The image had sat in a

university archive for decades,

cataloged as a simple betroal portrait.

It looked tender, almost hopeful, until

the day a curator named Maria Reeves

held the plate under magnification and

saw the seal pressed into the wax.

Maria

had been working in the Louisiana

collection at Tain for 11 years.

She had

seen hundreds of dgeray types from

Antabbellum, New Orleans.

Images of

merchants and their families, society

portraits, post-mortem keepsakes.

This

one had been donated in 1923 by the

estate of a minor shipping family, boxed

with two dozen other plates, and never

properly examined.

The donor note said,

only betroal portrait circa 1856.

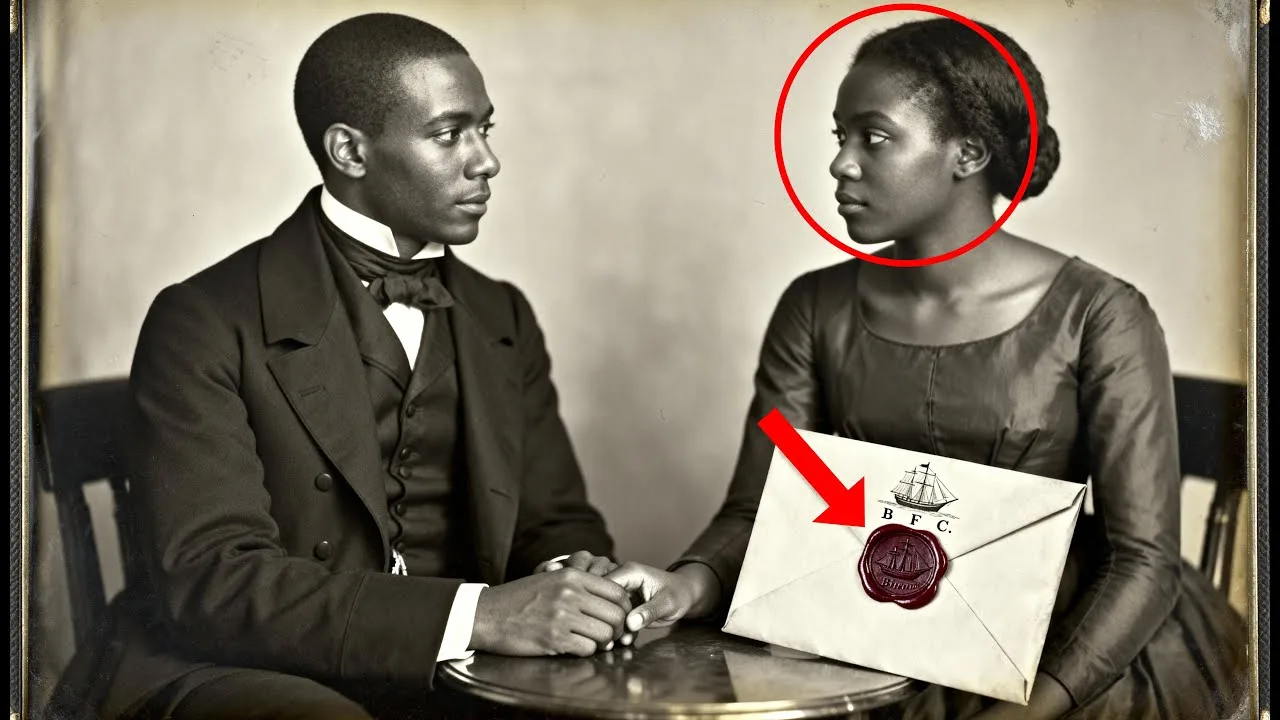

The couple sits close but not touching

except where their hands meet over a

folded document on a small table between

them.

The man is perhaps 30, clean

shaven, wearing a dark coat that

suggests middling prosperity.

The woman

looks younger, 20 at most, her dress

plain but well-fitted, her hair pulled

back in the style free women of color

wore in the city.

Her expression is

calm, almost blank.

His face shows

something harder to read.

Pride maybe,

or something closer to defiance.

Maria

adjusted the angle of the light.

The

dgerayotype silver surface threw back

reflections, but at the right tilt,

details emerged that a casual glance

would miss.

The paper beneath their

joined hands was folded twice, creating

a thick packet.

