The Photograph That Refused to Stay Silent

It was a humid afternoon in June 2019 when Dr.

Miriam Holt, a visual historian at a small research archive in Columbia, South Carolina, found herself hunched over a battered donation box.

The box was filled with the usual: sepia portraits, faded views of plantation houses, stern ancestors in Sunday clothes.

The Rawlings family, whose estate provided the collection, had roots stretching back to the colonial rice plantations of Georgetown County.

Most images seemed destined for a quiet life in local history museums, captioned with a sentence or two about Reconstruction and progress.

But one photograph, tucked into an unmarked envelope at the bottom of the box, made her stop.

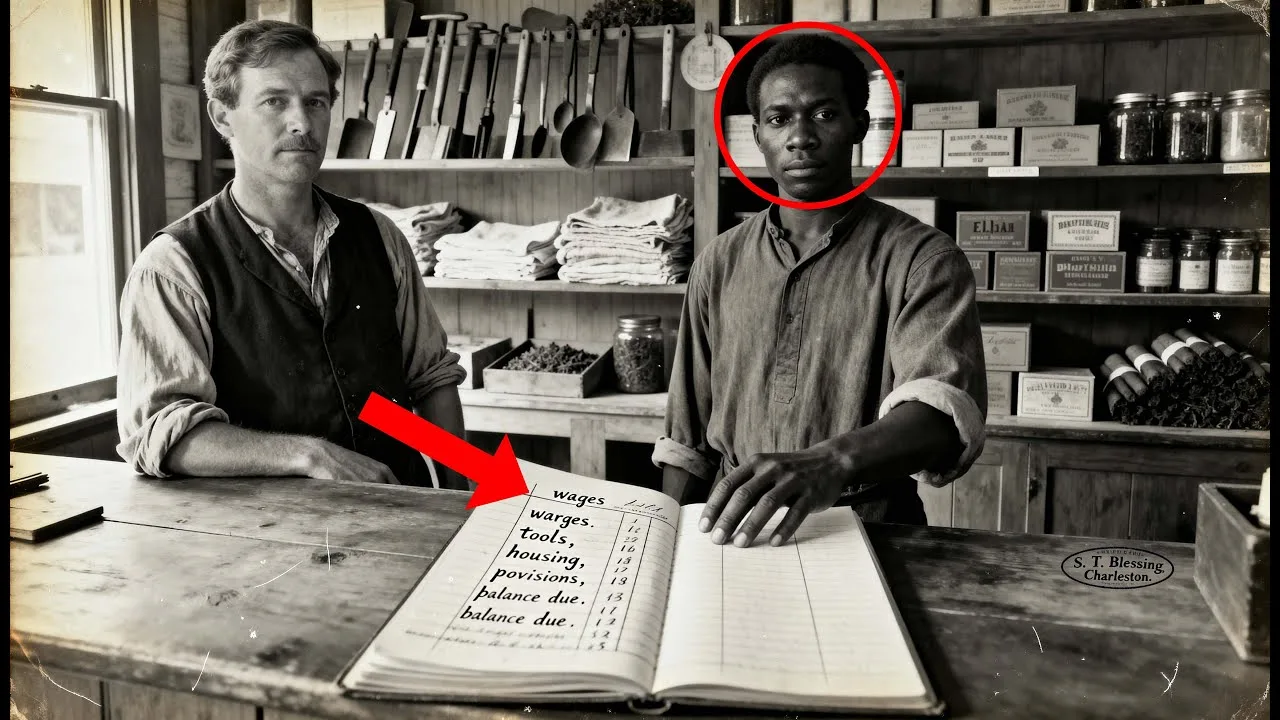

## Chapter 1: The Ledger Between Them

The image measured roughly four by six inches, printed on thick albumen paper.

In the foreground stood two men.

On the left, a white man in his fifties, sleeves rolled to the elbows, looked every bit the shopkeeper or merchant.

On the right, a Black man of similar age, neatly pressed work clothes, his posture careful and direct.

Both faced the camera.

Neither smiled, neither scowled.

They stood close, within arm’s reach, as if posed to suggest equality—or at least cooperation.

Behind them, shelves of goods rose toward a tin ceiling.

Between them, visible at waist height, sat an open ledger book on a wooden counter.

Dr.

Holt almost filed it away.

But something about the way the Black man’s hand rested on the counter drew her eye.

