The photograph sat in a donation box for three years.

Most staff at the Maryland

Historical Society walked past it dozens of times.

Then one afternoon in March,

conservator Rachel Oay picked it up to

catalog and something about the hands

stopped her cold.

She had been

documenting Civil War materials for 7

years.

This was supposed to be a routine

processing day.

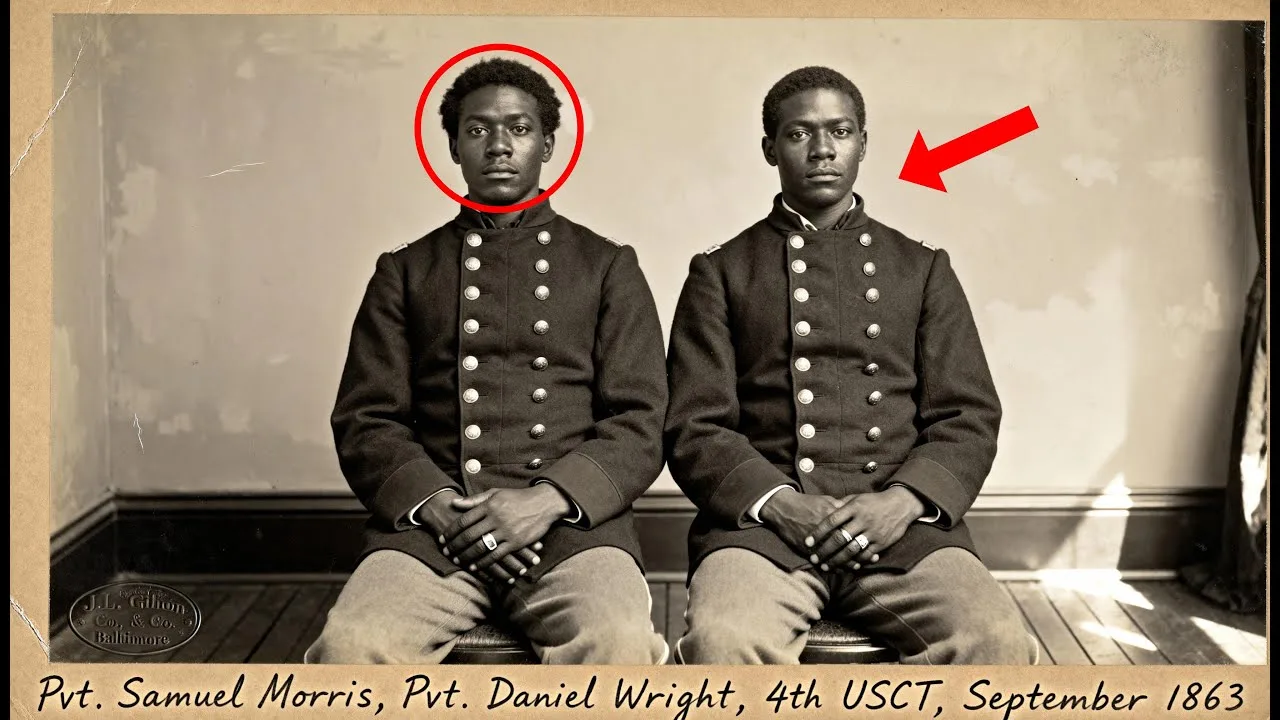

The image showed two

black men in union uniforms seated

against a plain studio backdrop.

Their

postures formal and nearly identical.

Both had their hands folded carefully in

their laps.

Both wore dark wool jackets

with brass buttons.

Both stared directly

into the lens with the particular

stillness that long exposure times

demanded.

Standard military portrait.

She had seen hundreds like it, except

for the rings.

Rachel held the album in print up to the

light from her desk lamp.

On the left

hand of each man, fourth finger, a band

of silver caught the studio

illumination, not just similar rings,

identical rings, same width, same

placement, same deliberate visibility.

The men had positioned their hands to

make sure those rings would show.

In an

era when a single sitting with a

photographer might cost a week’s wages,

nothing in the frame was accidental.

She

set the print down and felt the familiar

weight of a question that would not let

go.

This was not just a pretty old

photo.

Something here was wrong.

Rachel

had built her career on the assumption

that every image contained more than its

surface showed.

She came to conservation

work after teaching art history at a

small college in Baltimore, where she

had spent too many years explaining

decorative portraiture to undergraduates

who wanted to know why any of it

mattered.

