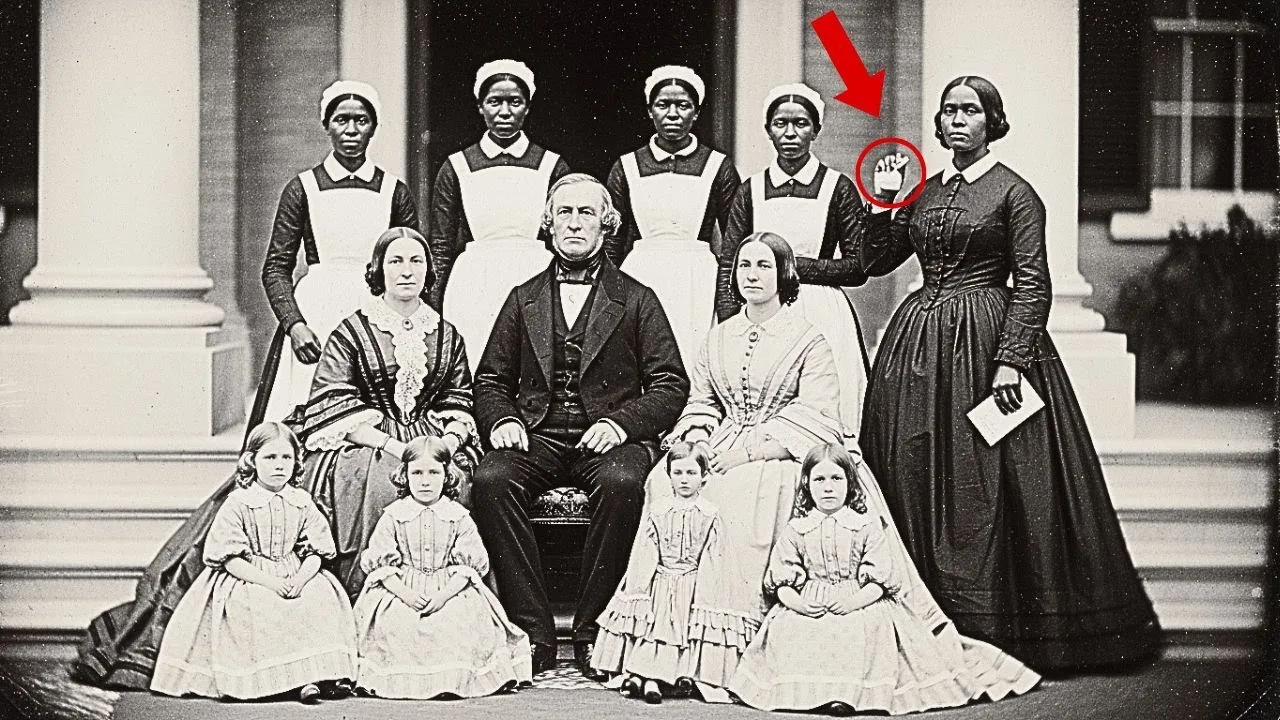

I. The Photograph That Hid a Revolution in Plain Sight

This 1859 plantation portrait looks peaceful—until you see what’s hidden in the servant’s hand.

Dr.

Sarah Mitchell stood in the climate-controlled archive of the Virginia Historical Society, her eyes fixed on a daguerreotype that had arrived in an unmarked box three days earlier.

The photograph showed the Asheford family of Richmond, Virginia, posed formally on the steps of their plantation manor in 1859.

Master Jonathan Asheford sat centered, his wife beside him, their three children arranged like porcelain dolls.

Behind them, barely visible in the composition, stood five enslaved servants in their formal house attire.

At first glance, it was a typical antebellum portrait—wealthy planters displaying their prosperity and social standing.

But something about the posture of one servant caught Sarah’s attention during her initial examination.

The woman stood slightly apart from the others, her face turned at an unusual angle.

Sarah leaned closer, her breath catching.

In the servant’s right hand, partially obscured by the folds of her dark dress, was something that shouldn’t be there—a piece of paper folded tightly, held with deliberate tension.

In hundreds of plantation photographs she’d examined, Sarah had never seen an enslaved person holding anything in a formal portrait.

