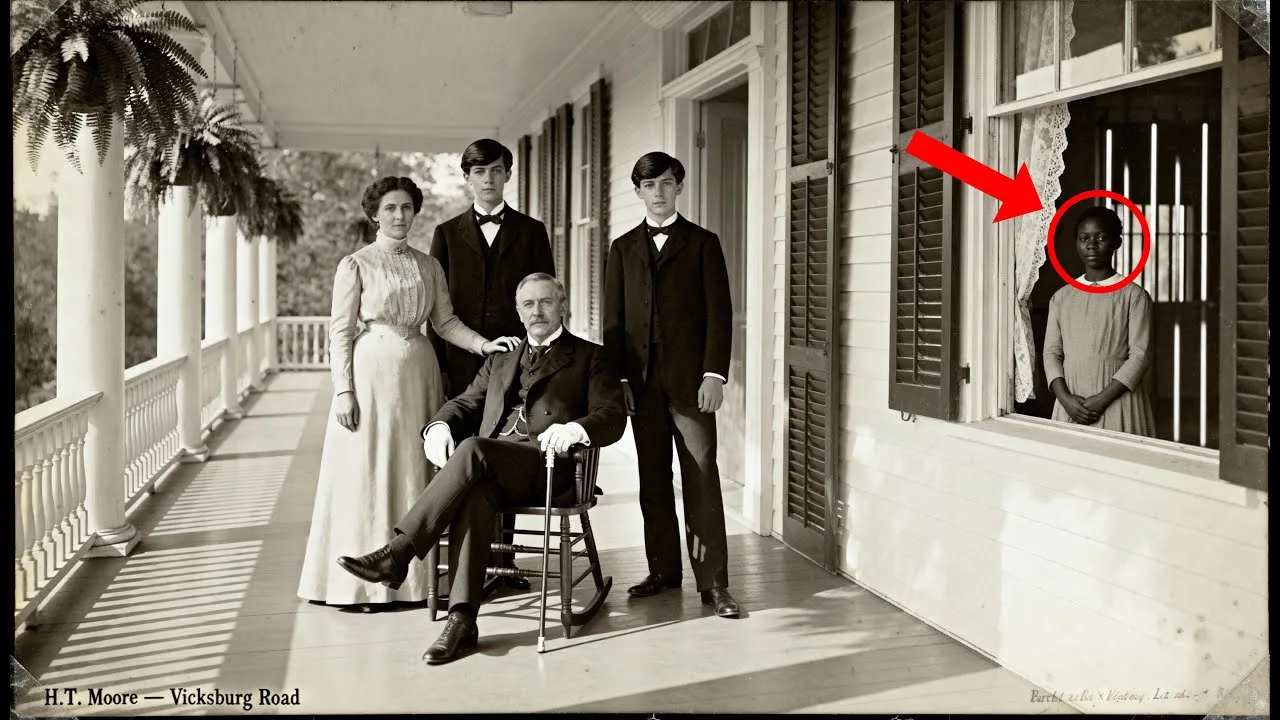

This 1876 plantation photo looks idyllic muntil you notice the window.

At first

glance, it is exactly what you would

expect from a prosperous southern family

portrait.

The clothing is formal.

The

expressions are composed.

The porch is

wide and handsome.

But when you look

closer at the young black girl visible

through the glass behind them, something

refuses to make sense.

Dr.

Amelia

Chambers found the photograph in a

banker’s box at the back of a climate

controlled vault in Jackson,

Mississippi.

She had been consulting for

the Mississippi Heritage Center for 6

months, cataloging their collection of

post civil war domestic photography.

Most of what she handled followed

predictable patterns.

Stiff poses, bad

lighting, fading sepia tones that made

everyone look equally dead.

This one sat

in a manila folder marked only Collier

Estate 1876.

She almost put it in the general

plantation category without a second

thought.

The image shows five people on

a columned ver.

The father sits in the

center, legs crossed, one hand resting

on a silver topped cane.

His wife stands

to his left, her hand placed lightly on

his shoulder.

