In the winter of 1844, the slave market at the edge of New Orleans smelled of molasses, sweat, and a sour note that clung to the throat like a secret no one wanted to admit.

Broadcloth men in beaver hats moved through the aisles with the confident boredom of those born convinced the world belonged to them.

Auctioneers sang numbers and names.

Chains answered with dull music.

Riverboats ground upriver.

Gulls cried overhead.

The place had a rhythm.

It was the rhythm of buying and selling lives.

Into that racket walked a young widow in black.

A veil shadowed her face.

A velvet purse gloved in her hand.

Marabel Ashford stepped carefully, as if every board on the raised platform were a stage she had no wish to stand upon.

Yet there she was—virgin widow of Ashford Reach, the woman parlor whispers had wrapped in rumor.

A strange cold union, they said.

A husband dead without leaving an heir.

A marriage never consummated.

She felt their eyes before their voices carried: Is that a woman’s voice? It can’t be.

Not here.

Not her.

Harland Coste, the yard operator, saw her approach the block.

His face rearranged itself into confusion under a courteous mask.

“Mrs.

Ashford,” he said, dipping his head, wary more than respectful.

“Didn’t expect to see you in a place like this.

If you’re looking for house help, I can have the girls—”

“I’m not here for a girl,” Marabel said, steady behind the veil.

“I’m here for a man.”

Noise dimmed around them.

Men inspecting teeth and shoulders glanced over.

A widow buying a male slave was not extraordinary.

This widow doing so openly was spectacle.

“We have strong field hands coming after the carthorses,” Coste managed.

“If you’ll take a seat—”

“I’m not here for a field hand either.” Her gloved fingers tightened around the purse.

“I’m here for a particular man.” She paused.

“His name is Lazarus.”

Coste’s eyes flickered.

He disciplined his expression.

Lazarus was not a name that made it onto broad sheets.

He wasn’t paraded at high noon.

Lazarus was margins, not ledgers—whispered in back rooms, associated with a commodity respectable people pretended not to know existed.

“I’m afraid I don’t know—”

“Do not lie to me, Mr.

Coste,” Marabel said quietly.

“My husband dealt with you for years.

I have seen his books.”

It wasn’t strictly true.

Victor Ashford had kept his main plantation ledgers locked.

After his death, Marabel had pried loose a board in his study wall and found the book he had hidden.

Not cotton yields.

Not barrel counts.

A colder calculus: bodies cataloged by hips and shoulders, height and bone, flesh tabulated for breeding.

Men with a small letter beside their names—Breeder.

Some crossed out: dull, wastes seed, unreliable.

One had no edits, only Victor’s mark reserved for something rare and flawless.

Lazarus—$2,000—proven—do not lose.

Coste studied her, weighing profit against risk.

“That ain’t a name we use in public trade,” he said slowly.

“I am not the public,” she replied.

“And I have $2,000 to say you do have him.”

The number moved through the crowd like wind in reeds.

Two thousand.

Most men had never paid so much for a single human being.

Two thousand could buy a family, a dozen field hands, a small city house.

To offer it for one man meant he was not being purchased simply to swing a hoe.

Faces turned more openly.

Curiosity sharpened.

So that’s how the virgin widow means to stop being a virgin, someone murmured, and laughter spread oily and thin.

Coste hesitated, then gestured to a runner.

“Fetch the special lot from the back.

Chain room three.

Tell him we got a buyer.”

“Mrs.

Ashford,” Coste said, turning back to her, voice lower.

“You understand the type of property you’re asking for.

These men ain’t standard stock.

Papers are sensitive.”

“I understand perfectly,” she lied.

“The money is in my carriage.

Your man can count it there.

I’ll wait.”

She took a step back as the auctioneer called another lot.

A woman with two small children was hauled onto the block, hair mussed, eyes wide.

Bids began, voices bored and brisk.

Marabel’s stomach clenched.

She turned away.

In her life, markets had been account-book abstractions.

Victor had said this was no sight for a lady.

Perhaps the only point where she had ever agreed with him.

Yet here she stood, among shouts and iron and human ruin, because of a ledger he hid and a note she found scrawled in code beside her own name: M—untested—reserved for special breeding—discuss with S.G.

She knew those initials.

Silas Gley of the New Orleans Mercantile Bank—Victor’s favorite creditor, smiling banker with ledger ink on his fingers.

The sound of chains preceded him.

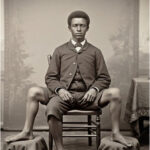

The runner returned with keys and walked in front of a tall shackled man flanked by two guards.

