I.

The Photograph That Hid a Century of Pain

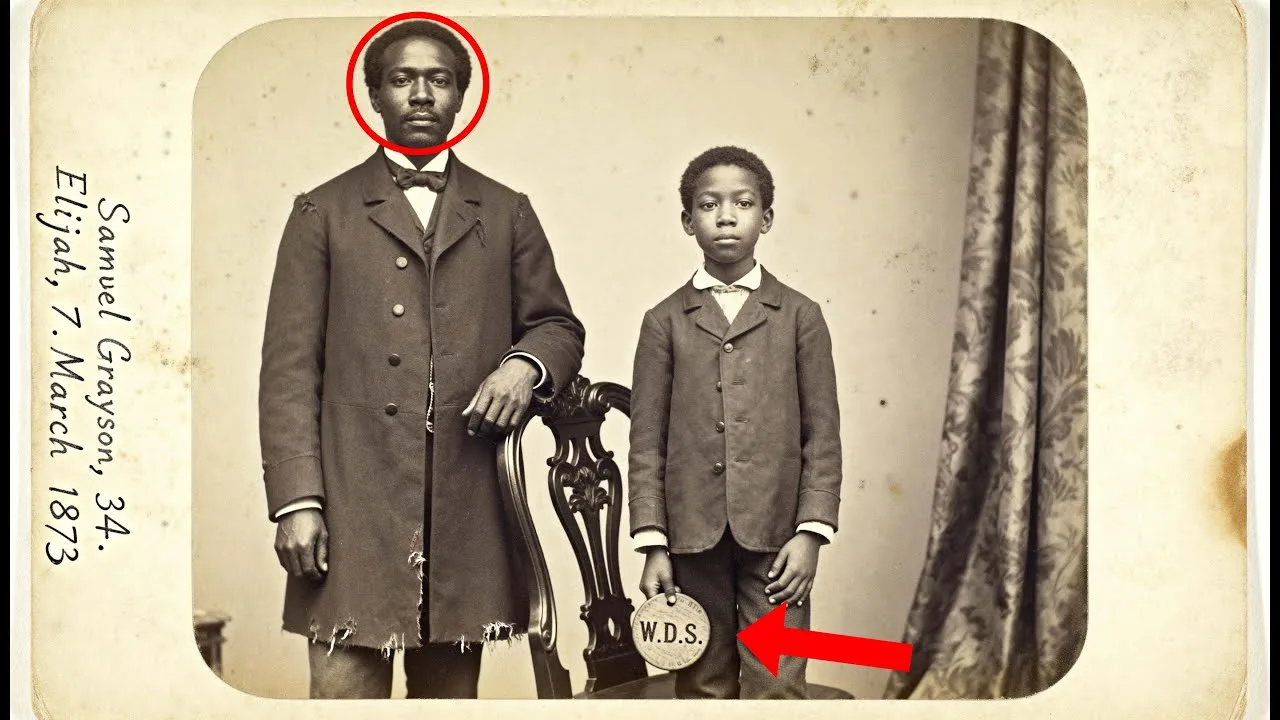

At first glance, the sepia portrait looks like hundreds of others from the era—a proud father, a small boy, a quiet moment frozen in time.

Yet, if you look closely, you’ll see something in the child’s hand.

Something that should not be there.

And once you see it, you cannot look away.

For Duranne Cole, senior curator of photographic archives at a historical society in Columbia, South Carolina, this was just another donation from an estate sale in Charleston.

The family had no living heirs, and the contents of their home—accumulated over a century and a half—were being sold off piece by piece.

Most of the photographs in the dealer’s trunk were unremarkable.

But this cabinet card, measuring roughly 4 by 6 inches and mounted on cream-colored cardstock, caught her attention.

The studio imprint at the bottom read: “J.

Harleston & Co., Charleston.” The image showed a man in his 30s standing with one hand resting on the back of a wooden chair, dressed in a simple but clean wool coat and a white shirt buttoned to the throat.

His expression hovered between solemnity and something harder to name—pride, perhaps, or defiance.

Beside him stood a boy of maybe seven or eight, dressed similarly, his small frame rigid from holding still for the long exposure.

It was a handsome portrait.

The lighting was good.

The composition was balanced.

Duranne almost set it aside.

