The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected.

The March wind rattled the windows of the Boston Historical Society as Daniel Parker carefully removed the photograph from its protective sleeve.

At 41, he had curated hundreds of historical images.

But something about this particular portrait made him pause before even examining it closely.

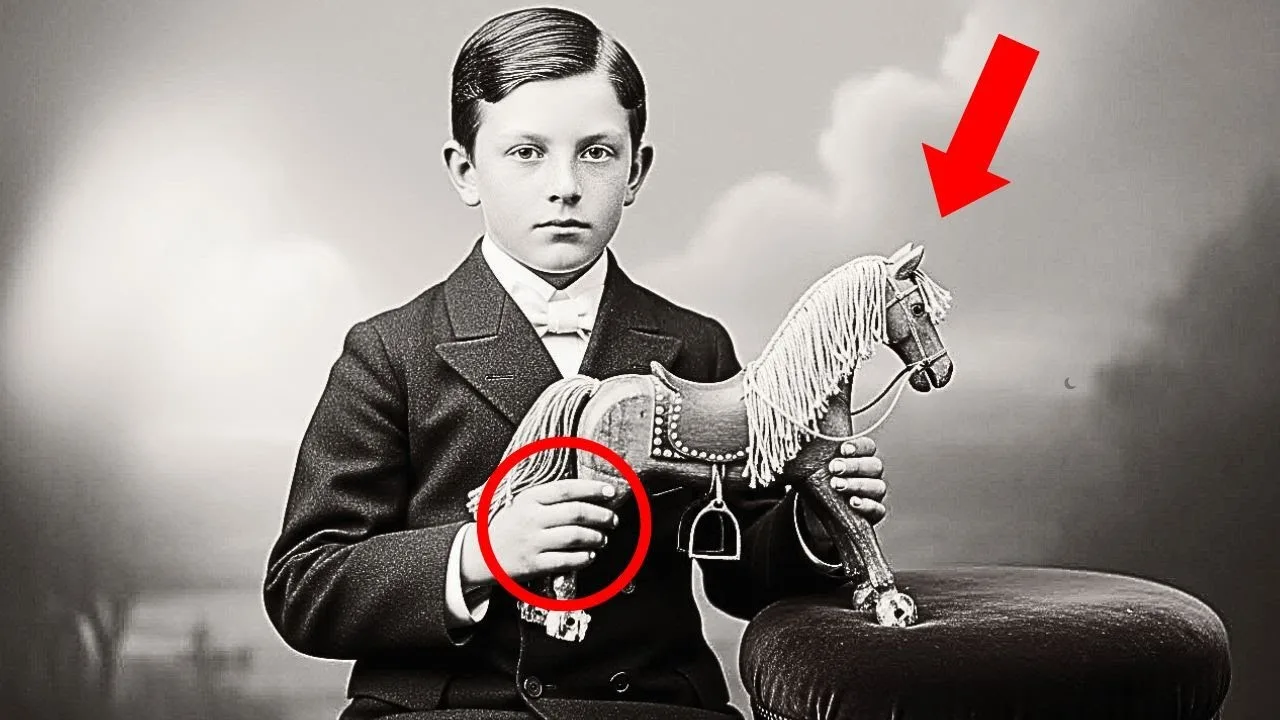

The photograph showed a boy of perhaps 8 or 9 years old, seated in a simple wooden chair against a plain backdrop.

He wore a threadbear jacket that had been carefully cleaned for the occasion.

His collar starched despite its frayed edges.

In his small hands, he held a wooden toy horse exquisitly carved with remarkable detail, flowing mane, muscular hunches, tiny hooves that showed the craftsman’s skill.

But it was the boy’s face that arrested Daniel’s attention.

Unlike most children photographed in that era, who showed either forced semnity or barely suppressed fidgeting, this child’s expression was haunting [music] in its emptiness.

His eyes stared directly at the camera with a flatness that suggested he was looking at nothing at all.

Dark circles shadowed those eyes, and his skin had a palar that seemed unnatural, even accounting for the photographic processes of 1904.

Daniel adjusted his magnifying lamp, leaning closer.

The studio mark on the reverse indicated Thompson Photography, a small establishment that had operated in Boston’s North End between 1902 and 1908.

