The swamp light turned everything the color of old paper the first Sunday evening I saw the three graves.

They leaned in a crooked row on the hill behind the main house, stone markers sunk like teeth in rotten gums.

The house itself—Witcom House, though no one called it that anymore—watched from the rise like something left in a hurry.

Shutters hung by one hinge, porch boards warped, vines gnawed at pillars.

There had been grandeur here once.

Now there was humidity and the restless sound of frogs.

The stones had no names, only dates—three men dead in the same year.

On the middle stone, chipped and swallowed by lichen, someone had scratched a line by hand, jagged letters like they’d been cut in temper: They swore on her.

One broke, all paid.

By vocation, I am a man who lives among the dead—or what they leave behind.

Deeds.

Wills.

Contracts.

Letters that should never have been written, never kept.

The Witcom Estate was one more corpse on my desk until a judge ordered someone to ride out and make sense of the scraps.

That someone was me.

The year was 1868.

Slavery had been abolished in law, but not in memory.

Half the ledgers I handled were filled with ghosts traced in human ink, bodies tallied as property.

The Witcom file was worse than most.

Faces changed every election; the file remained: brittle pages held by twine and reluctance.

I should have expected the graves.

I did not expect the feeling they were waiting.

The caretaker—a boy barely twenty, given the house to mind because no one else wanted it—stopped short of the hill, shifting from foot to foot.

“Your papers are inside, sir,” he said.

“You really mean to stay the night?”

“Someone has to,” I said.

“The judge wants inventory.

I can’t carry this house back to town.”

He crossed himself, quick and furtive.

“It ain’t the house that’s the trouble.”

“What is, then?”

He nodded toward the three stones.

“Them.

And the one she had, too.”

“The one who had what?”

He swallowed, sweat shining.

“The slave wife, sir.”

The word hung between us like a diseased limb sewn onto a living body.

“I just keep the place,” he muttered.

“Don’t ask me to tell it.

They say the story’s written down.

You’re hired to read it.”

He left me at the foot of the hill with the crickets and the low clatter of his retreating boots.

I watched him go, then looked back at the stones.

They swore on her.

One broke, all paid.

It could have been superstition, some petty bob of a grudge too stale for the courthouse, or nothing.

But I follow sentences the way other men follow tracks.

So I turned from the graves and went to look for the words that would explain them.

The study still smelled faintly of pipe smoke, though the man who filled it was twenty years in his own grave.

Shelves leaned under law books and ledgers.

Moths had chewed the rug’s edges.

On the oak desk lay a Bible, leather turned shiny from generations of hands.

Behind it, in a cabinet—whose key I’d been given with the property—were bundles of correspondence, a bound ledger, a sheaf of loose pages tied with ribbon.

Atop the stack, as if someone had put it there last and hardest, sat a narrow leather-bound book.

The binding was tight, the page edges uneven—handmade, private.

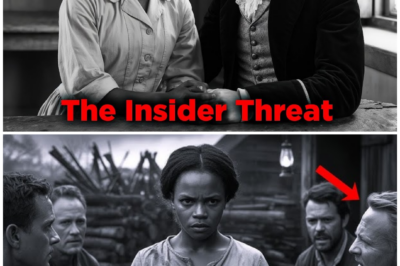

Inside the front cover, in close angular script: Elellanor Whitum, 1844.

Beneath, in a different hand, fainter, hurried, as if added later: Samuel Witcom.

Confession to be delivered if I die.

A prickle moved up my neck—the sensation of being watched—though only the boy remained on the property, and he wouldn’t come near this room after sundown.

I settled, drew breath, and opened the book.

Stories like these begin with a man’s death.

Elellanor wrote, winter of 1843: My husband died in his sleep, with his accounts unbalanced and his sins unconfessed.

He left her the house, land, slaves, debts, and three sons grown enough to drink but not to inherit.

He left her a reputation that flickered between admiration and disgust depending on who owed whom.

She’d grown up ordered, under a father who bred horses and people with the same cold eye.

Her marriage to Henry Witcom was an alliance of land and blood, nothing more.