The answer she eventually

landed on was simple.

Portraits were

evidence.

They documented power,

aspiration, resistance, and sometimes

violence.

The trick was learning how to

read them.

She adjusted the gooseeneck

lamp and pulled out her magnifying loop.

The photograph had been mounted in a

thin wooden frame with a cardboard

backing that someone had reinforced

decades ago with yellow tape.

She

carefully loosened the corners and

lifted the print free.

The back showed a

studio stamp in faded ink.

JL Gihon and

company photographers Baltimore Amand

beneath that written in pencil in a

steady hand two names Pavit Samuel

Morris Prophet Daniel Wright 4th USCT

September 1863.

She noted the date first.

September 1863

meant these men had enlisted during the

early wave of black recruitment after

the Emancipation Proclamation when the

Union Army was finally allowing formerly

enslaved men to fight.

The fourth United

States colored troops was a Maryland

regiment.

Many of its soldiers had been

enslaved in the state just months before

putting on federal blue.

Next, she noted

the pairing.

Two men, same regiment,

photographed together.

Brothers, maybe

friends, messmates who pulled their

money for a joint sitting to send home

to family.

Except the ring suggested

something else, something the

photographer JL Guehon had been willing

to document but not explain.

Rachel felt

the familiar pull.

If she stopped here,

if she filed the print and moved on to

the next box, this story would stay

buried.

But she had learned years ago

that the images that bothered her were

usually the ones that mattered most.

She

opened her laptop and started a new

research file.

Samuel Morris and Daniel

Wright, fourth USCT.

Time to find out

who they were.

The National Archives

database gave her a starting point.

Both

men had enlistment records.

Morris, age

24, enlisted at Camp Stanton in Maryland

on August 10th, 1863.

Formerly enslaved, owned by a planter

named Caleb Morris in Talbot County.

No

listed next of kin.

Wright, aged 22,

enlisted the same day, same location.

Formerly enslaved, owned by the Tiljman

family, also in Talbat County, no listed

next of kin.

Rachel pulled up census

records, city directories, and newspaper

databases.

She found Caleb Morris easily

enough, a wealthy landowner with tobacco

fields on the Eastern Shore.

He appeared

in an 1860 agricultural census, claiming

ownership of 32 enslaved people.

After

emancipation in Maryland in late 1864,

his fortunes declined rapidly.

By 1870,

he was selling off parcels of land to

settle debts.

The Tilgman family had a

similar trajectory.

Old money, old

tobacco collapsing under the weight of a

war economy that no longer valued their

particular assets.

But Samuel Morris and

Daniel Wright themselves were harder to

trace.

They appeared in the military

records then seemed to vanish.

No

pension applications, no postwar census

entries under those names in Maryland.

It was the familiar problem of

researching people who had been

deliberately erased from official

records for most of their lives.

Enslavers rarely documented the full

names, relationships, or histories of

the people they claimed as property.

Rachel reached out to Dr.

Vernon Hayes,

a historian at Morgan State University,

who specialized in black military

service during the Civil War.

She sent

him a scan of the photograph and the

enlistment details.

He called her 2 days

later.

“The rings,” he said without

preamble.

“You noticed the rings.

That’s

why I called you.” Good, because that’s

the whole story.

He paused and she heard

papers rustling.

I’ve been collecting

marriage cases from the pension bureau

for years.

After the war, thousands of

black widows applied for survivors

benefits and got rejected.

The

government said their marriages weren’t

legal.

Enslaved people couldn’t legally

marry in most states before

emancipation.

So, the pension bureau

ruled that their relationships didn’t

count.

Didn’t matter if a couple had

been together 20 years and raised six

children.

No marriage certificate, no

pension.

So these rings, tokens,

symbols.

I’ve seen references to them in

testimony.

Couples who couldn’t marry

legally would exchange objects, rings,

carved wooden tokens, even pieces of

cloth.

It was a way of saying this is

real, even if the law won’t recognize

it.

And here’s the thing.

Some soldiers

wore those tokens into battle.

They

wanted them visible in photographs.

They

were saying, “I have someone.

I belong

to someone.

The government can call me

contraband property or a recruit or a

laborer with a uniform, but I know what

I am.” Rachel looked at the print again

at the careful positioning of those

hands.

“Do you think Morris and Wright

were married to each other?” Hayes was

quiet for a moment.

