Dr.Patricia Morrison had spent 15 years studying historical medical photographs, but the image she unwrapped that October morning would haunt her for the rest of her career.

The photograph had arrived as part of a donated collection from a Philadelphia family estate.

Boxes of documents, letters, and images documenting the city’s industrial history.

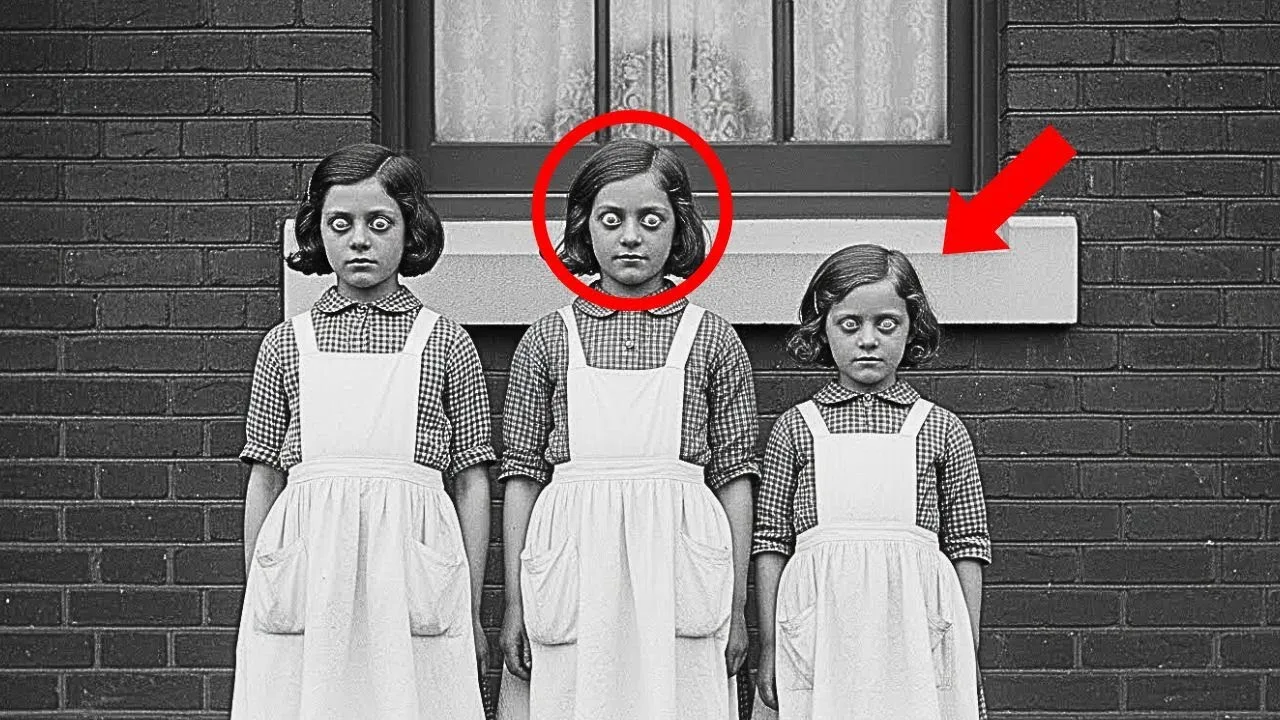

The photograph showed three young girls standing in a row wearing identical simple cotton dresses and work aprons.

Their ages appeared to range from about 8 to 13 years old.

They stood in front of a brick building and a handwritten caption on the back read, “Heartley Sisters, Riverside Textile Mill, Philadelphia, June 1913.” Patricia positioned the photograph under her examination lamp at the Medical History Museum where she worked as chief curator.

The image quality was remarkably good for its age.

The photographer had captured fine details with impressive clarity.

She could see the texture of the brick wall behind the girls, the pattern of their dresses, even individual strands of hair.

The girls expressions were what first caught her attention.

They weren’t quite smiling, but their faces showed a kind of forced cheerfulness.

The look of children told to appear happy for the camera.

Their posture was stiff, formal, uncomfortable, but it was their eyes that made Patricia pause and lean closer.

