The truth behind this 1901 photo of two children is darker than it looks.

Daniel Price had spent 15 years collecting historical photographs of New England, building one of the most comprehensive private archives of turn of the century American life.

His Cambridge apartment was lined with carefully preserved images, farmers, shopkeepers, families on porches, children at play.

Each photograph was a window into a world that no longer existed.

and Daniel treated them with the reverence they deserved.

The estate sale in Lowel, Massachusetts, was advertised as containing miscellaneous historical items from the textile district.

Daniel arrived early on a Saturday morning in late September.

The autumn air crisp and promising.

The house belonged to the descendants of a man named William Bradford, who had worked as a supervisor at one of the city’s many textile mills in the early 1900s.

Most of the photographs were predictable.

factory exteriors, managers and formal poses, company picnics.

Then Daniel found a small tin box tucked behind a stack of ledgers.

Inside were a dozen loose photographs, unframed and uncataloged.

He handled each one carefully, studying the images under the natural light from the window.

The 11th photograph stopped him cold.

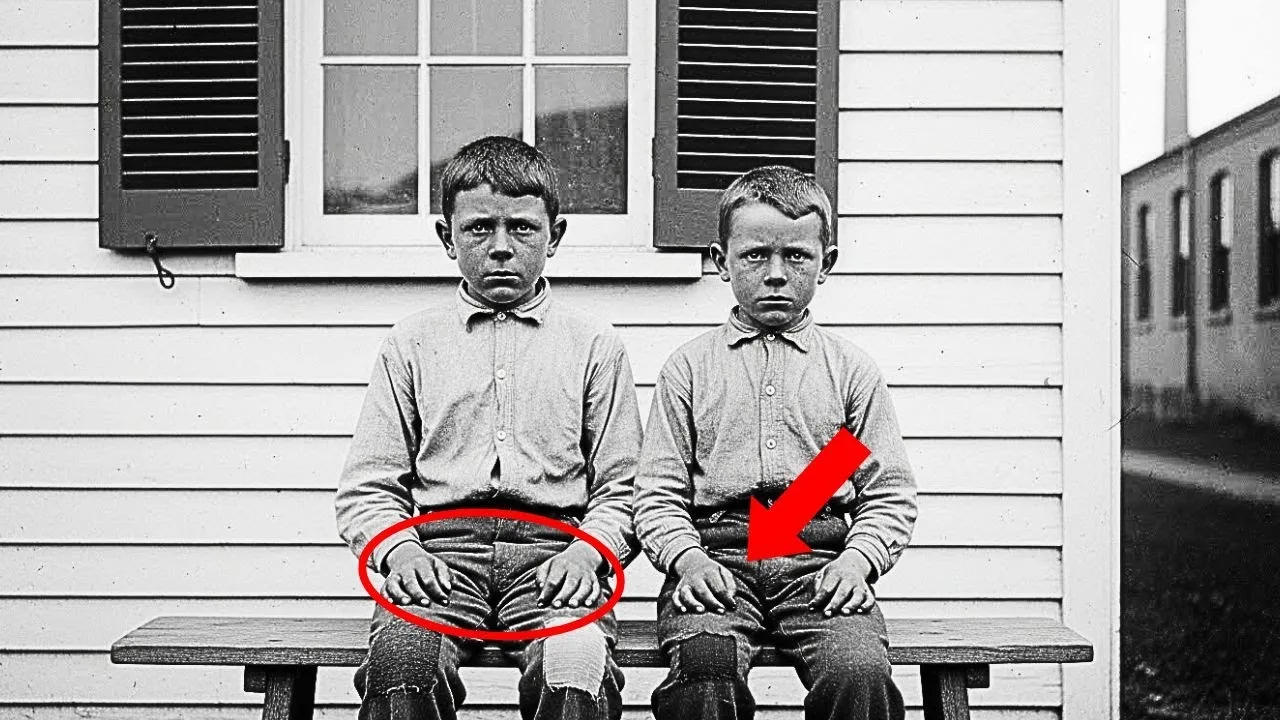

Two boys sat on a wooden bench in front of a simple white clapboard house.