“No, I think they

were each married to women who stayed

behind, and they’re wearing their wives

rings as a pair.” a reminder and a

promise.

But here’s what you need to

know.

The fourth USCT saw heavy

fighting.

Petersburg, Richmond, the

final campaigns.

Casualty rates for

colored troops were brutal.

If these men

died in service, their widows would have

had almost no chance of proving

marriage.

No certificate, no pension,

and without names listed as next of kin

in the enlistment records, the

government would have no reason to even

contact them.

Rachel felt something cold settle in her

chest.

So even if they survived the war,

their wives were invisible.

Exactly.

Which means your job is to make

them visible now.

She spent the next two

weeks pulling every thread she could

find.

The regimental history of the

fourth USCT showed that the unit was

organized at Camp Stanton and then sent

to Virginia for training before being

deployed to the front lines.

They fought

at Petersburg in June 1864, then were

assigned to guard duty and eventually

participated in the siege operations

around Richmond.

The unit suffered

significant casualties, though the

records were incomplete.

Many men listed

as missing or died of disease with no

further details.

Samuel Morris appeared

on a muster roll dated December 1863,

marked present, then nothing.

Daniel

Wright lasted longer in the official

record.

He was noted as present through

March 1864, then listed as deserted in

April.

Rachel knew what that often meant.

Soldiers who were sick or wounded

sometimes left hospitals before being

discharged and were labeled deserters

when they didn’t return.

Other times,

men who witnessed atrocities or faced

unbearable conditions simply walked

away.

For black soldiers who faced

unequal pay, harsher discipline, and the

constant threat of being murdered if

captured by Confederate forces,

desertion was sometimes the only act of

self-preservation available.

She found a

small reference in a regimenal

chaplain’s report from May 1864.

Two men of company E have been noted as

absent without leave.

Their messmates

report they departed following news from

home of family illness.

No names given.

Company E.

Morris and

Wright had both been assigned to Company

E.

Rachel drove to Talbat County on a

Saturday in early April.

Crossing the

Bay Bridge as the sun burned off the

morning fog.

The Eastern Shore felt like

a different Maryland, flatter and

quieter with fields stretching toward

Tidal Creeks and small towns that still

carried the names of colonial planners.

She had an appointment at the Talbet

County Historical Society, a small

building in Easton that smelled like old

paper and furniture polish.

The

archavist, a retired school teacher

named Margaret Hensley, brought out

three boxes of materials related to

formerly enslaved people in the county.

“We don’t have much,” she said

apologetically.

“Most of the records

that survived are from the white

families, property deeds, wills, account

books, but starting in the 1920s, a few

local church groups tried to collect

oral histories.

Some of those interviews

mentioned people who enlisted during the

war.

Rachel spent 4 hours going through

fragile Manila folders.

She found

marriage registers from black churches

that had been established after

emancipation, birth, and death records

kept by congregations that knew the

state wouldn’t document their members

lives accurately.

Letters saved by

families who understood that their

histories would otherwise disappear.

In a folder labeled St.

James Church

1865 to 1880.

She found a handwritten

ledger.

The entries were sparse.

Marriages, baptisms, burials.

Halfway

down a page dated November 1863, a

single line.

Joined in matrimony by

Reverend Thomas Grant, Samuel Morris,

and Dileia Freeman, both formerly of the

Morris estate, witnessed by the

congregation, no legal certificate

available.

Rachel’s hands started shaking.

She

turned the page.

Three entries later,

joined in matrimony by Reverend Thomas

Grant, Daniel Wright and Sarah Mason,

both formerly enslaved, witnessed by the

congregation.

No legal certificate

available.

November 1863, 2 months after

the photograph was taken, she looked up

at Margaret.

Do you have anything else

on these families? Dia Freeman, Sarah

Mason.

Margaret shook her head slowly.

Those

names don’t sound familiar, but if they

stayed in the area, they might be buried

in the church cemetery.

St.

James still

exists.

It’s about 3 mi south of here.

The cemetery behind St.

James was small

and overgrown, bordered by a rusted

fence and shaded by old oaks.

Rachel

walked the roads slowly, reading

weathered stones.

Many were simple

markers, just names and dates.

Some had

no dates at all, only initials or the

word mother or child.

Near the back

corner, she found a stone so worn that

the inscription was almost illeible.

She

crouched down and traced the letters

with her finger.

Dileia Morris, 1840 to

1867.

Next to it, a smaller stone.

Infant

Morris, 1866.