Something about the girl’s eyes seemed wrong.

She adjusted her magnifying lamp and studied each face carefully.

The pupils, all three girls had pupils that appeared unusually large, dilated far beyond what the lighting conditions would explain.

Patricia had examined thousands of historical photographs.

She understood how light, exposure times, and photographic chemistry affected images.

But these pupils were distinctly abnormal.

In the bright outdoor light visible in the photograph, pupils should have been contracted small.

Instead, all three girls showed extreme pupil dilation, midriasis in medical terms.

She photographed the image with her highresolution camera and uploaded it to her computer, zooming in on each girl’s face.

The digital magnification confirmed what she’d seen.

The pupils were enormous, nearly obscuring the irises entirely.

This wasn’t a photographic artifact or a trick of the light.

This was a medical condition captured on film.

Patricia felt a chill run down her spine.

She had seen pupil dilation like this before in historical photographs of patients who had been given certain drugs.

Atropene, Belladana, opiates.

The dilation was a clear pharmacological response, not a natural state.

Three young girls working in a textile mill in 1913, all showing identical signs of drug exposure.

Patricia knew she had stumbled onto something significant and deeply troubling.

She needed to understand what had happened to the Hartley sisters and why their eyes told a story their forced smiles tried to hide.

Patricia began her investigation with the most basic question.

Who were the Hartley sisters and what was Riverside Textile Mill? Philadelphia City directories from 1913 showed Riverside Textile as a medium-sized fabric manufacturer operating in the Kensington neighborhood, an area known for its concentration of textile factories and mills.

The mill had employed approximately 200 workers, producing cotton fabrics for clothing manufacturers.

Records showed it operated from 1898 until 1925 when it was shut down following multiple safety violations and labor disputes.

But those basic facts told Patricia nothing about the three girls in the photograph or why their pupils had been so dramatically dilated.

She contacted the Pennsylvania State Archives requesting access to any surviving records from Riverside Textile.

3 days later, she received a response.

The archives held employment records, payroll documents, and some correspondence from the mills operations between 1910 and 1915.

Patricia traveled to Harrisburg to examine the materials.

The employment ledgers were revealing and disturbing.

The mill had employed numerous children, some as young as 7 years old, despite Pennsylvania’s supposed restrictions on child labor.

The Hartley sisters appeared in the 1913 payroll.

Rose Hartley, age 13, wage 320 per week.

Margaret Hartley, age 10, wage 240 per week.

Katherine Hartley, age 8, wage 180 per week.

The wages were shockingly low.

Adult workers at the mill earned between $8 and $12 per week.

Children were paid a fraction of adult wages for doing similar work, often for even longer hours since they were considered more compliant and less likely to complain about conditions.

Patricia found a document that made her investigation suddenly more urgent.

A notice from the Pennsylvania Department of Factory Inspection dated July 1913, just 1 month after the photograph had been taken.

The notice documented a surprise inspection of Riverside Textile and listed numerous violations, including employment of children under age 10, excessive working hours exceeding state limits, and one notation that caught Patricia’s attention, evidence of patent medicines being administered to child workers.

The inspector’s report elaborated, observed supervisor distributing liquid tonic to child workers during shift.

When questioned, supervisor claimed this was voluntary health supplement provided by mill management to boost workers energy and health.

Several children showed signs of excessive stimulation, rapid speech, enlarged pupils, apparent inability to remain still.

Recommend investigation of substances being administered.

Patricia’s hands trembled as she read.

The dilated pupils in the photograph weren’t a mystery.

They were evidence of systematic drugging.

The mill had been giving children substances that caused pharmacological effects, and the state inspector had noticed and documented it.

But what had happened after that inspection? Had anyone been held accountable? Had the practice been stopped? She continued searching through the archives and found correspondence between the factory inspector and the mills owner, a man named Howard Brennan.

Brennan’s response to the inspection was dismissive and defensive.

The health tonics provided to our workers are standard commercial preparations, widely available and perfectly safe.

They contain beneficial ingredients that improve stamina and concentration, allowing our employees to work more efficiently.

There is nothing improper or dangerous about this practice.

