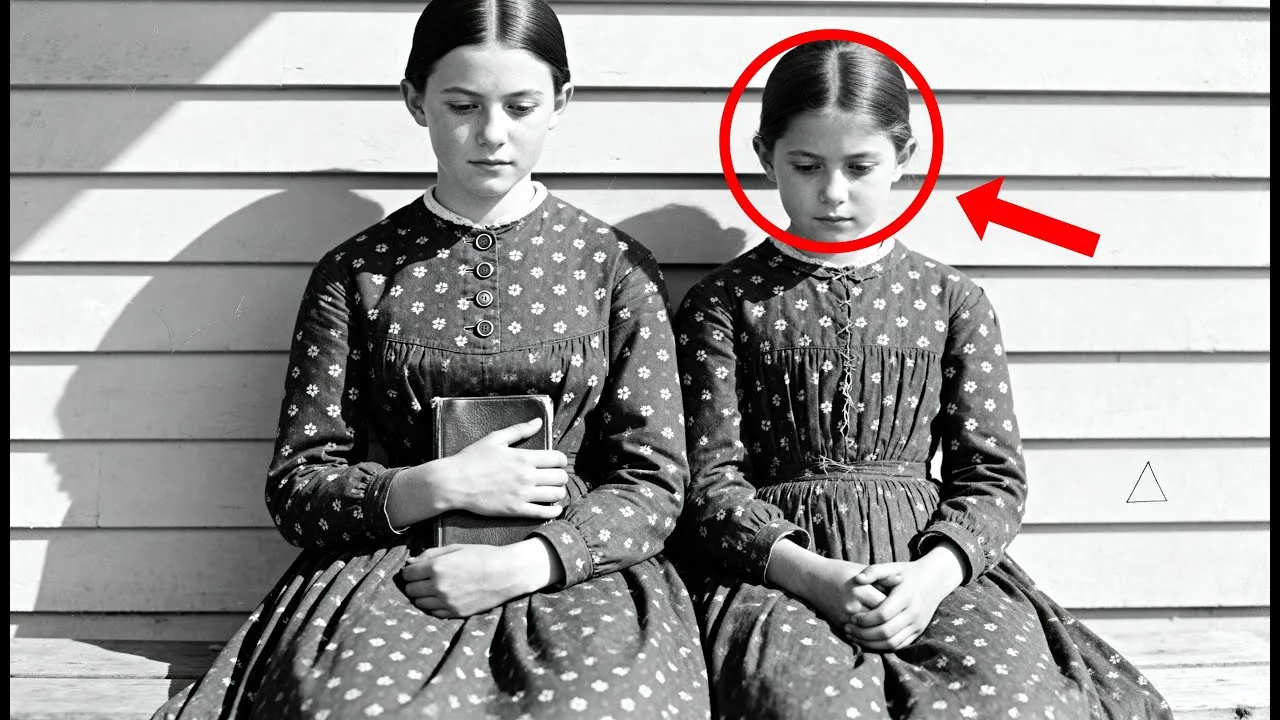

This 1862 photograph of two sisters appears peaceful until you notice the missing button.

It seemed like nothing at first, just another Civil War era portrait from a border state worn at the edges but carefully preserved until Dr.

Rebecca Harding, a textile historian at a small college in Maryland, realized the missing button was not an accident.

She found the photograph in a cardboard box at an estate sale 3 mi from the West Virginia line.

The house had belonged to the last descendant of a farming family named Cassell, and most of the items inside were being cleared out by a realtor who seemed relieved to let anyone haul away the dusty collections filling the attic.

Rebecca went for the quilts and samplers.

She stayed for the photographs.

The image showed two girls on a wooden porch.

The older one looked about 12, the younger maybe eight.

Both wore homemade cotton dresses in a matching pattern, dark fabric with tiny white flowers.

Their hair was parted down the middle and pulled back severely, the style of respectable households during the war years.

The older girl held a small leather-bound book in her lap, her hand resting on the cover.

The younger girl sat with her hands folded.