The older boy appeared to be about 10, the younger perhaps eight.

Both wore rough work clothes, plain cotton shirts, and patched trousers too large for their thin frames.

Their faces were unnaturally serious, aged beyond their years with dark circles under their eyes.

But what caught Daniel’s attention was their posture.

Both boys held their hands in their laps in an awkward, unnatural position, as if unable to fully straighten their fingers.

Daniel turned the photograph over.

Written in faded pencil, mill workers, October 1901.

Evidence.

Below that, in different handwriting, never publish, destroy.

The word evidence sent a chill down his spine.

Evidence of what? And why had someone wanted this image destroyed yet kept it hidden for over a century? Daniel purchased the entire box of photographs for $20.

The seller, a middle-aged woman clearing out her late uncle’s belongings, seemed relieved to be rid of them.

“Just old factory pictures,” she said dismissively.

“Nothing interesting.” “But Daniel knew better.

This photograph was more than interesting.

It was a secret someone had tried very hard to bury.” Back in his apartment, Daniel set up his professional scanner and photography equipment.

He’d learned over the years that highresolution digital imaging could reveal details invisible to the naked eye.

Faded text, hidden signatures, layers of damage that told their own stories.

The photograph of the two boys deserved careful examination.

Under magnification, the image became even more disturbing.

The boy’s hands weren’t just awkwardly positioned.

They were deformed.

Their fingers curved inward like claws, the joints swollen and misshapen.

The older boy’s right thumb bent at an unnatural angle as if it had been broken and healed incorrectly.

The younger boy’s left hand showed visible scars across the palm and fingers.

Daniel zoomed in on their faces.

Both boys stared directly at the camera with expressions that haunted him.

Not quite defiant, not quite resigned, but something in between.

a kind of weary endurance that no child should possess.

Their clothing, which had appeared merely shabby at first glance, revealed itself under magnification to be covered in fine threadlike fibers.

Cotton dust, Daniel realized.

These weren’t just any workers.

They were textile workers.

He examined the background more carefully.

The White House behind them was modest, but well-maintained with shutters and a small covered porch.

Not a factory building or tenement, but an ordinary residence.

To the left edge of the frame, barely visible, was a portion of a larger brick building.

Industrial architecture unmistakably.

Daniel pulled out his reference books on Massachusetts textile mills and began cross-referencing the architectural style.

The brick pattern and window placement matched dozens of mills built in Lel between 1880 and 1905.

The city had been the heart of America’s textile industry, employing thousands of workers in massive factory complexes.

But child labor? Daniel knew it had been common in the early 1900s, but he’d never seen photographic evidence this stark, this personal.

Most images of child workers from the era were formal group portraits or propaganda photographs showing children in clean clothes performing light tasks.

This was different.

This was documentary evidence of something darker.

He returned to the notation on the back.

Evidence.

Evidence for what? A lawsuit, a news article, a reform campaign, and who had written never published destroy, the person who took the photograph, or someone who discovered it.

Later, Daniel picked up his phone and called Dr.

Sarah Chen, a labor historian at Boston University who specialized in industrial working conditions.

Sarah, I need your expertise on something.

How familiar are you with child labor in the Lowel Mills? Extremely, she replied.

Why? What have you found? Something that was meant to stay hidden.

Dr.

Sarah Chen arrived at Daniel’s apartment the next morning, her laptop bag heavy with research materials.

She was in her early 40s with sharp eyes that missed nothing and a reputation for meticulous historical investigation.

When Daniel showed her the photograph, she sat in silence for a full minute, studying every detail.

“Do you know what you have here?” she finally asked, her voice tight with emotion.

“Child laborers with injured hands,” Daniel replied.