When he died, she felt no sorrow—only the wind of precariousness.

Cotton had failed three seasons.

Bank men arrived with papers that smelled of damp ink and dwindling patience.

Neighbors talked: The Witcom boys were handsome but strange.

Why had none taken a wife? Speculation was a sport in bad years.

Elellanor understood risk—trained on the arithmetic of lineage and property.

She’d learned, too, how fear warps the soul when no one will catch you if you fall.

Her sons: Thomas, twenty-six, strict enough in the fields to render overseers unnecessary.

Mouth a straight line, eyes his father’s, cool, assessing—no visible pain at Henry’s death.

Andrew, three years younger, sent to a small northern college, returned with books, opinions, and the habit of looking directly at things people preferred not to see.

He understood the whip of statute turning, even if men in power pretended otherwise.

Samuel, nineteen, lived in their shadow—quick laughter, quicker temper, too much drink, flirting with town girls who never quite took him seriously, watching his brothers like a hungry dog watches a closed door.

Elellanor loved them by planning their survival.

Every marriage prospect came with conditions cutting land into smaller pieces—a dowry tracked as enticement, fathers in black coats with calculating eyes.

She had kept Witcom land from Henry’s gambling debts only to see it parceled in ruffles and lace.

In her journals, she reasoned without accusing herself.

We breed cattle, horses, hounds openly.

We speak more quietly of human bloodlines and pretend there is no connection.

I am too old for pretending.

Then, in a different ink: If the law refuses to call a thing a marriage unless it is between those of our race, it is because they fear that if they named what we do, God would be obliged to answer.

She spoke with a town doctor—not a plantation sawbones but a man who had read European texts on inheritance—who believed traits could be encouraged in human offspring as carefully as in horses.

You cannot change blood, he told her, but you can encourage its best expressions.

And if the root is weak? she asked.

Then you graft, he said, laughing, sure a woman could not disturb the order of the world.

She went home with that word lodged in her head: graft.

Her entries grew jagged.

Shorter.

Irregular hours.

Words crossed where she changed her mind then changed it back.

The idea coalesced slowly, like mold on jam.

Marrying her sons to white women meant division.

Not marrying meant contest, cousins and creditors picking the bones.

But the law of 1844 left a shadowy space where men of her sort did things and did not call them by their names.

A slave’s child belonged to the master, regardless of father.

No division, no dowry—just more bodies to work or sell.

If such a child shared Witcom blood, the law would not call it heir, but flesh is flesh.

Her sons would feel the land as theirs if children wore pieces of their faces.

Monstrous, she knew.

I recognize that this plan crawls, she wrote, but it crawls toward survival.

Which sin is greater—to let my sons sink into poverty alongside those already shackled, or to use what this cruel world has placed in my hands so we might all remain afloat? There is no answer that is not a condemnation.

She proceeded.

The woman’s name was Laya.

On paper, a line in a bill of sale: female approximately 20 years, sound limbs, good breeding stock.

From three counties away, a plantation failed more spectacularly than Henry’s.

The auctioneer noted proven fertility.

No one recorded the proof’s circumstances.

The midwife at Witcom—records call her Aunt Dina—remembered Laya from another place.

She done tried to break herself, Dina said.

Drank what she shouldn’t, starved herself, threw herself down.

They ain’t like that when they happy.

They like that when they been made into something they don’t want to be.

Elellanor listened, lips pressed thin.

On another page: I understand horses that kick when you put them into the traces.

It does not mean they are not fit to pull.

Laya arrived on a wet spring night, wagon wheels slipping in mud, overseer handing the bill of sale and rope like a chair.

She stepped down, wrists bound, back straight.

In lantern light: narrow face, high cheekbones, eyes brown so dark they were almost black; a jagged scar from the inside of her left wrist up into her sleeve—a blade or broken glass.

You Mrs.

Witcom? she asked, coastal edge in her voice.

Address me as mistress, Elellanor said, and you will not speak unless spoken to.

Something flickered in Laya’s eyes—not defiance so much as a thought sliding behind bone.

Yes, mistress.

Dina watched, smoothing her apron.