Then she noticed the boy’s left hand, gripping a small circular object pressed against his thigh, as if he’d been told to hold it but also to keep it out of sight.

She tilted the card toward the lamp and made out the shape—a wooden disc, roughly the size of a silver dollar, with letters stamped into its surface.

Three letters.

She reached for her magnifying loupe and leaned closer.

The letters came into focus slowly: WDS.

Duranne frowned.

She’d seen tokens before—trade tokens, company scrip, commemorative medallions—but this one didn’t match any pattern she recognized.

And the way the boy held it, half hidden, half displayed, suggested it wasn’t a prop chosen by the photographer.

It was something he’d brought with him, something he’d been told to keep.

She turned the card over.

On the back, in faded pencil, someone had written a date: March 1873.

And below that, two names: Samuel Grayson, age 34.

Elijah Grayson, age seven.

Duranne set the photograph down and stared at it for a long moment.

The faces stared back, patient and unreadable.

Something here was wrong, she thought.

And I need to know what.

II.

The Token’s Secret

Duranne Cole hadn’t set out to become an investigator of buried histories.

She trained as an art historian, specializing in American visual culture of the 19th century.

Her dissertation examined the role of photography studios in constructing middle-class identity in the postbellum South.

She understood how these images worked, how they were staged, how they lied.

But this photograph was different.

Samuel and Elijah Grayson were Black.

The studio, J.

Harleston & Co., was one of a handful of Black-owned photography businesses operating in Charleston during Reconstruction.

Duranne knew the name—she’d encountered Harleston’s work before, mostly portraits of Charleston’s small Black elite: ministers, teachers, businessmen, women in their Sunday best.

These images were acts of self-determination, assertions of dignity in a world that denied it at every turn.

But Samuel Grayson didn’t look like the prosperous subjects she usually saw in Harleston’s work.

His coat was worn at the elbows.

His shoes, just visible at the bottom of the frame, were scuffed and cracked.

He was not a man of means.

He was a man who had scraped together what he had to sit for this portrait.

Why? And what was that token in his son’s hand?

Duranne began with the obvious steps.

She checked city directories for Charleston in the early 1870s and found a Samuel Grayson listed in the 1872 directory as a laborer, with an address on a street lost to urban renewal in the 1960s.

She searched census records and found the Grayson household in the 1870 census—Samuel, his wife Louisa, and three children, including a son named Elijah, born around 1866.

The family had been enslaved before the war, their birthplace listed as a plantation in Berkeley County, 20 miles north of Charleston.

So far, a common story—a family emerging from bondage, trying to build a life in the chaos of Reconstruction.

But the token nagged at her.

She’d never seen anything quite like it.

The letters WDS meant nothing.

She reached out to a colleague in Atlanta, Dr.

Clarence Odum, a historian specializing in the economic systems of the postwar South.

She sent him a high-resolution scan of the photograph and asked if he recognized the token.

His reply came three days later and changed everything.

> “I’ve seen tokens like this before,” Clarence wrote.

“They were issued by commissary stores, mostly in rural areas but sometimes in cities, too.

Freed people working under crop lien contracts were often paid not in cash, but in credit at company stores.

The tokens were like currency, but they could only be spent at the store that issued them.

The letters would be the initials of the store owner or the plantation.

WDS could be a lot of things, but if this family was from Berkeley County, I’d start looking there.”

Duranne pulled up records of Berkeley County businesses from the 1870s.

Hours of searching finally found a match: WDS—William Dri Sinclair, proprietor of a general store and cotton buyer operating out of Pineville.

Sinclair made a fortune after the war by extending credit to freed people, allowing them to purchase seeds, tools, clothing, and food on account, with the debt to be repaid at harvest time.

The system was legal.

It was also, as Duranne soon discovered, a machine for perpetual servitude.

III.

Debt as Bondage

Duranne drove to Berkeley County the following week.

Pineville was barely a town anymore—just a gas station, a church, and a few clapboard houses.

But the county courthouse in nearby Moncks Corner held records going back to the 1820s.

The clerk was skeptical at first.

Researchers came through sometimes, usually genealogists tracing family trees.

But Duranne’s request was unusual—she wanted crop lien contracts, debt ledgers, any records connected to William Dri Sinclair’s store.