Behind them, the porch railing cast shadows across clabbered sighting.

Everything looked orderly, domestic, frozen in the amber of early photography, except for the collar.

Rebecca brought the photograph closer to the window light.

The older girl’s collar was fastened at the throat with three buttons, but the fourth button hole, just below the others, gaped open.

The thread loop that should have held a button was stretched and frayed, pulled long, as if something had been yanked away recently.

The fabric around it puckered slightly.

Every other part of both dresses was immaculate, hems, even seams straight, collars pressed.

The missing button stood out like a word scratched from a letter.

Rebecca turned the photograph over on the back in pencil.

E and M.

Cassell, June 1862, Harper’s Ferry Road.

This was not just a pretty old photo.

Something here was wrong.

Rebecca Harding had spent 15 years studying 19th century textiles in domestic material culture.

She had examined hundreds of period garments in museum storage, cataloged quilt patterns from Appalachian households, and written two books on the sewing practices of rural women during the Civil War.

She knew how much labor went into a homemade dress in 1862.

Spinning, weaving, cutting, stitching.

Buttons were expensive, often made from bone or wood, sometimes covered in matching fabric.

You did not lose one casually, and if you did, you replaced it before sitting for a formal photograph.

Formal photographs cost money.

A traveling photographer with a portable dark room would have charged the family a significant sum.

You prepared for that moment.

You mended, pressed, arranged.

You did not sit for your portrait with your collar undone.

Rebecca carried the photograph to her office and placed it under her desk lamp.

She pulled out a jeweler’s loop and studied the surface grain.

The image had been printed on albumin paper, a common process for the era, and mounted on thick cardboard.

The cardboard backing was embossed with a stamp in faded gold ink.

Jay Whitmore, traveling portraiture, Shannondoa Valley.

She made a note of the name.

She examined the girl’s faces next.

The older one looked directly at the camera with an expression that was hard to read, not quite solemn, not quite defiant.

The younger girl seemed more nervous, her eyes slightly unfocused, as if she had been told to sit still and was concentrating hard on doing so.

Rebecca checked their hands.

No rings, no jewelry.

The book in the older girl’s lap had no visible title on the spine.

Then she turned the photograph over again and looked more carefully at the pencil inscription.

The handwriting was neat, feminine, probably written by an adult woman sometime after the image was taken.

But there was something else.

A tiny mark in the lower right corner, almost invisible unless you held the card at an angle.

Three short scratches in the shape of a crude triangle.

Rebecca sat back.

She had seen marks like that before in her research on underground railroad quilts and signal systems.

Abolitionists and those who aided escaping enslaved people sometimes used geometric symbols to communicate.

A triangle could mean safe house or forward or caution.

But that research was contested, full of folklore and wishful thinking.

Most historians agreed that the famous quilt codes were likely invented long after the war.

Still, it was documented that some families did use visual markers, especially in border regions where neighbors spied on neighbor and union and confederate sympathies tangled like roots.

She felt the familiar pull of a story demanding to be told.

If she ignored this, if she sold the photograph to a collector or donated it to an archive without asking questions, something real would stay buried.

She opened her laptop and began searching for information on the Cassell family and Jay Whitmore, the photographer.

The first records came quickly.

The 1860 census listed a family named Cassell in Jefferson County, Virginia, near the Harper’s Ferry Road.

The household included Daniel Cassell, age 41, farmer, his wife Lydia, a 38, two daughters, Elizabeth, a 10, and Mary, age 6.

The ages match the girls in the photograph taken 2 years later.

The family owned 80 acres and no enslaved people, which was unusual but not unheard of in that part of Virginia.

Many small farmers in the border counties worked their own land.

Rebecca searched newspaper archives next.

She found a brief mention of Jay Whitmore in an 1863 issue of a Martinsburg paper.

He had placed an advertisement offering dgeraype and ambertype likenesses, guaranteed permanence, sittings taken in your home or place of business.

The ad ran for 3 weeks and then stopped.

She found no other references to him.

She contacted a colleague, Dr.

