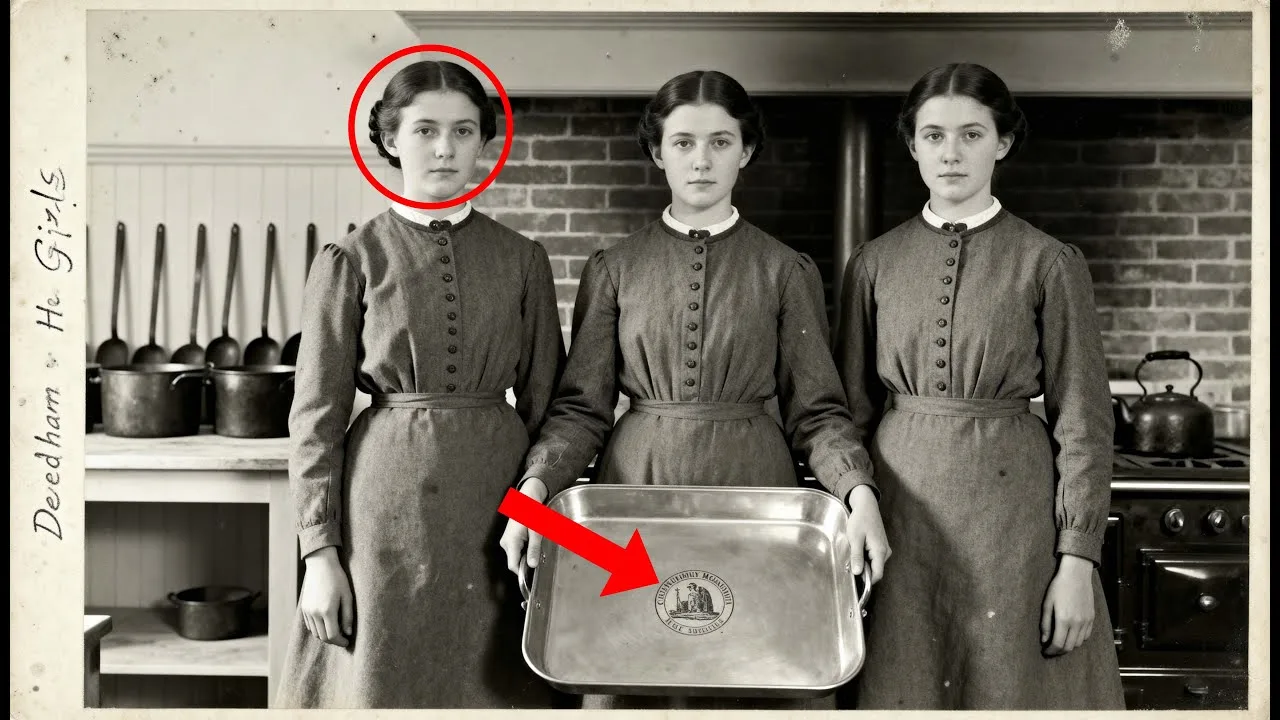

This 1881 portrait of three boarding house women seems normal until you notice the stamp on the tray.

At first glance, it looked like a promotional image.

Three women in matching aprons, hair pinned back, standing beside a long serving tray in what appeared to be a commercial kitchen.

The kind of photo any respectable establishment might commission to advertise its clean, orderly staff.

But there was something about the tray, a mark that did not belong.

Naomi Ashford had been cataloging photographs for the Massachusetts Historical Society for almost 11 years.

She had seen thousands of images from the 19th century, studio portraits of merchants and their families, tin types of Civil War soldiers, cabinet cards documenting the rise of Boston’s industries.

Most of them told predictable stories, ones that fit neatly into the city’s narrative of progress and prosperity.

This one did not.

The photograph had arrived as part of a larger donation, the contents of an attic in a Beacon Hill townhouse whose last owner had died without direct heirs.

The collection was mostly unremarkable.

Receipts from dry good stores, a bundle of letters written during the Spanishame War, a Bible with generations of names inscribed in fading ink.

And at the bottom of the third box, wrapped in tissue paper that had yellowed to the color of old teeth, a single album in print mounted on cardboard.

Naomi almost passed over it.

The image quality was decent, but not exceptional.

The composition was stiff.

The women stared straight ahead with the flat practiced expressions common to long exposures.