Take her to the big house, Elellanor said.

She will not be put in the quarters.

A stir, though no one dared voice it.

A slave woman housed in the main house without role—rare enough to feed the whispers.

Thomas watched from the verandah, arms folded.

Andrew stood half-hidden behind a curtain.

Samuel leaned over the railing, curious.

Another mouth to feed, he said.

Another pair of hands to work, Thomas corrected.

Andrew’s eyes followed Laya’s steps, her bound wrists, her steady footing.

That night, Elellanor summoned her sons to the study.

The Bible sat in the center; a small cedar box held a lock of Henry’s hair cut at burial.

Your father built this, she said, voice steady.

I kept it standing when his habits would have toppled it.

Laws and markets change.

You are men grown.

I will not watch you squander what has been paid with my patience.

You’ve refused every match, she continued.

You talk of freedom and choice like coin in our pockets.

They are not.

We have land, labor, blood.

We must use those.

Andrew shifted, uncomfortable with ceremony.

Samuel lounged, attentive.

Thomas stood balanced, awaiting instruction.

I have decided, Elellanor said.

You will not marry.

Not in society’s eyes.

No gowns, no dowries, no ceremonies that cut this land into pieces.

You will not give some other man’s daughter power to break what your father built.

And we are to live and die alone? Andrew asked, tremor in his voice.

You will not live alone, she said.

Nor die so.

She opened the door.

Dina entered with Laya.

Her hands were free now, but held close to her body.

The dress fit poorly—the way new clothes do when the body inside is not used to being considered.

This woman belongs to this house, Elellanor said.

The law will not call what I am about to arrange a marriage, but I say it is more honest than half the marriages I have seen.

From this day, Laya will be the wife of this family.

She will bear children.

Those children will carry our blood.

They will work this land and inherit it in all but name.

You three will share her as you share this house.

The words fell like stones into a well.

Samuel laughed, incredulous.

I am not asking for understanding, Elellanor cut in.

Only obedience.

You cannot do this, Andrew murmured.

The law cannot stop me, she said.

You know that better than anyone.

Thomas’s dryness: You want us to share a bed as we share a roof.

I want you to remember you are brothers, not rivals, Elellanor said.

The first betrayal in any house is when brothers think themselves men alone.

She placed her hand on the Bible, the lock of hair beside it.

Place your hands here, she said.

Thomas laid his palm.

Andrew hesitated, then placed his hand.

Samuel followed, fingers light, ready to snatch away.

Elellanor’s parchment-dry hand pressed atop theirs.

You swear you will keep your bodies within this house, your seed within this woman, your loyalties within this family.

You will not take wives who demand pieces of this land.

You will not fall in love where love would weaken this agreement.

You swear it before God.

I swear, Thomas said.

Andrew’s throat worked.

I swear, he whispered.

Samuel looked at Laya’s unreadable face.

I swear, he muttered.

Then let heaven hear, Elellanor said, closing the Bible with a soft thump that sounded like a coffin lid.

She turned to Laya.

This house is your master.

These men and no other will come to your bed.

You will not choose among them.

You will not set one above another.

You will bear children and raise them to know their place.

You will not leave this property.

Do you understand?

Laya’s eyes flicked over the brothers, back to Elellanor.

I understand what you say, she replied.

Do you agree? Elellanor demanded.

Silence stretched thin and taut.

What you call agreement, mistress, Laya said at last, is not something you require from me.

Dangerous words.

Samuel’s eyes widened.

Andrew breathed in.

Thomas’s hands curled.

Elellanor smiled a thin, hard smile.

You will find the world rarely requires agreement from the likes of you.

It requires endurance.

You will provide that.

Dina took Laya away to an upstairs room stripped of finer furniture.

The brothers stood like men who had stood too close to lightning.

That was madness, Andrew said hoarsely.

Necessity, Thomas countered.

An abomination, Andrew shot back.

You think the world is clean? Thomas bristled.

Every plantation is built on what you’re suddenly too delicate to name.

Knowing that does not make it right, Andrew whispered.

Right is whatever keeps the roof over our heads, Thomas said bitterly.

