A Photograph Hidden in Dust and Time

The attic smelled of dust and forgotten time—a scent that clung to every artifact Sarah Mitchell unearthed in the abandoned plantation house outside Baton Rouge.

As a documentary researcher from New Orleans, Sarah had spent months cataloging relics from post–Civil War Louisiana families.

But this day, her flashlight caught something different: a tarnished silver frame wedged between two leatherbound journals.

Inside was a photograph, dated April 1867, from Bulmont Studio in New Orleans.

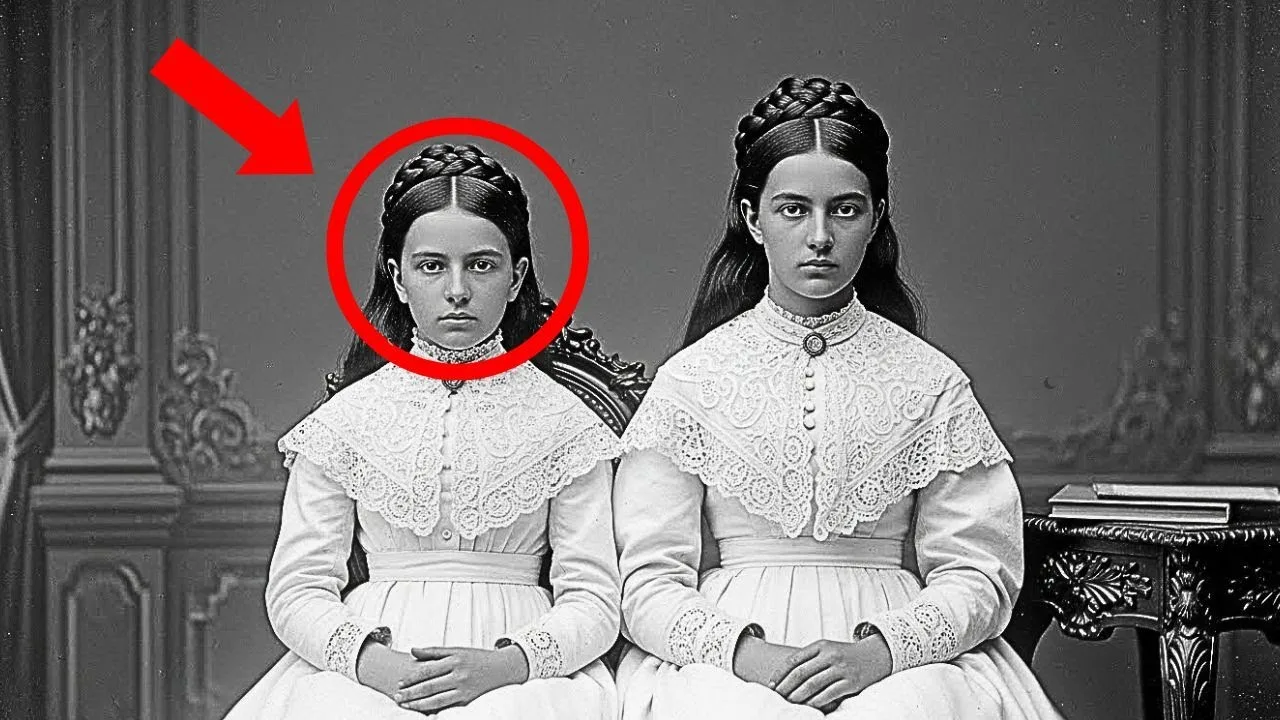

Two girls, perhaps twelve and fourteen, sat side by side in an elegant studio setting.

They wore identical white dresses with lace collars and elaborate braids.

Their faces were solemn, their eyes intense—the same jawline, the same nose, the same gaze.

Sisters, clearly.

But what Sarah didn’t yet know was that this portrait hid a secret that would challenge everything she thought she knew about family, race, and courage in the Reconstruction South.

## Chapter 1: The Discovery

Sarah snapped a photo and sent it to Marcus, a genealogist specializing in Louisiana families.

Within an hour, Marcus called, his voice tight with excitement.

“Do you know whose house this was?”

“The Bowmont estate,” Sarah replied.

“Thomas Bowmont owned it before the war.

Cotton and sugar.”

“I found records,” Marcus said.

“Thomas Bowmont died in 1866.

He had one legitimate daughter, Catherine.

But there’s a freed slave registry from 1865.

A woman named Eliza was freed from the Bowmont plantation, along with a daughter named Marie born in 1853.”

Sarah stared at the photograph.

Catherine and Marie—two sisters, one free, one enslaved until the end of the war.

This portrait, taken two years after emancipation, showed them dressed identically, posed as equals.

“That shouldn’t exist in 1867 Louisiana,” Marcus said.