Even before his face was clear, his shadow fell across the planks broad and steady.

His back was straight despite iron.

He wore no shirt, only rough trousers tied with frayed cord.

Iron around his wrists caught light—and so did faint scar threads crossing his forearms like pale vines.

His features were sternly symmetrical, not delicate.

His eyes were a deep, steady brown—too intent for someone supposed to be livestock.

Marabel’s breath hitched behind her veil.

She had never seen him, yet she recognized the shape of him from Victor’s ledger sketches—little pencil silhouettes with measurements, chest, height, weight, progeny notes.

“Brought as requested,” Coste said.

“Lazarus.

Papers match.”

The man looked at her, the veil, the black dress.

Confusion flickered.

Curiosity.

A weary amusement at the sight of the person who bought him for $2,000 being small framed and young, gloved hand clamped like a drowning person’s grip.

He tipped his head barely, an acknowledgment—recognition that she had called him by name.

They brought him to a side platform, not the main block.

There would be no bidding—only a private sale dressed in the costume of auction.

“The price you mentioned is accurate for previous quotations,” Coste said.

“Given passage of time and current market—”

“Two thousand,” Marabel repeated.

“As agreed.

Counting here would be unseemly.

Your man may come to my carriage.”

Coste licked his lips.

He likely never imagined bargaining decorum with a woman over a breeder slave.

“Very well,” he said.

“We’ll need signatures.

This property is registered under a special class.”

Special class.

Men whose worth was measured not in acres plowed but in children generated from other men’s marriages.

Marabel’s fingers trembled, then obeyed her will.

When the transaction was done, money counted, paper signed, Lazarus was led to her carriage in a small procession of eyes and whispers.

Mrs.

Ashford.

So that’s how she plans to solve it.

Let them think they knew.

The truth was worse.

Lazarus ducked inside.

Chains on his wrists clinked softly.

Even sitting, he shrank the interior by his presence.

He smelled of iron and sweat and a faint medicinal salve.

The carriage jolted.

Cobblestones gave way to packed dirt.

Shouts faded.

The air cooled.

“You paid too much,” Lazarus said finally.

His voice was low, rough, not grateful, not defiant—a fact stated.

“No man is worth that.”

“My husband thought otherwise,” Marabel said.

“Victor Ashford is dead,” Lazarus said.

“Yes.” Her hands curled on her lap.

“His debts are not.”

Something ghosted his mouth—almost a smile.

“Then we share a misfortune, ma’am.

Your debts are coin.

Mine are flesh.”

“Lazarus,” she said.

He looked properly now, curiosity sharper.

“How many children,” she asked, “have you been forced to sire?”

The question changed the air.

His jaw tightened.

Chain brushed iron as his hands closed.

“You ask plain for a lady,” he said.

“I’ve spent two months reading a book that burned the word breeder into my eyes,” she answered.

“Plain is all that’s left.”

He searched her face for mockery and found none.

He looked out the carriage window at cypress sliding past.

“I don’t know the number,” he said at last.

“Sometimes they told me.

Sometimes they didn’t.

Dozens.

Maybe more.”

“Why?” she asked.

“Because,” she said quietly, “my husband had a plan to make me part of that number, and I don’t know why he stopped.”

Birds startled from a bare tree, black against gray sky.

Lazarus looked back at the woman who bought him for $2,000.

For the first time, interest—real interest, not survival’s calculation—lit his eyes.

“What do you want from me, Mrs.

Ashford?” he asked.

“My body or my memory?”

“Both,” she said.

“But not the way you think.”

Ashford Reach rose from mist like a fever memory.

The big house sat on a low rise over dull season sugarcane.

Columns stained gray by weather.

Moss-draped oaks lined the drive.

Smoke from quarters drifted upward in resigned threads.

As the carriage rolled in, heads turned.

Chains glinting drew widened eyes and murmurs.

Miss Marabel’s brought back a bull, someone whispered.

She’s really going to do it, someone else said.

Jonah, the butler—a free Black man long more loyal to the house than to the man who owned it—stepped forward.

His gaze flicked from Marabel’s veil to Lazarus’s wrists and back.

His lips thinned.

“Please see he’s quartered in the north outbuilding,” Marabel said, stepping down.

“I’ll speak with him later.”

“Yes, ma’am,” Jonah said.

Men took Lazarus’s chains.

He allowed himself to be led—posture controlled, neither submissive nor challenging.

As he passed Jonah, their eyes met briefly—recognition not just of strength but of a man who had learned where pain came from and how to meet it.