A red wax seal held it

closed.

She leaned closer.

The seal bore

an impression, not a family crest or

initial, something else.

She reached for

the stereoscope they used for fine

detail work.

The seal showed a ship in

profile and three letters beneath it, B,

F, and C.

Maria sat back.

She knew those

initials.

Benville Factors Collective,

one of the largest slave trading firms

operating out of New Orleans in the

1850s.

Their office had been on Chartra

Street near the St.

Louis Hotel where

the auctions were held.

This was not a

love letter under their hands.

This was

a bill of sale.

Maria had started in

archives because she liked the

quietness, the way old things stayed

still and let you think.

But over the

years, she had learned that no

photograph is ever really still.

Every

image is a decision about what to show

and what to hide.

And the things people

chose to hide in plain sight were often

the things that mattered most.

She had

found death in christening portraits,

poverty beneath fine clothes, violence

in the empty spaces where people should

have been standing.

But this was

different.

This was someone asking the

camera to witness something that should

not have needed witnessing at all.

She

turned the Dgerype case over.

On the

back, written in faded ink, a single

line, Jacqu Lamel, and Seline, June

1856.

No surname for Seline.

That alone told a

story.

Maria photographed the seal under

magnification, then began the research

that would consume the next eight months

of her life.

She started where she always started

with the photographer.

New Orleans had

dozens of dgeraype studios in the 1850s,

most clustered along royal street in

Chartra.

The case had no photographers

mark, but the style of the mat and the

quality of the plate suggested one of

the better establishments.

She pulled

the city directories for 1855 and 1856

cross- referenced with advertisements in

the daily picune.

Three studios were possibilities.

She

wrote to descendants, checked business

records, and finally found a ledger from

Armen Dulock’s studio on Royal Street

that listed a sitting for Jay Lamel in

June of 1856.

No mention of a second subject, which

was common when one of the sitters was

not considered socially equal to the

other.

Census records gave her Jacqu

Lamel, a clerk working for a cotton

factory on Chupitulas Street.

Born in

France, arrived in New Orleans in 1849,

listed as white, living in a boarding

house on Rampart Street.

No property, no

enslaved people in his name, unmarried

as of 1860.

Seline was harder.

She did

not appear in the 1850 census as free,

but the 1860 census showed a Selene

Lamel Mulatto living on Dolphin Street

listed as a seamstress.

The coincidence

of the surname was suggestive, but not

proof.

Many free people of color took

the names of former enslavers or

protectors without any formal

relationship.

Maria needed an expert who

understood the legal architecture of

slavery and freedom in 1850s Louisiana.

She contacted Dr.

Raymond Tibo, a

historian at the University of New

Orleans, who had written extensively on

manum mission practices in the

antibbellum south.

They met in his

campus office on a humid afternoon in

September.

She showed him the Dgera type

on her laptop, zoomed in on the seal.

Raymond leaned forward.

Benville

factors, they handled sales, but they

also processed manumission paperwork

when it was tied to a purchase.

After

1852, Louisiana law required anyone

freeing an enslaved person to post bond

and prove the person could support

themselves.

The process went through the

district court, but the trading firms

often brokered the transaction.

So, this could be a freedom document.

Maria said it could be.

But here’s what

makes this complicated.

If Jacques Lamel

bought Selen’s freedom, the law would

still recognize him as having a

financial interest in her.

She would be

free, but the document connecting them

would look almost identical to a bill of

sale.

In the eyes of the state,

manumission was just another form of

property transfer.

Maria thought about

that.

And if they wanted to marry,

Raymon’s expression darkened.

They could

not.

Louisiana prohibited marriage

between white people and anyone with

African ancestry.

The law was absolute.

Even if she was legally free, even if he

loved her, the state would never

recognize them as husband and wife.

The

best they could do was live together and

hope no one challenged the arrangement.

And if someone did challenge it, their

children would be illegitimate.

Any

property she accumulated could be

disputed.

If he died, she would have no

claim as a widow.

She would be legally

invisible.

Maria asked him to look

deeper into the Benville factors

collective records.

anything that might

reference Jacques Lamel or a woman named

Seline.

She began her own search through

the District Court archives looking for

manumission petitions filed in 1855 and

1856.