Everything was controlled, orchestrated, designed to project a specific image of the antebellum South.

She reached for her digital camera and began taking high-resolution photographs of the daguerreotype, focusing on the servant’s hand.

The paper was undeniable, impossible to explain away as a shadow or artifact of the photographic process.

“This changes everything,” Sarah whispered to the empty room.

II.

The Woman With the Paper

Sarah spent the next morning researching the Asheford family.

Property records showed that Jonathan Asheford owned a tobacco plantation called Riverside Manor, employing forty-seven enslaved workers in 1859.

He was a respected member of Richmond society, serving on the city council and attending St.

John’s Episcopal Church.

The daguerreotype had been created by Marcus Webb, a traveling photographer who documented wealthy families throughout Virginia between 1855 and 1861.

His ledgers, preserved at the Library of Virginia, confirmed the sitting date: August 14th, 1859.

Sarah examined Webb’s other work, studying dozens of plantation portraits.

None showed servants holding anything.

The standard composition placed enslaved people as background elements—symbols of wealth rather than individuals with agency.

She returned to the original photograph, using specialized software to enhance the image.

The paper in the servant’s hand became clearer.

It appeared to be folded multiple times, small enough to conceal, but large enough to contain writing.

Sarah contacted her colleague, Dr.

Marcus Reynolds, a historian specializing in enslaved resistance movements.

He arrived at the archive within an hour, his weathered face showing immediate interest when he saw the photograph.

“That’s deliberate,” Marcus said, adjusting his glasses.

“She’s holding that paper at precisely the right angle to be captured by the camera, but not obvious to anyone looking at the original sitting.”

“Who was she?” Sarah wondered aloud.

Marcus pulled up the Asheford Plantation records on his laptop.

According to the 1860 census slave schedule, there were seven women working in the main house, but there are no names—just ages and descriptions.

They studied the woman in the photograph.

She appeared to be in her mid-thirties, tall with strong features and intelligent eyes that seemed to stare directly through time.

III.

The Search for Clara

Sarah drove to Richmond the next day, the August heat reminding her she was retracing steps taken in the same month 166 years earlier.

Riverside Manor no longer existed—a highway interchange now occupied the land where tobacco once grew.

But the Richmond Museum of the Confederacy held extensive Asheford family papers.

The archivist, an elderly woman named Dorothy, led Sarah to a cramped research room.

“The Asheford collection isn’t frequently requested,” Dorothy said, gesturing to three archive boxes.

“Most of it is business correspondence and legal documents.”

Sarah worked methodically through plantation account books, supply orders, and letters.

Jonathan Asheford’s neat handwriting detailed crop yields, market prices, and expenses.

The enslaved workers were listed as property—valued and inventoried like livestock.

Then, in a letter dated September 1859, just one month after the photograph, she found something unusual.

Jonathan wrote to his brother in Charleston: “We’ve had troubling incidents.

Several of the house servants have been acting peculiarly.

I’ve increased supervision and curtailed their movements.

Whatever notions they’ve acquired must be stamped out before they spread.”

Sarah photographed the letter, her mind racing.

What had happened in that one month gap? What had the photograph captured that Jonathan only recognized later?

She continued searching and found a bill of sale dated October 1859.

Jonathan had sold three enslaved women to a buyer in New Orleans—a common tactic for removing troublesome individuals.

The sale was rushed, the price slightly below market value.

Dorothy returned with tea.

“Finding anything interesting?”

“Maybe,” Sarah said carefully.

“Do you know if any Asheford descendants still live in Richmond?”

“There’s Elizabeth Asheford Monroe.

She’s in her eighties.

Lives in the Fan District.

Her family donated these papers in 1972.”

IV.

Family Secrets and Hidden Resistance

Elizabeth Asheford Monroe lived in a narrow Victorian townhouse painted pale yellow.

She welcomed Sarah into a parlor crowded with antiques and faded photographs.

At eighty-three, Elizabeth moved slowly but spoke with sharp clarity.

“My family’s history isn’t something I’m proud of,” Elizabeth said, settling into a velvet chair.

“But I believe in facing truth, not hiding from it.”

Sarah showed her the 1859 daguerreotype on her tablet.