Inside, the hall smelled of beeswax, old wood, cigar ghosts.

Victor’s boots still sat polished by the door.

The silence he left held a shape, as if he might step in and ask why she looked pale.

Marabel went straight to his study.

She pried the board loose.

From the hollow, she drew the hidden ledger and laid it beside her own careful copy.

Twin hearts.

One black.

One gray.

Both pulsing with secrets.

On one page, Lazarus’s name appeared in careful script again and again.

Next to entries, brief notes:

March 1839 — G Plantation, St.

James Parish.

Owner: Budro.

Objective: Strength and stock.

Result: one boy, one girl — strong.

July 1840 — V Estate, Plaquemines.

Owner: Vail.

Objective: heir in wedlock.

Result: unknown.

August 1841 — Private house (city).

Owner: SG.

Objective: personal.

Result: undisclosed.

Names and places formed a map.

Each was not only location but dinner table, pew, nursery.

Her own initials appeared elsewhere: M—untested reserve—arrange private consult with SG when terms favorable.

The absence of follow-up both relieved and haunted her.

Why had Victor stopped? Repentance? Forewarning? Or had death interrupted?

She was still staring when Jonah knocked.

He stepped in, shut the door.

“Pardon, ma’am.

I’ve seen to the new man.

North outbuilding.

Water and a bite.

Thought you should know—the talk’s spreading fast.”

“When does talk not spread fast?” she asked tiredly.

“This is different,” Jonah said gently.

“They’re saying you bought yourself a breeder, ma’am.”

Marabel’s hands stiffened.

“What do you say, Jonah?”

He hesitated, eyes dropping to the ledger—long enough for her to see he knew such books existed.

“I say there’s things a woman does to survive a world made by men,” he said.

“And sometimes what looks like sin from the pews is just someone choosing between different kinds of hell.”

She stared.

“Will you judge me for what I do next?”

“Not my place,” he said.

“But I’ll tell you this.

Whatever you do, own it.

Don’t let them pretend you were nothing but someone else’s idea.”

The sentence followed her to the old carriage house.

The north outbuilding smelled of old leather and damp wood.

Light from a high window traced lines on Lazarus’s bare shoulders—old scars mapped like rivers.

The ankle shackle chained to a floor bolt remained.

He looked up as she entered.

“Mrs.

Ashford,” he said.

Not ma’am.

Formal address as person.

“Lazarus,” she said, closing the door on outside noise.

“Are you comfortable?” she asked.

“I’ve known worse,” he said.

“Roof’s a blessing.”

She moved closer and unwrapped her copy of the ledger.

“I didn’t bring you here for what they think.”

“I know.” A tilt of the head.

“Not yet, anyway.”

She flushed under the veil, steadied herself.

“I brought you because my husband kept a book with your name in it.

I think you may be the only person alive who can help me read it properly.”

He eyed the bundle.

“Victor kept many books,” Lazarus said.

“The usual ones—who picked how much, who cost what.

You talking a different kind?”

“Yes,” she said.

“The kind men hide in walls.”

A movement in his expression—recognition and banked anger.

“Bring it here.”

He opened it slowly.

He said nothing for a long time.

His eyes moved with intensity.

His fingertips hovered over names and dates and notes.

His jaw clenched sometimes.

“You can read,” she said softly.

He snorted.

“Men who trade bodies forget we got minds too.

Sometimes they teach us numbers and letters so we can tally their fortunes.

Think it don’t matter if we see what they doing, long as we can’t do nothing.”

His finger landed on his name.

“Here—G Plantation, St.

James.

Veil’s.

SG.

He used to come by Victor’s office.

Smelled like ink and citrus.”

“Silas Gley,” she said.

“My banker.”

“Makes sense,” Lazarus muttered.

He turned a page.

“Quite the choir of righteous men you got scribbled here—planters, judges, preachers.

They all sang pretty Sundays.”

“Tell me,” she said.

“Every house.

Every face.

Every time.”

He looked up sharply.

“Why? So you can feel sorry? Or so you can get what you paid for with less guilt?”

“I bought you because my husband planned to use you on me,” she said, voice shaking.

“Because there’s a note beside my name.

Because the man who holds my debts is in that book.

Because I am tired of being the only one who doesn’t know what’s been done to them.”

Something in her face stripped the words of self-pity and left need.

Lazarus studied her, ledger on his knee.

“You think he stopped?” he asked.

“Think Victor repented?”

“I don’t know,” she whispered.

Lazarus breathed out a weary sigh.