The handwritten notation read, [music] “Master Thomas, March 1904, Special Commission, payment [music] received.” He began his standard documentation process.

Photographing the image at high resolution.

As the digital file loaded on his computer screen, he zoomed in on details invisible to the naked eye.

The boy’s hands drew his attention.

They weren’t merely dirty from a child’s play.

Dark staining marked his palms and fingertips.

Discoloration that seemed to have soaked into the skin itself.

Daniel zoomed in on the toy horse.

What had appeared to be shadows cast by the studio lighting revealed themselves as something else.

dark streaks and spots marring the painted surface, as if the paint itself had been applied unevenly or had begun to deteriorate even before the photograph was taken.

He leaned back, a familiar unease settling in his chest.

20 years of historical research had taught him to recognize when a photograph held more than its surface showed.

This image, donated anonymously to the society’s collection the previous week, was hiding something.

The question was what and why someone had wanted it preserved.

By morning, Daniel had printed the highresolution image at poster size and pinned it to his office wall.

He stood before it with his coffee, studying details that emerged with scale and clarity.

The photograph was professionally composed, suggesting the family had paid for a formal sitting, not an insignificant expense for people whose clothing suggested modest means at best.

He called his colleague Dr.

Sarah Chen, a medical historian at Boston University who specialized in occupational diseases of the industrial era.

She arrived at noon.

Her interest peaked by Daniel’s cryptic email about possible toxicological evidence in a historical photograph.

Sarah stood before the enlarged image, her trained eye moving systematically across the boy’s features.

“Tell me what you see,” she said, [music] a teaching habit from her years in academia.

A sick child, Daniel replied.

The palar, the dark circles under his eyes, the way he’s holding himself very still, like movement costs too much [music] effort.

Good.

What else? Daniel pointed to the boy’s hands.

This discoloration.

[music] At first, I thought it was just dirt, but it’s too uniform, [music] too deeply set into the skin, and it’s primarily on his palms and the pads of his fingers.

Sarah pulled out her own magnifying glass, examining the hands closely.

This isn’t dirt.

[music] This is staining from prolonged contact with something, likely a chemical compound.

See how it’s concentrated on the areas that would grip or handle objects? She moved her attention to the toy horse, and this toy shows similar discoloration, dark spots, streaking.

If I had to guess, I’d say this is heavy metal contamination, lead, possibly arsenic.

From what source? That’s the question.

Sarah photographed the image with her phone, zooming in on various details.

In 1904, lead and arsenic compounds were common in industrial processes, paint manufacturing, textile dyes, ceramic glazes.

But to see this level of contamination on a child, she paused her expression darkening.

Tell me the photograph’s provenence.

Donated anonymously last week.

No accompanying documentation, just a note saying it was found in an estate sale in the North End.

The studio mark indicates Thompson Photography, which operated from 1902 to 1908.

Sarah turned to him.

[clears throat] The North End in 1904 was densely packed with tenement housing and small factories.

There were dozens of manufacturing operations crammed into converted residential buildings, including toy factories.

The pieces began clicking together in Daniel’s mind.

You think this boy worked in a factory? I think this boy was dying from factory work, Sarah said quietly.

And someone paid to have his portrait taken.

The question is why? Daniel spent the next two days in the city archives pulling records from the north end during the first decade of the 20th century.

The neighborhood had been a warren of immigrant families, mostly Italian and Irish, packed into tenementss where entire families often shared single rooms.

Ground floors and basement of these buildings frequently housed small manufacturing operations, [music] garment sweat shops, cigar factories, and toy workshops.

The fire marshall’s records from 1904 listed 17 toy manufacturing operations in the North End alone.

Most were small enterprises employing between 5 and 20 workers, many of them children.

The inspections were prefuncter at best.

Brief notations about adequate ventilation and no immediate fire hazards that suggested the inspectors had spent mere minutes in each location.

One entry caught Daniel’s attention.

Bellingham toy company, [music] 47 Handover Street.

Ground floor workshop produces wooden toys and painted soldiers.

Employs eight workers.

Note strong chemical odor throughout premises.

Advised improved ventilation.

He cross- referenced the address with city directories.

The building at 47 Hanover Street had been demolished in 1952, [music] replaced by a parking garage.