His fingers hovered just above the ledger’s open page, as if guarding it, or as if the photographer had asked him to point to it.

She reached for her magnifying glass.

The ledger’s pages were blurred but not illegible.

On one side, a column of numbers; on the other, words.

She made out fragments: “tools,” “housing,” “provisions.” At the bottom, a smaller entry: “balance due.” The amounts listed were substantial—twelve dollars for tools, eight monthly for housing, six for provisions.

The left side, where wages should have been, showed much smaller numbers.

The math didn’t add up.

Sarah set the photograph down and stared at it for a long moment.

This wasn’t just a pretty old photo.

Something was wrong.

## Chapter 2: The Clues in the Back

Turning the photograph over, Dr.

Holt found, in faded pencil, a name and date: “Elijah, 1868.” Nothing else—no surname, no indication of who the white man was or where the photograph had been taken.

But the handwriting matched other labels in the Rawlings collection, suggesting the photo had belonged to the family for generations.

The word “Elijah,” without a surname, carried its own weight.

In 1868, just three years after emancipation, formerly enslaved people were often recorded by first name only, their identities stripped of lineage markers that white families took for granted.

She pulled out a fresh pair of cotton gloves and lifted the photograph to the light.

The cardstock backing was warped, exposed to moisture.

In the lower left corner, she found a faint oval stamp.

The letters were worn, but she could make out part of a name: “St.

Blessing, Charleston”—a photographer’s mark.

That gave her a starting point.

## Chapter 3: The Photographer’s Intent

Samuel T.

Blessing operated a studio in Charleston between 1864 and 1881.

His work was well documented: Union soldiers, wealthy merchants, scenes of commerce and labor.

His prints survived better than most.

Dr.

Holt found Samuel’s name in city directories, advertisements in old newspapers, even a few surviving glass plate negatives in a university collection.

But no record of a photograph matching the one she held.

Many photographs from this period were privately commissioned and never cataloged.

What mattered was determining who had commissioned this one—and why.

The Rawlings family had no documented business interests in Charleston during Reconstruction.

Their holdings were concentrated in Georgetown County, where they’d owned a rice plantation before the war.

After emancipation, like many planter families, they shifted from enslaved labor to sharecropping and tenant farming.

But the photograph didn’t look like a plantation scene.

The shelves of goods, the counter, the ledger—all suggested a retail operation, a general store or supply depot.

## Chapter 4: The Debt Peonage System

Dr.

Holt reached out to Dr.

William Odum, a historian at the College of Charleston specializing in Reconstruction-era economic structures.

She sent him the high-resolution image and asked for his opinion.

His reply came the next morning, three paragraphs of controlled excitement.

“This is extraordinary,” he wrote.

“I believe you have found a photograph of a commissary store likely attached to a turpentine or lumber operation.

The ledger in the image appears to be an account book for what we would now call debt peonage.

If you look closely at the numbers, you will see that the charges listed far exceed any plausible wages.

This is not a portrait of cooperation.

It is a portrait of legal bondage.”

Debt peonage—the term sounded clinical, almost bureaucratic, but its reality was anything but.

After the Civil War, as the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery, Southern landowners and businessmen immediately began searching for legal workarounds.

They found one in labor contracts tied to debt.

A freedman would be offered work—often at a remote lumber camp, turpentine distillery, or plantation.

He could buy food, clothing, and tools on credit at the company store, with the cost deducted from his wages.

What he wouldn’t be told, at least not clearly, was that the prices at the store were inflated, the wages lower than expected, and the accounting controlled entirely by his employer.

Within weeks or months, he would owe more than he earned.

Under laws passed by Southern legislatures in the post-war years, a worker who left employment while in debt could be arrested, jailed, and returned to his employer by force.

It was slavery by another name—and it was perfectly legal.

## Chapter 5: The Ledger’s Lie

Dr.

Holt read Dr.

Odum’s email twice, then turned back to the photograph.

The two men, standing side by side, no longer looked like equals.

They looked like captor and captive, frozen in a pose designed to obscure the truth.

Elijah, whoever he was, stood beside the evidence of his own imprisonment, his hand resting just above the ledger that recorded his debt.

The question now was whether that evidence could still be found.

Dr.

Holt began tracing the Rawlings family’s post-war business activities.

Estate records, tax documents, and probate filings eventually led her to a name: Horus Rawlings, the second son of the plantation patriarch, had left Georgetown County in 1866 and established a turpentine operation in Colleton County, sixty miles inland from Charleston.