It was only when she placed the print under her magnifying lamp to check for damage that she noticed the detail that would consume the next 8 months of her life.

The serving tray the women held between them was embossed, not with a hotel name or a business logo, which would have been typical for a promotional photograph.

Instead, the faint outline of a seal was pressed into the metal.

A seal Naomi recognized immediately.

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

She leaned closer, adjusting the angle of the light.

The seal was unmistakable.

The shield with its Native American figure, the arm holding a sword above, the motto curving beneath.

This was official state property.

But why would a boarding house kitchen use stateisssued equipment? Why would three women in domestic aprons pose with a tray that belonged to the government? Naomi turned the photograph over.

On the back, in pencil so faint it was almost invisible, someone had written three words, denim house girls.

She set the print down carefully.

In more than a decade of handling historical materials, she had developed an instinct for when something was wrong.

Not damaged or misfiled, but wrong in a deeper sense.

When an image contained a story that did not want to be told, this photograph, with its ordinary surface and its strange details, was setting off every alarm she had.

She pulled out her notebook and began, and to write.

Naomi had come to archival work through an unusual path.

She had started as a social worker in the early 2000s, spending 5 years in the foster care system before burnout drove her to graduate school.

Her dissertation had focused on 19th century charity organizations in New England, the institutional ancestors of the systems she had once navigated from the inside.

She understood in a way that purely academic researchers sometimes did not, how bureaucracies could absorb people, how they could reshape lives while leaving almost no record of the individuals who passed through them.

That background made her meticulous.

When she removed the photograph from its protective sleeve, she did so with cotton gloves and a pair of plastic tweezers.

She examined the cardboard mount for printers marks or studio stamps.

She measured the dimensions and noted the slight foxing along the upper left edge.

She photographed both sides at high resolution before beginning any research.

The back of the mount yielded a few more clues.

Below the pencileled inscription, almost invisible without magnification, was a small printed label.

Warren and Comr.

Commercial photography, 114 Tmont Street, Boston.

A reputable studio, one she had encountered before.

They had specialized in business portraits and institutional documentation.

That last category caught her attention, institutional documentation.

She also noticed, pressed into the lower right corner of the cardboard, a tiny number, 7 to 23, a filing reference perhaps, or a sequence number from a larger set, which meant there might be more photographs, more women, more trays with state seals.

She placed the print back in its sleeve and opened her laptop.

The first search was simple.

Denim House, Boston, 1880s.

The results were sparse.

A few mentions in genealological databases, a footnote in a history of Massachusetts corrections.

Nothing substantial, but the word corrections sent her in a new direction.

She refined her search.

Dedum House of Industry, State Reformatory for Women, Massachusetts.

Female inmates, domestic service, 1880s.

The fragments began to accumulate.

references to a network of institutions that had operated across the state in the decades after the Civil War.

Houses of correction, industrial schools, reformatories for the morally weward facilities that existed somewhere between prison and charity where women convicted of minor crimes or sometimes no crimes at all could be held indefinitely for the purpose of moral rehabilitation.

Naomi had known these institutions existed.

She had encountered them in her dissertation research, though they had been peripheral to her main argument.

What she had not known, what the photograph was now forcing her to confront, was that the rehabilitation often took a very specific form.

The women were put to work, not in thereries or sewing rooms that most histories described.

According to a passing reference in an 1879 report from the state, board of charities select inmates from certain facilities were placed out in private homes and businesses.

They worked as domestic servants, cooks, and cleaning staff.

Their wages, if they received any, went to the state, and if they ran, they could be arrested and returned to serve additional time.

The photograph took on a different meaning.

The matching aprons, the formal pose, the flat expressions.

These women were not employees.

They were inmates.

The boarding house kitchen was their assignment, and the state seal on the tray was the mark of their bondage.

But Naomi needed more than a theory.

She needed names.

The Warren and Corb studio had closed in 1912, but their records had survived.

A bulk purchase by a private collector in the 1940s had eventually made its way to the Boston ANAM where a partial client list and appointment book were available on microfilm.

Naomi spent two days scrolling through blurred handwriting.

The studio had been prolific, serving hundreds of clients per year.

Most entries were brief, a name, a date, a description of the order.

Mr.

and Mrs.

Eaton, cabinet card, two copies.

First Congregational Church, group portrait, 12 copies.