It took two days of searching, but she found them.

Stacks of yellowed paper bound with twine documenting decades of transactions.

Among them she found a name that stopped her cold: Samuel Grayson.

Contract dated February 1871.

Sinclair had advanced him $47 in credit to be repaid with interest at the end of the harvest.

The terms were predatory—25% interest compounded monthly, with Sinclair as the sole arbiter of the value of Grayson’s cotton crop.

If the harvest was poor, or if Sinclair decided the cotton was worth less than expected, the debt would roll over into the next year, and the next, and the next.

But that was not the worst of it.

Attached to the contract was a second document: a security agreement listing in cold legal language the collateral Samuel Grayson had pledged against his debt—one mule, one plow, household furnishings, and on the final line: “services of minor child Elijah Grayson, age five, to be rendered to creditor in the event of default until such time as debt is discharged.”

Duranne read the line three times, feeling something tighten in her chest.

The token in the boy’s hand was not a keepsake.

It was not a memento.

It was a marker of ownership—a claim on his labor, his body, his future.

If Samuel Grayson could not pay his debt, his son would be taken.

She thought of the photograph again—the father’s expression hovering between pride and something darker, the boy’s rigid posture, his small hand gripping the wooden disc.

Had Samuel known what it meant? Had he understood what he had signed, or had he been told it was just a formality, just a piece of paper, just a token?

IV.

Slavery by Another Name

The crop lien system that ensnared the Grayson family was not an accident.

It was the deliberate creation of a Southern economy that refused to let go of its old hierarchies.

After the war, freed people had been promised land, education, and the rights of citizenship.

But the promise was betrayed almost before it was made.

The Freedmen’s Bureau, understaffed and underfunded, could not enforce contracts or protect workers from fraud.

State legislatures, dominated by former Confederates, passed laws criminalizing unemployment and allowing sheriffs to arrest Black men for vagrancy and lease them out to planters.

Merchants like Sinclair found a way to rebuild the old system—without technically owning anyone.

Duranne consulted Dr.

Lorraine Dubois, a legal historian in New Orleans who spent years studying the crop lien system.

Lorraine confirmed what Duranne had begun to suspect: the security agreements that pledged children as collateral were not rare.

They were common, especially in the first decade after emancipation when freed people had no property, no savings, and no access to legitimate credit.

> “The planters and merchants understood something very simple,” Lorraine explained.

“If you control a man’s debt, you control his labor.

And if you control his children, you control his future.

These contracts were designed to be unpayable.

The interest rates were usurious.

The accounting was opaque.

And if a family tried to leave, they could be arrested for fraud or theft.

It was slavery by another name.”

Duranne asked about enforcement.

What happened when a father defaulted? What happened to the children?

> “That’s where it gets murky,” Lorraine said.

“The courts were inconsistent.

Some judges refused to enforce these contracts.

Others treated them as binding.

And in many cases, enforcement happened outside the courts entirely.

Merchants had relationships with local sheriffs, with planters, with labor agents.

If a man owed a debt and could not pay, his children might simply disappear—sent to work on a farm somewhere, apprenticed to a factory, or worse.

The records are incomplete because no one wanted to keep records.

This was the kind of thing people did quietly in the margins.”

V.

What Happened to Elijah Grayson?

Duranne thought of Elijah Grayson standing in that Charleston studio, gripping his wooden token.

What had happened to him? Had Samuel managed to pay the debt? Had the family escaped? Or had the boy been taken, swallowed up by a system that treated children as currency?

She went back to the records.

The ledgers from Sinclair’s store told a grim story.

Samuel Grayson’s debt had grown every year—$47 in 1871 became $63 in 1872, then $81 in 1873, then over $100 by 1874.

The interest compounded relentlessly, and no matter how much cotton Samuel produced, Sinclair always valued it just low enough to keep the debt alive.

By 1875, the entries for Samuel Grayson stopped.

Duranne searched for him in other records.

She found a death notice in a Charleston newspaper from August 1875.

Samuel Grayson, aged 36, had died of consumption—what would now be called tuberculosis.

He left behind a widow, Louisa, and three children.

Then, in the same ledger where she found the original contract, Duranne found a new entry:

September 1875.

Transfer of security to W.D.

Sinclair.