Samuel stared at the floorboards, swallowing the vow like bad liquor.

Night changed quality after Laya moved upstairs, air drawn tight like a string.

The first night, Thomas went up, floorboards creaking.

Andrew sat at his desk pretending to read, each scrape tightening his shoulders.

Samuel lay awake, counting the muffled opening and closing of a door.

None spoke of it the next day.

Avoidance doesn’t hold in a house.

Paths cross.

In the library a week later, Andrew found Laya alone, watching boys split kindling.

Morning light caught the angle of her jaw, the hollow at her throat.

Do you read? he asked, because silence felt like complicity.

A little, she said.

He handed her a sermons volume, pointed to a line.

Tell me what this says.

The wages of sin is death, she whispered.

You read more than a little, he said.

Words are no good to you at the bottom of the sea, she replied.

But they feel good in the mouth before you drown.

A girl taught her, she said—stealing lessons from a mistress’s children until they sold her south.

Too clever by half, they said.

He imagined stolen letters passed hand to hand, and it made his chest ache in ways not reducible to desire.

I’m sorry, he said, useless words.

Don’t be sorry, she said.

Be different.

How? Your mother made you swear, she said.

I did not want— But you spoke the words, she said.

Yes.

Then that’s what you live with.

And that’s what I live under.

He gave her books no one read.

She read slowly, lips moving, then argued the lines.

It wasn’t romance.

Not at first.

It was recognition.

Thomas noticed.

He cornered Andrew in the barn, dust thick in the air.

You’re sentimental about property, he said.

She is a person, Andrew said.

She is an asset, Thomas countered.

She is both, Andrew replied.

The law recognizes only one.

That’s not an argument I respect.

This place runs on cotton and discipline, Thomas said.

Discipline is the name you give the violence that keeps your office tidy, Andrew answered.

Careful, Thomas said.

You endanger more than your own soul with your softness.

Maybe I’m trying to salvage something of mine, Andrew said.

Then keep your salvaging to yourself.

Samuel wandered between bravado and unease, visiting Laya at odd hours, sometimes drunk, sometimes needy, talking more than touching.

You’re lucky, he said once, sweat cooling on his skin.

You don’t have to decide nothing.

You do what you’re told, and if it goes wrong, nobody expects better.

I have had decisions, Laya said.

They were between different kinds of wrong.

Summer waned.

Laya missed her courses.

Dina confirmed in the dim room where she laid out the dead and tended the newly born.

Baby’s coming, she said.

Not yet, but coming.

Whose it is don’t matter, Dina went on.

Once he’s here, he’s owned by this house, same as you.

But decide what you mean to do with the little time you got.

What can I do? Laya asked.

Live, or try something else, Dina said.

You already tried breaking yourself.

It didn’t take.

Maybe the Lord means you to hold on.

Maybe he means you to break something else.

When Elellanor heard of the pregnancy, she smiled the smile neighbors call maternal pride.

In her journal, she wrote proof—her monstrous arithmetic yielding desired sums.

Flesh acknowledges flesh.

The law may refuse, but no man can look upon his image and pretend it’s not his concern.

No one knew whose child.

Each brother had visited Laya before her courses stopped; each carried a sliver of uncertainty.

Thomas felt grim satisfaction mixed with resentment, Andrew suffered quietly, Samuel boasted then feared.

Under a live oak, Andrew said, You shouldn’t stand in this heat.

You going to give me a chair? Or a better life? she asked.

If I could give you the second, do you think I would not? Wanting and doing are different, Master Andrew, she said, the title bitter.

Then what are you going to do? He swallowed his growing answer.

I could get you away.

A freight wagon in three weeks.

People in the city.

Who will take a runaway with a baby and no papers? Freedom doesn’t wait at the road’s edge, arms open.

Whatever waits cannot be worse than this, he said.

You’re wrong, she said softly.

It can always be worse.

But different—different might be worth something.

He stepped closer.

I’m not asking you to trust me.

I haven’t earned it.

But I cannot watch my mother’s madness consume you completely.

Let me try to open a door.