Two teenage boys flank

them, straightbacked, hair oiled flat.

The house behind them is pale and clean,

framed by hanging ferns.

To the far

right, through an open window with lace

curtains tied back, a young black girl

stands with her hands folded in front of

her.

She looks maybe 12 or 13.

Her dress

is plain but neat.

Her posture is

perfect.

Chambers lifted the photo under

her desk lamp and adjusted the

magnification lens she kept mounted on a

flexible arm.

She had done this

thousands of times.

Check the edges for

damage.

Look for retouching.

Note any

handwritten labels.

She moved the lens

slowly across the image, left to right.

Then she stopped at the window.

The

glass pane caught light from the

photographers’s flash powder.

Most of

the reflection showed the trees and sky

opposite the house, but along the

interior edge, just visible where the

girl stood, chambers could see faint

vertical lines.

She increased the

magnification.

The lines were evenly

spaced, cast shadows inward.

She reached

for a jeweler’s loop and bent closer

until her nose nearly touched the print.

iron bars.

Not on the outside of the

window, on the inside.

The room where

the girl stood was locked from the

outside with bars installed to keep

someone in.

Chambers sat back in her

chair.

She had been working in archival

photography for 17 years.

She

specialized in images of enslaved people

and the post-emancipation south.

She had

seen shackles, branding scars, and

auction house backdrops.

She thought she

understood the visual language of

bondage.

But this was different.

This

photograph was taken 11 years after the

13th amendment.

The Collier family had

posed for a formal portrait meant to

project respectability and continuity,

and they had done it with the imprisoned

child visible in the background, either

unaware the bars would show in the

reflection were so confident in their

world that they simply did not care.

She

turned the photograph over on the back

in faded pencil.

family and housegirl,

HT Moore, photographer, Vixsburg Road.

This was not just a pretty old photo.

Something here was wrong.

Chambers had

come to Mississippi from Chicago where

she taught visual culture and American

studies at a small liberal arts college.

She had published two books on how

photographs shaped memory of the Civil

War and Reconstruction.

She knew how to

read images for what they tried to hide.

Most of her career had been spent

looking at portraits that staged power.

Portraits where enslaved people were

placed like furniture to signal wealth.

But those were from before 1865.

After emancipation, the visual

vocabulary was supposed to change.

Servants were supposed to be employees.

Relationships were supposed to be

contractual, not owned.

Except here in

1876, someone had built or maintained a

locked barred room for a black child who

appeared in a family portrait as

casually as a house plant.

Chambers made a highresolution scan of

the photograph.

She adjusted the

contrast and brightness on her monitor

until the reflection in the window

became unmistakable.

She cropped the section showing the bars

and saved it in a separate file.

Then

she photographed the back of the print

with her phone, capturing the pencled

inscription.

She needed more context

before she took this to anyone else.

She

needed to know who these people were and

whether what she was seeing had any

documentation beyond this single image.

She started by searching for HT Moore.

Photographers in the 1870s often

advertised in newspapers and city

directories.

If Moore had a studio on

the Vixsburg Road, there would be a

paper trail.

She pulled up the digitized

archive of the Vixsburg Daily Herald and

searched every issue from 1875 to 1877.

On October 12th, 1876, she found a small

advertisement in the back pages.

HT

Moore photographer portraiture and

estate documentation, Vixsburg Road, 2

mi south of city limits.

Estate

documentation.

That phrase stuck with

her.

It suggested Moore did more than

family portraits.

He likely photographed

property for legal and insurance

purposes.

In the 1870s, that still

sometimes meant photographing people

considered property under old systems

that refused to die.

Next, she looked

for the Collier family.

Mississippi had

decent census records, and the 1870

census included formerly enslaved people

by name for the first time.

She found a

Samuel Collier, a 47, listed as a

planter in Warren County.

wife Mary, age

43, sons Thomas and William, ages 16 and

14.

The household also listed four black

residents.

Rose Collier, 38, laborer.

James Collier, 19, laborer.