The operation was modest, employing twenty to forty workers to tap longleaf pines, collect resin, and distill it into turpentine and rosin for sale to northern merchants.

Workers lived in camps near the distillery, paid in a combination of cash and store credit.

Store credit—there it was.

Horus Rawlings died in 1892, his records passing through several generations before ending up in the donation box.

Most papers were routine.

But buried among them, Dr.

Holt found a thin bundle of ledger pages—water-stained and brittle—torn from a larger book.

The handwriting matched entries visible in the photograph.

The pages covered the years 1867 to 1869.

Each entry listed a worker by first name only, followed by columns for wages earned, store charges, and balance due.

The names were African-American: Elijah, Moses, Solomon, Delia, Patience, Caesar.

The pattern was the same in every case.

Wages credited were never enough to cover charges.

Balances grew month after month.

Beside each name, a notation appeared at irregular intervals: “Contracted,” followed by a date, or “Extended,” followed by a number of months.

Dr.

Holt showed the ledger pages to Dr.

Odum.

He confirmed what she suspected: “Contracted” meant the worker had signed or marked a labor agreement binding them to the operation until their debt was paid.

“Extended” meant the contract had been renewed, the debt refinanced, the term of service lengthened.

In theory, these were voluntary agreements.

In practice, they were inescapable.

A worker who tried to leave would be reported to local authorities, arrested under vagrancy laws, and either returned to the employer or leased out to another.

The choice was between legal bondage and imprisonment.

## Chapter 6: Elijah’s Account

Elijah appeared on several pages.

His entries showed charges for housing at eight dollars a month, provisions at six, tools and equipment at twelve to start, and then additional amounts for repairs and replacements.

His wages, listed separately, ranged from ten to fifteen dollars a month, depending on the season and the volume of resin collected.

The math was brutal.

Even in his best months, he fell further behind.

By the end of 1868—the year the photograph was taken—his balance due stood at over ninety dollars, a sum that would have taken years to repay at the rates offered.

But the ledger pages also contained something unexpected.

Beside Elijah’s entries, someone had made small marks in the margin—not numbers or letters, but symbols: a small circle, a diagonal line, a crude star.

They appeared inconsistently, sometimes beside charges, sometimes beside payments, sometimes in the gap between columns.

Dr.

Holt had no idea what they meant.

She photographed the pages and sent them to Dr.

Constance Frasier, a retired professor who had spent her career studying coded communication among enslaved and formerly enslaved communities in the South.

Dr.

Frasier called her back within hours.

“These are verification marks,” she said, “not made by the bookkeeper—made by someone else, someone who was checking the ledger’s accuracy.

This was a form of resistance.”

Workers in debt peonage systems often had no access to their own account records.

The employer controlled everything, but in some cases, literate members of the community—ministers, teachers, or fellow workers—would examine the books and note discrepancies.

The marks you are seeing are a record of that examination.

Someone was keeping track of the lies.

## Chapter 7: The Counter-Record

The photograph, which had seemed like a simple portrait of a freedman and his employer, was now something far more complex.

It was evidence of a system designed to re-enslave Black workers through debt.

And it was also evidence of resistance—someone within that system who had found a way to document the fraud, even if they could not stop it.

But who had made those marks? And what had happened to Elijah?

Dr.

Frasier mentioned that Black churches in the Low Country often served as centers of community recordkeeping during Reconstruction.

Many had been burned or scattered during the violence of the Redemption era, but a few had survived with their records intact.

She suggested Dr.

Holt contact the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor, an organization that preserves the history and traditions of African-American communities along the South Carolina and Georgia coast.

Through the corridor’s archival connections, Dr.

Holt located a small Baptist church in Colleton County, Mount Olive Baptist, founded in 1866 by freed men from local plantations and labor camps.

The church had experienced multiple burnings and rebuildings, but its earliest membership rolls survived, stored in a fireproof box.

The rolls listed names, dates of baptism, and brief notes about each member’s circumstances.

There, on the third page, Dr.

Holt found him: “Elijah, called Elijah Blessing after his former master, baptized August 1866, laborer at Rawlings Camp, known to read and cipher, appointed deacon 1867.”

Elijah could read and cipher.

In the context of a debt peonage system where workers were deliberately kept ignorant of their true accounts, that skill was dangerous.