They’ll kill you, she said.

Your brothers.

Your mama.

Men in town who nod to you now.

They’ll throw you in the mud next to me.

Perhaps I belong there, he said.

If that’s the price for trying to be something else.

She searched his face.

Get me a way.

A real way.

Maybe I’ll walk through.

Samuel, wandering, heard scraps: They’ll kill you.

Maybe I’ll walk through.

Price for trying to be something other.

Jealousy rearranged fragments into a lie that felt true: Andrew wanted Laya for himself.

Andrew would take her away and keep her where Samuel could never reach.

Dangerous lies are built of misarranged truths.

Elellanor’s entries grew terse.

Heaven watches, she wrote.

Men mutter, but they will envy what I have wrought.

She kept a ledger not only of cotton but of Laya’s condition—days since last course, belly measurements, appetite—like a breeding book.

She instituted a schedule: each son to mark nights visiting Laya in a little book.

Order, she said, against rivalry.

Thomas complied for order.

Samuel complied for attention.

Andrew complied for a time, partitioning conscience from complicity—the man who climbed the stairs because the vow demanded it, and the man who plotted to free her.

Such partitions leak.

Laya hoarded small things—snatches of conversation, wagon routes, trembling in Elellanor’s hands.

Dina watched with weary patience.

You can’t build nothing good on a vow like that, she said.

That ain’t no marriage.

That’s a curse.

Then let it curse the ones that spoke it, Laya said.

I got enough curses on me already.

The night the curse broke came with lightning.

Thunder rolled from the west as sun went down.

Air thick enough to chew.

In the kitchen, pots boiled, servants hurried before the storm took the light.

In the quarters, prayers muttered against leaks and wind.

In the main house, Elellanor hosted the bank’s man with new terms disguised as threats.

Credit has limits, he said.

The war changed many things.

Reduce labor costs or sell acreage.

I will not sell, she said.

Then leave it to those who can.

After he left, she pressed the pen so hard the nib tore paper.

They will not have this house.

She looked at the Bible.

You will hold, she murmured.

You will not break.

Upstairs, Laya felt true pains, iron bands tightening and radiating forward.

Dina said, Baby’s coming.

Storm or no storm, little one don’t wait on weather.

Downstairs, Andrew spread a map.

Wagon route to the depot, then the city.

A man in town—tired eyes, quiet words—had hinted at a network.

Three nights, maybe four.

Keep her hidden and moving to a river contact.

If you’re caught—the sentence didn’t need finishing.

Andrew folded the map, fingers trembling at necessary fear.

Lantern in hand, he headed for the back stairs.

Samuel, restless and drunk, saw him slip toward the rear.

It was Samuel’s night by schedule.

He’d marked it possessively.

Andrew’s urgency looked like sneaking.

Unfairness stacked atop a lifetime of feeling like the leftover lit him.

He found his mother.

Andrew is going to take her, he blurted.

Steal Laya and the baby.

Sell them or keep them.

He thinks he’s better.

He’s breaking the vow.

Lightning rattled glass.

Elellanor’s face went still.

You are drunk, she said.

I’m telling you what I know, he insisted.

He’s up the back stairs on a night not his.

Ask yourself why.

She stood, years falling away.

Where is your brother? Back stairs.

He’ll go to her room.

Find Thomas, she said.

Arm yourself.

She took Henry’s pistol from the cabinet, checked the priming, and followed Andrew’s path with the tread of consequence.

Samuel found Thomas on the covered porch, watching the storm.

They’re going to steal her, Samuel panted.

Andrew and Laya, with the baby.

I heard them.

Wagons.

Doors.

Price.

He’s gone up tonight when it isn’t his.

Then a vow is about to be broken, Thomas said, taking a rifle.

Upstairs, pains surged.

Breathe, Dina urged.

Hold and push.

Blood scented the room, rain smell through the open window.

Andrew knocked.

It’s me.

Let me in.

He slipped inside, hair damp, shirt clinging.

It started, he said.

Seems so, Laya grunted.

He moved to the bedside, unsure—hands hovering.

The wagon is in the barn, he whispered.