Marcus Trent, who taught Civil War history at a university in Virginia.

She sent him a scan of the photograph and asked if he knew anything about Jefferson County during 1862.

He called her 2 days later.

“That area was a nightmare,” Marcus said.

“You had Union troops moving through, Confederate cavalry raiding, local militias that switched sides depending on the week.

Harper’s Ferry changed hands eight times during the war.

Families were split.

If you were a union sympathizer in Virginia, you kept quiet or you got burned out.

What about people helping fugitive slaves? Rebecca asked.

Definitely.

There were active networks all through the Shannondoa Valley and up into Pennsylvania, but it was incredibly dangerous.

Virginia had slave patrols, and after John Brown’s raid in 1859, the state cracked down hard.

If you were caught harboring a runaway, you could be hanged or lynched before you even got a trial.

Rebecca told him about the missing button and the triangle mark on the back of the photograph.

Marcus was quiet for a moment.

You think the button meant something? I think it might have.

There were signal systems, he said slowly.

We know that for sure.

Lanterns in windows, markings on fence posts, certain flowers planted by the door.

The specifics are hard to verify because people did not write it down for obvious reasons.

But yeah, clothing could be part of it.

A bonnet hung on a porch rail, a colored ribbon on a gate post, something that looked normal but carried a message.

Rebecca asked if he knew any specialists in Underground Railroad history for that region.

He gave her the name of a woman in Harper’s Ferry, Dr.

Nora Chen, who worked with the National Park Service and had published extensively on resistance networks in the borderlands.

Rebecca drove to Harper’s Ferry the following week.

The town clung to the steep hillsides where the PTOIC and Shannondoa rivers met, a geography that had made it strategically vital during the war and a natural crossroads for people moving north.

Dr.

Chen met her at the park archives, a low brick building near the old armory site.

Rebecca showed her the photograph and explained what she had found so far.

Dr.

Chen studied the image carefully, then pulled out a folder from a filing cabinet.

There are fragmentaryary records, she said, laying papers on the table between them.

Diaries, letters, coded references in abolitionist newspapers.

After the war, some people gave testimonies to Freriedman’s bureau agents or to church groups trying to document what had happened.

A lot of it was destroyed or lost, but some survived.

She opened a yellowed notebook.

This is a transcript of an interview conducted in 1868 with a woman named Harriet Cole.

She had been enslaved in Jefferson County and escaped in 1862.

She made it to Pennsylvania and later gave this account to a Quaker relief organization.

She talks about a family that helped her.

No last name given, just a first initial, L, and her daughters.

They lived on the Harper’s Ferry Road.

Rebecca felt her pulse quicken.

Lydia Cassell.

The mother’s name was Lydia.

Dr.

Chen nodded.

It fits.

Harriet describes being hidden in a root cellar for two days while Confederate cavalry searched the area.

She says the daughters brought her food and that one of them had been taught a signal to use if strangers came to the door.

She doesn’t say what the signal was, but she mentions that the family took enormous risks and that other people in the network knew how to recognize their home.

How would they recognize it? She does not specify, but there are other accounts from the region that mention visual markers, a specific number of fence pickets painted white.

A birdhouse hung at a certain height.

One man who escaped through Maryland in 1863 said he was told to look for a house where a woman wore a blue shawl on Tuesdays.

These things sound folkloruric now, but they made sense at the time.

You needed a way to identify a safe house without knocking on the wrong door and getting everyone killed.

Rebecca showed Dr.

Dr.

Chen, the missing button and the stretched thread loop.

Could a button have been part of that? Dr.

Chen leaned closer, examining the photograph under a magnifying lamp.

It is possible.

Think about it.

You are a conductor on the Underground Railroad.

You need to tell people, “Go to the house on the Harper’s Ferry Road, the one where the woman’s collar is missing the fourth button.” Specific enough to identify, subtle enough that soldiers riding past would not notice.

And if you needed to signal that the house was unsafe, you sewed the button back on.

But this is a photograph, Rebecca said.

