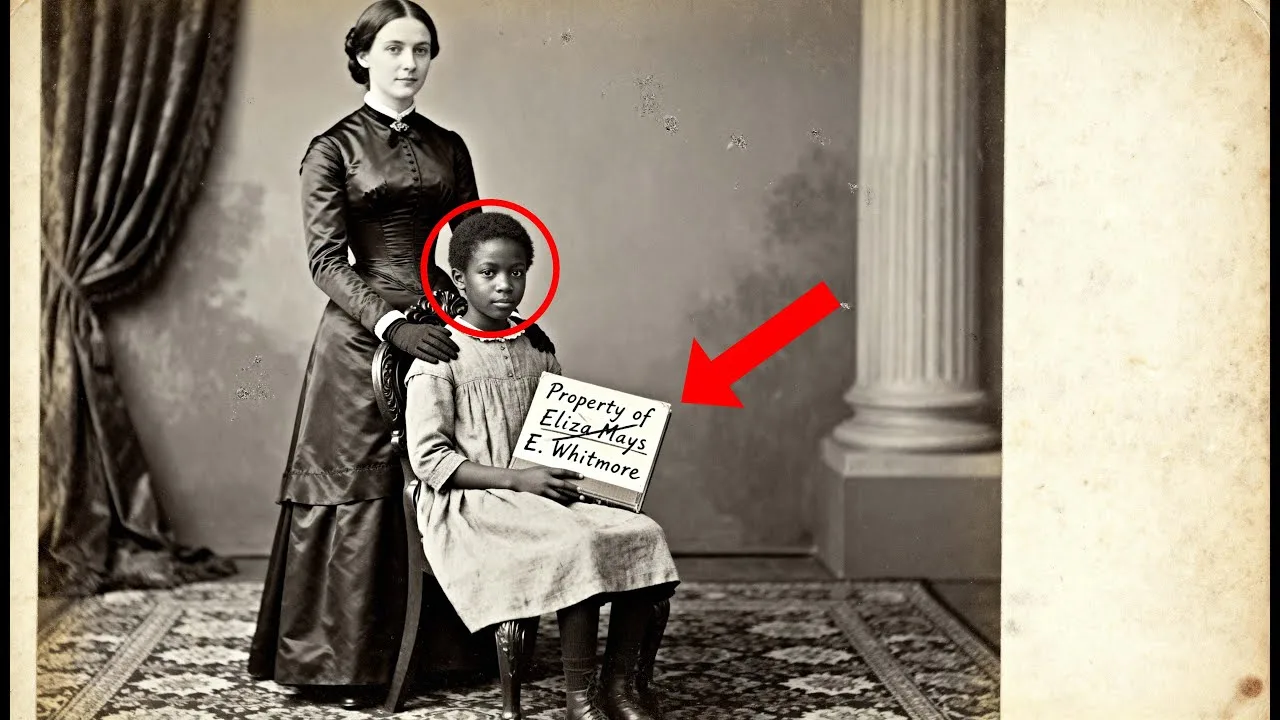

This 1858 studio portrait looks elegant until you notice the shadow.

It arrived at the Louisiana Historical Collection in a leather album donated by a family clearing their grandmother’s estate.

The couple looked prosperous.

Their daughter stood between them with perfect posture, and the painted balcony behind them suggested wealth without being gaudy.

But Dr.

Maya Reeves, a curator who had examined thousands of antabbellum photographs, could not stop looking at the lower left corner of the frame.

There was a shadow there that didn’t match anything in the composition.

Reeves had worked at the collection for 9 years.

She specialized in dgerotypes and early paper prints from the Gulf Coast, and she knew that studio photographers in the 1850s controlled every element of their images with obsessive care.

light, pose, backdrop, even the tilt of a subject’s chin.

Nothing appeared by accident.

So when she first cataloged this particular cart to visit on a Wednesday afternoon in March, she assumed the shadow was a dark room error, a stray smudge from the printing process.

She logged it, set it aside, and moved on to the next batch.

But 3 days later, she found herself pulling the photograph out again.

The shadow fell across the lower portion of the painted balcony backdrop, just where the decorative iron work met the studio floor.

It was child-sized, small, and distinct.

The angle suggested a figure standing to the far left outside the main frame, but there were only three people in the photograph.

The father stood on the right in a dark coat with brass buttons.

The mother sat in the center, her hands folded over a lace shaw.

Their daughter, perhaps 6 years old, stood between them in a white dress with a dark sash.

Her face solemn in the way children’s faces always look solemn in long exposure portraits.

Three people, four shadows.