Weston manufacturing factory floor six plates on the third roll of microfilm she found it July 23rd 1881 denim house domestic series four plates per matron Collins state account four plates four photographs Naomi had only one filing number on the back suddenly made sense 723 was not an arbitrary reference it was the date of the sitting rendered in shorthand July 23rd but where were the other three photographs and who was matron Collins.

The state archives of Massachusetts occupied a brutalist building in Dorchester, a monument to 1970s institutional architecture that Naomi had visited many times.

The staff knew her by name.

When she submitted her request for records related to the Denim House of Industry, the chief archavist, a soft-spoken man named Gerald Hang, raised an eyebrow.

“That’s a collection we don’t get many requests for,” he said.

Most of it’s still in the original filing system.

Boxes and boxes of intake forms, board of directors minutes, that kind of thing.

Are you looking for something specific? Naomi showed him a print out of the photograph.

Gerald studied it for a long moment.

The tray, he said quietly.

You noticed.

I’ve worked here for 31 years.

I know what our seal looks like.

He handed the print out back.

Give me a couple of hours.

I’ll see what we have.

What they had was 16 boxes spanning 1865 to 1893.

Intake registers, inmate files, many of them incomplete, correspondence with the state board of charities, financial reports, and in the 14th box bound with a deteriorating ribbon, a folder labeled placement program, 1878, 1886.

Naomi put on fresh gloves and began to read.

The placement program had been established as a reform measure.

According to the introductory memo, the stated purpose was to provide inmates with practical training and domestic economy while offsetting the costs of their incarceration.

Private households and businesses could request workers from the state.

The inmates would serve for a contracted period, typically 6 months to 2 years.

Their conduct would be monitored by the matron who could recall them at any time for infractions.

The language was clinical, bureaucratic.

It could have described a job training initiative if not for the details buried in the margins.

Inmates who refused placements were subject to solitary confinement.

Those who ran away faced additional years of detention.

Payments from employers went directly to the institution, not to the women themselves.

And the criteria for initial commitment were shockingly broad.

vagrancy, lewd and lascivious conduct, stubbornness being found in the company of disreputable persons.

In practice, the documents revealed almost any poor woman could be swept into the system.

A landlord’s complaint, a neighbor’s accusation, a police officer’s judgment that she was idle or disorderly.

Once committed, she could be held for years, her labor extracted and sold to whoever was willing to pay.

Naomi flipped through the placement records looking for the boarding house.

She found it on page 47 of the 1881 ledger.

Mrs.

Karen Fitch, 22, Charter Street boarding house, requests three domestics for kitchen and cleaning duties.

Contract term one year, payment 250 per week per inmate to the house, $2.50 per week.

In 1881, a free domestic servant in Boston earned between $3 and $5 per week plus room and board.

Mrs.

Fitch was getting a discount and the women were getting nothing.

The ledger listed the names of the inmates assigned to the Charter Street boarding house.

Ellen Doyle, age 19, committed for vagrancy.

Mary Alice Coran, age 24, committed for night walking.

Bridget Sullivan, age 17, committed for stubbornness at the request of her stepfather.

Bridget was 17.

In the photograph, the youngest looking woman stood on the right, her hands gripping the edge of the tray so tightly that her knuckles were white.

Gerald found Naomi an hour later still reading.

She had moved on to the individual inmate files, what remained of them.

Ellen Doyle’s file was thin, a single intake form, a brief physical description, a note that she had been placed out multiple times.

Mary Alice Corrian’s file was thicker, documenting two escape attempts in the additional years added to her sentence as punishment.

But it was Bridget Sullivan’s file that stopped Naomi cold.

Bridget had been committed in March of 1880 at the age of 16.

Her intake form listed her offense as stubbornness and refusal to obey lawful commands.

The complainant was her stepfather, a man named Thomas Keller.

According to the form, Bridget had repeatedly defied household authority and associated with low companions.

The committing magistrate had sentenced her to the Denim House until the age of 21, a term of 5 years.

But tucked into the back of the file was a letter handwritten dated November 1880 addressed to the matron.

The return address was the Boston Female Moral Reform Society.

Dear Matron Collins, the letter began.

We have received credible reports that the girl Bridget Sullivan was committed to your institution under false pretenses.

Multiple witnesses have stated that Mr.

Keller sought her commitment not because of any moral failing on her part, but because she resisted his improper advances.