Why would they sit for a portrait with the signal visible? Maybe they did not realize the photographer would capture it.

Or maybe, Dr.

Chen said slowly, this photograph was meant to be documentation, proof of who they were.

There are accounts of abolitionists creating records for themselves, things they hid away in case they needed to prove their actions later or in case they died and someone needed to know what they had done.

Rebecca felt the weight of that, a photograph as testimony, as evidence, as defiance.

Dr.

Chen pulled out another document, a letter from 1865 written by a Union chaplain who had worked in the Shannondoa Valley.

He described meeting families after the war who had aided fugitive slaves and who were now facing retaliation from Confederate sympathizers in the community.

Some had lost their homes, some had been threatened, the chaplain wrote.

They ask only that their actions not be forgotten, though they understand that public acknowledgement could still endanger them.

Rebecca returned to Maryland with copies of the documents.

She spent the next 3 weeks tracing every reference she could find to the Cassell family.

County deed records showed that Daniel Cassell had purchased his farm in 1851 from a larger estate that was being divided.

Tax records confirmed he owned no enslaved people in 1860 or 1862, which would have made him part of a small minority of white farmers in that area.

A church membership role from a Methodist congregation in Shepherd’s Town listed Lydia Castle and her daughters, though Daniel’s name did not appear.

That suggested a possible rift.

or that Daniel attended elsewhere or no longer attended at all.

Then she found the letter.

It was filed in the Virginia Historical Society’s collections, part of a batch of Civil War correspondents that had been donated in the 1920s.

The letter was dated August 1862, 2 months after the photograph was taken.

It was written by a Confederate major named Thomas Grayson to his wife.

Most of the letter dealt with troop movements and mundane requests for supplies.

But near the end, Grayson wrote, “We searched the Cassell property again yesterday on suspicion of harboring fugitives.

Found nothing, but the woman has the look of a fanatic, and I would not trust her word.

The daughters are young, but already infected with abolitionist sentiment.

I have warned the neighbors to watch them closely.” Rebecca stared at the page.

The woman has the look of a fanatic.

She thought of Lydia Cassell sitting in her farmhouse in the summer of 1862.

Confederate troops searching her root cellar, her daughters upstairs trying to stay quiet.

She thought of Elizabeth and Mary, 10 and 8 years old, learning to lie convincingly to men with guns.

She contacted Marcus Trent again and asked if he knew of any other records related to Confederate searches or arrests of civilians in Jefferson County.

He pointed her to a collection of military correspondents held by the Library of Virginia.

Rebecca traveled to Richmond and spent two days combing through brittle folders of letters, reports, and lists.

She found Daniel Cassell’s name in a list dated November 8 to 1862.

He had been arrested on suspicion of giving aid and intelligence to the enemy.

The record indicated he was held for 3 weeks and then released without charges, though his property was confiscated temporarily.

Another note scrolled in the margin by a different hand read, “Wife and children remain under observation.” Rebecca pieced together what that meant.

Daniel had been arrested, likely as a warning.

The family had been marked as suspect.

And yet, according to Harriet Cole’s testimony, Lydia continued to hide fugitive slaves even after her husband’s arrest.

Either Daniel had been released and decided the risk was worth continuing, or Lydia had kept going on her own.

Rebecca found no record of Daniel Cassell after 1863.

His name disappeared from tax roles and deed transfers.

She found a death notice in a Martinsburg newspaper from April 1864.

Daniel Cassell, farmer, age 45, killed by bushwhackers on the road near Shephardd’s Town.

Bushwhackers was a euphemism for a regular Confederate forces or local vigilantes.

The notice gave no other details.

She did find Lydia in the 1870 census.

Lydia Cassell, now listed as widowed, was living in Pennsylvania with her two daughters, both in their late teens.

She worked as a seamstress.

The family had left Virginia.

Rebecca now understood the system the photograph documented.

The Cassell family had been part of a network of union sympathizers and abolitionists operating in one of the most dangerous places in the country.

They had used visual signals to communicate with conductors and fugitive slaves.

The missing button was not a wardrobe malfunction.