Reeves brought the image to a light table and adjusted the magnification.

The shadow was not a smudge.

It had weight, form, the curve of a small head and shoulders.

She could even make out what looked like the faint outline of a skirt or dress.

Whoever cast that shadow had stood in the studio long enough for the camera to register their presence, but they were not in the finished print.

She turned the photograph over.

On the back, in faded brown ink, someone had written Devo family, JM Lauron Studio, Royal Street, June 1858.

She didn’t sleep much that night.

The next morning, she started making calls.

Maya Reeves came to archival work through a ciruitous route.

She had studied art history at Howard, spent two years at the Shamberg Center learning conservation techniques, then moved south to work on plantation documentation projects.

She had handled images of enslavers posing with people they claimed as property, children sold at auction, families torn apart in estate divisions.

She thought she had seen every permutation of how power used the camera to assert itself.

But this shadow felt different.

It was not a person reduced to an object in plain view.

It was a person reduced to nothing, erased from the image, but still present in the light.

She began with the studio itself.

JM Lauron had operated on Royal Street in the French Quarter from 1854 to 1862.

His advertisements in the Daily Pikune promised lifelike portraits of unmatched clarity and discretion for families of distinction.

City directories listed him at 428 Royal until the federal occupation, after which the trail went cold.

She found three other Lauron portraits in the collections database, all showing similar technical precision, crisp focus, careful lighting, expensive backdrops.

He was a photographer who catered to New Orleans elite, the sugar planters and cotton brokers who wanted images that projected respectability and permanence.

The magnifying glass revealed more.

In the upper right corner of the photograph, barely visible, was Lauron’s studio mark, a tiny embossed seal showing a camera on a tripod.

Below that, etched into the plate before printing, were two sets of numbers.

The first was easy, 06 warm fiend 58, the date.

The second was harder to parse, a series that read 4111.

She had seen similar notations on other studio portraits from this period.

Photographers kept logs of their clients, numbered the plates, tracked orders, and reprints.

But what did four separate ones mean? She pulled the Devo family file from the reading room.

The donation paperwork listed the family as prominent merchants with holdings in sugar and real estate.

The photograph had come with a small trove of letters, deeds, and account books spanning three generations.

Most of it was routine business correspondence and household expenses, but tucked in a leather folio, she found a handwritten studio invoice dated June 1858.

It listed charges for one family portrait, four subjects, balcony backdrop, three prints on card stock.

The total came to $12, a significant sum for the time.

Four subjects, three people in the photograph.

She showed the invoice to Dr.

Ethan Brousard, a historian at Tulain, who had published extensively on slavery in Antabbellum, New Orleans.

They met in his office on a Friday afternoon.

The photograph and invoice spread across his desk.

He studied both for a long time without speaking.

When he finally looked up, his expression was careful.

The kind of careful that meant he was about to say something he wished he did not have to say.

“You know what page means?” he asked.

“She did.” It referred to the formalized arrangements between white men and free women of color in New Orleans.

Relationships that existed in a legal gray zone producing families that could inherit property but never full legitimacy.

This is not that, Brousard said.

But it is adjacent.

Look at the invoice again.

Four subjects photographed, but only three appear in the final print.

That was not an error.

That was a choice.

He pulled a thin volume from his shelf.

uh privately published memoir by a mixed race photographer who had worked in New Orleans in the 1870s.

The man described how white studios in the 1850s had occasionally photographed enslaved children alongside the white families who owned them, not as family members, but as proof of property.

Parents wanted documentation of valuable assets, particularly light-skinned children who could be sold at premium prices.

But they also wanted respectable portraits for display in their parlors and to send to relatives.

So photographers developed a practice.

Take the full composition with all subjects present, make one print for the records, then reposition the plate or crop the negative and make separate prints with the enslaved children removed.

It saved time, Brousard said quietly.

One sitting, multiple products.

The family got their gentiel portrait.

The studio kept the full image in the ledger in case ownership was disputed or the child needed to be identified later, and the children themselves were rendered invisible in the version that mattered socially.

Reeves felt something cold settle in her chest.

She looked at the shadow again.

That child had stood in the studio, stood still for 30 or 40 seconds while the chemicals captured their image, stood in their best clothes, or perhaps clothes chosen for them while a photographer arranged the lighting and the Devo family posed.

And then through some manipulation of the printing process, they had been erased from the final version, turned into a ghost, a shadow without a body.

“Can you tell if that is what happened here?” she asked.

You would need the original plate or negative, Brousard said.

Or the studio’s record book if it still exists.