The name Blessing was significant.

Many freed people took the surnames of former owners, but some chose names that reflected their new status or their hopes.

A man enslaved by someone named Blessing and then freed might take that name as a mark of irony or defiance.

## Chapter 8: The Photographer’s Connection

Samuel T.

Blessing, the photographer, had operated a portrait studio in Columbia before the war.

In 1858, he’d been commissioned to photograph the household of a wealthy merchant named Thaddeus Blessing—no relation, but possibly a distant cousin who owned several domestic workers.

One of those workers was listed as Elijah, age approximately twenty-five, house servant, literate.

Before the war, Elijah had been enslaved by a man named Blessing and trained as a literate house servant—a rare privilege that marked him as valuable property.

After emancipation, he took the Blessing name and eventually found his way to Horus Rawlings’s turpentine camp, where his ability to read made him both useful and threatening.

At some point, he was photographed by the very man whose relative had once owned him.

The photograph began to reveal its full meaning.

It was not a portrait of cooperation.

It was not even simply a portrait of exploitation.

It was a portrait of surveillance.

## Chapter 9: Evidence and Resistance

Horus Rawlings had brought Elijah to Charleston to Samuel Blessing’s studio to be photographed beside the ledger that recorded his debt.

The image was a document, a form of proof that the debt existed and that Elijah acknowledged it.

In an era before standardized contracts and legal enforcement, photographs like this served as evidence—a way for employers to demonstrate that their workers owed them money and were bound by that obligation.

But Elijah subverted the photograph’s purpose.

By resting his hand above the ledger, he drew attention to the very document meant to enslave him.

By quietly marking the margins of the real ledger back at the camp, he created a counter-record—evidence that the debts were fraudulent and that someone was watching.

## Chapter 10: What Happened to Elijah?

The Mount Olive Baptist Church rolls continued through 1876.

Elijah’s name appeared regularly until 1871 when a brief notation read, “Elijah Blessing removed to unknown location.

Pray for his safety.” The same year, Horus Rawlings filed a complaint with local authorities claiming several workers had fled without paying their debts.

Court records showed warrants were issued, but no record of capture or trial survived.

Dr.

Frasier had seen this pattern before.

When workers in these systems finally ran, they often headed north or west, following networks that resembled the old Underground Railroad.

Some made it, some were caught and returned.

Some disappeared into other labor systems where they were not known.

We may never learn Elijah’s fate, but the church’s prayer for his safety suggests they knew he was in danger—and they knew why.

## Chapter 11: The Decision to Reveal

With the photograph’s context now clear, Dr.

Holt faced a decision.

The Rawlings family had donated the collection with no restrictions, but exposing its contents would not be simple.

The Rawlings name still carried weight in the region.

Descendants served on museum boards, historical society committees, and local government.

The family cultivated an image of aristocratic grace and post-war adaptation, never mentioning the turpentine camp or its labor practices.

Revealing this photograph and its story would challenge that narrative directly.

She brought the matter to her supervisor, Dr.

Alan Prescott, the archives director.

He examined the photograph and ledger pages and then sat back with a long exhale.

“This is going to upset some people,” he said.

“The Rawlings Foundation has been a donor for fifteen years.

If we go public, we need to be ready for pushback.”

Dr.

Holt nodded.

“We have an obligation to the historical record.

And more importantly, we have an obligation to Elijah.

He was erased from his own story.

His resistance was forgotten.

If we sit on this, we are complicit in that erasure.”

## Chapter 12: The Exhibition and Its Impact

The archives advisory board debated for hours.

Some argued for caution, suggesting a private approach to the Rawlings family.

Others worried about legal liability.

A few questioned the interpretation.

But with written statements from Dr.

Odum and Dr.

Frasier, and the ledger entries clear, the board voted narrowly to proceed with a public exhibition.

Finding descendants of the workers named in the ledger was difficult but not impossible.

The Mount Olive Baptist Church still existed, its current pastor, Reverend Darnell Simmons, a genealogist in his own right.

He recognized some names immediately.

“Elijah Blessing,” he said slowly.

“There is a family by that name still in Walterboro.

They always said their ancestor was a hero, a man who stood up to the bosses after the war, but they never had details.

I think you just found them.”

Levvenia Blessing, a retired schoolteacher, agreed to speak with Dr.

Holt by phone.

She had never seen the photograph before, but she recognized the story.

“My grandmother used to say Elijah wrote things down.