The driver can delay an hour.

Room for two under tarps.

Two? Dina’s eyes were knives.

That woman ain’t two no more.

I know, Andrew said.

But once the baby— You’ll kill her and the babe both, Dina snapped.

We stay, he hissed, and they’ll own them both until they die.

I have money.

Enough to get you to the city.

After that—no promises, only something other than this.

Laya squeezed his hand, knuckles white.

You ready to walk the other road with me? Ready for your mama to call you worse than the slaves you trying to save? Your brothers to spit your name? Lose every bit of that pretty standing? Yes, he said.

Then we try, she said.

For once, we break something other than me.

Their foreheads nearly touched—absurdly like lovers—when the door flew open.

Elellanor stood there, pistol in hand.

Thomas and Samuel loomed behind her.

Thunder rolled like accusation.

What is this, she said, voice cold as a cellar, if not betrayal?

Andrew straightened.

Mother— Don’t call me that, she snapped.

You stand in the bed I designated for this house’s salvation, conspiring like a thief, and dare that word?

You will not love any woman more than survival, she said.

You swore it.

And you swore, he said steadily, to keep us whole.

Look what you have done.

You turned us into men who schedule visits to a woman’s bed like appointments with a merchant.

You mocked marriage, kinship, and God’s design.

God has nothing to do with this, she said.

This is blood and land—the only things that last.

The only things you’re going to lose anyway, he said, because you cannot imagine any life but the one handed to you like a whip.

Shut up, Thomas barked.

Samuel’s jaw worked.

Tell her your plan.

The wagon.

Tell her how you thought you were better.

I was planning to get her out, Andrew said.

Out, Elellanor repeated.

Out of this house, out of this life, away from your scheme that binds her body and our souls.

Thunder crashed.

You break this oath, she whispered.

You break this family.

Maybe it needs breaking, he said.

Thomas raised the rifle.

You think you can take something that belongs to all of us? She is not a thing, Andrew said through his teeth.

If any virtue remains, it will be measured by how we treat those we have power over.

The only ones you got power over is yourselves, Dina muttered.

And look how that’s going.

Enough, Elellanor shouted.

We will not let years of work be undone by a boy’s conscience.

She raised the pistol.

What happened next lives confused even in the ink of those present.

Everyone shouted.

Lightning cracked.

Thomas lunged to push the pistol aside.

Samuel grabbed for Thomas’s rifle.

Andrew stepped toward Elellanor, hands up.

The pistol discharged—flat, brutal punctuation in the storm’s tirade.

Gunpowder, sweat, blood, rain.

Andrew gasped, clutching his side.

Blood blossomed between his fingers.

Laya screamed—not from fear but contraction.

Her body cared only for the ancient, terrible work of forcing new life into the world.

Dina sprang.

You two fools out if you ain’t here to help.

He’s shot.

She’s birthing.

I got two hands.

Elellanor stared at the pistol, her bleeding son, the bed where her experiment veered into catastrophe.

I didn’t mean— she whispered.

Lightning lit their fear.

Mama, Andrew gasped.

If you ever loved me, let me do this.

Let me take the burden.

Let me bear breaking so no one else has to.

Breaking won’t save us, she said.

Keeping it will kill us, he replied, falling sideways.

Press, Dina ordered, throwing cloth at Thomas.

Hold the wound.

On reflex more than choice, Thomas pressed.

Samuel backed to the wall, eyes wild.

What do we do? Pray and get out of the way, Dina said.

Rain hammered the roof.

Wind howled down the chimney.

Inside, life and death dragged on a rope.

Laya bore down with strength she hadn’t known.

I ain’t doing this just to hand him over to hands with rings, she snarled.

Ain’t me you got to tell, Dina said.

You tell whoever made this mess.

Andrew drifted in and out.

He thought of graves that might someday bear their names, someone reading a sentence years later and piecing cost from silence.

The baby emerged squalling.

Outside, the storm ebbed as if striking a bargain.

It’s a boy, Dina said, holding the wriggling body.

Laya’s tears mixed with sweat.

Let me see him, she whispered.