But that shadow, that is what happens when someone stands in frame during exposure, but gets cropped or masked during printing.

The light still remembers them.

The search for Lauron’s studio records took 3 weeks.

Reeves contacted archives across Louisiana, checked museum collections in Mobile and Savannah, even reached out to descendants of French Quarter photographers whose families might have acquired Lauron’s materials when he disappeared in 1862.

Most trails ended in dead ends.

Studios changed hands.

Floods destroyed basement.

Fires consumed warehouses.

The visual record of the Civil War South was fragmentaryary at best, and business records were even more ephemeral.

But she got lucky.

At the New Orleans Notarial Archives, a reference librarian remembered a deposit from the 1950s, a box of miscellaneous studio materials donated by a salvage company that had cleared out a Royal Street building.

The box had never been fully cataloged.

It sat in climate controlled storage, its contents listed only as photographic ephemera, various studios.

C1 18501 1880.

Reeves went through it on a Tuesday morning with archival gloves and a tablet for notes.

There were glass plates wrapped in old newspaper, envelopes of faded prints, scraps of painted backdrops, and three leather bound ledgers.

The second ledger had JM Laurent’s name embossed on the cover.

She opened it carefully.

The pages were brittle, the ink brown with age, but the handwriting was meticulous.

Lauron had logged every session.

Client name, date, number of subjects, backdrop choice, number of prints ordered, and price.

Each entry had a reference number.

She paged through to June 1858 and found it.

Devo family, June 14th, four subjects, balcony backdrop, three card stock prints, $12.

In the margin, in smaller script, Lauron had written child 4 cropped per client request, full plate retained.

Below that entry was another line added later in different ink.

Child 4 sold J.

Bowmont agent July 2nd 1858.

Reeves sat back.

The room felt very quiet.

She checked the date again.

18 days between the photograph and the sale.

She pulled the Devo account books from the historical collection and cross- refferenced July 1858.

There it was, a single line in the household expenses ledger.

Payment received, one Mulatto girl, age estimated 9 years, sale to J.

Bowmont factor for transport, some $620.

No name, no further details, just a line in a ledger that marked a child as transferred property.

A child whose shadow had been captured in silver salts and chemistry, but whose face would never be seen by anyone viewing the Devo family portrait.

The system Reeves uncovered was not unique to Laurent studio, though his records provided the most detailed documentation.

She found references to similar practices in the archives of two other New Orleans photographers and in the memoir of a Charleston portraitist who had fled north during the war.

The logic was consistent.

Enslaved children, particularly those with lighter skin, represented significant financial assets.

Families wanted proof of ownership, wanted documentation for insurance or estate purposes.

But those same families also wanted images of themselves that conformed to the aesthetics of gental respectability.

You could not hang a parlor portrait that showed enslaved children standing beside your daughter as if they were equals.

Not if you wanted to maintain the social fiction that slavery was a benevolent institution, that enslaved people were content and childlike, that white families were kind stewards of an inferior race.

So photographers solved the problem with light and chemistry.

They posed everyone together, made the exposure, then manipulated the print to remove the people who complicated the story.

Sometimes they cropped the image.

Sometimes they masked portions of the negative during a second exposure.

Sometimes, as in the Devro portrait, they were sloppy or rushed and a shadow remained, a trace of the presence they tried to erase.

Dr.

Brousard introduced Reeves to Carmen Dile, a genealogologist who specialized in tracking enslaved families through fragmentaryary records.

Dial had spent 15 years reconstructing kinship networks from bills of sale, estate divisions, and church records.

She knew the patterns.

Children separated from parents.

Mothers sold away from sons.

Families broken and scattered as financial instruments.

Their names changed with each transaction.

Their histories deliberately obscured.

The shadow child, Dile said when Reeves showed her the photograph in the studio ledger.

Give me two weeks.

She worked through the Bowmont factor records first.

Jacqu Bowmont had operated a slave trading business on Bon Street from 1851 to 1861, specializing in what the euphemisms of the time called fancy trade, the sale of light-skinned enslaved women and children to buyers in the deep south.

His records partially preserved at Tain’s special collections showed a transaction on July 2nd, 1858.

One girl, age nine, described as bright mulatto, house-trained docsel temperament, purchased from the Devo estate for 620 and resold 2 days later to a plantation outside Natchez for 800.

The markup was typical.

Bowmont took his cut and the child was gone.

The plantation records from Nachez were harder to access.

The property had changed hands multiple times after the war and many of the original documents had been lost.

But Dile found a partial inventory from 1858 in the Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

It listed the names of enslaved people brought onto the property that summer.