It took 3 weeks but she found it.

A petition dated April 14th, 1856 filed

by Jacqu Lamel on behalf of a woman of

color named Seline aged 19 years

currently held by the estate of Madame

Ve Abear.

The petition stated that Jacod

Lamel agreed to pay the sum of $800 for

Selen’s freedom and to post a bond of

$200 guaranteeing that she would not

become a public charge.

The petition

included a sworn statement from Seline

that she possessed skills in needle work

and domestic service and could support

herself as a free woman.

The court

approved the petition on May 30th, 1856.

Two weeks later, they sat for a dgera

type.

But the petition also included

something Maria had not expected, a note

appended by the court clerk.

Petitioner

states intention to marry said woman

pending removal to jurisdiction

permitting such union.

They had told the

court they planned to leave Louisiana.

Maria did not know if that should make

the image more heartbreaking or less.

They had sat for this portrait, knowing

it might be the only formal record of

their bond, the only proof that what

they felt for each other had weigh in

the world.

The folded paper between

their hands was not a symbol of love

triumphing.

It was a map of every

barrier the law had placed in their way.

She needed to understand what it meant

to live in that gap between freedom and

full personhood.

She traveled to New

Orleans, spent a week in the city’s

historical archives and libraries.

She

walked the streets where Jacques and

Seline would have walked.

The old French

Quarter looked polished now, full of

tourists and restaurants, but the bones

of the city were still there.

The

courtyards where enslaved people had

lived in quarters behind the main

houses, the markets where they had been

sold, the churches where free people of

color had worshiped separately from

whites, their names recorded in

different registers.

At the New Orleans

Public Library, she found a parish

record from St.

Augustine Church, the

church established for free people of

color.

A baptism entry from 1858.

Emile,

son of Selene Lamel, free woman of color

and father unknown.

Another entry in 1860.

Margarite, daughter of Selene Lamel,

free woman of color and father unknown.

Father unknown.

The law forced that lie.

Jacques could not be named as the father

because naming him would create a legal

record of an interracial relationship

and that was something the state refused

to acknowledge.

Their children existed

in a legal void connected to their

mother but severed from half their

lineage.

Maria contacted Dr.

Erica

Dorsy, a specialist in 19th century

family law at Howard University.

They

spoke by video call and Maria showed her

the dgerotype in the documents she had

gathered.

This is classic legal eraser.

Dr.

Dorsier Dorsai said the state

created a system where love became

property law where every intimate choice

had to pass through the language of sale

and ownership.

And for the people

trapped in that system, every act of

resistance or preservation was a risk.

Sitting for this portrait was a risk.

Keeping the document visible in the

image was a risk.

They were saying,

“Here is proof.

Here is what we are to

each other.” and the only way they could

say it was by holding the paper that

should never have existed in the first

place.

Maria asked what would have happened if

they had tried to leave Louisiana.

Legally, they could have gone north or

west to a free state.

But think about

what that required.

Jacques would have

had to abandon whatever work or life he

had built in New Orleans.

Seline would

have been traveling with a white man she

could not legally marry, carrying

children whose birth records would mark

them as illegitimate.

They would have

been vulnerable at every checkpoint,

every border, every town where someone

might question their relationship.

And

if they went somewhere that did allow

interracial marriage, they would still

be starting over with no resources and

no legal protection for anything they

had left behind.

Maria thought about the expression on

Selen’s face in the dgeraype.

Not joy,

not hope, just a strange flat endurance.

She went back to the records.

She

searched for evidence that Jacques and

Seline had left New Orleans, but she

found none.

The 1860 census listed

Jacques Lamel, still in the city, still

working as a clerk, still unmarried.

Selene Lamel lived across town with two

children.

There was no documentation

that they shared a household, though

that meant little.

Plenty of interracial

couples in New Orleans maintained

separate addresses to avoid legal

trouble.

But in 1862, the trail ended.

Jacqu Lamel disappeared from the city

directories and census records.

Seline’s

name appeared one more time in the 1870

census, living on Doofine Street, listed

as a widow, though she had never legally

been a wife.

Her children were grown by

then, both listed with occupations.

Emile was a carpenter.

Margarite was a

teacher.

Both used the surname Lamel.