“But I don’t know the context.” Sarah pulled out her laptop and opened a folder of scanned documents.

In the early 1900s, there was a movement of reformers, photographers, journalists, social workers, who were trying to expose the conditions in factories and mills.

The most famous was Lewis Hine, who documented child labor across the country.

But there were others less known, who worked locally and often in secret.

We She showed Daniel a series of photographs similar to his.

children in factories, mines, and caneries.

Their faces exhausted, their bodies marked by labor.

The factory owners fought back hard.

They banned photographers from their premises, threatened lawsuits, even had some reformers arrested for trespassing.

Many photographs were confiscated and destroyed.

So, this might have been taken by a reformer, Daniel asked.

Almost certainly.

The notation evidence suggests it was meant for legal proceedings or publication, but someone, probably a factory owner or manager, seized it and tried to suppress it.

Sarah zoomed in on the boy’s hands.

These deformities are consistent with what we know about textile work.

Children as young as six were employed as doers.

They’d crawl under operating looms to replace empty bobbins with full ones.

The machinery never stopped.

fingers got caught, crushed, mangled.

The children worked 12 to 14-hour days in conditions that permanently damaged their bodies.

Daniel felt sick.

These boys were how old? 8, 10.

Probably started working at 6 or 7.

By the time they were the ages in this photo, they’d already spent years in the mills.

Sarah examined the White House in the background.

This is interesting.

They’re not photographed inside the factory, which makes sense.

the reformer wouldn’t have been allowed in.

But why in front of this specific house? Daniel had been wondering the same thing.

Maybe it’s where they lived.

Possibly.

Or maybe it’s significant for another reason.

Sarah made notes in her laptop.

I need to access the city records for Lel in 1901.

Property records, census data, mill employment logs if any survived.

We need to figure out who these boys were, who took this photograph, and what happened to them.

The hands, Daniel said quietly, unable to look away from the image.

Their children, and their hands are destroyed.

Sarah’s expression was grim.

That’s what made child labor so profitable.

Children’s hands were small and nimble, perfect for reaching into machinery and performing delicate tasks.

But those same small hands were also fragile.

easily broken, easily maimed.

The factory owners considered it an acceptable cost of doing business.

The Lowel Historical Society occupied a converted mill building.

Its brick walls a reminder of the city’s industrial past.

Sarah had arranged access to their archives, and she and Daniel spent two days combing through census records, city directories, and property deeds from 1900 to 1902.

The breakthrough came from the 1900 census.

Sarah found a cluster of families living on Chapel Street, just blocks from the largest textile complex in Lel.

One household stood out, a white Clapboard house numbered 47, owned by a widow named Mrs.

Catherine Murphy, who took in borders, mostly mill workers and their families.

Living in that house in 1900 were two boys who matched the approximate ages in the photograph.

James Murphy, age nine, listed as Mrs.

Murphy’s grandson and Peter Kowalsski age seven listed as a border.

Both boys occupation was recorded as mill worker.

9 and 7 years old.

Daniel whispered staring at the census page.

Working in the mills.

Sarah was already searching for more information.

She found James Murphy’s birth record.

Born in Lel in 1891 to Mary Murphy who died in childbirth.

Father unknown or not recorded.

James had been raised by his grandmother, Catherine, after his mother’s death.

Peter Kowolski’s story was even more heartbreaking.

He was listed in the 1900 census as a border, but Sarah found an earlier record from 1895, an immigration manifest.

Peter had arrived at Ellis Island at age 2 with his parents, Polish immigrants seeking work in America’s factories.

His father died in 1898 in a mill accident.

His mother remarried and moved to New York, leaving Peter in the care of Mrs.

Murphy.

Whether this was abandonment or an arrangement meant to be temporary, the records didn’t say.

So, they weren’t brothers, Daniel said.

Just two boys living in the same boarding house, working in the same mills.

Sarah found employment records from the Appleton Mill, one of Lel’s largest textile factories.