“I’ll tell you what I know,” he said.

“Not because you own me.

Because I’m tired of being the only one who remembers.”

He talked slowly, each word dragged from a place he had nailed shut.

Hot nights and cold rooms.

Long rides with a bag over his head.

Studies and bedrooms where he was treated like a tool taken from a locked trunk.

He did not describe acts in detail.

He did not need to.

Violence lived in the structure, not the motion.

Men with names carved on courthouse pediments discussed breeding strategies over brandy—skulls and bloodlines—while wives wept quietly upstairs.

One gentleman refused to look at him, delegating instructions through a steward—as if seeing would stain him.

Another woman clutched his arm and whispered apologies into his shoulder—as if any apology could reach where harm lived.

He spoke of the Vail estate—of a child with pale eyes and familiar hair running past his legs without knowing from whom height and strength came.

Of Silas Gley’s townhouse—of a thin woman with bruised wrists watching with hollow gaze.

He finished.

Silence filled the room louder than speech.

“And Victor?” she asked.

“What did he—”

“Victor liked to think himself the man who kept the wheel greased,” Lazarus said.

“He didn’t always participate—not that I saw.

He liked to talk theory—bloodlines.

Profit.

Importance.

I heard him say once, ‘We’re making a better South, one improved generation at a time.’”

Once Victor had said something similar at dinner about crop rotation.

Now she knew he had meant both.

“Did he ever speak of me?” she asked.

“One time,” Lazarus said slowly.

“His study.

Gley there.

Victor said ‘wasted womb’—pity to have a young wife with good hips and no issue.

Gley said it was a problem he could solve.

They talked arrangements.

Me.

A sum.

Your name was mentioned.

Later I heard Gley say the deal was postponed.”

“Postponed,” she repeated.

“Not canceled.”

“So it seemed,” Lazarus said.

She breathed against the sickness in her throat.

“What do I do with this?” she asked.

“Dead husband’s ledger.

Banker with my land in his fist.

A man whose name appears next to the faces of half this parish’s heirs.”

“Most folks who know a little keep quiet,” Lazarus said.

“Protect what’s theirs.

Some try blackmail.

Most end up dead or worse.”

“And you?” she asked.

“What do you want?”

He gave a short laugh.

“Want? Stopped using that word long ago.

I need simpler things.

Not to be sold again.

To see men who used me afraid once.

For children they made me bring into this world not to grow up in the same lie.”

“I can’t promise I’ll save everyone,” she said.

“I may not save myself.”

“Maybe not,” Lazarus said.

“You got something I don’t—name, table, rooms.

They taught you to stitch and smile.

Maybe it’s time you cut something open.”

“Do you trust me?” she asked.

“No,” he said simply.

“But I trust you hate being used.

That’s a start.”

Winter deepened.

Advent brought parish to church.

Whites in pews.

Enslaved families listening from the yard.

The sermon was on righteousness and fleshly temptation.

The preacher looked straight at Marabel when he praised widows who kept their bodies temples.

His eldest son sat two pews down—jawline familiar for reasons that had nothing to do with his putative father’s face.

When the plate came, she laid coin on wood and thought of how many sermons had been purchased with silence.

In the yard, Silas Gley approached in black gloves and a smile that didn’t touch his eyes.

“Mrs.

Ashford.

You are a picture of devotion.

I’ll confess—when I heard you went to the market alone, I wondered if it might be the beginning of decline.” His gaze flicked to a cluster of whispering men.

“I see now you remain proper.”

“Appearances can deceive,” she said.

“Indeed,” he said.

“We must be careful what appearances we create.”

He lowered his voice.

“You have taken on a considerable piece of property.

That man Coste sold you is known in certain circles.

Word reaches me—as it does others.

A young widow purchasing such a special investment—” He let implication hover.

“My husband left me in charge,” she said.

“If I wish to buy a mule or a man, that is my prerogative.”

“Up to a point,” Silas said pleasantly.

“There are contracts—obligations.

The bank has an interest in ensuring its collateral is maintained with utmost respectability.”

“Are you threatening me?” she asked.

“Advising,” he said with that patronizing chuckle.

“You are young and inexperienced in certain matters.

It would be a shame if gossip led to questions about your management—questions that might compel the bank to take a more active role in stewardship.”

“Stewardship,” she repeated.

“Is that what you call it when a man chokes a thing so tightly it can barely breathe?”

His genial mask slipped.

“You should have remarried,” he said quietly.

“A woman in your position needs a husband to bear responsibilities.”