Patricia needed to understand what was in those health tonics and what effects they had on the children who were forced to consume them.

To understand what the H Heartley sisters had been given, Patricia needed to research the patent medicine industry of the early 1900s.

She contacted Dr.

Robert Chen, a colleague who specialized in pharmaceutical history and had written extensively about the unregulated drug market of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Dr.

Chen was immediately interested in Patricia’s findings.

The early 1900s were the peak of the patent medicine era, he explained when they met.

Companies sold thousands of different tonics, elixirs, and remedies with virtually no regulation.

Many contained dangerous substances, cocaine, morphine, heroin, alcohol, even mercury, and arsenic.

They were marketed as curalls for everything from fatigue to tuberculosis.

He pulled up advertisements from 1913 showing various workers tonics and energy elixir marketed specifically to factories and employers.

The ads promised to increase productivity, eliminate worker fatigue, and maintain alertness during long shifts.

Many featured testimonials from factory owners praising the increased output they achieved after implementing regular tonic distribution.

The most common active ingredient in these worker tonics was ldinum, tincture of opium.

Doctor Chen explained, “Oop derivatives produce a sense of euphoria and energy initially before the sedative effects set in.

They also cause dramatic pupil dilation, which is exactly what you’re seeing in your photograph.” Other common ingredients included cocaine, which was perfectly legal and considered a miracle drug for energy and focus, and various forms of alcohol.

Patricia felt sick.

The H Heartley sisters, children as young as 8 years old, had been given opium based drugs to make them work longer and harder.

The health tonics had nothing to do with health and everything to do with exploitation.

Dr.

Chen showed her a medical journal article from 1912 warning about the dangers of administering stimulants to child workers.

The article described cases of children developing dependence, suffering from malnutrition exacerbated by appetite suppression.

and experiencing long-term developmental problems.

But the article had little impact.

Patent medicines remained unregulated until the Harrison Narcotics Act of 1914.

And even then, enforcement was weak for several years.

What would have happened to children who were given these substances regularly? Patricia asked.

Dr.

Chen’s expression was grim.

Dependence would develop quickly, especially in children.

Their bodies would adapt to the presence of opiates requiring increasing doses to achieve the same effect.

When access was cut off, if they left the job, or if the employer stopped providing the drugs, they would experience withdrawal.

For children, that could be devastating.

Severe pain, vomiting, seizures.

Many wouldn’t survive withdrawal without medical care, and most wouldn’t have had access to such care.

Patricia thought of the three girls in the photograph.

Their pupils dilated by drugs they had no choice but to consume.

What had happened to them after that photo was taken? Had they survived? Had they escaped? Or had they become trapped in a cycle of dependence and exploitation? Patricia returned to Philadelphia determined to trace what had happened to Rose, Margaret, and Catherine Hartley after 1913.

She began with census records.

The 1910 census showed the three girls living with their widowed mother, Ellen Hartley, in a cramped tenement in Kensington.

Ellen was listed as a laress, earning barely enough to feed her daughters.

All three girls were listed as at home too young yet to work, though that would soon change.

By the 1920 census, Patricia could find no trace of the Hartley family at their previous address or anywhere in Philadelphia under that name.

They had either moved, married, and changed names or died.

Given the circumstances, Patricia feared the worst.

She expanded her search to death records, and what she found was heartbreaking.

Margaret Hartley, the middle sister, appeared in Philadelphia death records from November 1914.

She had died at age 11.

The cause of death was listed as acute gastric distress and convulsions.

Patricia recognized these symptoms as consistent with drug withdrawal or poisoning.

Catherine Hartley, the youngest, appeared in death records from March 1915.

She had been 9 years old.

The cause of death was listed as respiratory failure, another symptom that could indicate opiate related complications.

Two of the three sisters had died within 2 years of the photograph being taken, both at ages when children should have been playing and learning, not working 14-hour days in factories while being given dangerous drugs.

But Rose, the eldest, did not appear in death records from that period.

Patricia searched through marriage records and found her.

Rose Hartley had married in 1918 at age 18, becoming Rose Collins.

The marriage record listed her occupation as none, and included a notation that she was of limited capacity, a term used at the time to indicate intellectual or physical disability.