Maria found one more document, a deed

recorded in 1867 showing that Selene

Lamel purchased a small house on Doofine

Street for $300.

The seller was listed

as the succession of Jacqu Lamel,

deceased.

Somehow, despite the lack of

legal marriage, he had left her

something.

Maybe through a trust or an

informal arrangement with his executive,

maybe by structuring the sale to look

like a normal property transaction, the

law made it nearly impossible.

But

people found ways.

That was where the

archival trail ended.

Selene died

sometime before 1880.

Her death

unrecorded in any register Maria could

find.

Her children disappeared into the

sprawl of postwar New Orleans.

Their

descendants scattered or lost to time.

Maria prepared a report for the

university archive outlining everything

she had learned.

She recommended that

the Dgerara type be reinterpreted and

placed in a new context within the

collection with full explanatory text

about manumission law and

anti-misogenation statutes.

She

suggested that it could anchor an

exhibition about the hidden lives of

interracial couples in the antibbellum

south.

The response was cautious.

The

archives director, a careful man named

Robert Schovin, convened a meeting with

the curatorial staff, the head of the

history department, and two members of

the university’s donor relations team.

They gathered in a conference room in

the special collections building.

Maria

presented the Dgerara type on a screen,

walked them through her research, showed

them the documents and the legal

framework that had trapped Jacques and

Seline.

Robert listened carefully, his

hands folded on the table.

When Maria

finished, he spoke slowly.

This is

important work.

I want to be clear about

that, but I need to think about how we

present this publicly.

We have donors

whose families were part of that world.

Some of them have antibbellum portraits

in our collection donated with the

understanding that we would honor their

ancestors.

If we start reinterpreting

every photograph as evidence of

exploitation or violence, we risk

alienating the people who make this

archive possible.

Maria had expected

this.

I’m not asking us to condemn

everyone in every old photograph.

I’m

asking us to tell the truth about this

one.

Jacques and Seline are not

abstractions.

They were real people who

tried to build a life together in a

system designed to prevent exactly that.

The document in this image is proof of

how the law dehumanized them both.

Ignoring that is not neutral.

It is a

choice to keep the story hidden.

One of the donor relations staff, a

woman named Catherine, spoke up.

Could

we present it as a love story? Emphasize

the resilience, the way they found each

other despite the obstacles.

We can do that, Maria said, but we

cannot do it without also naming what

the obstacles were.

This is not a story

about love conquering all.

It is a story

about love constrained by property law,

about two people who could not marry,

whose children were legally erased, who

were forced to live in the margins

because the state refused to see them as

fully human.

That is the story.

If we

soften it, we are lying.

The room was

quiet.

Dr.

Paul Menddees, a historian

specializing in Civil War era Louisiana,

finally spoke.

Maria is right.

This

photograph has been sitting in our

archive for a century, labeled as a

betroal portrait.

Every student, every

researcher who saw it accepted that

story because we did not bother to

question it.

We owe it to Jacques and

Seline and to every other person whose

image we hold to do the work of

understanding what we are actually

looking at.

That is our job.

Robert

nodded slowly.

All right, let us move

forward with a reinterpretation, but I

want the language to be precise,

grounded in the documents.

No

speculation, no melodrama.

Let the facts

speak.

Maria agreed.

She spent the next

two months writing the exhibition text

and working with a designer to create a

display that would give the dgeraype the

context it deserved.

The exhibition

opened in April, a small but carefully

constructed show in the archives public

gallery.

The centerpiece was the dgeray

type enlarged and displayed beside a

translation of the manum mission

petition, the parish baptism records,

and a timeline showing the evolution of

Louisiana’s laws around slavery,

freedom, and marriage.

The text explained how Jacqu Lamel had

purchased Selen’s freedom but could not

marry her, how their children were

recorded without a father, how the law

treated love as a property transaction.

A second panel showed excerpts from

other manumission petitions

demonstrating that Jacques

and Seline were not unique, that

hundreds of people in New Orleans had

navigated the same cruel legal maze.

One

section of the exhibition included oral

histories from descendants of free

people of color in New Orleans, recorded

by researchers in the 1970s and 1980s.

Several spoke about the ways their

ancestors had preserved family stories

that official records refused to tell.

One interview with a woman named Mrs.

Claudine Bertrand stood out.