“Recommendations I ignored,” she said.

“Perhaps I’ll continue.”

That night, she told Lazarus.

“They’re closing ranks,” he said.

“They smell something.”

“What do they think I’ll do?” she asked.

“Parade you with a banner—Here is the man who fathered half your heirs?”

“A secret is comfortable only in the right hands,” Lazarus said.

“You’re the wrong hands now.”

“If I do nothing, Silas takes the land,” she said.

“If I marry his man, I become a brood mare elsewhere.

If I use you like they used you—” She swallowed.

“Then I become exactly the idea they wrote in that ledger.”

“There’s another way,” he said.

“Harder.

Messy.

Dangerous.”

“Say it.”

“We make them afraid.

Not with guns.

With truth.”

She let out a bitter sound.

“Truth never protected anyone here.”

“Not yet,” he said.

“It’s always spoken by mouths nobody listens to—house girls in kitchens, men like me in chains.

You got the ledger.

You got the name.

You sit at their table.

What if you didn’t talk debt and weather next time?”

“Even if I did,” she said, “what leverage? They’d deny, burn the ledger, silence you.”

“Not if they knew there’s more than one book,” he said.

“More than one witness.

Not if they thought the story travels farther than their reach.”

“How?”

“You heard of abolitionist papers?” he asked.

“Writers up north pay for stories that make southern men look like devils.

There’s a boy at the river runs messages for a printer.

Knows how to get letters on boats that ain’t checked.”

“They’d hang me,” she said.

“Or,” he said, “they’d be scared of rope.

Settle your debts.

Cut you loose quietly.

Long as you keep your mouth shut.”

“And you?”

He shrugged.

“Maybe I end up on a road gang.

Maybe I run.

Maybe I don’t live long.

At least I die doing something other than what they trained me for.”

She stared.

“I’ll need names,” she said.

“Proof beyond this ledger—letters, witnesses.”

“Then we work,” he said.

They did.

Marabel accepted invitations she used to decline.

Afternoons at Augusta Vail’s table.

Evenings at the Whitfield parsonage.

Visits to Silas’s office to “discuss refinancing.” Children who had once blurred into curls and pinafores sharpened into detail: the set of a boy’s shoulders, a girl’s jaw—the way a teenager’s laugh echoed Lazarus’s.

She listened as women loosened by sherry spoke in code about late blessings and unexpected answers to prayer, about husbands who had been ill when sons were conceived.

Men confident in her silence joked about foreign blood strengthening old stock.

She tucked remarks away.

Sometimes she let her gaze linger a heartbeat too long on a child’s face.

Back in the carriage house, she and Lazarus traced routes with fingers.

Each ledger entry grew faces and voices.

“Some weren’t cruel,” Lazarus said once.

“Not to me, anyway.

Some tried kindness.

Gave extra food.

Spoke soft.

Kindness wrapped around a crime is still a crime.”

“Do you hate them?” she asked.

“I hate what they did more than who they were,” he said.

“Don’t make much difference to the children.”

Spring crept.

Rumors grew.

People said the widow received visitors.

That she walked her own rows, asking questions Victor never did.

That she spoke privately with Jonah and the midwife and a boy at the docks.

Silas sharpened.

“You’re overstepping,” he said in his office—sunlight slanting through tall windows onto ledger stacks.

“You speak of disaster as if it’s not already baked into these accounts,” she said, scanning columns.

“Tell me, Mr.

Gley—how many notes belong to men listed in this ledger?” She laid Victor’s book on his desk.

Silas’s composure failed for a second—eyes widened, skin paled, hand darted to slam the cover.

“Where did you get that?”

“From my husband’s walls,” she said.

“Why wasn’t it in your vault?”

“You don’t know what you’re playing with,” he hissed.

“That book contains private—”

“It contains how men like you and my husband treated human beings as livestock,” she said.

“How you nested cruelty inside marriages and pews.

The question isn’t whether I understand.

It’s whether I’ll stay quiet.”

“You’re not the only widow,” he said, standing abruptly.

“Think you can stand against the weight of every name? You’ll be crushed.”

“Perhaps,” she said.

“Perhaps not.

There are people up north who might find names interesting.”

“Traitors,” he spat.

“Fanatics.

You’d align with them?”

“I’d align with any force that gives me leverage against men who wrote my womb into a breeding plan,” she said, fury shaking her.

“Do not talk to me of traitors.”

He stared.

“What do you want?” he demanded.

“Name it.”

“I want Ashford Reach free of your hands,” she said.