Patricia traced Rose through subsequent census records.

In 1920, she was living in an institution called the Philadelphia Home for Incurables.

The census listed her as permanently disabled and noted she was unable to care for herself.

She remained institutionalized for the rest of her life.

Patricia found Rose’s death certificate from 1967.

She had lived to age 67, spending nearly 50 years in institutional care.

The death certificate listed the cause of death as pneumonia, but noted long-term effects of childhood drug exposure as a contributing factor.

Someone decades after the fact had recognized what had been done to her and documented it.

Patricia sat in the archives surrounded by the documentation of three young lives destroyed.

The photograph had captured them at what might have been their last moment of relative health before the drugs they were being given completed their destruction.

Two had died as children.

One had survived but been so damaged that she spent her entire adult life institutionalized.

The cheerful expressions they had been told to wear for the camera now seemed like a cruel mockery.

A lie captured on film while their eyes had told the truth that their voices couldn’t speak.

Patricia’s next discovery came from an unexpected source.

A librarian at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania contacted her after hearing about her research.

The library had a small collection of letters from the early 1900s written by workingclass women.

Donations from various families that had been minimally cataloged and rarely examined.

Among them were letters written by Ellen Hartley, the mother of the three girls.

The letters were addressed to her sister in Boston and documented Ellen’s increasingly desperate attempts to protect her daughters while keeping them employed so the family could survive.

A letter from May 1913, one month before the photograph was taken, read, “Dear Mary, the girls are all working at the mill now.

Even little Catherine, though she’s only eight and so small for her age.

I hate sending her there, but we need every penny.

Rose brings home 320 each week, Margaret 240, and Catherine 180.

Together with my laundry work, we can almost pay our rent and buy food.

Almost, the letter continued.

But Mary, I’m worried sick about them.

They come home exhausted, their fingers bleeding from the machines, their eyes strange and glassy.

The foreman gives them some kind of medicine during their shifts.

He says it helps them work better and stay alert.

The girls say it makes them feel strange, like they’re floating and they can’t sleep properly at night.

Rose has nightmares and Catherine sometimes doesn’t recognize me for a few moments when she first comes home.

What are they giving my daughters? A letter from July 1913 showed Ellen’s growing alarm.

The factory inspector came last month and there was talk of the medicines being stopped.

But the foreman says if the girls won’t take the medicine, they’ll be dismissed.

And if they’re dismissed, we’ll starve.

I don’t know what to do, Mary.

I watch my daughters changing, becoming thin and nervous, and I feel like I’m watching them die slowly.

But if I take them out of the mill, we’ll have no money for food or rent.

What kind of choice is that for a mother? The letters from late 1914 documented Margaret’s final illness.

Margaret has been sick for weeks.

She vomits constantly and her body shakes.

The doctor says it’s her stomach, but I know it’s from those medicines they gave her at the mill.

She hasn’t been back to work in a month.

She’s too weak.

Without her wages, we’re falling behind on rent.

Rose and Catherine are working extra hours to make up the difference, which means they’re taking more of those terrible medicines.

I’m watching one daughter die while the others are being poisoned further.

God forgive me.

I don’t know how to save them.

Margaret died in November 1914.

Ellen’s letter to her sister after Margaret’s death was brief and devastating.

My Maggie is gone.

The doctor said her insides just gave out.

Her stomach, her heart, everything failing at once.

She was 11 years old.

11.

And I sent her to that mill.

I let them poison her because we needed the money.

I’m her mother and I couldn’t protect her.

The final letters documented Catherine’s decline and death.

Then Rose’s increasing disability.

By 1916, Ellen was writing.

Rose can no longer work.

Her mind is gone.

She doesn’t remember things.

She can’t follow simple instructions.

She has seizures several times a week.

The doctor says her brain has been permanently damaged by the drug she was given.

I’ve applied to have her admitted to an institution because I can’t care for her properly while also working enough to support us both.

What have I done to my children, Mary? What have I done? Patricia found Ellen Hartley’s death certificate from 1922.

She had died at age 49 of a heart attack.