Elizabeth studied it through reading glasses, her expression thoughtful.

“I’ve never seen this photograph,” Elizabeth said quietly.

“My grandfather, Jonathan’s grandson, destroyed most images from the plantation years.

He said the past should stay buried.”

“Do you know why?”

Elizabeth set down the tablet.

“There were family stories—whispers about an incident in 1859, something that frightened Jonathan badly.

My grandmother mentioned it once when I was young.

She said servants had been plotting something dangerous that Jonathan discovered it just in time.”

“What kind of plot?”

“She never said specifically, but she mentioned a woman named Clara who worked in the house.

Clara was educated, taught herself to read by stealing books.

Jonathan found out and had her sold south along with two others.”

Sarah’s heart raced.

“Clara.

Do you remember anything else about her?”

Elizabeth stood slowly and moved to an antique secretary desk.

She withdrew a small leather journal.

“This belonged to my great-great-grandmother, Jonathan’s wife Margaret.

She kept brief daily entries.

I’ve read it only once.

The content disturbed me.”

She opened to an entry dated August 1859: “Jay commissioned the family portrait today.

The photographer was efficient, though I noticed Clara standing strangely, holding herself with unusual tension.

Jay dismissed my concerns.”

Another entry, September 12th, 1859: “Jay has sold Clara, Ruth, and Diane.

He says they were corrupted by abolitionist ideas, that they posed a threat to our safety.

I am relieved but troubled.

Clara always served faithfully.”

V.

Connecting Clara to Resistance Networks

Sarah contacted the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati, speaking with Dr.

James Washington, an expert on enslaved resistance networks in the Upper South.

She emailed him the enhanced photograph showing the paper in Clara’s hand.

James called her back within hours, his voice urgent.

“Sarah, this is extraordinary.

Do you understand what you might have here?”

“Tell me.”

“In 1859, Virginia was a powder keg.

John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry happened in October that year, just two months after this photograph.

But the planning for that raid and other resistance activities had been underway for months.

Underground Railroad conductors were active in Richmond, helping people escape and spreading information.”

“You think Clara was involved?”

“Look at the timing.

August photograph, September discovery, October sales, then Brown’s raid in October, which terrified every slaveholder in Virginia.

If Clara was connected to an underground network and Jonathan discovered evidence of it, he would have acted swiftly.”

Sarah felt the pieces aligning—the paper in her hand.

“Could it be a message?”

“Possibly a map, a coded letter, contact information.

Enslaved people used incredibly creative methods to hide and transmit information, embedding evidence in a formal photograph that would never be closely examined.

That’s brilliant.”

James continued, “Richmond had an active network of free Black people and sympathetic whites who aided escapees.

There’s documented evidence of messages being passed through household servants who had more freedom of movement than field workers.”

“How do I find out what was on that paper?”

“You probably can’t, not directly, but you might be able to trace Clara’s journey after the sale.

New Orleans slave market records sometimes survived.

And if she was involved in resistance activities, there might be records in abolitionist archives.”

VI.

Tracing Clara’s Journey South

Sarah flew to New Orleans on a humid September morning.

The Amistad Research Center occupied a modern building on the Tulane University campus, its archives preserving the stories of people who had been bought, sold, and transported through one of America’s largest slave markets.

Dr.

Patricia Green, the center’s director, met Sarah in her office.

“The fall of 1859 was a busy time in the New Orleans market,” Patricia explained.

“After John Brown’s raid, slaveholders throughout the Upper South became paranoid about unreliable servants.

Many were sold south as punishment or preventative measure.”

She pulled up digital records on her computer.

“Sales were recorded by the notary who handled the transaction.

You said October 1859?”

“Yes.

Three women from Richmond—Clara, Ruth, and Diane.

Sold by Jonathan Asheford.”

Patricia searched the database, her fingers moving quickly across the keyboard.

“Here.

October 28th, 1859.

Three women ages thirty-four, twenty-eight, and forty-one, sold to Jacques Beaumont, a sugar plantation owner in St.

James Parish.”

Sarah leaned forward.

“Are there any other records—medical examinations, descriptions?”

Patricia clicked through several documents.

“Yes, here.

