In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken that would become one of the most unsettling images of the 19th century.

It was meant to capture love and loss, a tender farewell between mother and daughter.

But in time, it would expose a tragedy so haunting that it changed how physicians across the south approach the very notion of death itself.

This is the story of the Whitaker girl.

On the morning of June 21st, 1863, in the quiet sugar farming parish of St.

Martinville, 9-year-old Clara Whitaker failed to wake for breakfast.

The Whiters were a modest family.

Her father, Nathaniel Whitaker, a former riverboat engineer turned farmer, and her mother, Elellaner, known for her gentle voice and chronic frailty.

The Civil War raged hundreds of miles away.

But for the Whiters, life was already steeped in uncertainty and loss.

For three days prior, Clara had suffered from what her mother described as a fever that waxed and Wayne like the moon.

The local physician, Dr.

Byron C.

Halpern, trained at the short-lived Louisiana Medical College in Baton Rouge, diagnosed a nervous inflammation likely intermittent.

His notes, later discovered among his papers at the New Orleans Institute of Pathological Studies, indicate he had recommended rest, camper spirits, and gentle cooling with vinegar cloths.

By Sunday morning, Clara’s fever seemed broken.

She had smiled faintly at her mother and murmured something about wanting to see the sunrise.

When Eleanor returned an hour later with water from the well, she found her daughter lying perfectly still, her hands folded over her chest, her eyes half closed as if in soft repose.

Dr.

Halpern was summoned again.

He rode from town on horseback, arriving just before noon.

His examination was brief.

He held a small mirror to the girl’s mouth, pressed two fingers to her wrist, and listened for a heartbeat with his ear against her chest.

Hearing nothing, he declared with quiet gravity.

She has passed from the fever, “God rest her.” Clara’s skin, he wrote, was not yet cold, but lacking pulse.

He attributed the faint warmth to lingering vital vapors, a term common in mid-century medical vernacular.

He advised immediate interment due to the oppressive heat.

Louisiana’s summer air did not forgive delay.

The Whiters were devastated.

Clara had been their only surviving child.

Two brothers had died in infancy.

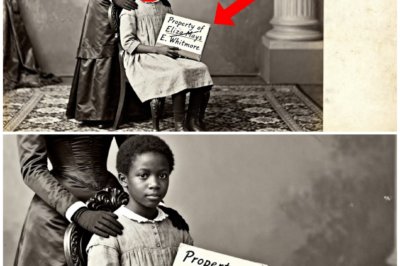

To preserve her image, Eleanor requested a photograph, a momento of her daughter’s peaceful face before the burial.

Post-mortem photography had by then become a common ritual, spreading from England to America through the new Dgeray and wet collodian processes.

The town’s photographer, Mr.

Isaac Penrose, arrived the next morning with his heavy tripod and a satchel of glass plates wrapped in oil cloth.

Clara’s small body was dressed in her Sunday gown, pale blue with a lace collar.

Her mother brushed her hair, placing a ribbon above the left ear.

Penrose arranged her in an upright pose on the family set near the parlor window, where the morning light fell softly through the shutters.

Elellaner, trembling, sat beside her daughter, one hand lightly touching Clara’s own.

In his later writings, preserved in a faded notebook now held at the Acadiana Museum of Historical Photography, Penrose described the sitting, “The child’s lips retained a hue too lively for death.

The mother wept throughout, and I twice paused, for the image of the eyes seemed to alter under the light.

When the plate was developed, the result was eerily lielike.” Clara’s cheeks bore a faint flush, her mouth curved with what could almost be mistaken for a breath.

The photograph became known locally as the sleeping child, a tender relic of mourning.

She was buried that evening in the small churchyard of St.

Martin’s Chapel beside a field of wild magnolia.

Her coffin, built from cypress boards and sealed with tar, was lowered as cicas droned, and the first stars appeared in the humid dusk.

In the weeks that followed, Eleanor Whitaker was seldom seen outside.

Neighbors recalled hearing her at night, softly humming lullabies to the photograph on her mantle.

Nathaniel returned to the river trade, leaving her often alone in the quiet, empty house.

Life drifted on the way it always does after loss, slowly, unevenly, as though the air itself carries the weight of memory.

Nearly 55 years later, in 1918, the town of St.

Martinville was struck by severe flooding from the Bayutesh.

Whole sections of the old cemetery were submerged and many graves were disinterred for rearial on higher ground.

Among those exumed was the coffin of Clara Whitaker.

The excavation was overseen by Dr.

Edwin Marin, a forensic examiner from the University of Lafayette Medical Faculty, who had been dispatched by the state to supervise the relocations and document any historical remains.

When workers pried open the Whitaker coffin, they were stunned by what they found.

The interior of the cypress wood was clawed and splintered.

The skeleton, small and fragile, was twisted to one side.

The arms bent violently upward, fingers spled against the lid.

Several ribs were broken inward, and fragments of coffin wood were found beneath the fingernails.

Dr.

Marin’s report dated August 2nd, 1918, now archived in the Louisiana State Medical Records repository, reads, “The position of the remains in the extensive damage to the interior surface indicate unmistakable signs of voluntary struggle after burial.

It is the examiner’s opinion that the subject, a juvenile female approximately 9 years of age, was interred in a state of suspended animation or apparent death rather than true demise.

Local newspapers soon sees the story.

The Lafayette Herald printed a front page article under the headline, “Child buried alive in 1863, horrors of a century unearthed.” The revelation spread quickly.

Scholars and journalists descended upon St.

Martinville, demanding to see the photograph, the same sleeping child image that had hung for decades in the Whitaker home.