Rachel sat back on her heels.

27 years

old.

Dileia had been 23 when Samuel

enlisted.

She had waited for him,

married him in a ceremony that meant

everything and nothing, then died 3

years after the war ended along with her

baby.

She searched the rest of the

cemetery, but found no stone for Samuel

Morris, no stone for Sarah Mason or

Daniel Wright either.

Back at her

office, Rachel contacted the Hull

National Archives again and requested

full pension records for Maryland

soldiers from the fourth USCT.

It took 3

weeks for the files to arrive, scanned

and uploaded to a shared drive.

She

found Dileia Morris in a file dated

March 1866, an application for a widow’s

pension filed 8 months after the war

ended.

The handwriting was careful but

unpracticed, probably written by a

church scribe on Dileia’s behalf.

I am

the widow of Samuel Morris, who served

in the fourth United States Colored

Troops.

He died of fever at Point

Lookout Hospital in February 1865.

I was married to him in November 1863 at

St.

James Church in Talbot County.

I

asked for the pension due to me as his

lawful wife.

Clipped to the application

was the bureau’s response.

A form letter

with certain phrases underlined in red

ink.

Your application has been reviewed.

No record of a legal marriage

certificate has been provided.

The

ceremony you described took place prior

to the abolition of slavery in Maryland

and therefore cannot be recognized as a

valid marriage under federal law.

Furthermore, you are not listed as next

of kin in the solders’s enlistment

records.

Your claim is denied.

Rachel

read it three times.

Samuel Morris had

died in February 1865, 2 months after

Maryland abolished slavery in November

1864, but his marriage had been

performed a year before that while he

was still legally considered enslaved

property.

The timing made his union

invalid in the eyes of the government.

The fact that he had listed no next of

kin because doing so might have

endangered Dia or given his former

enslaver a claim on her now worked

against her entirely.

She found Sarah

Mason’s file next.

Nearly identical

circumstances.

Daniel Wright had

survived the war but died in 1869,

likely from lingering illness related to

his service.

Sarah applied for a widow’s

pension in 1870.

Same denial, no legal

marriage certificate, not listed as next

of kin.

Rachel pulled up the photograph again

and stared at those rings.

These men had

known.

They had known that the

government would not protect the people

they loved.

So, they had carried proof

of those relationships on their bodies.

They had sat for a portrait, knowing it

might be the last image their wives

would have, and they had made sure the

rings were visible.

But it had not

mattered.

The system was designed to

erase people like Dileia and Sarah, and

it had worked exactly as intended.

She

reached out to Dr.

Hayes again.

I found

their widows.

Both denied pensions.

How many marriage cases did you find?

Two, but I’m guessing it’s part of a

bigger pattern.

Try thousands.

Hayes

said after the war, the pension bureau

processed tens of thousands of claims

from widows of black soldiers.

They

rejected the majority.

Sometimes the

women were told their marriages weren’t

legal.

Sometimes they were told they

couldn’t prove the soldier had died in

service.

Sometimes they were just told

they had filed the paperwork wrong.

The

bureau set up an impossible standard,

then blamed the women for not meeting

it.

And here’s the thing, white widows

got their pensions.

Even if their

marriage certificates were lost in a

fire or a courthouse flood, even if the

paperwork was incomplete, there was

usually some bureaucrat willing to vouch

for them, some community leader who

could write a letter.

Black women didn’t

have that.

They had churches and

communities that kept their own records,

but the government didn’t consider those

records legitimate.

Rachel thought of Dileia Morris dying at

27 with an infant, probably in poverty

with no federal support despite the fact

that her husband had died serving the

United States.

This isn’t just about

marriage rights.

No, it’s about every

system working together to make sure

black people stayed poor and powerless

even after emancipation.

You couldn’t own property if you

couldn’t prove your identity.

You

couldn’t claim an inheritance if you

couldn’t prove your marriage.

You

couldn’t get a pension if the government

decided your relationship didn’t count.

Every single piece was designed to

maintain the same hierarchies that had

existed under slavery.

Rachel scheduled

a meeting with her supervisor, the

director of collections at the

historical society, a careful man named

Paul Deckard, who had spent 30 years

managing donor relationships and board

expectations.

She brought printed copies

of everything, the photograph, the

enlistment records, the church ledger,

the pension denials, the gravestone.

Paul studied the materials in silence.

Then he said, “This is a remarkable

find.