One minor child, Elijah Grayson, age 9.

Value credited against debt: $35.

Duranne stared at the line until her vision blurred.

$35.

That was the price of a nine-year-old boy in 1875—a decade after emancipation, in a country that had fought a war to end slavery.

$35 credited against his dead father’s debt—not even enough to clear the balance.

She searched for Elijah in every record she could find—census rolls, school registers, church memberships, court filings.

For years, he was invisible.

Then, in the 1880 census, she found a boy named Elijah, age 14, listed as a farm laborer on a property in Dorchester County, 50 miles from Charleston.

The head of household was listed as Thomas Sinclair, William Dri Sinclair’s brother.

Elijah had not disappeared.

He had been transferred like a piece of equipment from one Sinclair to another.

Duranne wanted to believe the story ended there—with Elijah growing up, escaping, building a life of his own.

But the records told a different story.

Elijah Grayson appeared in the 1890 census as a laborer on the same property.

In 1900, he was still there.

In 1910, still there, now listed as age 44, still working the same land his father had worked, still caught in the same web of debt and dependency that had claimed his childhood.

He had never gotten out.

VI.

Telling the Truth, Despite the Silence

When Duranne brought her findings to the historical society’s board, the response was not what she expected.

She prepared a detailed presentation—the photograph, the token, the contracts, the ledgers, the census records, the whole terrible arc of the Grayson family’s entrapment.

She expected shock, outrage, perhaps debate about how to present this material to the public.

What she got instead was silence, followed by careful questions about context and interpretation.

The board chair, a retired banker named Harold Whitmore, spoke first.

> “This is certainly compelling research, Dr.

Cole, but I wonder if we’re being a bit hasty in our conclusions.

These contracts were common at the time, weren’t they? Part of the normal business practices of the era.”

“They were common,” Duranne said.

“That’s precisely the point.

This wasn’t an aberration.

It was a system—a legal framework designed to recreate the conditions of slavery without using the word.”

“But surely we can’t hold 19th-century merchants to 21st-century standards,” another board member interjected.

“Sinclair was operating within the law.”

“The law was designed to enable exploitation,” Duranne replied.

“That’s what the research shows.

The crop lien system was a deliberate mechanism for keeping freed people in bondage.

And this photograph, this token, is evidence of how it worked at the level of individual families.

We have a chance to tell that story.”

The room shifted uncomfortably.

Someone coughed.

Harold Whitmore shuffled his papers.

> “The thing is,” he said slowly, “the Sinclair family is still quite prominent in the Low Country.

William Dri Sinclair’s descendants have been, well, generous supporters of several institutions in the region, including this one.

I’m not saying we shouldn’t pursue this research, but perhaps we should be thoughtful about how we frame it.

Perhaps we should consult with the family before we make any public claims.”

Duranne felt the temperature in the room drop.

She understood now.

This was not about historical accuracy.

It was about money, reputation, and the careful management of uncomfortable truths.

> “The Grayson family has descendants, too,” she said quietly.

“I’ve been trying to trace them.

Elijah had children.

Those children had children.

Somewhere out there, people are walking around who don’t know what happened to their ancestors.

Who don’t know that their great-great-grandfather was pledged as collateral for a debt he never incurred.

Don’t they deserve to know?”

The silence stretched.

Finally, Dr.

Yolanda Ree, a professor of African-American studies, spoke up.

> “Dr.

Cole is right.

If we bury this research to protect the feelings of a wealthy white family, we’re participating in the same erasure that happened in 1875.

We’re choosing the Sinclairs over the Graysons, just like the courts did, just like the system did.

Is that really who we want to be?”

The meeting ended without a resolution.

But Duranne knew she couldn’t wait for the board to make up its mind.

She began reaching out to journalists, documentary filmmakers, academic conferences—and she kept searching for the Grayson descendants.

VII.

Finding the Graysons

It took six months, but she found them.

Elijah Grayson had married in 1892 and had four children.

His youngest son, named Samuel after the grandfather he never knew, moved to Philadelphia in 1920, part of the Great Migration that carried millions of Black southerners out of the Jim Crow South.

Samuel’s daughter, Ruth, was still alive, 93 years old, living in a nursing home in West Philadelphia.

Duranne called ahead and explained who she was and what she’d found.