But the 1905 directory listed the building’s occupants, Bellingham Toy Company, on the ground floor with three residential apartments above housing the families of Italian immigrants.

Daniel found the business license for Bellingham Toy Company, issued in 1899 to one Edward Bellingham, age 42, [music] occupation listed as toy maker.

The license renewal in 1904 was the last on record.

The company disappeared from city documents after 1906.

The Boston Globe Archives offered fragments of the larger story.

A brief article from April 1904, buried on page 7.

Child labor reform advocates call for stricter regulations.

Local factories employ children as young as six in hazardous conditions.

Toy workshop cited for use of dangerous paint compounds.

Another article from October 1904.

Three children hospitalized with lead poisoning.

Physicians trace exposure to toy factory employment.

Parents demand accountability.

Daniel printed the articles and added them to his growing file.

[music] The pieces were connecting, but he needed more.

He needed to identify the boy in the photograph to understand who he was and why his portrait had been taken.

That evening, he returned to the photograph, studying the boy’s face with new understanding.

[music] This wasn’t just a formal portrait.

This was documentation of something, [music] evidence perhaps, or a memorial.

The boy’s empty expression, the careful positioning of the toy horse in his hands, the note on the reverse about special commission, all suggested intentionality beyond a simple family photograph.

He thought about the parents who would have brought their dying child to a photography studio.

Who would have paid money they likely couldn’t spare for this image? What had they hoped to preserve? What had they needed to remember or prove? Sarah returned to Daniel’s office 3 days later with a colleague, Dr.

Dr.

James Morrison, a chemist who specialized in historical industrial compounds.

James examined the enlarged photograph with scientific precision, taking measurements and making notes in a leather-bound journal.

The discoloration pattern is consistent with chronic exposure to lead-based compounds.

James said after 30 minutes of study, see how it’s concentrated on the fingertips and palms.

That suggests repeated handling of freshly painted objects.

[music] The staining penetrates the skin because lead acetate and lead carbonate, common in paints of this era, can be absorbed through the epidermis with prolonged contact.

“What about the toy itself?” Daniel asked.

“The dark streaks and spots suggest the paint was mixed with excessive lead content, possibly to achieve brighter colors or faster drying times.

Manufacturers often added lead compounds without understanding or caring about the toxicity.” James pointed to specific areas of the wooden horse.

Look here [music] at the main and tail.

The paint appears almost crystalline in structure, which happens when lead content exceeds 50% of the paint composition.

Sarah pulled up research on her laptop.

I’ve been reviewing medical literature from the period.

Lead poisoning in children presents with specific symptoms.

PAR, fatigue, abdominal pain, cognitive impairment, and in severe cases, seizures and coma.

The mortality rate for children with acute lead poisoning in 1904 was approximately 30%.

And for chronic low-level exposure, Daniel asked, worse in some ways.

The poisoning happens slowly, accumulating over months or years.

Symptoms develop gradually.

The child becomes increasingly lethargic, loses appetite, develops headaches.

By the time the condition is recognized, significant neurological damage has often occurred.

James returned to his examination of the photograph.

The boy’s posture is telling.

He’s sitting very still, but notice the tension in his shoulders, the way his jaw is clenched.

That suggests chronic pain, common with lead poisoning due to abdominal cramping and bone pain.

Daniel felt a wave of sadness wash over him.

“How old would you estimate he is?” “8, maybe 9 years old,” Sarah said.

But malnutrition and chronic illness could make him appear younger than his actual age.

Child laborers of this era were often stunted in growth due to poor nutrition and the physical demands of factory work.

They stood [music] in silence before the photograph.

Three scholars bearing witness to a century old tragedy preserved in sepia tones.

The boy stared back at them with those empty eyes holding the toy that had slowly killed him.

We need to find out who he was, Daniel said.

Finally.

Someone took this photograph for a reason.

Someone wanted him remembered.

Daniel requested access to the Boston City Hospital records from 1904.

Explaining his research to the hospital’s archivist.

After [music] two weeks of paperwork and approvals, he received permission to examine non-patient specific documents, admission logs, statistical reports, and public health records that didn’t contain identifying medical information.

The public health department’s annual report for 1904 contained a section titled industrial diseases in children.

Daniel’s hands trembled slightly as he read, “This year saw a marked increase in cases of plumism, lead poisoning among children employed in manufacturing.