We urge you to investigate this matter and if the reports are confirmed to arrange for her release into the care of our society.

The letter was signed by a Mrs.

Henrietta Blackwood corresponding secretary.

There was no record of any investigation, no indication that the matron had responded.

6 months after this letter was written, Bridget Sullivan was standing in a boarding house kitchen holding a tray stamped with the seal of the state that had imprisoned her.

Naomi read the letter three times.

Then she closed the folder and sat in the silence of the archive reading room, trying to process what she had found.

A girl had reported abuse.

She had been punished for it.

The system that claimed to protect women’s morals had been used by her abuser to silence her.

And then that same system had sold her labor to a private business while keeping every penny for itself.

This was not an anomaly.

This was not a single corrupt official or a clerical error.

The documents made clear that the placement program was systematic.

Hundreds of women had passed through it.

They had worked in homes, in hotels, inies, and factories across the state.

Their wages had funded the very institution that held them captive, and no one remembered.

Naomi requested copies of everything.

Then she called the one person she knew who might understand what she was looking at.

Dr.

Lorraine Jeffers was a professor of history at Boston College, specializing in gender and incarceration in the 19th century.

Naomi had met her at a conference years earlier and had stayed in occasional contact since.

When Naomi explained what she had found, Lorraine was quiet for a long moment.

“You’re describing a convict leasing system,” she said finally.

“We usually associate that with the South.

Chain gangs, tarpentine camps, that kind of thing.

But there were versions of it everywhere.

They just looked different.” These women weren’t on chain gangs.

They were in kitchens.

Exactly.

The labor was gendered.

The exploitation was the same.

They called it moral reform, but it was forced labor.

And because the inmates were women and often poor or immigrant women, nobody called it what it was.

Lorraine agreed to review the documents.

A week later, she called back with additional context.

The Dham House of Industry had been one of at least six similar institutions in Massachusetts during the 1880s.

The placement programs had varied in structure, but the basic model was consistent.

Women were committed on vague charges held indefinitely and put to work for private employers.

The practice had declined in the 1890s, partly due to labor movement pressure, and partly due to a series of scandals that the state had worked hard to suppress.

There were investigations, Lorraine said.

I found references to at least two legislative inquiries, but the reports were never published.

The committees concluded that the institutions were performing valuable service and recommended only minor reforms.

What happened to the women? Some were released when their terms ended.

Some died in custody.

Some ran and were never caught.

A few ended up in asylums.

The records are scattered.

Most of the individual files were destroyed in a warehouse fire in 1924.

Convenient.

Very.

Naomi returned to the photograph.

She had highresolution scans now, and she studied them obsessively.

The women’s faces, their posture, the details of the kitchen behind them, and always the tray, the seal that should not have been there.

She began to notice other things.

The aprons the women wore were unusually heavy, more like smoks than the standard domestic uniform.

They buttoned at the back, which would have made them difficult to remove without assistance.

The sleeves were long, extending past the wrists, and the cuffs appeared to be reinforced with a stiffer material.

Not quite restraints, but close in the women’s hands.

Naomi had initially focused on Bridget Sullivan’s white knuckled grip on the tray, but now she looked more closely at the other two.

Ellen Doyle’s hands were visible only as shadows against the apron fabric, but Mary Alice Corrian’s right hand, partially hidden behind the tray, appeared to be making a gesture.

Two fingers extended, the others curled.

Naomi searched for similar gestures in other photographs from the period.

She found nothing conclusive, but a footnote in Lraine’s dissertation mentioned that inmates in some reformatories had developed subtle signals to communicate with each other without attracting the notice of their keepers.

a way of saying, “I see you.

I know what this is.

I am still here.” Was Mary Alice signaling to someone, to the photographer, to a future viewer who might decades later notice what she was trying to say? It was speculation.

Naomi reminded herself of that, but the speculation led her to ask a different question.

Not just what was done to these women, but how they responded.

whether there were traces of resistance in the archive, whether anyone had fought back.

The Boston Female Moral Reform Society, the organization that had written to Matron Collins on Bridget’s behalf, had left substantial records.

Their papers were held at the Schlesinger Library at Harvard, and Naomi spent a week working through them.

The society had been founded in 1839 as part of the broader antibbellum reform movement.

Their original mission had focused on rescuing women from prostitution and preventing the ruin of the young.

But by the 1870s and 1880s, a faction within the organization had begun to take a more critical stance toward the state institutions that claimed to serve the same goals.