Though Patricia suspected grief and guilt had contributed as much as any physical cause, she had outlived two of her daughters and watched the third become permanently disabled.

All because poverty had forced her to send her children to work in a mill that drugged them to increase productivity.

Patricia needed to understand how the mill’s management had justified drugging child workers.

She returned to the archives and found correspondence and legal documents from 1914 and 1915.

When the Pennsylvania authorities had finally taken action against Riverside Textile Mill following multiple worker deaths and the inspector’s reports about drug administration, Howard Brennan, the mill owner, had hired lawyers to defend the practice.

Patricia found copies of legal briefs arguing that the health tonics were beneficial to workers, that they were commercially available products, and that the mill had actually been doing the workers a favor by providing them at no cost.

One brief argued, “These tonics are purchased from reputable pharmaceutical suppliers and contain ingredients that have been used for centuries to promote health and vigor.

Coffee, which contains stimulating properties, is consumed daily by millions without objection.

The tonics provided by Riverside Textile Mill contain similar beneficial ingredients that allow workers to perform their duties more effectively and with less fatigue.

There is no difference in principle between providing workers with coffee and providing them with health tonics.

The argument was deliberately misleading, comparing opiate-based drugs to coffee, but without clear regulations defining what substances were acceptable.

The mills lawyers had successfully muddied the legal waters.

Patricia found testimony from Brennan himself during a 1915 hearing.

I have always maintained safe and healthful working conditions.

The tonics we provided were recommended by our company physician and were intended to protect workers health during long shifts.

If some workers experienced adverse reactions, that is unfortunate, but it does not indicate any wrongdoing on our part.

We were operating within the norms of industrial practice at the time.

What infuriated Patricia most was Brennan’s claim of ignorance about the tonic’s contents.

Records showed he had personally negotiated with suppliers, purchasing large quantities of patent medicines at bulk prices.

He had known exactly what he was buying and why, not to protect workers’ health, but to extract more labor from exhausted bodies, including those of children.

The legal case against the mill had eventually been settled quietly.

Brennan paid a modest fine, agreed to discontinue the tonic distribution, and faced no criminal charges.

By 1915, the legal scrutiny had made the practice too risky, but the damage had already been done to hundreds of workers, including the Hartley Sisters.

Patricia found Brennan’s obituary from 1932.

He had died wealthy and respected, his obituary praising his contributions to Philadelphia’s industrial development, and making no mention of the workers who had been harmed under his supervision.

He had lived comfortably into old age while Rose Hartley spent her life institutionalized and her sisters died as children.

The injustice of it burned in Patricia’s chest.

Brennan had faced minimal consequences while the families he had exploited carried the costs for generations.

Patricia wanted to understand more about the photograph itself, who had taken it and under what circumstances.

The photographers’s mark on the back of the image was partially legible.

Kin Studio Filela.

Research through city directories helped her identify it as Watkins Photography Studio operated by a photographer named Samuel Watkins who specialized in industrial and commercial photography.

She found Watkins business records at the Philadelphia Historical Commission.

Among them was a ledger showing the commission for the Hartley photograph.

June 1913 Riverside Textile Mill promotional photographs of workers 15 nondellers.

The entry included a brief note requested cheerful images of child workers for Mills public relations materials.

But more interesting was a personal journal that Watkins had kept documenting his photography work and his reflections on the subjects he photographed.

Patricia found an entry from June 1913 that clearly referred to the Hartley sisters.

Photographed three young sisters at Riverside Mill today.

The management wanted images showing healthy, happy child workers to counter recent negative publicity about their employment practices.

But these girls looked anything but healthy.

They were painfully thin.

Their skin had an unhealthy palar.

And most disturbing were their eyes, pupils massively dilated, giving them an almost frightening appearance.

I’ve photographed many mill workers, and I know what exhaustion looks like.

This was something different, something pharmaceutical.

When I asked the foreman about the girl’s appearance, he claimed they were simply excited to have their photograph taken.

But I’ve been photographing people for 20 years, and I know the difference between excitement and drug effects.

I positioned the girls to capture their faces clearly, including their eyes.