She

described how her great-g grandandmother

had kept a box of documents, bills of

sale, and manumission papers and refused

to destroy them even though they were

painful reminders of what the family had

survived.

She said people would want to

forget, Mrs.

Bertrand explained in the

recording.

But forgetting is how they

win.

The exhibition drew attention

beyond the university.

A journalist from

the Times Pikyune wrote a feature about

the Dgera type and the research behind

it.

Historians and educators reached out

to ask if the materials could be used in

classrooms and conferences.

Several people contacted the archive

claiming possible family connections to

Selene or Jacques, though none could be

confirmed.

But the most unexpected

response came from a retired school

teacher in Baton Rouge named Vivian

Lamel.

She wrote to Maria saying she had

read the article and wondered if there

might be a connection to her own family.

Her great great-grandfather had been

named Emil Lamel, a carpenter in New

Orleans in the 1870s.

She had a

photograph of him taken later in life.

She also had a small wooden box he had

made with a hidden compartment that held

a single dger type.

Maria arranged to

meet her.

They sat in Vivian’s living

room on a warm Saturday in June.

Vivien

brought out the box, a simple piece of

carpentry, cypress wood with brass

hinges.

She opened the hidden

compartment and removed a dgeraype in a

worn leather case.

It was the same

image, Jacqu and Seline, hands joined

over the folded paper.

He kept it all

his life, Vivien said.

I never knew what

it was.

I thought it was just a picture

of some relatives.

My grandmother told

me once that our family had French

blood, but she did not say much more

than that.

People did not talk about

these things.

Maria felt something

loosen in her chest.

The Darro type in

the archive had been a record.

This one

passed down through a meal was proof

that the story had mattered to the

people who lived it, that it had been

worth preserving.

“Your great

greatgrandfather is in the baptism

records at St.

Augustine Church,” Maria

said gently.

“He was Selen’s son.

His

father was Jacques Lamel, but the law

would not let them record that.

This

image was probably the only proof Emile

had of who his father was.”

Vivien looked at the Dgerara type for a

long time.

“They look so serious,” she

said finally.

“I always thought old

pictures just looked that way because

people did not smile.

But now I think

maybe they had reasons.”

The university made a highresolution

scan of Viven’s Dgeray and displayed it

alongside the archives copy in the

exhibition.

The label explained that was

the same image kept by the family, proof

that what looked like a romantic

portrait was actually a desperate act of

documentation.

The exhibition text was updated to

include Emil’s story and the fact that

descendants still held pieces of the

family history.

The exhibition ran for 6

months.

After it closed, the Dgera type

returned to the archives permanent

collection, but now with a new catalog

entry that told the full story.

Students

and researchers who encountered it would

no longer see a simple betroal portrait.

They would see Jacques and Seline,

caught between love and law, holding the

document that had freed her, but could

not make them equal.

The power of old

photographs lies in what they refuse to

say out loud.

Every portrait from the

19th century is a negotiation with the

camera, a decision about what story to

tell and what evidence to leave behind.

The wealthy used photographs to cement

their respectability, to project a

vision of order and refinement that

often depended on the labor and

suffering of people who were not allowed

in the frame.

But sometimes in the

corners of those images, in the details

no one was supposed to notice, other

stories survived.

The paper beneath

Jacques’s hand should have been

invisible.

It should have been just

another prop in a conventional portrait.

But by keeping it visible, by making

sure the seals showed, by sitting

together as if they had the right to be

seen that way, they created a record

that outlasted the laws designed to

erase them.

For more than a century, no

one looked closely enough to see what

they were holding.

But the evidence was

always there, pressed into wax, waiting

for someone to ask the right questions.

There are thousands of dgera types like

this one sitting in archives and atticss

and estate sales cataloged with stories

that do not quite fit the images.

Portraits of children whose expressions

suggest something other than the

prosperity their clothes imply.

Family

groups where one person stands too far

away or holds themselves too stiffly.

Their presence in the frame a concession

to power rather than affection.

Couples

whose intimacy is visible only in a

single gesture.

a touch of hands over a

document that should not need to exist.

Every photograph is evidence, but

evidence of what depends on whether

anyone is willing to look closely enough

to see what the image is trying to hide

or what it is quietly, desperately

trying to preserve.

have.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load