It was a marker, a message, a declaration frozen in albammen and light.

But what Rebecca did not yet know was what had happened to the photograph itself.

Why had it survived? Who had kept it? And why had it ended up in an attic in Maryland, miles from where the Cassels had lived? She went back to the estate sale and tracked down the realtor, a tired looking man named Paul Greg, who seemed annoyed to be interrupted.

She asked him about the family who had owned the house.

Last one died 2 years ago, he said.

Helen Marsh.

No kids, no close relatives.

Everything went to a cousin in Ohio who just wanted it cleared out.

Do you know if Helen Marsh was related to the Cassels? Paul shrugged.

No idea.

There was a lot of old junk in that attic.

Letters, photo albums, things from all over.

Could have been her family.

Could have been stuff she bought at other estate sales.

People collect things.

Rebecca asked if there were any other papers or documents from the attic that had not been sold yet.

Paul led her to a storage unit on the edge of town and unlocked a container filled with cardboard boxes.

“Help yourself,” he said.

“Anything you do not take is going to the dump next week.” Rebecca spent 4 hours going through the boxes.

Most of it was mundane.

Receipts, church bulletins, expired insurance policies.

But in the bottom of the fifth box, she found a bundle of letters tied with string.

They were addressed to Helen Marsh at various addresses in Maryland and Pennsylvania.

One envelope, postmarked 1953, had a return address in Harrisburg.

The sender’s name was Elizabeth Cassell Hughes.

Rebecca opened the letter carefully.

The handwriting was shaky but clear.

Dear Helen, thank you for your kind note about mother’s passing.

It has been a difficult year.

I am enclosing the photograph you asked about.

I think you should have it.

You understood what it meant to her and what it cost.

The button was the signal.

Mother wore that dress for years after the war, always with the fourth button missing.

She said it was a reminder that some things should never be hidden.

I am too old now to be the keeper of these stories, but I trust you will know what to do.

Yours in friendship, Elizabeth.

Rebecca sat on the concrete floor of the storage unit holding the letter.

Elizabeth Cassell, the older girl in the photograph, had lived into her 90s.

She had kept the photograph and eventually given it to a friend, someone who understood its significance.

And that friend, Helen Marsh, had kept it in her attic until she died.

Rebecca photographed every page of every letter in the bundle.

Then she returned to her office and began drafting a proposal.

She wanted to mount an exhibition about the Cassell family and the photograph.

She wanted to tell the story of Lydia and her daughters, of the risks they had taken, of the people they had saved.

But she knew that would not be simple.

The college where Rebecca taught had a small gallery space that hosted rotating exhibitions, mostly faculty projects, and student work.

The gallery was overseen by a committee that included the dean of humanities, two senior professors, and a representative from the college’s board of trustees.

Rebecca submitted her proposal in October along with highresolution scans of the photograph and excerpts from the documents she had gathered.

The committee met in November.

Rebecca was invited to present her findings.

She stood in a conference room with the photograph projected on a screen and walked through the evidence.

The missing button, the Confederate major’s letter, Harriet Cole’s testimony, Elizabeth Cassell’s note to Helen Marsh.

She explained the system of visual signals used by underground railroad networks and the specific dangers faced by Union sympathizers in border regions during the Civil War.

When she finished, the room was quiet.

Then Dr.

Andrew Winters, a history professor who had been at the college for 30 years, spoke.

“This is compelling research,” he said.

“But I have concerns about how we frame it.

You are making significant claims based on fragmentaryary evidence.

A missing button, a cryptic mark on the back of a photograph, a letter written 90 years after the events in question.

How do we know Elizabeth Cassell’s memory was accurate? How do we know the button was not simply lost? Rebecca had expected this.

We cannot know with absolute certainty, she said.

But the convergence of evidence is strong.

The Cassell family was documented as being under Confederate suspicion.

Harriet Cole’s testimony places a family matching their description on the Underground Railroad.

The letter from Elizabeth explicitly states that the button was a signal and the fact that Lydia continued to wear the dress with the button missing after the war suggests it held symbolic meaning for her.