They argued that many of the women in reformatories were not criminals at all, but victims of poverty, male violence, and a legal system that punished women for conditions beyond their control.

Henrietta Blackwood, the woman who had written about Bridget Sullivan, was a leader of this faction.

Her correspondence revealed a sustained campaign to expose abuses in the placement program.

She had gathered testimony from former inmates.

She had lobbyed state legislators.

She had published articles in reform journals under a pseudonym and she had been systematically ignored.

Her letters grew increasingly frustrated over the years.

In 1882, she wrote to a fellow reformer.

I have placed evidence before the board three times now.

Each time they assure me that the matter will be looked into.

Each time nothing changes.

The institutions have powerful friends.

They provide cheap labor to businesses whose owners sit on charitable boards and donate to political campaigns.

We are fighting a system that profits from its own cruelty.

In 1884, Henrietta Blackwood died of tuberculosis at the age of 53.

Her papers were boxed and forgotten until they were donated to the Schlesinger 50 years later.

The placement program continued until 1891 when it was quietly discontinued with no public explanation.

Naomi could not find any record of what happened to Bridget Sullivan after the photograph was taken.

Her file at the state archives ended with the 1881 placement.

No release date, no death record, no transfer to another institution.

She simply vanished from the documentary record.

A gap that could mean escape, death, or deliberate erasure.

But Ellen Doyle appeared again.

In 1889, a woman named Ellen Doyle gave testimony to a private investigator hired by a reform organization.

The transcript, barely legible, was tucked into the society’s correspondence files.

Ellen described her years at the Denim House in plain, devastating language.

They called it training, but it was servitude.

We worked from 5 in the morning until 9 at night.

We were not paid.

We could not leave.

If we complained, we were punished.

If we ran, we were caught and brought back and given more years.

I saw girls beaten for breaking dishes.

I saw girls locked in closets for speaking to men who came to deliver supplies.

We were told it was for our own good, that we were learning to be respectable.

But we knew, we all knew, we were prisoners and our labor was being sold.

Ellen had been released in 1886 after serving 6 years.

She had found work as a laress and had eventually married.

The investigator asked her if she would testify publicly.

She refused.

“They would find a way to send me back,” she said.

“They always do.” In the spring, Naomi brought her findings to the director of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

“Dr.

Patricia Webb was a cautious administrator, conscious of the society’s relationships with donors and board members.

She listened to Naomi’s presentation with an expression that shifted gradually from interest to concern.

“This is remarkable research,” Dr.

Web said when Naomi finished.

“But I’m not sure how we should present it.” “What do you mean?” “The photograph came from the Peton estate.

The Petanss have been donors to this institution for generations.

If we exhibit this image with the interpretation you’re proposing, we’re essentially accusing their ancestors of participating in a system of forced labor.

The evidence is clear.

The boarding house at 22 Charter Street was owned by a family connected to the Petanss by marriage.

They used inmate labor.

The documents prove it.

Documents can be interpreted in different ways.

How else would you interpret a contract that pays the state for the work of women who are legally imprisoned? Dr.

Webb sighed.

I’m not disagreeing with your conclusions.

I’m pointing out that there will be push back.

board members who don’t want to deal with the controversy, descendants who will threaten legal action, other institutions that benefited from similar programs and don’t want the precedent of exposure.

Naomi thought of Henrietta Blackwood writing letter after letter to officials who assured her the matter would be looked into.

She thought of Ellen Doyle, afraid to testify because they would find a way to send me back.

The women in this photograph were silenced for their entire lives, Naomi said.

Bridget Sullivan was imprisoned as a teenager for resisting her stepfather’s abuse.

Mary Alice Coran had years added to her sentence for trying to escape.

Ellen Doyle spent 6 years in forced labor and was too afraid to speak about it for the rest of her life.

If we have evidence of what was done to them and we choose not to present it because it might upset donors, then we are participating in the same system of silence that enabled the abuse in the first place.

Dr.

Webb was quiet for a long moment.

Then she nodded slowly.

Write up a full proposal, include everything, the photograph, the documents, the historical context.

I’ll take it to the board myself.

The board meeting was contentious.

Several members expressed concern about politicizing the society’s collections.

One suggested that the photograph could be exhibited without the inflammatory interpretation simply as an example of 19th century commercial photography.