He kept a secret book and when they found it, he had to run.

I always thought it was a family legend, but you’re telling me it was real.”

Dr.

Holt told her about the verification marks in the margins, the symbols identified as resistance.

Levvenia was quiet for a long time.

“He was fighting back,” she said finally.

“Even when they had him in chains, he was fighting back.

That’s who we come from.”

## Chapter 13: The Ledger’s Legacy

The exhibition opened in February 2021, nearly two years after Dr.

Holt first found the photograph.

It occupied a single gallery in the archives public wing and centered on one image—the 1868 portrait of Elijah and Horus Rawlings, enlarged and mounted on the main wall, with ledger entries and church records displayed below.

A video loop showed interviews with Dr.

Odum, Dr.

Frasier, and Levvenia Blessing explaining what the photograph revealed and why it mattered.

The title of the exhibition was “The Ledger’s Lie: Debt Peonage and Resistance in Reconstruction South Carolina.”

Attendance exceeded expectations.

Local newspapers covered the opening.

A journalist from a national magazine wrote a long piece on debt peonage, citing the photograph as a rare visual record of a system largely erased from public memory.

The Rawlings Foundation issued a brief statement acknowledging the historical record and expressing regret for their ancestor’s actions, though some family members privately complained that the archive had blindsided them.

But the most significant response came from the Blessing family.

Levvenia’s granddaughter, Cassandra, a recent law school graduate, visited the exhibition three times.

On her third visit, she asked to speak with Dr.

Holt.

“I’m going to write about this,” she said.

“Not just for my family, but for all the families whose ancestors were trapped in these systems.

The law school I attended never taught us about debt peonage.

Most people I know have never heard of it, but it didn’t end in 1870 or 1880.

It continued into the twentieth century.

My great-great-grandfather was not just a victim of Reconstruction.

He was a victim of something that lasted generations—and he fought it.

I want people to know that.”

Dr.

Holt handed her a folder with copies of all the documents, high-resolution scans of the photograph, the ledger pages, the church records, the research notes.

“Tell his story,” she said.

“Tell all their stories.”

## Chapter 14: What Photographs Hide

The photograph of Elijah and Horus Rawlings now hangs in the permanent collection.

Its label has been rewritten twice since the exhibition, each time adding more context as researchers uncover new details.

The most recent version includes a sentence Dr.

Holt wrote herself: “This image was designed to document a debt.

It now documents a resistance.”

But the story does not end with one photograph.

Debt peonage was not unique to Colleton County or the turpentine industry.

It flourished across the South for decades after emancipation, trapping hundreds of thousands of Black workers in conditions nearly indistinguishable from slavery.

It operated through sharecropping, convict leasing, and company stores.

It was enforced by local sheriffs, justified by vagrancy laws, and ignored by federal authorities who had lost interest in protecting the freed people they had once liberated.

It did not end until well into the twentieth century, and its effects shaped patterns of poverty and migration that persist today.

The photographs of that era—the images that fill archives and family albums and museum collections—are full of ledgers, account books, contracts, and tools of control that we have trained ourselves not to see.

A portrait of a prosperous merchant and his “loyal employees” might hide the same exploitation that Elijah endured.

A photograph of a happy family in front of a general store might conceal generations of unpaid labor.

The camera recorded what was staged, but the staging itself was a form of erasure.

Dr.

Holt has since examined dozens of similar images, looking for the same patterns: a ledger open at an odd angle, hands positioned near account books, workers posed beside the tools of their own bondage.

In many cases, she finds nothing.

But in some, she finds the same story—charges that exceed wages, contracts renewed without consent, debts that could never be paid.

She has also found more verification marks, marginal symbols scratched into ledger pages by unknown hands—small acts of defiance in a system designed to crush resistance.

Each one is a reminder that the people in these photographs were not passive victims.

They were strategists, recordkeepers, witnesses to their own oppression.

They left evidence for anyone willing to look.

## Seeing What Was Meant to Be Hidden

The next time you see an old photograph in a museum or textbook, look at it carefully.

Look at the hands.

Look at what they hold or touch or point toward.

Look at the objects in the background—the papers, ledgers, and contracts that frame the scene.

Ask what the image was meant to say, and what it might be hiding.

Because somewhere in that frame, if you know how to look, you might find a story that was never meant to be told.

And you might find someone who was waiting across all those years to finally be seen.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load