Most entries were sparse, just a first name, age, and monetary value, but one caught her eye.

Rose, 9 years, 890, purchased J.

Bowmont factor, July 1858.

Rose, the shadow had a name.

Dile kept digging.

She found Rose again in an 1860 plantation census listed among the house servants.

Then nothing.

The trail went cold after 1862, the year the plantation owner fled ahead of Union troops and the enslaved population scattered.

Some went north.

Some stayed and worked the land as freed people.

Some disappeared into the chaos of war and were never documented again.

There was no death record for Rose, no mention in post-war Freriedman’s bureau files, no signature on a labor contract.

She vanished from the archive the way so many enslaved children vanished, erased by a system that treated them as interchangeable, disposable, unworthy of individual memory.

But the photograph remained and the shadow.

Reeves presented her findings to the Louisiana Historical Collections Curatorial Board on a Wednesday afternoon in June.

She had prepared a 20-page report with images, transcriptions, and contextual analysis.

She projected the Devo photograph on the screen, the shadow visible in the lower left corner.

She walked them through the studio records, the bill of sale, the eraser practices, the brief trace of Rose in the Nachez plantation inventory.

The room was silent when she finished.

The board chair, a retired attorney named Gordon Heert, spoke first.

“This is compelling research,” he said carefully.

But I am concerned about interpretation.

We have a shadow and some circumstantial records.

We do not have definitive proof that the shadow belongs to this specific child or that the Devo family intended any malice.

Studio photographers made errors.

Printing was imperfect.

Could this not be a technical mistake rather than deliberate eraser? Reeves had anticipated this.

The studio ledger explicitly states that child 4 was cropped per client request.

She said that is not an error.

That is a documented choice and the timeline is clear.

Photograph in June, sale in July.

The child was photographed, removed from the family portrait and sold south within 18 days.

Another board member, a museum director named Patricia Melonsson leaned forward.

I do not doubt your research, but we need to consider the implications.

The Devo family has been a donor to this collection for generations.

Their descendants are still active in the community.

If we mount an exhibition suggesting their ancestors participated in this kind of practice, we risk significant backlash.

We could lose funding.

We could lose access to other family archives.

We could also tell the truth, Reeves said.

The debate lasted an hour.

Some board members argued for a softer approach, suggesting they display the photograph with a vague caption about complex social dynamics in Antabbellum, New Orleans.

Others worried about modern sensitivities, about donors uncomfortable with confronting their ancestors participation in slavery.

A few seemed genuinely troubled by the research, but paralyzed by institutional caution.

Only two people spoke unequivocally in support of Reeves’s proposal to build an exhibition around the photograph and its hidden history.

One of them was Dr.

Brousard, who had been invited to provide historical context.

Slavery was not complex.

He said it was brutal, systematic, and lucrative.

This photograph is evidence of how that system worked, how it erased children from visual history while profiting from their bodies.

If we cannot tell that story honestly, we have no business holding these materials.

The other was Vincent Tibido, the collection’s only black board member, a lawyer who had pushed for years to expand the institution’s focus beyond elite white families.

We have been sanitizing this history for too long, he said.

Every time we soften the language, every time we worry more about donor comfort than about the people who suffered, we become complicit in the erasure.

This shadow is the only trace this child left.

Are we really going to ignore it because it makes someone uncomfortable? The vote was close.

5 to four in favor of moving forward with the exhibition.

The exhibition opened 8 months later.

It was small, just one gallery, but the design was deliberate.

Visitors entered through a darkened corridor lined with mirrors, their own shadows cast on the walls by carefully positioned lights.

At the center of the space, the Devo photograph hung alone, illuminated and enlarged to four feet wide.

The shadow in the lower left corner was impossible to miss.

Around the room, text panels explained the research, Laurens studio practices, the cropping notation in the ledger, the bill of sale, the brief appearance of Rose’s name in the Nachez inventory.

Reeves had worked with a graphic designer to create a timeline showing the 18 days between the photograph and the sale.

Each day marked by a small vertical line, the brevity of the interval making the violence feel immediate and cold.

One wall displayed other examples.

Photographs from Charleston, Richmond, and Mobile where careful examination revealed similar traces.

A hand at the edge of a frame that did not match any visible person.

A reflection in a mirror showing someone cropped from the final print.

Studio records mentioning subjects who did not appear in the finished image.

The eraser had been systematic, widespread, and accepted practice among photographers who served the planter class.

But the most powerful element of the exhibition was the voice Reeves and Dile had managed to recover.