Perhaps someday someone will look at this photograph and understand what I understood, that these children were being harmed in ways that went beyond long hours and dangerous machines.

Patricia felt a connection across more than a century to Samuel Watkins.

He had seen what was being done to the H Heartley sisters and had deliberately documented it, preserving evidence even when he couldn’t act on it directly.

His photograph had indeed fulfilled his hope.

Someone had finally looked closely and understood.

She found more journal entries documenting Watkins growing discomfort with industrial photography assignments.

In 1914, he wrote, “I’ve decided to stop accepting commissions from factories and mills.

I can no longer participate in creating propaganda that helps these places hide the truth about how they treat their workers.

My photographs should document reality, not help disguise it.” Watkins had died in 1928, and his obituary mentioned that he had spent his later career documenting social conditions and labor issues, providing photographs to reform organizations without charge.

He had apparently tried to atone for his earlier complicity in industrial propaganda by using his skills to expose rather than conceal the truth.

Patricia realized that the Hartley sister’s story was not unique.

It was representative of a widespread practice that had affected thousands of child workers across American industry.

She began researching other cases of drug administration to workers, particularly children, in early 20th century factories.

What she discovered was shocking in its scope.

Dozens of factories had provided health tonics, energy elixirs, or fatigue remedies to workers, particularly during busy seasons when long hours were required.

The practice was especially common in textile mills where children made up a significant portion of the workforce and where their small size and supposed dexterity made them valuable for certain tasks.

Medical journals from the 1910s and 1920s documented the consequences.

Articles described epidemics of drug dependence among former child workers, cases of permanent neurological damage, and premature deaths attributed to long-term exposure to opiate-based medicines.

One 1918 medical study estimated that tens of thousands of American workers, including thousands of children, had been affected by workplace drug administration between 1900 and 1915.

Patricia found court cases similar to the one involving Riverside Textile.

Factories sued by families of workers who had died or been disabled.

Most cases were settled quietly with companies paying modest damages while admitting no wrongdoing.

A few resulted in small fines.

None resulted in criminal prosecutions of owners or managers.

The practice had finally been largely eliminated by the early 1920s.

Not because of legal enforcement, but because negative publicity made it too risky and because the Harrison Narcotics Act of 1914 had gradually made it more difficult to obtain bulk quantities of opiate-based medicines without scrutiny.

But for the children who had been exposed during the peak years between 1900 and 1915, the reforms came too late.

Patricia estimated that thousands had died prematurely.

Thousands more had lived with disabilities and dependent and countless families had been destroyed by the consequences.

She compiled her research into a comprehensive report documenting the systematic drugging of child workers using the Hartley sister’s photograph as a central piece of evidence.

The dilated pupils that had first caught her attention became a symbol of a hidden epidemic that had affected an entire generation of working-class children.

Patricia organized an exhibition at the Medical History Museum titled Hidden Harm: The Drugging of America’s Child Workers.

The centerpiece was the photograph of the Hartley Sisters, displayed alongside medical explanations of what the dilated pupils indicated and detailed documentation of what had happened to the girls after the photo was taken.

The exhibition included Ellen Hartley’s letters, Samuel Watkins journal entries, medical records, legal documents, and comparative photographs showing other child workers with similar signs of drug exposure.

Patricia also included information about the patent medicine industry, samples of actual workers tonics from the era with their shocking ingredient lists, and testimony from doctors who had treated the resulting casualties.

But she also wanted to make the human cost clear.

She created biographical panels for Rose, Margaret, and Catherine Hartley, showing their short lives and tragic fates.

Visitors could read about Margaret’s death at 11, Catherine’s death at 9, and Rose’s 50 years of institutionalization.

The contrast between their cheerful, forced expressions in the photograph, and the documentation of their suffering was deliberately stark and deeply affecting.

The exhibition opened to significant media attention.

Local and national news outlets covered the story, shocked by the revelation that thousands of American children had been systematically drugged by their employers.

The photograph of the Hartley sisters with their tellingly dilated pupils was reproduced widely and became iconic.

Child welfare advocates and historians praised the exhibition for exposing a forgotten chapter of labor history.