The notary noted that one woman, aged thirty-four, had unusual scarring on her hands consistent with burns.

That was sometimes code for someone who had been punished for handling forbidden materials like books or papers.”

“That could be Clara.”

“There’s more,” Patricia said, her voice dropping.

“Six months later, in April 1860, Jacques Beaumont filed a report with the St.

James Parish Sheriff.

One of the women he’d purchased from Virginia had escaped.

The report describes her as intelligent, literate, and potentially dangerous.”

Sarah felt her skin prickle.

“Did they catch her?”

Patricia shook her head.

“There’s no follow-up record.

Either she was never found or Beaumont chose not to pursue it further.

By 1860, some owners were becoming reluctant to advertise escapes.

It suggested weakness and encouraged others.”

VII.

The Underground Railroad Connection

From New Orleans, Sarah traveled to Philadelphia, where the Friends Historical Library housed Quaker records dating back to the 1680s.

The library specialist in Underground Railroad documentation, Thomas Miller, had been expecting her.

“I’ve been researching since you called,” Thomas said, leading Sarah to a private research room.

“The spring of 1860 was a critical period.

After John Brown’s execution in December 1859, Underground Railroad activity intensified.

People were determined to honor his sacrifice by accelerating freedom efforts.”

He spread several documents across the table—letters, journals, and coded passenger lists maintained by Quaker conductors.

“There were three main routes from Louisiana northward.

The most successful ran through Texas, then north through Missouri to Iowa and Illinois.”

Thomas pointed to a journal entry dated May 1860, written by a Quaker conductor named Rebecca Walsh: “Received three travelers from the Gulf region, two men, one woman.

The woman bore signs of hard labor, but demonstrated remarkable education and determination.

She carried knowledge of networks in Virginia and spoke of unfinished business.”

“Could that be Clara?” Sarah asked.

“It’s possible.

Rebecca was operating a station in southeastern Iowa at that time.

She used coded language—‘travelers’ meant freedom seekers, ‘Gulf region’ indicated they’d come from Louisiana or Mississippi.”

Thomas showed Sarah another document, a letter from Rebecca to a fellow conductor in Philadelphia: “The woman with Virginia connections has proved invaluable.

She possesses information about sympathetic contacts in Richmond and detailed knowledge of household routines and prominent families.

She wishes to return to help others, but understands the danger.”

Sarah photographed the documents carefully.

“Did she return to Virginia?”

“I haven’t found direct evidence yet, but there are references in later correspondence to a woman working as a conductor in the Richmond area during late 1860 and early 1861—someone with inside knowledge of wealthy households, someone who could move through certain spaces without arousing immediate suspicion.”

He pulled out one more document, a brief notation in a ledger from December 1860: “C.

Reports successful passage of four souls from the Asheford Connections.

Message delivered.”

VIII.

Decoding the Photograph

Back in Virginia, Sarah arranged to meet with Marcus Reynolds at the University of Richmond’s digital humanities lab.

They’d obtained permission to use advanced imaging technology on the original daguerreotype, hoping to reveal more details about the paper in Clara’s hand.

The technician, a young woman named Lisa, carefully positioned the daguerreotype under a specialized multispectral camera.

“This technology was developed for analyzing historical manuscripts,” Lisa explained.

“It can detect ink traces, highlight texture variations, and reveal details invisible to the naked eye.”

They watched as the computer processed the images, applying different spectral filters.

The photograph appeared on the monitor in extraordinary detail—every fold of fabric, every shadow, every subtle variation in tone.

“There,” Marcus said suddenly, pointing at the screen.

“Look at her hand.”

Lisa zoomed in on Clara’s right hand.

The paper she held wasn’t just folded.

There were marks visible on its surface—tiny impressions that suggested writing.

“Can you enhance that section?” Sarah asked.

Lisa adjusted the settings, isolating the paper and applying maximum contrast.

Slowly, incredibly, shapes emerged.

Not clear letters, but definite markings—what appeared to be a crude map with several points marked, and beneath it, a series of symbols.

Marcus pulled out his phone and compared the image to examples from his research.

“These symbols are consistent with codes used by Underground Railroad networks.

This mark,” he pointed to a star-like shape, “typically indicated a safe house or contact point.”