It’s more than a find.

It’s

evidence of a systematic campaign to

deny black veterans families the

benefits they were legally entitled to.

I agree.

The question is how we present

it.

Rachel kept her voice level.

We

presented as what it is.

Two soldiers

who loved their wives, wore their rings

into service, and died knowing the

government would abandon the people they

left behind.

And we explained that this

wasn’t an isolated case.

It was policy.

Paul set the papers down carefully.

We

have donors whose families fought for

the Union.

They like to think of the war

as a noble cause.

This kind of story

complicates that narrative.

The war was

a noble cause.

Ending slavery was a

noble cause.

But that doesn’t mean the

government treated black soldiers and

their families with dignity or fairness.

Both things can be true.

I’m not

disagreeing with you, Rachel.

I’m saying

we need to be strategic.

If we center

this story around government failure and

institutional racism, we’ll lose support

from people who want to celebrate union

heroism, then we’ve been telling the

wrong story for 160 years.

Paul

sideighed.

Let me talk to the board.

We

have a planning meeting in 2 weeks for

the fall exhibition schedule.

I’ll

propose a small display around this

photograph and see what kind of

resistance I get.

The board meeting, according to Paul,

went about as well as expected.

Three

members thought the story was important

and should be featured prominently.

Two

members worried about donor reactions.

One member, a retired banker whose

great-grandfather had served in the

Maryland Volunteers, suggested that

Rachel was reading too much into the

photograph and that the rings might mean

nothing at all.

Paul reported all of

this to Rachel in his office on a

Tuesday afternoon, speaking carefully.

I got approval for a display case.

One

case part of the Civil War Gallery.

You

can include the photograph, some

explanatory text, and a selection of

supporting documents.

They want it

framed as a story of resilience and

community rather than a story of

government failure.

Rachel felt

something sharp in her chest.

We can’t

tell this story honestly if we’re not

allowed to name what happened.

I’m not

saying you can’t name it.

I mean saying

you need to balance the critique with

something affirmative.

Show how these

communities kept records, how they

honored marriages even when the

government didn’t, how they resisted

eraser.

That’s the story that will get

people to engage.

She thought about it

for a long moment.

I want to contact

descendants.

If Dileia and Sarah had

family, if their stories were passed

down, I want to include their voices.

Paul nodded slowly.

That’s good.

That’s

exactly the kind of thing that makes

this feel less like an accusation and

more like a restoration.

Rachel returned to Talbot County and

spent a week talking to anyone who would

meet with her.

She visited St.

James

again and spoke with the current pastor,

a woman named Reverend Lydia Cross, who

had been born in the county and whose

grandparents had attended the church in

the 1920s.

Reverend Cross pulled out an old

membership book and showed Rachel

annotations written by long ago church

secretaries.

People used to write notes

in the margins, she said.

Births,

deaths, family connections.

The official

records didn’t care about us, so we kept

our own.

One note penciled next to

Dileia Morris’s name in the 1867 burial

record said, “Sister to Clara Freeman,

mother to Stillborn son, widow of Union

soldier Samuel Morris, denied pension,

but held in honored memory by this

congregation.”

Clara Freeman.

Rachel traced the name

through church records and found her

again in a 1900 census living in Easton

with her daughter.

The daughter, Mary

Freeman, had married a man named Joseph

Turner.

Their children were listed in

later census records.

One granddaughter,

Evelyn Turner, had lived until 1998.

It

took Rachel two more weeks, but she

eventually found Evelyn Turner’s

obituary in a Baltimore newspaper.

Survived by a son, Michael Turner,

living in Columbia, Maryland.

She called

the number listed in the phone book and

explained who she was and what she had

found.

Michael Turner listened in

silence.

Then he said, “My grandmother

used to tell a story about a relative

who married a soldier during the Civil

War.

I never knew if it was true or just

family mythology.” She said that the

woman’s husband died and the government

wouldn’t give her anything because they

said black people’s marriages didn’t

count.

She said it was one of the

reasons our family didn’t trust

institutions.

It was true.

Rachel said, “And I have

proof.” They met at the historical

society a week later.

Michael brought

his wife and his adult daughter.

Rachel

showed them the photograph, the church

record, the pension denial, the

gravestone.

Michael stared at the image

of Samuel Morris for a long time.

“He

looks like my uncle,” he said quietly.

“Same jaw, same way of holding himself.”

His daughter, who worked as a

parallegal, read through the pension

denial with a lawyer’s eye.