Ida Collier,

13, domestic servant.

Peter Collier,

nine, laborer.

Chambers stared at the

screen.

Ida Collier, 13, domestic

servant.

The age matched.

The role

matched.

But why did she still carry the

Collier surname 6 years after

emancipation?

Some freed people kept the names of

former enslavers out of necessity or

lack of alternatives.

Others did so

under pressure or because they had no

legal record of any other identity.

But

still living in the household listed as

a servant in a locked room, she reached

out to Dr.

Leon Harris, a historian at

Tugaloo College, who had written

extensively on debt page and convict

leasing in Mississippi.

She sent him the

scanned image and a brief summary of

what she had found so far.

He called her

back within 2 hours.

Do you know what you are looking at? His

voice was low and careful, the tone of

someone who has seen terrible things in

archives and knows how to handle them.

I

think so, Chambers said.

But I want to

make sure I’m not overreading it.

You

are not, Harris said.

This is textbook

post-emancipation reinsslavement.

The

bars are the giveaway.

We have

documentation of planters across the

Delta who kept black workers in locked

quarters under the pretense of

protecting them or managing labor

contracts.

But what it really was was

imprisonment.

If you ran, the sheriff

brought you back under vagrancy

statutes.

If you complained, you were

charged with insubordination or breach

of contract.

The system was designed to

make freedom uninforcable.

Chambers asked if he could look through

local court records for anything

involving the Collier family.

Harris

agreed.

3 days later, he sent her a

scanned page from the Warren County

Circuit Court docket dated March 1875.

It listed a case state v IDA a minor

Collier household.

The charge was

attempted escape.

The resolution was a

return to the Collier property under a

renewed 12-month labor contract with

wages to be held by Samuel Collier as

guardian until Ida reached majority age.

Ida had been 13 at the time of that

court case.

She would have turned 14 a

few months later around the time the

photograph was taken.

The official

narrative, thin as it was, now had an

outline.

The Collier family had likely

held Ida and the others in some form of

bondage since before emancipation.

After 1865, they restructured the

relationship using labor contracts and

guardianship laws.

When Ida tried to

leave in 1875, the courts sent her back.

A year later, the family commissioned a

formal portrait.

And in that portrait,

Ida appeared behind bars.

What Chambers

still did not understand was why? Why

take a photograph that could document a

crime? Why make visible what so many

other planters worked to hide? She

decided she needed to see the place

itself.

The Collier estate no longer

existed as a working plantation.

Harris

sent her directions to what remained.

It

was 20 minutes south of Vixsburg down a

county road that turned to gravel after

the first few miles.

Chambers drove out

on a cool morning in early November.

The

land was flat and open, planted in

soybeans now instead of cotton.

The

original house had burned in the 1920s,

but the foundation was still there along

with three outbuildings in a collapsed

barn.

She parked near a historical

marker that mentioned the Collier family

in passing, noting only that they had

been prominent planters in the

reconstruction era.

Nothing about labor

practices, nothing about the people who

had worked this land.

Chambers walked the property with her

camera.

The outuildings were wood-frame

structures, weathered gray and leaning.

She pushed open the door of the smallest

one, a single room about 12x 12 ft.

The

windows were boarded over, but gaps in

the planks let in enough light to see.

The interior walls still had metal

brackets bolted into the studs.

She ran

her hand over one.

It was positioned at

about shoulder height.

Another was lower

near the floor restraints or the

fittings for bars.

She photographed

everything.

The brackets, the door,

which had a hasp for an external

padlock, the window frames, which still

showed drill holes where something had

been mounted.

When she stepped back

outside, she noticed the building sat in

direct line of sight from where the main

house had been.

Someone standing on that

ver could have looked across the yard

and seen this structure clearly.

Back in

Jackson, Chambers contacted the

Mississippi Department of Archives and

History.

She wanted to see property

records, tax roles, and any surviving

correspondents from the Collier family.

The archive had a small collection

donated in the 1960s by a Collier

descendant.

It included household

account books from 1872 to 1880.