23 cases were admitted to city hospital [music] with eight fatalities.

The majority of affected children worked in toy factories, paint shops, and ceramic studios.

Despite calls for regulation, enforcement remains minimal.

A supplementary document listed the factories associated with poisoning cases, though no names were given for the children.

Bellingham Toy Company appeared three times.

Daniel photographed the pages with his phone, his anger building as he read descriptions of children as young as 6 years old, working 12-hour days painting toys with lead-based compounds, their small hands ideal for detail work.

He cross-referenced death certificates from 1904, searching for children aged 810 from the North End who died between March and December.

The records were handwritten, often barely legible.

Causes of death vague or misattributed convulsions, brain fever, wasting disease, terms that could have described lead poisoning, but were more likely attributed to other causes in an era when occupational disease was poorly understood.

Then he found it.

Thomas Carelli, age nine, died April 17th, 1904.

Residents, [music] 49 Hanover Street.

Cause of death, acute poisoning.

Father, Jeppe Carelli.

Mother, Maria Carelli.

Daniel’s pulse quickened.

The address was two doors down from the Bellingham toy company.

The timing matched the photograph.

Taken in March, death in April.

The name matched the notation on the photograph’s reverse.

Master Thomas.

He searched for more information about the Carelli family.

The 1900 census showed Josephe Carelli, age 32, occupation laborer, Maria Carelli, age 28, and three children, Antonio, 6, Thomas, 5, and Rosa, 2.

By the 1905 census, the family had moved to a different address in the North End, [music] and Thomas was no longer listed.

Daniel found Juspice Carelli’s naturalization record from 1903.

[music] The family had immigrated from Naples in 1895, seeking the opportunities America promised.

Like thousands of other immigrant families, they’d found themselves trapped in poverty, [music] forced to send their children to work in order to survive.

He located a brief newspaper article from April 1904 in the Italian language newspaper Laazetta de Massachusetts.

>> [music] >> Justia, young victim of work.

Thomas Carelli, 9 years old, died after months of illness caused by his work in a toy factory.

Parents demand justice.

Daniel found the Italian translator to help him navigate the archives of Laazetta del Massachusetts.

The newspaper had covered the Carelli case extensively during the spring and summer of 1904, treating it as emblematic of the exploitation faced by immigrant families.

The translator, Maria Rosini, was a retired professor who had studied Italian-American history in Boston.

She met Daniel at the library, and together they worked through the fragile newspaper pages, carefully photographing each article before translation.

The first article dated March 25th, 1904 described Thomas Carelli’s deteriorating condition.

For 6 months, the boy has worked at Bellingham Toy Company painting wooden soldiers and horses.

His mother noticed his hands turning gray, his appetite disappearing.

He complains of stomach pain that leaves him crying in the night.

The doctor says his blood is poisoned by the pain he handles daily.

An article from April 1st, 1904 reported on Juspi Carelli’s confrontation with Edward Bellingham.

The father demanded his son be released from employment and compensation for medical expenses.

Bellingham refused, claiming the boy was free to leave at any time and that the illness was not related to factory work.

Children get sick, Bellingham reportedly said, “That is not my responsibility.” The article from April 20th, [music] 3 days after Thomas’s death, was longer and more detailed.

It described how Jeppe and Maria had taken Thomas to a photographer, Thompson’s studio on Salem Street, 2 weeks before he died.

The parents wanted documentation, the article explained.

They wanted proof of what the factory had done to their son.

The photograph shows Thomas holding one of the toy horses he had painted, his hands stained with the poison that killed him.

Maria [music] looked up from the translation, her eyes glistening.

They were trying to build a case.

[music] The photograph was evidence.

Daniel felt his throat tighten.

Did they succeed? She returned to the articles.

May 15th, 1904.

Jeppe Carelli has filed a complaint with the factory inspection department demanding an investigation into Bellingham toy company.

He presents the photograph of his dying son as evidence of the facto’s dangerous [music] conditions.

Inspector Henry Walsh has promised to review the case.

June 3rd, 1904.

Factory inspection completed at Bellingham Toy Company.

Inspector Walsh reports no immediate hazards found.

Recommends improved ventilation, but takes no enforcement action.