“Not like this.

Not so openly.”

Sarah removed the photograph from its frame.

On the back, beneath the date, were words she hadn’t noticed before, written in a different hand: “Forgive us for what comes next.”

Her hands trembled as she read those words again.

## Chapter 2: The Bowmont Family’s Secret

Sarah and Marcus spent days immersed in parish records, cemetery logs, and archived newspapers.

Thomas Bowmont had inherited the plantation in 1840, married Virginia from a prominent New Orleans family in 1842, and fathered Catherine in 1851.

Marie was born in 1853 to Eliza, listed as property of the Bowmont household.

But what was unusual was what happened after Thomas died.

Most plantation owners’ wills divided property among white heirs; former slaves were ignored.

But Thomas’s will was sealed by the court.

Marcus requested access, but it would take weeks.

“What about Virginia?” Sarah asked.

“His wife?”

Marcus slid a newspaper clipping across the table.

The New Orleans Daily Picayune, June 1867: “Widow Bowmont withdraws from society.” Virginia had ceased attending social functions and closed the plantation house to visitors.

Neighbors speculated about illness or grief, but no explanation was given.

“Two months after that photograph was taken,” Sarah murmured.

She studied the girls’ faces under the library’s harsh lights.

Catherine sat with perfect posture, hands folded.

Marie mirrored her position, but her eyes looked different—not defiant, but watchful, as if she expected the world to snatch this moment away.

“There’s something else,” Marcus said.

“Eliza’s death record.

She died in April 1867—the same month as the photograph.”

Sarah’s breath caught.

“How did she die?”

“It doesn’t say.

Just ‘natural causes.’ But she was only thirty-two.”

## Chapter 3: The Studio Ledger

Sarah tracked down the Bowmont Studio building on Royal Street, now a coffee shop.

The owner, Diane, led her to the basement, where boxes of old papers waited.

Sarah found the ledger from 1867.

April 14th, 1867: “Bowmont, Virginia.

Portrait, two subjects, full studio setup.

Payment $25.”

$25 was a fortune for a photograph in 1867—months of wages for most workers.

This was something carefully planned.

Sarah called Marcus.

“Virginia commissioned the photograph herself.

She paid a fortune for it.”

“So she wanted this photograph taken,” Marcus said.

“After her husband died, after Eliza died, she brought both girls to the studio and had them photographed as equals.

But why?”

Diane spoke up.

“There’s something written on the inside cover of that ledger.”

Sarah turned to the front.

In faded pencil: “Some debts cannot be paid with money.

Some truths cannot be buried.” Signed, Charles Bowmont, photographer.

## Chapter 4: Letters from the Past

Back at the plantation, Sarah searched for more evidence.

Hidden beneath a stack of tablecloths, she found a small leather case tied with blue ribbon—dozens of letters.

The first, March 1867:

> My dearest Catherine, you are old enough now to understand the truth, though it pains me to write these words.

Your father was not a perfect man.

He made choices I cannot defend, but I can try to set right.

Marie is your sister in every way that matters—in blood, in circumstance, in the loss you both have suffered.

When I am gone, you must remember what I am about to do.

You must remember that I chose love over propriety, truth over comfort.

> Your mother, Virginia.

This wasn’t just a photograph.

It was a declaration.

Other letters spoke of Virginia’s determination to raise both girls together, to give Marie the same education and opportunities as Catherine, to acknowledge publicly what society demanded she hide.

One letter, March 28th, 1867, from Margaret, a childhood friend:

> You have lost your senses.

That girl is not your daughter.

She is the child of sin, the product of your husband’s weakness.

To claim her as Catherine’s equal will destroy your reputation, Catherine’s future, and any hope of maintaining your position.

Send her away.

Virginia’s response, paperclipped to the letter:

> Dear Margaret, my husband’s weakness does not diminish Marie’s humanity.

My reputation means nothing if I cannot sleep at night.

I have made my decision.

Please do not write again.

> Virginia.

## Chapter 5: The Will That Changed Everything

Marcus arrived with Thomas Bowmont’s will.

Its contents were extraordinary: the estate divided into three equal parts—one-third to Virginia, one-third to Catherine, one-third to Marie, whom he identified as his daughter by Eliza.

Thomas had written a letter to be opened after his death:

> I have lived as a coward, unable to claim publicly what I know in my heart.

Marie is my daughter as surely as Catherine is.

Eliza was not my property, but the woman I loved, though the law forbade me from honoring that love openly.

I beg forgiveness for the pain I have caused, and I beg my daughters’ forgiveness for the world I am leaving them to navigate.

May Virginia have the strength I lack to do what is right.

Virginia read this after he died and decided to honor it—bringing both girls into her home, dressing them as equals, having them photographed as sisters.