The

ledgers were meticulous.

Samuel Collier

had recorded every expense, every bail

of cotton sold, every tool purchased.

He

also recorded payments to laborers,

though the amounts were surreal.

For the

year 1876, the ledger showed Ida Collier

credited with $18 in wages, but it also

showed deductions.

$12 for housing, $8

for food, $4 for clothing, $3 for

medical care.

The balance was negative,

$9.

The entry noted this amount would

carry forward to the next year.

It was a

system designed to ensure debt never

ended.

As long as Ida owed money, she

could not leave.

and the terms of what

she owed were set entirely by the person

she owed it to.

Chambers found similar

entries for the other black workers in

the household.

James Collier, listed in

the 1870 census as 19, had a running

debt of $47 by the end of 1876.

Rose

Collier owed $31.

Even Peter, the

9-year-old, had a debt of $6 recorded

against his name.

There was something

else in the ledger.

In the margin of the

page for August 1876, Samuel Collier had

written a note commissioned more for

family portrait paid $12 portrait to be

sent to Thomas at university.

The photograph had been made as a

keepsake for the eldest son who was away

at school.

It was meant to show him the

home he would inherit, the family he

belonged to, and the system of control

that sustained it all.

The bars in the

window were not a mistake.

They were

part of the world.

The Collers believed

they had a right to maintain.

Chambers

knew this evidence would be difficult

for people to accept, not because it was

unclear, but because it implicated

institutions that still held power.

Mississippi in the 1870s was not a rogue

operation.

It was a legal framework.

Sheriffs enforced it.

Courts legitimized

it.

Newspapers ignored it.

The violence

was bureaucratic, which made it durable.

She scheduled a meeting with the

Mississippi Heritage C Center’s board of

directors.

She brought the photograph,

the ledger scans, the court record, and

Harris’s research on vagrancy law

enforcement in Warren County.

She laid

it all out on the conference table.

The

room was silent for a long time.

Finally, Margaret Trent, the cent’s

executive director, spoke.

This is a

significant find, but we need to be

careful about how we present it.

The

Collier family still has descendants in

Vixsburg.

Some of them are donors.

We do

not want to create the impression that

we are attacking anyone personally.

Chambers kept her voice level.

I am not

attacking anyone.

I am describing what

this photograph shows.

If we display it

the way it has been displayed in the

past as a quaint example of southern

domestic life.

We are lying.

We are

erasing Ida and everyone else in that

household who had no choice about being

there.

Another board member, an attorney

named Robert Landry, leaned forward.

But

can we prove they had no choice? The

court record shows a labor contract that

was legal at the time.

We could be

accused of imposing modern values on a

historical situation.

The bars, Chambers

said.

Explain the bars.

Landry did not

answer.

Dr.

Harris, who had been invited

to attend, spoke up.

The legal structure

of page relied on the fiction of

consent.

People signed contracts.

Yes,

but those contracts were enforced by

sheriffs who arrested anyone who left,

by judges who ruled in favor of

landowners, and by a climate of terror

that made real freedom impossible.

The bars are not metaphorical.

They are

literal.

Ida was imprisoned.

Another silence.

Trent looked at the

photograph again, then at Chambers.

What

do you want us to do?

I want us to tell the truth, Chambers

said.

I want an exhibition that centers

this photograph and explains what it

documents.

I want Ida’s name on the

wall, not just the Kier family name.

And

I want to reach out to any descendants

of the people who were held on that

property and invite them to be part of

how we tell this story.

The board voted.

It was not unanimous, but it passed.

The

exhibition opened 6 months later.

It was

called Behind the Glass: Reconstruction

and the Persistence of Bondage in

Mississippi.

The centerpiece was the

1876 photograph displayed large on the

main wall with the window reflection

enlarged beside it.

The label identified

everyone in the image by name, including

Ida.

It explained the legal systems that

allowed her imprisonment.

It quoted from

the ledger showing the debt structure.

It reproduced the court record.