Jeppe Carelli calls the inspection a farce, claiming the factory was cleaned and workers sent home before the inspector arrived.

July 12th, 1904.

Carelli family continues fight for justice.

With help from the North End settlement house, Jeppe has contacted labor reform advocates.

The photograph of Thomas has been shown to city council members and newspaper editors.

My son should not have died for making toys, Jeppi [music] says.

But the final article dated September 8th, 1904 told the end of the story.

Carelli case dismissed.

City officials rule that insufficient evidence links Thomas Carelli’s death directly to factory employment.

Bellingham toy company continues operations.

The photograph that Juspe hoped would prove his case has been deemed not conclusive proof of causation.

Daniel contacted the North End Union, the modern successor to the North End settlement house mentioned in the 1904 articles.

The organization’s director, Frank Russo, was intrigued by Daniel’s research and offered access to the settlement houses historical records.

The archives were stored in a basement room, boxes of documents dating back to the organization’s founding in 1896.

Frank helped Daniel locate the files from 1904, pulling out ledgers that recorded the settlement houses activities, English classes, health clinics, legal aid services for immigrant families.

In a ledger dated May 1904, Daniel found an entry.

Jeppe [music] Carelli, assisted with translation of medical records and factory complaint, [music] family seeking justice for son Thomas, deceased from occupational poisoning, provided connection to reform league.

A folder labeled factory safety campaign [music] 1904 contained correspondence, petitions, and copies of newspaper articles.

Among them was a small envelope marked Carelli photographic evidence.

[music] Inside were two items.

A letter and a photographic print.

The letter written in Italian and translated into English by a settlement house worker was from Josephe Carelli.

To the members of the factory reform league, [music] I send you the photograph of my son Thomas taken 2 weeks before he died.

Look at his hands.

They are stained black from the paint he worked with every day for 6 months.

Look at his face.

You can see he is already dying.

He holds the toy horse he painted, one of thousands he made for children who will never know that a boy died to create their play thing.

I am not an educated man.

I came to America believing my children would have better lives than I had in Naples.

Instead, I watched my son slowly poisoned while making toys for the children of rich families.

The factory owner says this is not his fault.

The city inspector says there is no proof, but I have this photograph.

I have the truth.

Please help me make sure no other father has to watch his child die this way.

If you can do nothing else, keep this photograph.

Let people see what the factories are doing to our children.

Jeppe Carelli, May 1904.

The photograph was a copy of the one Daniel had been studying, but this print had notations written in margins, arrows pointing to Thomas’s hands with the word poisoning, circles around the dark circles under his eyes labeled malnutrition and toxicity, notes about the toy horse describing lead based paint, 50% plus lead content.

Frank looked over Daniel’s shoulder, reading the [music] letter.

Did the Reform League help him? Daniel pulled out more documents.

meeting minutes, campaign materials, petitions submitted to the city council.

The Reform League had taken up the Carelli case as part of a broader push for factory safety regulations, particularly for child workers.

They’d used Thomas’s photograph in pamphlets and presentations, showing it to politicians and journalists as evidence of the need for reform.

But the opposition was fierce.

Factory owners argued that regulation would destroy their businesses, that families needed the income their children brought home, that industrial accidents and illnesses were unfortunate but inevitable costs of progress.

The inspector’s report clearing Bellingham toy company had undermined the Reform League’s case, and without concrete proof linking Thomas’ death to his employment, the campaign stalled.

Sarah invited Daniel to present his findings at a medical history seminar at Boston University.

He prepared a presentation titled Death by Toy: Child Labor and Occupational Poisoning in Industrial Boston.

[music] Centering on Thomas Carelli’s story, but placing it within the broader context of industrial exploitation.

The seminar room was packed with students and faculty.

Daniel displayed the enlarged photograph of Thomas and the room fell silent as people absorbed the image, the dying child holding the toy that had killed him.

He walked them through his research, the factory records, the hospital admissions, the family’s fight for justice, [music] the reform league’s failed campaign.

He showed the letters, the newspaper articles in Italian and English, the inspector’s dismissive report.

He described how Jeppe Carelli had paid precious money for that photograph, hoping it would be proof enough to change a system that ground up children and called it progress.

[music] But the photograph wasn’t enough, Daniel said.