It was a statement to society, to family, to history.

## Chapter 6: Aftermath and Resistance

But what happened to them?

A property deed from 1869 showed a house in New Orleans purchased jointly by Catherine and Marie—no last names, just first names.

Society pages referred to them obliquely as “the Bowmont sisters, the young ladies of Magazine Street.” Never photographed again, never named directly.

Society knew they existed but refused to acknowledge them.

Sarah dug deeper into Eliza’s story.

Born in 1835, sold to Thomas Bowmont in 1850, she worked in the main house.

Church records revealed her love for Marie and her fear for her daughter’s future.

In early 1867, Eliza grew weaker, her heart failing.

Her last words, recorded by the pastor: “Tell Marie to be brave.

Tell her she is loved.

Tell her she is free.”

Four days after Eliza’s death, Virginia took both girls to the studio.

The photograph wasn’t just a portrait—it was a promise kept.

## Chapter 7: Society’s Backlash

Sarah read through newspapers and private journals.

In May 1867, the New Orleans Ladies Social Guild declared Virginia Bowmont “no longer in good standing.” Letters between families decried Virginia’s “scandal,” predicting Catherine would never find a suitable husband.

But there were other voices.

An editorial in a progressive newspaper praised Virginia’s “Christian charity and moral courage.” Court records showed relatives tried to have Virginia declared mentally incompetent; the case was dismissed when doctors testified to her soundness of mind.

She fought for her daughters every step of the way, liquidating the plantation and most business holdings to maintain independence.

## Chapter 8: Catherine and Marie—A Life Together

In a trunk, Sarah found Catherine’s journal, beginning in 1868.

> January 4th, 1868: Marie and I walked in the garden today.

People stared, but we held our heads high as mother taught us.

Marie asked if I resent her for what we’ve lost.

I told her I only resent those who cannot see what mother sees.

> March 12th, 1868: A woman spat at mother in the market.

Marie tried to step between them.

That evening, mother said, “You will face worse than this.

People will try to convince you your bond is shameful.

Do not listen.

You are sisters, and that truth is worth more than all their approval.”

> July 20th, 1868: Marie’s birthday.

She cried for her mother.

I held her and thought about how strange it is that we share a father but grew up in such different worlds.

She told me stories about Eliza—how she sang, taught her to read in secret, always told Marie she was destined for more than servitude.

> Late 1868: Marie asked what will happen when mother dies.

I took her hands and said, “You are my sister.

Where I go, you go.

If society will not accept us both, then society can watch us walk away together.”

Marcus made a breakthrough: After Virginia died in 1873, the sisters moved to Philadelphia, changed their last name to Lawrence.

Catherine became a teacher, founding a school for girls—white and black students alike.

Marie became an artist, exhibiting her work and selling paintings.

In 1880, her painting “Sisters” depicted two young women in white dresses, seated side by side—challenging viewers’ prejudices.

They lived together their entire lives.

When Catherine died in 1901, she left everything to Marie.

When Marie died in 1909, her will established a scholarship fund for young black women pursuing education or the arts—a fund that still exists today.

## Chapter 9: Legacy and Remembrance

Sarah stood in the Louisiana Historical Society’s exhibition hall, the portrait of Catherine and Marie restored and lit to show every detail.

Beside it were Virginia’s letters, Catherine’s journal, and documents about Eliza’s life.

The exhibition, The Portrait of Silence: How Three Women Defied the Post-War South, drew researchers, descendants, and visitors who needed to see evidence that love and courage could prevail over prejudice.

A young black woman approached Sarah, tears streaming down her face.

“My grandmother told me stories about a relative who lived with a white woman in the 1800s—a school in Philadelphia, a woman who painted.

I think Marie might be my ancestor.”

Two months later, DNA tests confirmed the connection.

Marie’s great-great-great-great-granddaughter stood in the exhibition hall, looking at the photograph.

“They survived,” she said softly.

“Despite everything, they survived and built something beautiful.”

Sarah thought about the words on the back of the photograph: “Forgive us for what comes next.” Virginia had known her decision would bring hardship, discrimination, and social exile.

She was asking forgiveness not for the choice, but for the burden it placed on her daughters.

But Catherine and Marie transformed that burden into purpose, building a life that honored everyone who had sacrificed for them.

## A Testament to Love, Courage, and Defiance

The exhibition became one of the historical society’s most visited, drawing descendants and people who needed proof that family could be chosen, defended, and celebrated even when the world insisted otherwise.

Sarah often returned to stand before the portrait, studying the faces of two girls who refused to let society’s limitations define them.

In their solemn expressions, she saw not resignation, but quiet determination—a promise kept, a vow made visible, and a legacy that endures.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load