The records were incomplete.

Many had been lost or destroyed over the decades.

but fragments remained.

James Murphy was listed as hired in March 1897 at age 6 as a dooffer.

Peter Kowalsski hired in July 1898.

Age five, also as a dooffer.

The job description made Daniel’s stomach turn.

Doers remove full bobbins from spinning frames and replace them with empty ones.

Must be small enough to move quickly between machinery.

Work performed while machinery is in operation.

payment $2.50 per week.

$2.50 per week for a child crawling under operating machinery that could crush or mangle them at any moment.

And they’d been doing this for years before the photograph was taken.

Sarah found one more document, a letter dated September 1901, addressed to the Massachusetts State Labor Inspector from someone named Thomas Wittmann.

The letter complained about child labor conditions at the Appleton Mill, specifically mentioning boys as young as five working 14-hour days with frequent injuries.

The letter requested an investigation.

Thomas Wittmann, Sarah said, searching her database.

I know that name.

He was a reformer.

Worked with several labor organizations in the Boston area.

Took photographs of working conditions to support legislative campaigns.

He took this photograph, Daniel said with certainty.

He was building evidence for his complaint.

Thomas Wittman’s papers were housed at the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston, part of a larger collection on early labor reform movements.

Sarah and Daniel obtained research access and spent a full day examining boxes of correspondents, newspaper clippings, and photographic negatives.

Wittmann had been a teacher turned activist, horrified by the conditions he witnessed in factories where former students worked.

Starting in 1899, he began documenting child labor throughout New England, taking photographs and collecting testimonies.

His goal was to provide evidence for stronger labor laws, particularly regulations limiting the working age and hours for children.

His personal journal dated October 1901 contained an entry that made everything clear.

Visited Lel today to document conditions at Appleton Mill.

Management refused entry as expected.

Contacted Mrs.

Catherine Murphy, who operates a boarding house for mill workers.

She agreed to allow me to photograph two of the boys in her care, James and Peter, on the condition I not use their full names in any publication to protect them from retaliation by the mill owners.

The entry continued, “The boy’s hands are in terrible condition.

James’ right thumb was crushed 6 months ago when he reached too far into a spinning frame.

The mill doctor said it, but it healed crookedly.” Peter has scars from when cotton threads became tangled around his fingers, cutting deeply before the machine could be stopped.

Both boys can no longer fully straighten their fingers.

Permanent deformities from repetitive motion and injury.

They are 9 and 7 years old.

This is unconscionable.

Wittmann described photographing the boys on the front porch of Mrs.

Murphy’s house, choosing the location because the white clapboard exterior would provide good contrast and the natural light was better than inside.

The brickmill building visible at the edge of the frame was deliberate.

Wittmann wanted to show the proximity between the children’s living quarters and their workplace.

The photograph was meant to be included in a report to the state legislature along with dozens of other images documenting child labor conditions, but the report was never completed.

In November 1901, just weeks after taking the photograph, Wittman’s papers contained increasingly worried entries, received threatening letter from Appleton Mills Legal Council demanding I cease my investigations and surrender all photographic evidence.

They threaten legal action for trespass and defamation.

A later entry dated December 1901.

My photographs have been confiscated.

Mill representatives, accompanied by a police officer, arrived at my home with a warrant, claiming the images were obtained through illegal trespass and constitute proprietary information about mill operations.

I was forced to surrender my negatives and prints.

The investigation is over before it could truly begin.

But Wittmann had kept one photograph, the image of James and Peter.

A final entry explained why.

I hid the photograph of the Murphy house children as it was not taken on mill property and thus not covered by the warrant.

I will keep it safe, evidence of what these children endure.

Someday, when the law is stronger, it may still serve justice.

The confiscation of Wittman’s photographs had been orchestrated by the Appleton Mills management, working with local authorities who were sympathetic to the factory owners.