Dina laid the baby on her chest.

Pale brown skin, lineage crossing lines the law pretended were iron rather than water.

Elellanor stepped, hands shaking.

There, she said, voice breaking.

We are bound now—flesh to flesh.

This house will not fall.

He will keep it standing.

Laya lifted her gaze, meeting ownership with clarity.

You think so? He will work these fields.

His children will work them.

Your line keeps this place alive.

You will have food, shelter, purpose.

It is more than most, Elellanor said.

Laya laughed—glass breaking.

You really think this house stands on his little back? Blood spilled in this room is your mortar? It is the price we pay, Elellanor said.

Then maybe the price needs to be higher, Laya replied.

She looked at Andrew on the floor, face pale and breath shallow.

Thomas’s hands pressed the wound.

Samuel huddled like a boy in a corner.

You ain’t the only one can use a storm, she whispered.

She pushed herself up, still clutching the baby.

Give him to me, Elellanor said, reaching.

No, Laya said.

The word shocked the air.

You will do as— No, Laya said again.

You talk about vows spoken over me.

I ain’t been allowed to swear nothing in this house, but I’m swearing now.

This child ain’t going to be what you made his daddy be.

He ain’t shackled to your scheme like a mule to a plow.

I’ll burn this place down before I let that happen.

You don’t have the power, Elellanor hissed.

I got the law, the guns, nods when I walk by.

Laya’s eyes flashed.

I got something else.

What? Nothing left to lose.

In the end, that’s all any revolution needs.

Trauma doesn’t write straight.

Pages are torn, ink smeared.

Some events repeat in three versions; others live in haunted confession.

Piece it together, and this emerges: a lamp fell.

Oil spilled.

Flame crawled along floorboards, hungry.

Curtains caught.

Downstairs, a servant smelled smoke and shouted.

Wind whipped flames into the dry eaves.

Elellanor faced a choice she’d never imagined—ledgers or flesh.

She tried, as always, to keep everything.

Take him, she told Dina, nodding at the baby.

Get him out to the quarters.

I’ll send word to town.

And her? Dina asked, nodding to Laya.

She goes where he goes, Andrew rasped, surprising them by speaking at all.

Elellanor hesitated.

The baby is the future, she murmured.

So am I, Laya said.

Or ain’t you been saying that all along?

The house shuddered.

Smoke seeped under the door.

Thomas stood torn between his brother and the window.

Samuel scrambled up, coughing.

In that moment, vows and ledgers and hierarchy crashed into simple reality: fire does not care who owns what.

Dina acted.

You two, she snapped at Thomas and Samuel—pick him up.

They obeyed a woman they’d never counted in their schemes, lifting Andrew under the arms.

You, she said to Laya—hold that baby and don’t let go.

I wasn’t planning on dropping him, Laya said.

They pushed into the hall.

Flames licked wallpaper.

Heat pressed their faces.

Twice Thomas nearly lost his grip.

Twice Laya’s knees weakened; she leaned hard on the banister.

On the ground floor, smoke thickened.

Men threw water uselessly at a roof already chewing fire.

They burst out the kitchen door into air tasting marginally clean, ash swirling like black snow.

For a moment they stood—mistress, sons, slave woman, midwife, baby—blinking in nightmare half-light.

The caretaker boy stood among onlookers, wide-eyed, knowing the moment would haunt the place forever.

What now? Samuel gasped.

We get him to the wagon, Andrew whispered.

We go.

You still on that? Thomas snapped.

More than ever, Andrew said.

He turned to Laya.

Go.

Take what you can of me that’s worth carrying.

She understood.

Which way? she demanded.

Round back, Dina said.

Through the trees.

The driver’s a fool, but he ain’t deaf.

He’ll have heard this mess.

Might run the other way.

They moved.

Elellanor cried out, reaching.

You can’t— We can, Laya said.

For once.

Thomas stepped to block, rifle in hand.

Then he saw the house—the only world he’d known—collapsing as a roof beam shrieked and fell.

He saw his mother, smoke-stained and frantic; his youngest brother shaking.

He lowered the gun.

Go then, he said hoarsely.

