website about the Canel City collapse.

Drawing on Margaret’s research, the state legislature passed a resolution honoring the six miners who had died, belatedly acknowledging what the state had failed to acknowledge in 1885.

and the museum received a donation from an anonymous source enough to fund a larger permanent exhibition on the history of coal mining labor in Appalachia.

Margaret does not know who made the donation.

She suspects it might have been Walter Fleming trying to make amends for sins his family never publicly confessed.

Or it might have been someone else entirely, someone moved by the story of two men who had risked their livelihoods to preserve the truth in the only way they could.

It does not really matter.

What matters is that the story is finally being told.

Photographs lie.

This is something that historians and archavists understand, but that most people prefer not to think about.

We look at old images and we assume that what we see is what was there, a happy family, a prosperous farm, a proud worker.

We do not ask what was just outside the frame.

We do not ask what the photographer was paid to hide.

But sometimes, if you look closely enough, the truth finds its way into the image anyway.

A reflection in a window, a shadow that should not be there, a detail so small that the person who staged the photograph never noticed it, a lamp number that does not match.

Across the archives of America, in museums and historical societies and family attics, there are thousands of photographs like this one.

images that look ordinary on the surface but contain, buried in their details.

Evidence of crimes that were never prosecuted.

Deaths that were never acknowledged, lives that were erased to protect the powerful and the profitable.

The Canel City collapse was not unique.

It was typical.

In the decades after the Civil War, as the coal industry expanded across Appalachia, thousands of men died underground in accidents that were never properly documented.

never properly investigated, never properly remembered.

The companies that employed them had every incentive to minimize the death toll and every means to do so.

The workers who survived had every reason to stay silent and almost no power to speak out.

But some of them found ways.

They carved initials into beams that would later be discovered by demolition crews.

They whispered stories to their children that would be passed down for generations.

They posed for photographs with borrowed equipment, trusting that someday someone would look closely enough to see what they were trying to say.

Thomas Puit and James Burke could not bring their six friends back to life.

They could not force the company to admit what it had done.

They could not even speak openly about what they had witnessed without risking their ability to feed their families.

But they could stand in front of a camera holding the lamps of dead men and let the evidence speak for itself.

It took 130 years, but someone finally listened.

The next time you see an old photograph, whether it is in a museum or a textbook or your own family’s collection, look closely.

Look at the edges in the shadows and the small details that seem unimportant.

Ask yourself what the image is not showing you.

Ask yourself what someone might have been trying to hide.

Because the dead cannot speak for themselves.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

This 1868 Portrait of a Teacher and Girl Looks Proud Until You See The Bookplate

This 1858 studio portrait looks elegant until you notice the shadow. It arrived at the Louisiana Historical Collection in a…

End of content

No more pages to load