Chambers

and Harris worked with a sum

genealogologist to trace Ida’s family

line.

They found a great great

granddaughter named Patricia Marorrow

living in Detroit.

Marorrow had never

heard of Ida.

Her family’s history had

gaps.

Stories that stopped abruptly in

the 1870s and picked up again decades

later in Memphis and Chicago.

When

Chambers sent her the photograph in the

documentation, Marorrow called her

crying.

“I always knew something

happened,” Marorrow said.

“My

grandmother used to talk about people

who could not leave Mississippi, people

the family lost track of, but she never

had details.

This is the first time I’ve

seen any of them.

Maro flew to Jackson for the exhibition

opening.

She stood in front of the

photograph for a long time, staring at

Ida’s face.

Later, she spoke at a panel

discussion.

She talked about what it

meant to recover a name, to see an

ancestors image to understand that

survival had required navigating a

system designed to destroy her.

She

talked about anger, but also about

pride.

Ida had tried to escape.

She had

resisted.

The exhibition drew protests

from some Collier descendants.

They

argued the display was unfair, that it

judged their ancestors by contemporary

standards, that the family had been good

employers who provided housing and care.

They pointed to the ledger entries

showing food and clothing provided.

They

said the bars might have been for

protection, not imprisonment.

But the

evidence was clear, and the center stood

by it.

The photograph remained on

display.

School groups came through.

Teachers used it in lessons about

reconstruction, labor history, and civil

rights.

Journalists wrote about it.

It

became impossible to look at that image

and see anything other than what it was.

A document of violence disguised as

domesticity.

Chambers returned to the photograph

often over the next year.

She studied

other images in the archive with new

attention.

She found more examples of

families posing with black workers in

ways that suggested control, not

employment.

hands positioned in

unnatural ways as if bound.

Expressions

of fear or exhaustion that did not match

the supposed respectability of the

scene.

Backgrounds that showed locked

doors, fences, overseers standing just

out of frame.

She began to see the

archive differently, not as a neutral

record of the past, but as a gallery of

evidence.

Every photograph was a choice.

Where to stand, what to show, what to

include or exclude.

And in the 1870s

south, those choices often centered on

making exploitation look normal, making

bondage look like care, making violence

look like order.

There were thousands of

photographs like the Kier family

portrait.

Most had never been examined

closely.

Most had labels that repeated

the old stories, the sanitized version

of history that protected powerful

families and erased the people they

harmed.

Chambers realized her work was

just beginning.

She published an article

in the journal of southern history

titled reading reflections visual

evidence of post-emancipation

imprisonment in domestic photography.

It became one of the most cited pieces

in the field.

Other historians began

reaching out with images they had found.

Photographs that seemed ordinary until

you looked at the windows, the corners,

the spaces where power and resistance

left their marks.

Old photographs are

not neutral.

They are arguments about

who mattered, who had rights, who

deserved to be remembered.

For more than

a century, the Kier family portrait had

been read as a simple document of

prosperity and continuity.

The bars in

the window had been invisible or ignored

or explained away.

But once you see

them, you cannot unsee them.

And once

you understand what they mean, you start

to see the same violence everywhere.

In

the posed stiffness of people who could

not leave.

In the background objects

that suggest surveillance and control.

In the faces of children who should have

been free but were not.

Ida’s story is

not unique.

Across the south thousands

of black workers were trapped in systems

of debt pionage, convict leasing, and

forced labor that lasted well into the

20th century.

Most left no photographs.

Most left no names.

But in rare cases,

someone made a mistake.

Someone let the

truth slip into the frame.

And now, if

we are willing to look, we can see it.

Chambers still has the photograph on her

office wall.

Not the sanitized version,

but the one with the reflection enlarged

and labeled.

When students ask her what

she does, she points to it.

I look for

what people tried to hide, she says.

And

then I make it visible again.

Because

every old portrait in every museum,

every family album, every textbook is a

chance to ask, “Who is missing from this

image? Who is behind the glass? And what

did it cost them to stand there while

the camera clicked?

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load