“Debts cleared or reduced to what I can pay.

Note on the tobacco farm released.

Manumission papers for names I give you—Lazarus among them.

And I want you to know—if anything happens to me or to him—copies of this ledger and letters bearing your name travel north within the week.”

“You overestimate your power.”

“You overestimate my fear.”

She left with her heart racing and hands trembling.

That evening, she relayed it to Lazarus.

“You stared down the man who owns your paper life,” he said, a flicker of admiration.

“How’s it feel?”

“Terrifying,” she said—and then laughed unexpectedly.

“And like being alive for the first time.”

“He won’t keep his word easy,” Lazarus cautioned.

“Men like that dig loopholes.”

“I know,” she said.

“We make sure he understands what happens if he tries.”

They drafted letters—addressed to a New York printer Lazarus had heard of, and to “friends of the cause” at an abolitionist society.

She wrote in neat hand: a story beginning with a hidden ledger and a purchase at a market, ending with a woman refusing to live out a script written in male handwriting.

She did not name every name—not yet—but she named enough.

They hid copies around the house.

She entrusted one sealed envelope to Jonah.

“If something happens,” she said, “if you hear I’ve been taken ill suddenly, or sent away—this goes to the river.”

“You’re setting a fire,” Jonah said softly.

“You might not put it out.”

“I’m already in one,” she said.

“Now I’m deciding who burns.”

The reckoning wore its Sunday coat.

Augusta invited Marabel to a “gathering of concerned friends.” Late afternoon.

Augusta’s drawing room.

Trial.

Marabel dressed in the plainest black.

No hint of seduction.

She wanted them to see a widow with a ledger, not a woman with a lover in the carriage house.

As she buttoned gloves, Lazarus watched.

“You sure?” he asked.

“No,” she said.

“I’m going anyway.”

“If they hurt you,” he said, quiet steel, “I won’t sit chained and wait.”

“If they hurt me,” she said, “letters go out.”

Augusta’s drawing room was velvet and carved chairs, portraits of ancestors who had never lifted anything heavier than a spoon.

Tea and brandy—and acid fear beneath.

Silas was there.

The Whitfields.

Three other planters whose names appeared often in Victor’s book.

Their wives sat with composed faces and eyes that knew more than they would ever say.

“Mrs.

Ashford,” Augusta said, cordial and cool.

“Thank you for coming.”

“It seemed wise,” Marabel said, taking the empty chair set for her in the center.

“It is rarely good to ignore a summons from one’s betters.”

A ripple of discomfort.

Silas cleared his throat.

“We are here because of talk—disturbing talk.

Ledgers that should not exist.

Letters that might leave our city with false claims.

We thought it best to address matters within the family.”

“False,” she repeated, tasting the lie.

“Is that today’s choice?”

“Mrs.

Ashford,” the preacher said, hands folded.

“You are of good character.

We wish to believe you are misled—that grief and isolation have confused your judgment.”

“You mean you hope I’ve lost my mind,” she said.

“Mad women carry less weight.”

“Your behavior with that man you purchased is concerning,” Augusta said tightly.

“A widow receiving a male slave alone in her study at all hours.

The optics.

The danger to your reputation—and ours.”

Marabel looked slowly around the room, meeting eyes.

“My reputation concerns you now,” she said, “after you wrote my womb into your breeding plans.”

Gasps fluttered.

“Victor’s ledger,” she continued, voice low and carrying, “is full of your names.

It lists nights you invited men like Lazarus into your homes.

It explains why certain boys look as they do.

Do not call this madness.

Call it arithmetic.”

“Private matters,” a planter snapped.

“Family issues.

We did what was necessary to secure our lines.”

“By turning one man into a tool you passed around like a shared horse,” she said.

“By treating wives’ bodies as vessels for pride and fear.

Do not wrap it in necessity.”

Silas reddened.

“Enough,” he said sharply.

“This is precisely why such books should not be in women’s hands.

You lack context—”

“You mean profit,” she cut in.

“You mean interest.

You mean control.”

The preacher’s wife, pale but composed, spoke.

“Even if indiscretions occurred,” she said, “they were within marriage.

Within covenant.

You would tear apart families for what—vengeance?”

“I would tear apart a lie,” Marabel said.

“What follows is yours to choose.”

“Your position is precarious,” another man said.

“Debts.

No protector.

It would be simple to deem you unfit and place Ashford under trusteeship—for your own good.”

“And appoint whom?” she asked.

“Mr.

Gley? So you may tuck the ledger into fire and erase the record.” She reached into her reticule and pulled a folded paper.