Symbolic meaning is not the same as historical fact.

Winter said, “We have to be careful about projecting narratives onto images, especially when those narratives fit contemporary political sensibilities.” The dean, a woman named Dr.

Patricia Thornton, leaned forward.

“What concerns me is the potential controversy.

If we mount an exhibition making these claims, we are going to attract attention.

Some of it will be positive, some of it will not.

We will have people questioning our scholarship, accusing us of activism disguised as history.

And we will have donors who may not appreciate the college taking what they perceive as a political stance.

This is not a political stance, Rebecca said.

This is history.

The Underground Railroad existed.

People in border states risk their lives to help enslaved people escape.

That is documented fact.

This photograph gives us a rare glimpse of how one family participated in that network.

We should tell that story.

But how do we tell it? Patricia asked.

Do we present it as definitive truth or as a probable interpretation? Do we include desending views? Do we acknowledge the gaps in the evidence? We can do all of that, Rebecca said.

We can frame it as an investigation.

We can show the process of research, the documents, the questions that remain, but we cannot pretend the evidence does not point in a clear direction.

The board representative, a man named Richard Cole, who ran a local insurance company, cleared his throat.

I think we need to consider the reputation of the college.

We are a small institution.

We rely on community support and alumni donations.

If we become known as a place that pushes controversial interpretations of history, that could have consequences.

Rebecca felt her frustration rising.

With respect, telling the truth about the past is not controversial.

What is controversial is choosing to ignore evidence because it makes people uncomfortable.

I’m not suggesting we ignore anything, Richard said.

I’m suggesting we proceed carefully.

The committee decided to table the decision and revisit it in a month.

Rebecca left the meeting feeling deflated.

She called Marcus Trent and told him what had happened.

They are worried about donor money.

Marcus said that is what this is really about.

There are still people who do not like being reminded that their ancestors were on the wrong side of history or that some white people actively resisted slavery.

It complicates the narrative.

So what do I do? You document everything.

You publish the research.

Even if they do not give you the exhibition, you make sure the story gets out there one way or another.

Rebecca spent the next month doing exactly that.

She wrote a detailed article for a journal on material culture and civil war history laying out all the evidence and her interpretation of the photograph.

She submitted it and waited.

While the article was under review, she also contacted a filmmaker she knew, a documentarian who specialized in forgotten histories.

She shared the story of the castle family and the photograph.

The filmmaker was interested.

In December, the committee met again.

This time, Patricia Thornton called Rebecca beforehand.

We have decided to approve the exhibition, she said, but with conditions.

We want prominent disclaimers acknowledging that some elements are interpretive.

We want input from other historians, including dissenting opinions, if they exist, and we want to be very careful about how we market it.

No sensational language, no claims we cannot fully back up.

Rebecca agreed.

It was not everything she had hoped for, but it was enough.

The exhibition opened in March.

It was small, just one room, but Rebecca designed it carefully.

The photograph of Elizabeth and Mary Cassell was the centerpiece, enlarged and mounted on the wall with a spotlight.

Around it, she displayed the documents, census records, Harriet Cole’s testimony, the Confederate major’s letter, Elizabeth’s note to Helen Marsh.

She included a detailed explanation of how visual signals were used by Underground Railroad networks with examples from other regions.

She set up a timeline showing what was happening in Jefferson County, Virginia during 1862 and how the Cassell family would have navigated that dangerous landscape.

She also included dissenting scholarly opinions.

One panel featured a quote from a historian who argued that many claims about underground railroad signal systems were overstated or invented after the fact.

Rebecca did not hide that critique.

She presented it honestly, then explained why she believed the evidence in this case was strong enough to support her interpretation.

The most powerful part of the exhibition was the final section.

Rebecca had managed to trace Harriet Cole’s descendants through genealogical records.

She contacted them and explained the project.

One of Harriet’s great great granddaughters, a woman named Denise Cole, who lived in Philadelphia, agreed to be interviewed.