Sarah found the paper trail in the Lowel City Hall archives.

a complaint filed by the mill’s legal department against Thomas Wittmann for industrial espionage and defamation.

The complaint alleged that Wittmann had trespassed on mill property, photographed proprietary manufacturing processes, and was planning to publish false and malicious claims about working conditions.

The mill demanded the seizure of all photographs and notes and requested that Wittmann be prohibited from coming within 500 ft of any Appleton Mill facility.

A sympathetic judge, who Sarah discovered owned stock in the Appleton Mill Company, had granted the warrant.

Wittman’s collection of evidence was confiscated and destroyed with the exception of the one photograph he’d managed to hide.

But Sarah found something else in the archives.

Internal mill correspondents from late 1901, including a memo from the mill superintendent to the board of directors.

The memo marked confidential, discussed Whitman’s investigation.

The reformer has been neutralized.

His photographic evidence has been seized and destroyed.

However, we must acknowledge that the conditions he documented while legal under current statutes present a public relations risk if exposed through other channels.

The memo went on to recommend modest changes.

Increase the minimum working age from 5 to 8 years.

Reduce daily hours from 14 to 12 for workers under age 14.

Implement a reporting system for serious injuries to demonstrate our commitment to worker safety.

These changes will cost the company approximately $3,000 annually, but will protect us from future scrutiny.

Daniel felt a surge of anger.

They knew.

They knew the conditions were terrible and they only changed them to protect their reputation, not because they cared about the children.

Sarah showed him another document, a letter from the mills legal council to the superintendent, dated January 1902.

I recommend we identify all children photographed by the reformer and relocate them to other positions or facilities.

If questions arise later about the welfare of these specific individuals, we can truthfully state they are no longer employed in the positions documented.

This will undermine any future claims about working conditions.

They were going to hide the evidence by moving the children, Sarah said grimly.

Scatter them to different mills or fire them entirely so no one could verify Wittman’s documentation.

Daniel thought of James and Peter, two boys whose only crime was being born into poverty.

now being moved around like chess pieces to protect the corporation’s image.

Did they succeed? Were the boys relocated? Sarah pulled up employment records.

James Murphy disappears from the Appleton Mill records in February 1902.

Peter Kowalsski’s last recorded payment is March 1902.

After that, nothing.

They either moved to different mills, left Lel entirely, or she trailed off, not wanting to voice the darker possibility.

The Lel General Hospital archives contained patient records dating back to the 1880s, though many files were incomplete or had been lost to water damage and deterioration.

Sarah had obtained special permission to access records related to industrial accidents, hoping to find treatment records for James and Peter.

What she found was worse than she expected.

The hospital maintained a ledger of all patients admitted or treated in their emergency clinic organized by date.

In September 1900, 13 months before Wittman’s photograph, there was an entry.

James Murphy, age 8, right thumb crushed in spinning frame, bone set, wound cleaned, sent home with instructions for rest.

Payment, mill company insurance.

Another entry from April 1901.

Peter Kowalsski, age seven.

Deep lacerations to left hand from tangled threads.

15 stitches required.

Sent home.

Payment.

Mill company insurance.

These matched Witman’s description in his journal.

But there were more entries.

November 1901.

James Murphy, age 9.

Exhaustion and malnutrition.

Advised bed rest and improved diet.

Patient unable to afford treatment.

No payment received.

December 1901.

Peter Kowalsski, age 8.

Respiratory distress consistent with chronic dust inhalation.

Recommended removal from mill environment.

Patient returned to work against medical advice.

The hospital records painted a devastating picture.

Repeated injuries, chronic health problems, and a system where children were patched up just enough to send them back to the machines that had hurt them.

The mill company insurance covered acute injuries, but nothing else.

No preventive care, no treatment for the long-term effects of the work.

Daniel found another set of records, these from a private physician named Dr.

Albert Hastings, whose papers had been donated to the historical society.

Dr.

Hastings had kept detailed notes on his patients, including several mill workers.