“You underestimate me.

Copies exist.

Letters are written.

Burn this house—nothing changes that.”

Silas surged to his feet.

“You stupid girl,” he snarled, catching himself.

“You overstate your reach.

Northerners don’t care about nuance.

They’ll paint us monsters.”

“Then perhaps act less monstrously,” she said.

Silence fell heavy.

Augusta’s hand shook.

Her eyes found her eldest son—standing in the doorway, brow furrowed, listening.

She shut them.

“I will sign whatever papers you require for that man’s freedom,” she said, voice rough.

“I will speak to others.

Silas—you know as well as I—we’ve leaned on certain services.

We all carry stain.”

The preacher’s wife flinched.

She looked at her son—the jawline that matched a man by the river more than the man in the pulpit.

“Do it,” she whispered to her husband.

“Before the Lord does it for us.”

Reluctantly, grudgingly, the tide edged.

Not total victory.

Men bargained still—minimizing losses, drawing lines around what would be acknowledged.

But a path opened.

Documents were drafted.

Silas’s face carved stone as he drew new terms on the Ashford debts—interest lowered, timelines extended, certain liens quietly released.

A manumission paper for Lazarus bore three reluctant signatures.

“It ain’t freedom if they sign with pistols at backs,” Lazarus said when Jonah brought the paper to the carriage house.

“I’ll take it over iron.” He held the document like something fragile and unreal, reading his name in ink.

“So that’s it,” he said softly.

“A few strokes and I’m not property—on paper.”

“In their hearts,” Marabel said, “you’ll never be anything else.”

“And you?” he asked.

“I don’t know yet,” she said.

“But it’s not cattle.

And it’s not a stud in a ledger.”

He laughed—a real laugh.

It startled them both.

“What now?” he asked.

“You stay.

I go?”

“I can’t decide that for you,” she said.

“You’ve had enough choices taken.”

“You ever think of leaving?” he asked.

“Sell what you can.

Take coin.

Find a small place where no one knows Ashford.”

Late at night, she had.

She had imagined bread and dresses and quiet.

A life where her womb wasn’t a line item.

“I’ve thought about it,” she said.

“But I look at these fields and people—and know what kind of man would buy this place if I sell.

Someone who never saw the ledger—or pretended not to.

Someone who would turn it all back—or worse.

If I stay, maybe I bend things a little.”

“Then maybe I stay,” he said.

“For a while.

See if the bend holds.”

“People will talk,” she warned.

“They already do,” he said dryly.

“This time, maybe we write a line ourselves.”

Summer rolled in green.

Life did not become utopia.

Men shouted.

Whips cracked—less often under Jonah’s eye.

The world did not change overnight because of one ledger and signatures.

But some things shifted.

Marabel altered schedules.

Moved families closer.

Quietly banned sale of children under her authority.

When planters commented, she spoke their language—economics.

Healthy, stable workers worked better.

Lazarus took in-between roles—supervising repairs, overseeing shipments.

Some whites grumbled about an uppity freed man.

Some enslaved people eyed him uncertainly—ally or spy? He bore it.

Now, when he walked past fields, men didn’t look away as quickly.

Children straightened—seeing a possibility.

At night, sometimes they sat on the back porch in thick warmth—respectful distance between chairs.

They spoke of small things—weather, his childhood memories, her mother’s garden before debt swallowed it.

“Do you ever wish I hadn’t found that ledger?” she asked during a storm—lightning flickering far off.

He thought long.

“If you hadn’t,” he said slowly, “I’d be on some other man’s land doing what I was bought to do.

My back would ache.

I’d count days to ground.

You’d be in this house listening to Silas tell you what’s good.

You’d still be the virgin widow in their minds whether true or not.

Maybe you’d have a child chosen by them.

Maybe not.

Either way, you wouldn’t know why your life felt small.” He shrugged.

“I don’t know if what we got is better.

It hurts in different ways.

But at least when I look at a thing, I know what it is.

There’s power in that—even if it can’t save us from everything.”

Losses came.

A boy was beaten by a neighboring overseer during a cooperative harvest.

She argued and threatened—she could not undo damage.

An older woman died in childbirth—body worn by births demanded.

The ledger’s scars ran deeper than one woman’s will.

There were small gains.

A girl slated for sale was kept back—her price quietly paid from jewelry Silas had admired.

A family split years ago was partly reunited—Lazarus used fragile influence to redirect a purchase.

On Sundays, sermons grew oddly vague—less chastity, more mercy.