Because the power structure in 1904 Boston didn’t want to see what it showed.

Factory owners had political influence.

Inspectors were often corrupted or simply overwhelmed by the number of workplaces they were expected to monitor.

And immigrant families like the Carellis had no voice, no power, [music] no recourse.

A graduate student raised her hand.

What happened to the Bellingham toy company? Daniel pulled up another slide.

It continued operating until 1906 when a fire destroyed the workshop.

Edward Bellingham collected insurance money and opened a new factory in Cambridge.

That operation continued until 1918 when Massachusetts finally passed comprehensive child labor laws that made employing children under 14 in manufacturing illegal.

And the Carelli family, Jeppe, Maria, and their surviving children left Boston in 1906.

I found them in the 1910 census in Providence, Rhode Island.

Jeppe was working as a street vendor.

The children, Antonio and Rosa, were both in school, not working.

Whatever poverty they endured in Providence, Jeppe never sent his remaining children to factories.

Sarah added context about the medical understanding of lead poisoning at the time.

Physicians knew that lead was toxic, but the connection between chronic low-level exposure and severe poisoning was poorly understood.

Many doctors attributed children’s symptoms to other causes.

Poor nutrition, lack of fresh air, moral weakness of immigrant families.

The industrial medical establishment had strong incentives to minimize connections between workplace conditions [music] and disease.

After the seminar, several people approached Daniel with questions.

A professor of labor history asked if he’d found any evidence that Thomas’s case had influenced later reform efforts.

Daniel showed her documents from 1908 1910 indicating that reformers continued to reference the Carelli boy in their advocacy, though always as an anonymous case study rather than a named individual.

That’s how history often works.

The professor said individual tragedies become abstract data points.

The specific human story gets lost.

That’s why I wanted to identify him, Daniel replied.

To restore the name and face to the tragedy, Thomas Carelli wasn’t just a statistic in a public health report.

He was a 9-year-old boy who loved his family and died because their poverty made him expendable.

Daniel contacted the North End Union [music] again, proposing a small exhibition about child labor in Boston’s toy factories centered on Thomas Carelli’s story.

Frank Russo enthusiastically agreed, offering space in the organization’s community room for a month-long display.

Daniel worked with a local designer to create panels telling Thomas’ story alongside the broader historical context.

The centerpiece was the enlarged photograph of Thomas holding the toy horse surrounded by documents, the factory records, the reform league letters, Jeppe’s plea for help, the newspaper articles documenting the family’s fight.

They included a timeline showing the slow progress of child labor reform in Massachusetts.

The first factory inspection law in 1867, rarely enforced.

The establishment of a formal inspection department in 1886, underfunded and understaffed.

The 1888 law prohibiting employment of children under 13 in manufacturing, widely ignored.

And finally, the 1918 law that meaningfully restricted child labor with real enforcement mechanisms.

It took 14 years after Thomas’s death for Massachusetts to pass a law that might have saved him, Daniel wrote in the exhibition text.

And he was one of thousands.

[music] Between 1900 and 1920, hundreds of children in Boston alone died or were permanently disabled by occupational diseases and industrial accidents.

Most of their names are lost to history.

Sarah contributed a medical panel explaining lead poisoning, its symptoms, its long-term effects, its prevention.

She included historical and modern information, showing how the same lead compounds that killed Thomas were used in household paint until the 1970s, creating new generations of poisoned children before finally being banned.

The exhibition opened on a rainy Saturday in November.

To Daniel’s surprise, more than 50 people attended the opening event.

Several were descendants of Italian immigrants who’d lived in the North End during the early 1900s, drawn by publicity in the local Italian-American newspaper.

An elderly woman approached the photograph of Thomas studying it for a long time.

Finally, she turned to Daniel.

[music] “My grandfather worked in a toy factory,” she said quietly.

He never talked about it, but my mother told me he had scars on his hands from the chemicals.

He died young, 62, from something the doctors [music] called painters palsy.

I never knew what that meant until now.

Lead poisoning, Sarah said gently.

Chronic exposure causes neurological damage that manifests as tremors and paralysis.

It was common among people who worked with lead-based paints.

The woman nodded, tears in her eyes.

>> [music] >> He was one of the lucky ones.

I suppose he survived to adulthood.