In February 1902, he wrote, “Examine James Murphy, age 10, at the request of his grandmother.

The boy’s right hand shows permanent deformity from poorly healed fracture.

His respiratory system is compromised from cotton dust exposure.

His growth is stunted.

He appears 2 years younger than his actual age.

I advise Mrs.

Murphy to remove the boy from mill work immediately, but she states the family cannot survive without his wages.

This is the tragedy of our industrial system.

We sacrifice our children for profit.

A similar entry from March 1902 described Peter.

The Kowalsski boy is in even worse condition.

Scars across both hands, chronic cough, signs of early arthritis in his finger joints at age 8.

He is illiterate, never having attended school.

When I asked about his parents, he became quiet and withdrawn.

Mrs.

Murphy explains his mother abandoned him.

His father is dead.

The boy has nowhere to go except back to the mill that is destroying him.

Sarah sat back in her chair, tears in her eyes.

They were trapped.

These boys had no choice, no escape, no future except more of the same until their bodies gave out completely.

Tracing what happened to James and Peter after 1902 proved nearly impossible.

They vanished from Lel’s records completely.

No census entries, no employment records, no hospital admissions.

It was as if they’d simply ceased to exist.

Sarah expanded her search, looking at records from surrounding towns and other mill cities in Massachusetts.

In Lawrence, 30 mi from Lel, she found a possible lead, a James Murphy listed in the 1905 city directory as a textile worker at the Everett Mill.

age would be approximately 14.

But with no other identifying information, Sarah couldn’t be certain it was the same person.

Daniel searched death records, dreading what he might find, but knowing it was necessary.

In Lel’s cemetery records from 1903, he found an entry that made his heart sink.

Peter Kowalsski, aged 10, died March 17th, 1903.

Caused tuberculosis and respiratory failure.

Buried Lowel City Cemetery Poppers section.

No marker.

10 years old.

Peter had died at 10.

His lungs destroyed by cotton dust and disease.

His hands permanently damaged from machinery.

His childhood stolen entirely.

And he’d been buried in an unmarked grave, one of countless poor children whose deaths were recorded but not remembered.

Sarah found the death certificate which provided more detail.

Peter Kowalsski, white male, age 10.

Occupation, mill worker.

Residence: Murphy boarding house, Chapel Street.

Cause of death, tuberculosis complicated by industrial pneumoconeiosis.

Cotton lung, attended by Dr.

A.

Hastings.

Body claimed by Katherine Murphy.

Industrial pneumoconeiosis, the medical term for lungs destroyed by inhaling cotton fibers day after day, year after year.

Peter had been breathing that dust since age 5.

7 years of exposure had killed him.

Daniel and Sarah visited Lel City Cemetery, walking through the poppers section where those too poor for proper burials were interred.

The area was overgrown, the few markers that existed weathered and illeible.

There was no way to know which unmarked plot held Peter’s remains.

“He deserved better than this,” Daniel said quietly, standing among the weeds and forgotten graves.

“They both did.” Sarah’s research into James Murphy continued.

She found a marriage record from 1910 in Lawrence.

James Murphy married to Emma Walsh.

In the 1910 census, he was listed as a laborer, no longer working in textiles.

The census noted he was disabled, unable to perform mill work due to hand injuries.

Sarah tracked him through city directories and sparse records.

He’d worked various jobs, warehouse loader, street cleaner, night watchman, positions that didn’t require fine motor control.

He and Emma had three children between 1911 and 1917.

Then in 1918, Sarah found his name in military draft registration records.

James Murphy, age 27, registered but marked 4F, physically unfit for service due to hand deformities and respiratory condition.

The same injuries from his childhood had followed him into adulthood, marking him as damaged, unable even to serve his country in wartime.

The trail ended in 1942 with James’s death certificate.

James Murphy, age 51, died of heart failure.

survived by wife Emma, children Robert, Mary, and Thomas.