The preacher’s eldest son began standing in the yard with enslaved families instead of front pew.

No one dragged him forward.

Rumors continued.

People said the virgin widow was not so virgin—though they could not agree.

Some whispered she lay with a freed man under moonlight.

Others said she had taken a lover in New Orleans—a printer sending her radical books.

She did not bother to correct.

Let them spin stories they could swallow.

The truth did not fit their categories.

They were not lovers in the way people meant.

They shared no bed.

They did something more dangerous.

They shared knowledge—and acted.

One sticky night, a storm broke.

Rain hammered.

Thunder shook.

In the carriage house, a loose ceiling board gave way.

Water splattered the floor bolt where Lazarus’s chain had once fixed.

The iron ring—long unused—rusted and tore free.

It clanged to the floor.

Lazarus turned it in his hands in morning light.

“Guess time’s doing its own work,” he said.

Marabel set the broken ring on a shelf in Victor’s study beside the ledger.

A reminder: even strongest bolts rust.

No chain lasts forever.

There is more than one way for a system to rot.

She did not fool herself.

Outside her lines, the world remained cruel.

Men like Silas wrote contracts in ink that might as well be blood.

Children born of secrets walked paths others laid.

Somewhere in a printer’s shop far north, a story with her name had begun to circulate.

She knew it not because she had seen it yet but because letters began arriving—unknown hands writing to the widow who spoke.

Clumsy and eloquent notes proved her actions rippled beyond cane.

“What’s the worst that could still happen?” she asked Lazarus at dusk—cicadas screaming, fireflies blinking.

“They could change minds,” he said.

“Take back what they signed.

You could get sick and die before finishing.

War could come.

Or nothing could happen at all.

No big wave—just the slow same old swallowing what we did.”

“And the best?” she asked.

“Maybe some boy who never knew his father’s name reads about a man like him and realizes he’s not an accident to be ashamed of,” Lazarus said, sunset catching scar edges.

“Maybe some woman in a house like this looks at her husband’s locked desk and thinks, ‘What if I open it?’ Maybe we die and nothing much changes—but we die knowing we weren’t just ideas in other people’s heads.”

“That sounds like a kind of freedom,” she said.

“Maybe that’s all freedom is,” he replied.

“A say in your own story.”

Morning came.

Marabel walked through quiet rooms past portraits that looked less like authority and more like accusation.

In Victor’s study, the ledger and broken ring sat side by side.

She did not touch them.

She opened the window.

Cool air smelled of damp earth and possibility.

Outside, first light touched cane, gilding blades.

Near the north outbuilding, Lazarus’s low voice drifted—speaking to Jonah about the day’s work.

She stepped onto the porch.

Boards creaked under bare feet.

The world remained unjust.

In the small space she occupied, it had altered.

The widow who walked into the New Orleans market with veil and purse was not the same woman who stood now with ink stains and smoke of burned illusions in her lungs.

She was something new—unfinished and frightening to those who once wrote her into a ledger as if she were a horse.

She smiled a little at the thought.

Then Marabel Ashford went down the steps to meet the day—the echo of chains and scratch of pen strokes following her like ghosts and, maybe, like witnesses refusing to be quiet.

News

The most BEAUTIFUL woman in the slave quarters was forced to obey — that night, she SHOCKED EVERYONE

South Carolina, 1856. Harrowfield Plantation sat like a crowned wound on the land—3,000 acres of cotton and rice, a grand…

(1848, Virginia) The Stud Slave Chosen by the Master—But Desired by the Mistress

Here’s a structured account of an Augusta County case that exposes how slavery’s private arithmetic—catalogs, ledgers, “breeding programs”—turned human lives…

The Most Abused Slave Girl in Virginia: She Escaped and Cut Her Plantation Master Into 66 Pieces

On nights when the swamp held its breath and the dogs stopped barking, a whisper moved through Tidewater Virginia like…

Three Widows Bought One 18-Year-Old Slave Together… What They Made Him Do Killed Two of Them

Charleston in the summer of 1857 wore its wealth like armor—plaster-white mansions, Spanish moss in slow-motion, and a market where…

The rich farmer mocked the enslaved woman, but he trembled when he saw her brother, who was 2.10m

On the night of October 23, 1856, Halifax County, Virginia, learned what happens when a system built on fear forgets…

The master’s wife is shocked by the size of the new giant slave – no one imagines he is a hunter.

Katherine Marlo stood on the veranda of Oakridge Plantation fanning herself against the crushing August heat when she saw the…

End of content

No more pages to load