Clara’s descendants, now living in Baton Rouge, reluctantly provided it.

When examined by specialists at the Two Lane School of Medical Photography, the plate revealed what earlier viewers had dismissed.

The faintest sign of moisture on the lower lip, slight tension at the jawline, and most disturbingly, an almost imperceptible glint in the left eye, consistent, some claimed, with the reflection of light upon a corial film that had not yet clouded.

Dr.

Marin’s team concluded that Clara had likely suffered from catalyptic trance, a condition now recognized as a rare form of hysterical or epileptic coma, during which the body appears lifeless, though vital signs persist.

In the sweltering heat of a Louisiana summer, her shallow breathing and faint pulse would have been easily missed.

Modern analysis later suggested that the girl may have regained consciousness 2 to three hours after interment.

Trapped in utter darkness, her cries muffled by earth and wood.

The very thought chilled even hardened doctors.

Marin’s assistant, Dr.

Louise Garvey, one of the first female pathologists in the region, wrote privately in her notes.

I have held the bones of a child who awoke to her own burial.

May heaven forgive those who failed to see her breath.

In the months following the discovery, Clara’s photograph became the centerpiece of medical lectures across the South.

The Louisiana Journal of Neuropathology published an article titled The Whitaker Case and the Physiology of Apparent Death.

It compared her ordeal to earlier European accounts, including the 1854 Lion Catalpsy Incident and the infamous Wexler case of 1849 in Pennsylvania.

The findings fueled public fear of premature burial.

Coffin makers began advertising safety interment devices equipped with small air tubes and bells.

In New Orleans, an inventor named George Huvelman even patented a burial signaling apparatus.

A cord attached to the wrist of the deceased, capable of ringing a bell above ground.

Few were ever used, but the notion that death itself might be fallible, spread like wildfire.

Eleanor Whitaker never lived to see the truth revealed.

She died in 1891.

her mind clouded by grief and illness.

Neighbors said she would often sit by the window clutching the faded photograph, whispering, “She looks so alive.” When her letters were discovered in a trunk decades later, one contained a chilling passage.

I dreamed I heard scratching from the earth that night.

I woke Nathaniel, but he told me it was the wind through the cane.

After the 1918 discovery, the remains of Clara Whitaker were placed in a new coffin, lined in silk, and re-eried with proper rights in a raised vault near the chapel wall.

A bronze plaque was added above her name, reading simply, “May her sleep now be true.” By the 1930s, the Whitaker photograph had become a subject of fascination among historians and psychologists alike.

At the University of Georgia’s Department of Thanottology, scholars debated whether the image represented not only a tragedy, but an artistic document of the human threshold between life and death.

Professor Elias Norwood, writing in 1937, remarked, “The Whitaker portrait is less a photograph than a confession, a confession of medicine’s ignorance and man’s terror of uncertainty.

In that child’s stillness resides the greatest question our science has yet to answer.

When precisely does life end? The photograph was exhibited in 1952 at the Smithsonian’s morning and memory collection where it drew record attendance.

Viewers reported feeling an almost living presence in the image.

An uncanny warmth in the eyes that seemed to defy the cold logic of death.

To this day, the original plate remains in the Louisiana State Archive of Historical Medicine, restored and preserved under low light.

Archivists say visitors sometimes claim to see condensation appear briefly on the inside of the glass like a breath fogging a window.

No scientific explanation has been offered.

Historians continue to debate the Whitaker case.

Some argue that soil compression or coffin collapse might account for the displaced bones.

Others believe the evidence of claw marks and broken falling is too deliberate to be dismissed as post-mortem distortion.

Neurologists studying historical catalpsy cases cite the Whitaker tragedy as a key example of why early diagnostic criteria were so unreliable.

Without stethoscopes sensitive enough to detect faint cardiac activity or instruments to measure brain waves, 19th century doctors often declared death based solely on visual cues, palar, stillness, and lack of respiration.

Even Dr.

Halpern’s later students at the Louisiana Medical College noted that he had written a remorseful addendum to his 1863 case book dated years after the fact.

Had I known the subtleties of nervous torper, I might have hesitated, but knowledge comes too late for the lost.

No one knows what became of the Whitaker family line.

Records suggest that a distant cousin, Eleanor Ruth Whitaker, donated the original photograph to the state archive in 1948 along with the family Bible.

Inside the Bible’s front page, written in faded ink, are the words, “She sleeps beneath the Magnolia.” Her eyes were never truly closed.

The Whitaker tragedy stands today as a haunting symbol of human error and the perilous thinness of the boundary between life and death.

It reminds us that compassion and science must always walk hand in hand and that even the most ordinary photograph can conceal the weight of unimaginable horror.

When visitors to the museum pause before Clara’s image, they often remark on how peaceful it seems.

How the small girl appears merely asleep, lost in some innocent dream.

But those who know the story understand that within that stillness lies something far more terrible.

the echo of a breath unheard, a heartbeat unseen, a desperate scratching beneath the soil of time.

So the next time you see a faded Victorian portrait, with its glassy eyes and solemn calm, remember this story.

Remember that in the age before certainty, some who were mourned might still have been alive.

And if tales like this one, stories buried in the forgotten corners of history, fascinate you, don’t forget to like this video, subscribe to the channel, and join us as we uncover more mysteries where medicine, death, and the human heart intertwine.

Because sometimes the quietest photographs tell the loudest truths.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

This 1868 Portrait of a Teacher and Girl Looks Proud Until You See The Bookplate

This 1858 studio portrait looks elegant until you notice the shadow. It arrived at the Louisiana Historical Collection in a…

End of content

No more pages to load