51 years old, young by modern standards, but he’d lived longer than Peter.

Whether that was mercy or simply prolonged suffering, Daniel couldn’t say.

Sarah wrote to James Murphy’s descendants, hoping someone in the family had survived to the present day.

After several weeks, she received a response from a woman named Linda, who identified herself as James’s granddaughter, the daughter of his son, Thomas.

They met at a coffee shop in Lawrence.

Linda was in her 60s, a retired teacher with her grandfather’s dark eyes.

She’d brought a small box of family photographs and documents.

I never met my grandfather, James,” Linda began.

He died when my father was just 20, but my father talked about him constantly.

He said grandfather’s hands were twisted that he could barely hold a pen or button his own shirt.

My father always wondered what had happened, but grandfather refused to talk about his childhood.

He’d only say that he’d worked in the mills and that it had cost him everything.

Linda showed them a photograph from the 1930s.

James as an adult standing with his family.

Even in the grainy image, his hands were visible, fingers curved inward, just as they’d been in Wittman’s 1901 photograph.

30 years later, the deformities remained.

My father said grandfather had nightmares his whole life.

He’d wake up screaming about machines, about hands getting caught, about a boy named Peter who died.

My father thought Peter was grandfather’s brother, but we could never find any record of him.

Daniel felt his throat tighten.

Peter wasn’t his brother.

They were friends, lived in the same boarding house, worked in the same mill.

Peter died when he was 10 years old.

Linda’s eyes filled with tears.

He remembered all those years.

He remembered his friend who didn’t survive.

Sarah showed Linda the 1901 photograph of James and Peter sitting on the bench, their damaged hands visible, their faces prematurely aged.

Linda stared at it for a long moment, then gently touched the image of her grandfather as a boy.

“He was 9 years old here,” she whispered.

“Just nine and already broken.” Linda told them what she knew of James’ later life, how he’d struggled to find work, how he’d been ashamed of his hands, how he’d insisted all his children finish school and never ever work in factories.

He used to say, “I gave my hands so you wouldn’t have to.” My father became a teacher because of that.

I became a teacher because of him.

We all did, all the grandchildren.

It was our way of honoring what he sacrificed.

She pulled out one more item from her box, a diary that had belonged to James, kept sporadically over the years.

Linda opened it to an entry from 1925.

Today would have been Peter’s 33rd birthday.

I think of him often.

Wonder what kind of man he would have become if the mills hadn’t killed him.

We were just children doing what we had to do to survive.

But children shouldn’t have to survive.

They should get to be children.

I look at my own son, age seven, the same age Peter was when I first met him.

My son’s hands are smooth and unmarked.

He goes to school, plays with friends, doesn’t know what cotton dust tastes like.

This is what I wanted.

This is why I endured.

Daniel stood before an audience of historians, labor advocates, and descendants of mill workers at the Lel National Historical Park.

The restored photograph of James and Peter was projected on a large screen, their faces and damaged hands visible in painful detail.

Sarah sat in the front row, Linda beside her, both of them there to witness the unveiling of a story that had been hidden for 123 years.

In October 1901, Daniel began, a reformer named Thomas Wittmann took this photograph as evidence of child labor abuses in Massachusetts textile mills.

Two boys, James Murphy and Peter Kowalsski, ages nine and seven, sat on a bench in front of their boarding house.

Both had been working in the mills since they were 5 or 6 years old.

Both had suffered permanent injuries to their hands from the machinery they operated 12 to 14 hours a day.

He advanced to the next slide, showing close-ups of their deformed fingers.

The audience shifted uncomfortably, confronted with the physical evidence of what industrial exploitation had done to children’s bodies.

Thomas Wittmann wanted to use this photograph to advocate for stronger labor laws, but the mill owners seized most of his evidence and had him legally prohibited from continuing his investigation.

This photograph survived only because Wittmann hid it, knowing that someday it might still serve the cause of justice.