This boy, she gestured to Thomas’s photograph.

He never had a chance.

Throughout the month, visitors left notes in a comment book.

Many shared family stories of child labor, dangerous working conditions, and the struggles of immigrant families trying to survive in an exploitative economic system.

Some expressed anger at the injustice.

Others wrote simply, “Thank you for remembering him.

Thank you for saying his name.” On the final day of the exhibition, Daniel stood alone in the community room, looking at Thomas Carelli’s photograph one last time before dismantling the display.

He’d spent 3 months researching this boy’s short life, tracing the threads of documents and records that preserved fragments of his existence.

He knew now that Thomas had been born in Boston in 1895, 2 months after his parents arrived from Naples.

He’d attended school sporadically until age 8 when his family’s poverty made his labor necessary for survival.

For 6 months, he’d worked at Bellingham Toy Company.

His small hands perfect for the delicate work of painting toy soldiers and horses with bright lead-based colors.

The work had paid 25 cents a day, about $8 in modern currency.

Not enough to lift his family from poverty, but enough that they couldn’t afford to lose it.

Thomas had painted thousands of toys in those 6 months, each one absorbing a little more lead into his bloodstream.

[music] He’d developed symptoms gradually, tiredness, stomach aches, headaches, but his parents had needed him to keep working.

By the time they understood how sick he was, the damage was irreversible.

Josephe Carelli had fought for justice with the limited tools available to him, official complaints, newspaper publicity, the photograph that documented his son’s condition.

But in 1904, Boston, an Italian immigrant laborer, had no power against factory owners, corrupt inspectors, [music] and a political system designed to protect industrial interests over human lives.

Yet, Jeppe’s fight hadn’t been entirely feudal.

The photograph he commissioned, the letters [music] he wrote, the testimony he gave to the Reform League, all had contributed to the eventual change.

Thomas’s story, anonymized, [music] had appeared in reform literature throughout the 1900s and 1910s.

While he received no individual credit, his suffering had been part of the accumulated weight of evidence that finally forced legislative action.

Daniel thought about the toy horse in the photograph.

The last thing Thomas had painted.

Somewhere perhaps that toy had been given to a child, played with, treasured, [music] eventually discarded, or lost.

That child would never have known the price paid for their play thing.

A 9-year-old boy’s life, slowly poisoned while creating something meant to bring joy.

He carefully packed the exhibition materials, making sure Thomas’s photograph was properly protected.

The image would return to the historical society’s archives, preserved and contextualized now, no longer anonymous.

Researchers in the future would be able to find Thomas Carelli to read his story, to understand what his death represented about an era when children were seen as expendable labor rather than lives deserving protection.

As Daniel locked the community room and stepped out into the cold December evening, he felt the weight of bearing witness.

Thomas Carelli had been dead for 120 years, but his story still mattered.

It testified to injustice, to the cost of unregulated capitalism, to the courage of families who fought against impossible odds for their children’s lives.

The photograph had preserved that testimony, waiting more than a century for someone to understand what it showed.

Not just a dying child with a toy, but evidence of a system that valued profit over human life.

documentation of a father’s desperate attempt to make his son’s death mean something.

Proof that even in the darkest moments of exploitation, [music] people fought back with whatever tools they had.

Thomas Carelli had died making toys, poisoned by the lead that made them bright and beautiful.

But his image had survived, and now his name would be remembered.

A small act of justice perhaps, but justice nonetheless.

In the end, Daniel thought that was what history could offer.

Not the power to change what had happened, [music] but the responsibility to ensure it wasn’t forgotten.

To bear witness to lives that deserve to be seen, named, and [music] mourned.

News

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

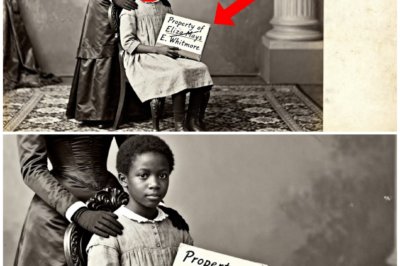

This 1868 Portrait of a Teacher and Girl Looks Proud Until You See The Bookplate

This 1858 studio portrait looks elegant until you notice the shadow. It arrived at the Louisiana Historical Collection in a…

End of content

No more pages to load