This is

monstrous, she said.

They created a

system where it was impossible to win.

That was the point, Rachel said.

Michael

looked at her.

What happens now?

We tell the story.

I’m putting together

an exhibition.

I want to include your

family’s voice if you’re willing.

I want

people to know that Dileia wasn’t just a

name in a file.

She was your great great

great grandmother and she deserved

better.

He nodded slowly.

Yes, do that.

The exhibition opened in September,

exactly 160 years after the photograph

had been taken.

Rachel built it around

the single image enlarged and mounted on

the main wall of the Civil War Gallery.

Next to it, she placed text panels

explaining the context.

The enlistment

of black soldiers.

The Union Army’s

refusal to recognize marriages.

The

pension bureau’s systematic denial of

claims.

The church’s role in keeping

records in honoring relationships that

the state would not acknowledge.

She

included scans of the church ledger, the

pension applications, and the bureau’s

denial letters.

She included a

photograph of Dileia’s gravestone.

and

she included a recorded interview with

Michael Turner, his voice calm and clear

over speakers in the gallery.

My

grandmother used to say that history

tries to disappear people like us, he

said in the recording.

That’s why we

have to remember.

That’s why we have to

tell these stories ourselves.

Dileia

Morris mattered.

Sarah Mason mattered.

They were real women who loved real men

and they were erased by a government

that didn’t want to pay them what they

were owed.

That’s not ancient history.

That’s a pattern we’re still fighting.

The exhibition drew attention.

A local

paper ran a story.

A historian from the

National Museum of African-Amean History

and Culture reached out to say they

wanted to include the photograph in

their database.

Visitors stood in front

of the image for long stretches, reading

every word of the text panels, staring

at those rings.

Rachel stood in the

gallery one afternoon and watched a

woman with two children stop in front of

the display.

The woman read silently,

then bent down and pointed to the rings.

“See those,” she said to her kids.

“They

wore those so people would remember they

were loved.” That night, Rachel sat in

her office and thought about all the

other photographs in the collection.

Thousands of images, families posed in

their Sunday best, workers lined up in

front of factories, children standing in

fields.

How many of them contain details

like this?

small visual evidence of resistance or

survival or love that no one had thought

to look for.

She pulled out a folder of

tint types from the 1870s, images

donated by a family in Annapolis.

In the

third one, she noticed something.

A

woman standing slightly apart from a

group holding a small book.

Rachel

zoomed in with her loop.

The book’s

cover had lettering.

She could just make

out the words.

Register of deeds.

She

felt the familiar pull of a question

that would not let go.

Old photographs

are not neutral objects.

They were

created by people with intentions,

viewed by people with assumptions, and

preserved by institutions that made

choices about what mattered.

For more

than a century, the portrait of Samuel

Morris and Daniel Wright was just

another image of Union soldiers, notable

mainly for the fact that the subjects

were black.

The rings were visible, but

no one thought to ask what they meant.

No one connected them to the pension

files, the church records, the

gravestones in overgrown cemeteries.

That silence was not accidental.

The

same forces that denied pensions to Dia

Morris and Sarah Mason also shaped which

stories got told and which got buried.

Textbooks celebrated Union victory

without mentioning that black veterans

families were systematically

impoverished after the war.

Museum

displays honored military service

without explaining that the government

refused to honor the marriages of the

men who served.

Even well-meaning

historians often treated these details

as footnotes rather than central facts.

But the evidence was always there in

folded hands and visible rings.

In

church ledgers kept by congregations who

knew the state would not document their

lives.

In the testimony of widows who

filed claims knowing they would be

rejected but filing anyway because

silence was worse.

In the stories passed

down through families, told and retold

until someone finally listened.

Photographs like this one exist in every

archive, every museum collection, every

family album.

They show people

positioned carefully, holding objects

that mattered, wearing symbols that

carried weight.

They were taken at

moments when the camera felt important

enough to justify the cost, which means

something was at stake.

And if we learn

to read them, if we stop seeing them as

decorative artifacts and start seeing

them as evidence, they can tell us what

the official records tried to erase.

Samuel Morris and Daniel Wright wore

their wives rings into a photographers’s

studio in September 1863.

They sat with

their hands folded so the rings would

show.

They did not know if they would

survive the war, but they knew this

image might.

And in the end, that choice

mattered because 160 years later, those

rings brought Dileia Morris back into

the

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load