Daniel showed documents.

The mill’s internal memos acknowledging the dangerous conditions.

The medical records detailing repeated injuries.

The death certificate for Peter Kowalsski.

Dead at age 10 from lungs destroyed by cotton dust.

Peter never got to grow up.

He never learned to read, never had a childhood, never had a chance.

He died in 1903 and was buried in an unmarked grave, one of countless children’s sacrificed to industrial profit.

Sarah stood to add historical context.

The conditions these boys endured were legal.

Child labor wasn’t effectively regulated in Massachusetts until 1913 when new laws finally raised the minimum working age and limited hours.

Even then, enforcement was weak.

It wasn’t until federal legislation in the 1930s that child labor in factories was truly curtailed.

She gestured to the photograph.

But we shouldn’t need laws to tell us that children deserve protection.

These boys destroyed hands, their exhausted faces, their stolen childhoods.

This should have been enough.

The fact that it wasn’t, that millowners confiscated evidence and silenced reformers, tells us something important about how power protects itself.

Linda stepped forward, her voice shaking, but determined.

My grandfather James survived.

He lived to age 51, married, had children, built a life despite the damage done to him.

But he never forgot Peter.

He carried the guilt of survival, wondering why he lived when his friend died.

He made sure his children and grandchildren never had to work as he did.

That was his way of honoring Peter’s memory, ensuring that their suffering meant something.

Daniel brought up the final slide, a modern photograph of Lel City Cemetery’s Popper section, overgrown and forgotten.

Peter Kowalsski has no marker, no memorial.

His grave is lost among dozens of others.

But this photograph preserves him.

It proves he existed, that he mattered, that what was done to him was wrong.

The audience sat in heavy silence.

Then someone asked the question Daniel had been waiting for.

What can we do? Remember, Daniel said simply, tell their stories.

When you look at old photographs of industrial America, of factories and progress and prosperity, remember the children who paid the price.

Remember James and Peter.

Remember that the comfortable present we enjoy was built partly on the broken bodies of children who had no choice and no voice, Sarah added.

And remain vigilant.

Child labor hasn’t disappeared.

It’s moved to other countries, other industries.

The same economic forces that put James and Peter under those machines still exist.

The same willingness to exploit the vulnerable for profit still exists.

These boys story isn’t just history.

It’s a warning.

Linda placed a hand on the podium, steadying herself.

My grandfather wanted people to know.

That’s why he kept that diary.

Why he told my father stories even though they haunted him.

He wanted the truth to be told even if it was painful.

especially because it was painful.

After the presentation, Daniel, Sarah, and Linda drove to Lel City Cemetery.

They’d arranged for a memorial marker to be placed in the Poppers section, even though Peter’s exact grave was unknown.

The marker read, “In memory of Peter Kowalsski, 1893 1903, and all the children who labored and died in the mills of Lel, may their sacrifice never be forgotten.” As they stood before the marker, Daniel thought about the photograph that had started this journey.

An image meant to be destroyed, hidden away by someone who wrote, “Never publish on the back.” But secrets have a way of emerging, especially when they carry truth that demands to be told.

The photograph of James and Peter would be displayed at the Lel National Historical Park, properly contextualized and preserved.

Their story would be taught, their suffering acknowledged, their humanity restored.

It had taken 123 years, but the evidence Thomas Wittmann fought to preserve had finally served justice.

The truth behind that 1901 photograph was darker than it looked.

Two children with destroyed hands, trapped in a system that valued profit over life, their futures stolen before they’d barely begun.

But there was also light in that darkness.

James’ survival and his determination to protect future generations.

Sarah’s dedication to uncovering hidden histories and the simple fact that people still cared enough to listen, to remember, to honor the children who suffered.

As the autumn wind rustled through the cemetery, carrying with it the scent of fallen leaves and approaching winter, Linda whispered, “Rest now, Peter.

Someone finally knows your name.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load