If you can live with the ruin you leave behind, go.

Ain’t my ruin, Laya said.

Just my chance to get free of it.

She walked away, baby in arms, Dina by her side, Andrew half dragged—held in motion by will that had finally decided to move.

Behind them, Elellanor sank to her knees in the mud.

I held it together, she whispered to the flaming bones.

I did what I had to.

I made them swear.

Why wasn’t that enough? No one answered.

The elements do not argue ethics.

They consume.

The records falter after that.

A doctor’s bill for a gunshot wound during a domestic accident—no note whether the patient lived or died.

A bank ledger marking foreclosure the next spring.

Sold at auction to a man from another county who never reoccupied the house, claiming damage and too many stories.

A baptism record in a church three towns away for a boy with no surname, mother listed as L, sponsored by a benevolent society.

The date fits Dina’s last scrawl: Took the baby north.

Lord watch him.

Laya disappears, then appears in fragments: a Freedmen’s Bureau note about a woman seeking land, a city marriage register years later—to a carpenter whose name I will keep, because some ghosts deserve peace.

The three graves belong to Thomas, Samuel, and Elellanor.

Thomas died of fever in a damp house near town, his hands never again sure what they owned.

Samuel died in a brawl or accident—accounts differ—his last words a jumble about oaths and fire.

Elellanor lived long enough to watch other people’s children play on ground she believed belonged to her blood; buried at last between her sons under stones someone else paid for.

On the middle stone, someone who knew enough to sum it up scratched a sentence: They swore on her.

One broke, all paid.

I stood there, the book closed in my hands, and felt the weight of it—the monstrous inventiveness of cruelty, the contortions of love inside systems designed to crush it, how vows spoken under a rotten roof crack the foundation beneath.

The caretaker—now a man—came up beside me.

You find what you were looking for? he asked.

I found enough, I said.

He nodded at the graves.

Folks say the place is cursed.

Places aren’t cursed, I said.

People are, or they curse themselves.

What about her? he asked.

The slave wife—the one they swore on.

She walked away, I said.

So the records suggest.

He whistled softly.

That so.

Good for her.

Yes, I said.

Good for her.

We stood a while longer as the sky darkened and fireflies stitched stubborn light over the weeds.

If you’ve stayed with me this far—listening to how one woman’s desperation twisted her sons’ lives and tried to bind another woman’s body to a dying house—then you know the question sitting on the middle stone.

When Andrew broke the oath, did it damn him, or save what was left worth saving? Would you have walked into the fire—or into the dark? Sometimes stories matter only when we argue with them out loud, the way Laya loved the angry psalms—words that sound less like bowing and more like speaking back to God.

And if there are more nights like this—ledgers opened, secrets hauled into light, tales from places this country would rather forget—then you know where to find me.

The next time I lift a lantern over a forgotten name in a courthouse file, I’ll be here, ready to see what crawls out of the past with us.

News

Slave Girl Seduced the Governor’s Son — And Made Him Destroy His Father’s Entire Estate

The seduction, they would later say, began in the chandeliered light of a ballroom. But Amara knew it started years…

She Was ‘Unmarriageable’—Her Father Gave Her to the Strongest Slave, North Carolina 1855

The night my father bargained my life away to the man everyone on our plantation called Goliath, the lamplight caught…

A lonely man from Mississippi bought 3 virgin slave girls – what he did with them shocked everyone

The iron bell of the auction house clanged through the humid air of Natchez, Mississippi, on a blistering July afternoon…

The Profane Secret of the Banker’s Wife: Every Night She Retired With 2 Slaves to the Carriage House

In a river city where money is inked but paid in human lives, the banker’s wife lights a different fire…

The Plantation Lady Who Locked Her Husband with the Slaves — The Revenge That Ended the Carters

The night I decided my husband would go to sleep on a slave’s pallet, the air over Carter Plantation felt…

The Pastor’s Wife Admitted Four Women Shared One Slave in Secret — Their Pact Broke the Church, 1848

They found her words in a box that should have turned to dust. The church sat on the roadside like…

End of content

No more pages to load