“She was holding a map,” Sarah whispered.

“Right there in the middle of a formal family portrait, Clara was documenting the network’s locations.”

Lisa enhanced another section, revealing what appeared to be initials: JWMC RL—possibly the contacts Clara was working with.

“This is evidence of organized resistance,” Marcus said, his voice filled with emotion.

“Clara didn’t just escape.

She was actively documenting the people who could help others escape.

And she found a way to preserve that information in a place no one would think to look.”

IX.

Clara’s Network and Legacy

Sarah spent the next two weeks tracing the initials from Clara’s map through Richmond church records, free Black community registers, and abolitionist society documents.

Slowly, names emerged—James Washington, a free Black carpenter; Mary Connor, a white Quaker seamstress; Robert Lewis, an Irish immigrant who operated a boarding house near the river.

Each had been documented in various historical records as Underground Railroad participants, though none had ever been definitively proven.

Clara’s map provided the missing connection, evidence that they’d worked together as part of a coordinated network.

But the most remarkable discovery came from the National Archives, where Sarah found a report filed by a Confederate provost marshal in March 1861, just weeks before the Civil War began.

Intelligence received regarding escaped slave named Clara, last sold from Asheford Plantation in Richmond.

Subject reportedly returned to Virginia and is suspected of aiding runaways.

Efforts to locate and apprehend have been unsuccessful.

Subject demonstrates unusual intelligence and network connections.

The report was filed by Jonathan Asheford himself, who had been appointed to a security position as war tensions escalated.

His handwriting—the same neat script from his 1859 letters—betrayed his frustration.

This woman continues to evade capture and undermines the proper order.

Her activities represent a direct threat to stability.

Sarah found one more document, a brief entry in a Union Army record from April 1865 after Richmond fell to federal forces.

A contraband camp officer noted: Interviewed a woman named Clara, approximately forty years old, who claims to have worked as a conductor in Richmond throughout the war years.

She provided valuable intelligence about Confederate supply routes and sympathetic contacts within the city, recommending her for recognition.

Clara had survived.

Not only survived, she’d returned to the very place where she’d been enslaved and spent five years helping others find freedom while the Confederacy searched for her.

X.

The Exhibition: Clara’s Story Unveiled

Sarah stood in the Virginia Historical Society’s gallery where the 1859 daguerreotype now hung with a new exhibition label.

Elizabeth Asheford Monroe stood beside her, along with Marcus Reynolds and a small group of descendants that genealogical research had identified as likely connected to Clara.

Among them was an elderly man named Robert Jackson, whose great-great-grandmother had escaped from Richmond in 1861 with help from an unnamed woman conductor.

Family oral history had preserved the story, but never the helper’s name.

“Clara,” Robert said softly, staring at the photograph.

“After all these years, we know who saved my ancestor.”

The exhibition label read:

This 1859 plantation portrait captured more than its subjects intended.

The woman standing at the right, later identified as Clara, holds a folded paper containing a map of Underground Railroad contacts in Richmond.

After being sold to Louisiana for suspected resistance activities, Clara escaped, returned to Virginia, and spent the Civil War years as a conductor, helping dozens reach freedom.

Her deliberate inclusion of the map in this formal photograph represents an extraordinary act of courage and resistance, hiding evidence of organized liberation in plain sight.

Sarah had worked with a coalition of historical societies and descendants to ensure Clara’s story would be permanently preserved.

The original map symbols had been decoded and cross-referenced with other Underground Railroad records, revealing a network more extensive than previously documented.

Elizabeth approached Sarah quietly.

“Thank you for uncovering this.

My family’s history includes great evil, but knowing that Clara fought back—that she won—makes it bearable to face.”

Sarah looked at the photograph one more time.

Clara’s eyes seemed to look directly at her across 166 years, filled with determination and intelligence.

In her hand, barely visible unless you knew to look, was evidence that enslaved people had never been passive victims.

They’d been active resistors, documenting their own liberation networks and fighting for freedom with remarkable courage and creativity.

The photograph, once a symbol of antebellum power, had become something entirely different—a testament to Clara’s resistance, preserved in the one place her enslavers would never think to look.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load