Several organizations working on contemporary child labor issues internationally drew parallels between the practices Patricia documented and current exploitation of children in manufacturing worldwide.

But the most moving responses came from visitors, particularly from elderly people who remembered family members who had worked in similar conditions.

The museum’s comment book filled with stories.

My grandmother worked in a mill as a child and was given medicine that she said made her feel strange.

She died at 32, never healthy.

Now I understand what was done to her.

Another wrote, “I’m a recovering addict, and learning that children were deliberately given opiates by their employers makes me think differently about addiction.

These weren’t people making poor choices.

They were victims of exploitation.” How many addicts today are descendants of workers who were forcibly exposed to these drugs? One particularly moving comment came from a woman who identified herself as a distant relative of the Hartley family.

I never knew the full story of what happened to Rose, Margaret, and Catherine.

Our family only knew they had worked in Mills and that something terrible had happened.

Thank you for giving them back their story and for making sure people understand what was done to them.

They deserved better then and they deserve to be remembered now.

The exhibition ran for a year at the Medical History Museum and then traveled to other cities, bringing the Hartley Sister story to audiences nationwide.

Everywhere it went, it sparked conversations about child labor, corporate responsibility, drug policy, and the long-term consequences of exploitation.

Patricia was invited to speak at conferences and universities about her research.

She emphasized that while the specific practice of drugging child workers had been eliminated, the underlying dynamic, corporations prioritizing profit over worker well-being, particularly the well-being of the most vulnerable, remained relevant.

When I look at the Hartley sisters photograph, she told one audience, “I see three children whose bodies were treated as machines to be chemically manipulated for maximum productivity.

They were given drugs not to help them but to extract more labor from them.

And when those drugs destroyed their health, they were discarded.

That fundamental disregard for human well-being in pursuit of profit didn’t end in 1915.

It takes different forms today, but the ethical failures are the same.

The research influenced contemporary discussions about workplace drug testing, workplace wellness programs, and the ethics of employer involvement in workers health decisions.

Some scholars drew connections between the historical drugging of workers and contemporary controversies about companies monitoring employees health or requiring participation in wellness programs.

Labor historians incorporated Patricia’s findings into textbooks and courses, ensuring that future generations would learn about this chapter of exploitation.

The photograph of the Hartley sisters, with their dilated pupils clearly visible, became a standard image in discussions of child labor history and the unregulated patent medicine era.

Patricia arranged for a memorial marker to be placed in Kensington, in the neighborhood where Riverside Textile Mill once stood.

The marker included a replica of the photograph and text explaining, “In memory of Rose, Margaret, and Catherine Hartley, and the thousands of other children who worked in Philadelphia’s mills and factories in the early 1900s, many were given dangerous drugs by their employers to increase productivity, resulting in dependence, disability, and premature death.

Their suffering led to reforms in child labor laws and drug regulation that continue to protect workers today.” At the marker’s dedication ceremony, Patricia spoke about the importance of looking closely at historical evidence and being willing to see what’s uncomfortable.

For more than a century, people looked at this photograph and saw three smiling girls.

It took medical knowledge and careful observation to see the dilated pupils and understand what they meant.

Sometimes the truth is hidden in plain sight, waiting for someone with the knowledge and the courage to recognize it.

Rose, Margaret, and Catherine couldn’t speak openly about what was being done to them, but their eyes told the truth.

By paying attention to that truth, by investigating and documenting it, we honor their memory, and we protect future generations from similar exploitation.

The photograph remained in the museum’s permanent collection.

Roses, Margaret’s and Catherine’s faces forever young, their eyes forever dilated, their forced smiles forever contradicted by the medical evidence of what they had endured.

But now, finally, their story was known and remembered, a testament to both the cruelty of unchecked industrial capitalism, and the importance of examining closely what history tries to hide.

Patricia had given the Heartley sisters something they never had in life.

A voice, an acknowledgement of what had been done to them, and the assurance that their suffering had not been forgotten or dismissed as merely an unfortunate but unavoidable cost of progress.

Their tragedy had become a catalyst for understanding and a reminder that behind every historical photograph are real people whose experiences deserve to be seen, understood, and remembered truthfully.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load