They had found a descendant of the Nachez plantation’s enslaved community, a woman named Lorraine Baptiste, whose grandmother had been born on the property in 1857.

Baptist’s family had passed down stories about the house servants, including one about a girl named Rose, who had arrived from New Orleans and worked in the kitchen.

The details were fragmentaryary, passed through oral history over four generations.

But Baptiste remembered her grandmother saying that Rose had been terrified of being photographed again, that she had hidden when a traveling photographer came to the plantation in 1866 to document the formerly enslaved population for Freriedman’s Bureau records.

My grandmother said Rose told her that photographs took pieces of you and made you disappear.

Baptiste said in a recorded interview that played on a loop in the gallery.

I did not understand what that meant until Dr.

Dile showed me this picture.

Until I saw that shadow.

Rose was right.

They took her image and made her disappear.

But the light remembered.

The exhibition drew protests.

The Devo family issued a statement through their lawyer calling the display inflammatory and historically irresponsible.

Two major donors threatened to withdraw funding.

A columnist in the local paper accused the historical collection of weaponizing the past to score political points.

But the exhibition also drew crowds.

Schools brought students.

Scholars came from other states to study the photograph in records.

Descendants of enslaved families stood in the gallery and wept, seeing in that shadow an acknowledgement of what had been taken from their ancestors.

Reeves stood in the gallery one afternoon, 3 months after the opening, watching a group of middle school students examine the photograph.

Their teacher was explaining how cameras worked in the 1850s, how light exposed chemicals, how images were fixed and printed.

One girl raised her hand if they wanted to erase her tied to the girl asked, “Why did they photograph her at all?” The teacher paused.

“That is an excellent question.” Reeves stepped forward.

because she had value as property, she said gently.

The family wanted proof they owned her in case anyone challenged that ownership, but they did not want her to have value as a person.

So, they erased her from the image they showed to the world.

The girl thought about this.

But she is still there, she said, pointing to the shadow.

You can still see her.

Yes, Reeves said.

You can still see her.

The archival work continued.

Dile found two more references to Rose in post-war records, both fragmentaryary.

A Freriedman’s bureau teacher in Natchez mentioned a young woman named Rose who attended a brief school session in 1867 but left after 2 months, destination unknown.

A church register from a black Baptist congregation in Vixsburg listed a rose, age approximately 25, who married a man named Samuel Grant in 1874.

The details were too sparse to confirm identity, but they offered the possibility that Rose had survived, that she had carved out a life in freedom, however difficult and constrained.

The photograph itself became a teaching tool.

Reeves published an article in the Journal of Southern History detailing the studio eraser practices, and the image circulated through academic networks.

Other historians began examining their own collections with new attention, looking for shadows and absences for traces of people deliberately removed from visual records.

A researcher in Virginia found a degara where careful magnification revealed a child’s hand at the edge of the frame.

The rest of the child cropped away.

A curator in South Carolina discovered studio ledgers showing similar notations.

Subjects photographed, subjects removed, subjects sold.

The pattern was undeniable.

The camera, an instrument that supposedly captured truth, had been used to construct lies.

It had documented ownership while erasing personhood.

It had turned children into shadows, into negative space, into evidence of a system that insisted they were property, but could not afford to let them be seen as human in respectable spaces.

Old photographs are not neutral.

They never were.

Every portrait from the antibbellum south is a document of power, a staging of social hierarchy, a claim about who mattered and who did not.

The people who commissioned these images understood that.

They knew that visual representation had weight, that the images they displayed in their homes and sent to their relatives would shape how their families were remembered.

So they controlled the frame.

They decided who would be visible and who would be erased, who would be remembered and who would be forgotten.

But light is stubborn.

It records what it touches and it leaves traces in glass plates and chemical emotions.

In the physical properties of early photography, evidence remains.

Shadows that should not exist.

Reflections that reveal absences.

Studio records that document the gap between what was photographed and what was printed.

These traces are not accidents.

They are the material proof of eraser.

The archive fighting back against the lies it was forced to contain.

Across the country in museums and historical societies and family atticts, there are thousands of photographs from this period.

Portraits of planters and merchants, of families posed in studios and on plantation porches, of children in their Sunday clothes standing beside parents who claim to embody Christian virtue.

And in some of those images, if you look carefully, there are shadows where there should be none.

hands at the edges, reflections in mirrors, traces of people who were there when the camera opened but gone when the image was shared.

Each one is evidence.

Each one is a scar in the visual record.

Each one is a child, a person, a life that someone tried to erase but could not quite eliminate.

The light remembered.

Now we have to remember

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load