Ruth’s granddaughter, Denise Grayson Williams, agreed to meet.

They sat in Ruth’s small room, surrounded by photographs and potted plants.

Ruth was frail but sharp-eyed, her voice thin but steady.

Denise held her grandmother’s hand as Duranne laid out the documents, the contracts, the ledger entries, the census records.

When she reached the photograph of Samuel and Elijah, Ruth leaned forward and stared at it for a long time.

> “That’s my grandfather,” she said.

“I never saw a picture of him before.

My father talked about him sometimes, said he worked himself to death on a farm that was never his.”

“He was taken as a child,” Duranne said gently.

“His father’s debt was used as an excuse to keep him in bondage.

The token in his hand—we believe that was a marker, a way of identifying him as collateral.”

Ruth closed her eyes.

> “They stole him,” she said.

“They stole his whole life.”

Denise squeezed her grandmother’s hand.

> “What happened to the people who did this?” she asked.

“The Sinclairs? They prospered,” Duranne said.

“Their descendants are still wealthy, still respected.

They’ve never acknowledged any of this.”

Ruth opened her eyes.

> “Then we make them acknowledge it,” she said.

“We tell the story.

We put it where people can see it.

We don’t let them forget.”

VIII.

The Truth on Display

The exhibition opened 14 months later.

The historical society, pressured by media attention and a petition signed by over 2,000 people, agreed to host it.

The photograph of Samuel and Elijah Grayson occupied the center of the main gallery, enlarged to nearly life-size, with the token in Elijah’s hand highlighted and explained in a detailed panel.

The exhibition traced the whole system—the crop lien contracts, the security agreements, the ledgers, the transfers.

It named names: William Dri Sinclair, Thomas Sinclair, the judges who enforced the contracts, the sheriffs who carried out the seizures.

And it named the victims: Samuel Grayson, who died in debt; Elijah Grayson, who spent his childhood as collateral and his adulthood as a laborer on land his captors owned; Louisa Grayson, who lost her husband and her son and left no record of her grief.

Ruth Grayson did not live to see the opening.

She passed away three weeks before, at 94, surrounded by her family.

But Denise Grayson Williams stood at the entrance on opening night, greeting visitors, answering questions, telling her family story.

> “People ask me if I’m angry,” she said in an interview.

“And I am, but mostly I’m just—determined.

My great-great-grandfather was a child.

He didn’t have a choice.

He didn’t have a voice.

Now we’re giving him one.

Now we’re saying his name out loud.

That matters.

That changes something.”

The Sinclair family issued a brief statement expressing regret for the painful legacies of the past and announcing a donation to a scholarship fund for descendants of freed people in Berkeley County.

They did not attend the exhibition.

They did not meet with the Grayson family.

They did not acknowledge in any public form what their ancestors had done.

But the records were there now in a climate-controlled archive, available to any researcher.

The photograph was there in a museum, with a label that told the truth.

And the story was there in newspapers, documentaries, and academic journals—harder to ignore, harder to forget.

IX.

The Power of Photographs—and the Stories They Hide

Duranne Cole returned to her work.

She cataloged more photographs.

She processed more donations.

But she looked at them differently now.

Every smiling face, every proud pose, every carefully arranged tableau.

She asked herself, “What is this image hiding? Whose labor made this moment possible? Whose suffering is cropped out of the frame?”

Old photographs are not neutral documents.

They are artifacts of power, shaped by the people who could afford cameras and studios, who could decide how they would be seen by posterity.

But sometimes, if you look closely enough, you can see the cracks—a hand gripping something it should not hold, an expression that does not match the pose, a detail that whispers quietly but persistently that the story you’ve been told is not the whole story.

The wooden token in Elijah Grayson’s hand was never meant to be seen.

It was supposed to be invisible—a private claim on a child’s future, hidden in plain sight.

But the camera caught it anyway.

And 150 years later, it became the key that unlocked a buried history.

There are thousands of photographs like this one, scattered in attics, archives, and antique shops across the country.

Family portraits that look respectable, heartwarming, ordinary.

Most of them will never be examined closely.

Most of their secrets will stay buried.

But every now and then, someone picks one up.

Someone notices the detail that does not fit.

Someone asks the question that should have been asked a century ago.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load