Another warned that the Peton family might withdraw their ongoing support.

But the society’s chief archavist, Gerald Hang, spoke in favor of the exhibition.

So did two academic board members who had reviewed Naomi’s research and found it unimpeachable.

In the end, the board voted six to four to proceed with a small exhibition built around the photograph and its story.

The exhibition opened the following October.

It occupied a single room on the third floor, modest in scale but carefully designed.

The photograph hung at the center, enlarged and accompanied by detailed annotations identifying each woman and explaining the significance of the state seal on the tray.

Surrounding panels presented the documentary evidence.

the placement contracts, the intake records, Henrietta Blackwood’s letter about Bridget Sullivan, Ellen Doyle’s testimony from 1889.

A final panel addressed the broader system.

Maps showed the locations of similar institutions across Massachusetts.

Charts documented the flow of money from private employers to the state.

Excerpts from legislative debates revealed how critics had been dismissed and investigations had been suppressed.

The last image in the exhibition was not a photograph, but a list.

Names of women who had been placed out from the Denim House between 1878 and 1886 recovered from the archival records.

347 names, some with additional information, ages, offenses, placement locations, most with nothing but a name and a date of commitment.

Visitors to the exhibition often stood in front of that list for a long time.

Some took photographs of individual names.

A few Naomi learned later were descendants of women on the list, tracing family histories that had been deliberately obscured for generations.

The publicity brought new sources to light.

A family in Worcester donated a bundle of letters written by a woman who had been held at a similar institution in the 1870s.

A retired professor shared research she had conducted decades earlier on placement programs in New Hampshire and Connecticut.

A graduate student at UMass began a dissertation on the economic networks that had profited from inmate labor across New England.

And from a small town in Maine, a woman named Catherine Brennan wrote to the society with a story she had been told by her grandmother.

Her grandmother’s mother, she said, had been a girl named Bridget who had come to Maine in 1885 with a new name and a refusal to speak about her past.

She had married, raised children, and lived into her ages.

She had never told anyone where she came from, but on her deathbed, she had given her daughter a single instruction.

If anyone ever asks about me, tell them I survived.

Naomi could not verify the connection.

The name was common.

The dates were plausible, but not conclusive.

But Catherine Brennan had brought something else with her when she visited the exhibition.

A small tin button tarnished with age embossed with a letter D.

Bridget had kept it, her granddaughter said.

She had kept it for her whole life, hidden in a box with her important papers.

No one knew what it meant.

Naomi knew.

D for denim.

A button from the institution that had held her captive, kept not as a momento, but as evidence, as proof that what had happened to her was real, even if no one would ever believe her.

The photograph still hangs in the Massachusetts Historical Society’s permanent collection.

It has been reproduced in several books and articles about 19th century labor exploitation.

Visitors who see it often remark on how ordinary it looks.

Three women in a kitchen, an unremarkable scene from another era.

But the seal on the tray tells a different story.

It says that what looks like ordinary labor can be forced labor.

That what looks like a respectable establishment can be a sight of exploitation.

that the women who appear to be employees can be prisoners whose voices have been systematically erased.

Across the country, in archives and atticts and antique shops, thousands of similar photographs wait to be re-examined.

Portraits of domestic servants who may have been inmates, images of factory workers who may have been convicts, pictures of children and institutions whose care was indistinguishable from imprisonment.

each one a potential doorway into a hidden system, a buried story, an injustice that official history preferred to forget.

The camera does not lie, people sometimes say.

But the camera also does not tell the whole truth.

It shows what the photographer chooses to show.

It preserves what the powerful want preserved.

And sometimes in a reflection or a shadow or a stamp on a tray, it accidentally preserves something else.

A trace of the violence that made the image possible.

A glimpse of the people who were supposed to remain invisible.

Bridget Sullivan was 17 years old when she stood in that kitchen.

She had been imprisoned for refusing to submit to her stepfather’s abuse.

She had been sold as a laborer to a business that paid the state for her work.

She had been photographed as evidence of that business’s respectable workforce.

And then she had vanished from the record, surviving only as a faint figure in an image that almost no one bothered to examine closely.

But she had survived.

Somewhere in Maine, under a different name, she had built a life that the system had tried to deny her.

She had kept a button as proof.

And a century later, her story was finally being told.

Not because the system wanted it told, but because someone noticed a seal on a tray and refused to look

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load