Rebecca recorded a short video in which Denise spoke about her ancestors escape and the family’s oral history about the people who had helped her.

“We always knew someone had hidden her,” Denise said in the video.

“My grandmother told me the story when I was a girl.

She said there was a white family, a mother and her daughters who risked everything.

We did not know their names.

We did not know what happened to them, but we knew they existed, and now we know who they were.” Denise attended the exhibition opening.

So did descendants of other families who had been involved in underground railroad networks in the region.

The local newspaper covered it.

Then a regional paper picked it up.

A week later, a writer from a national magazine contacted Rebecca and asked if she could do a feature story.

The attention was both gratifying and overwhelming.

Rebecca received emails from historians, genealogologists, descendants of abolitionists, and people who simply wanted to say thank you for telling the story.

She also received angry messages from people who accused her of distorting history, of imposing modern political views onto the past, of disrespecting the memory of Confederates who had been doing their duty.

She ignored the angry messages and focused on the work.

The journal accepted her article and it was published that summer.

The filmmaker completed a short documentary that aired on a regional PBS station.

The photograph of Elizabeth and Mary Cassell with its missing button and hidden signal became part of the historical record.

A year after the exhibition closed, Rebecca was contacted by the Virginia Museum of History and Culture.

They wanted to acquire the photograph and the related documents for their permanent collection.

They offered to purchase everything from the estate and to create a dedicated display as part of their Civil War exhibition.

Rebecca negotiated with Paul Greg, the realtor, and with Helen Marsh’s distant cousin, who was happy to sell.

The museum paid a fair price, and the photograph found a permanent home.

Rebecca attended the museum’s unveiling of the new display.

The photograph was mounted in a climate controlled case with interpretive panels explaining the castle family’s story and the broader context of resistance networks in border states.

Denise Cole was there along with other descendants of people who had escaped through the region.

A historian from the National Park Service gave a talk about the importance of recognizing the diverse ways people resisted slavery, including the quiet courage of families like the Cassels who operated in the shadows.

At the reception afterward, Rebecca stood in front of the photograph and looked at Elizabeth and Mary Cassell.

She thought about what it meant to be 10 and 8 years old and to live in a house where strangers appeared in the night where soldiers searched the cellar where your mother taught you that sometimes a missing button was the difference between life and death.

She thought about Lydia sewing that dress and making the deliberate choice to leave the button off to wear that absence as a message in a memorial.

The photograph was no longer just an image.

It was testimony.

It was evidence of a system, yes, but also of the people who fought against that system, who made choices that could have gotten them killed, who passed down stories so that one day someone like Rebecca would find a cardboard box in an attic and refused to let those stories stay buried.

Portraits are not neutral documents.

They are staged, composed, edited.

They show what the photographer and the subjects wanted the world to see or what they wanted to remember or sometimes what they wanted to hide in plain sight.

Every element in a photograph carries meaning.

The clothes, the setting, the expressions, the objects held or displayed.

And sometimes the meaning is in what is missing.

There are other photographs like this one.

Images that seem ordinary until you notice the hand positioned in a specific way.

The object clutched in a pocket, the shadow that does not quite match, the worn place on a dress or a coat that tells a story the official portrait was never supposed to reveal.

Historians and archivists are finding them slowly in museum collections and family albums and estate sales.

Each one is a fragment of resistance, a piece of a network that operated in secret and left only scattered traces.

The work of recovering those stories is not just academic.

It is an act of restoration.

It gives back agency to people who were erased or flattened into symbols, who were framed by photographers and historians in ways that served power.

When we learn to read photographs differently, to look for the missing button or the frayed thread or the mark in the corner, we begin to see the past not as it was presented, but as it was lived by people who fought in whatever ways they could to survive and to save each other.

The photograph of Elizabeth and Mary Cassell hangs in a museum now.

Thousands of people will see it.

Some will notice the missing button.

Some will read the story and understand what it meant.

And maybe in another attic or estate sale or archive box, someone will find another photograph with its own hidden detail, its own quiet rebellion waiting to be seen.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load