The Truth Behind This 1898 Family Photo Is More Tragic Than Anyone Imagined

The autumn rain drumed against the windows of the conservation lab on Newbury Street, casting shifting shadows

across Sarah Mitchell’s workbench.

At 34, she had restored hundreds of photographs.

Dgeray types from the Civil

War era, faded tin types of immigrant families, crumbling album prints that smelled of time itself.

But the photograph that arrived that Tuesday morning in October felt different.

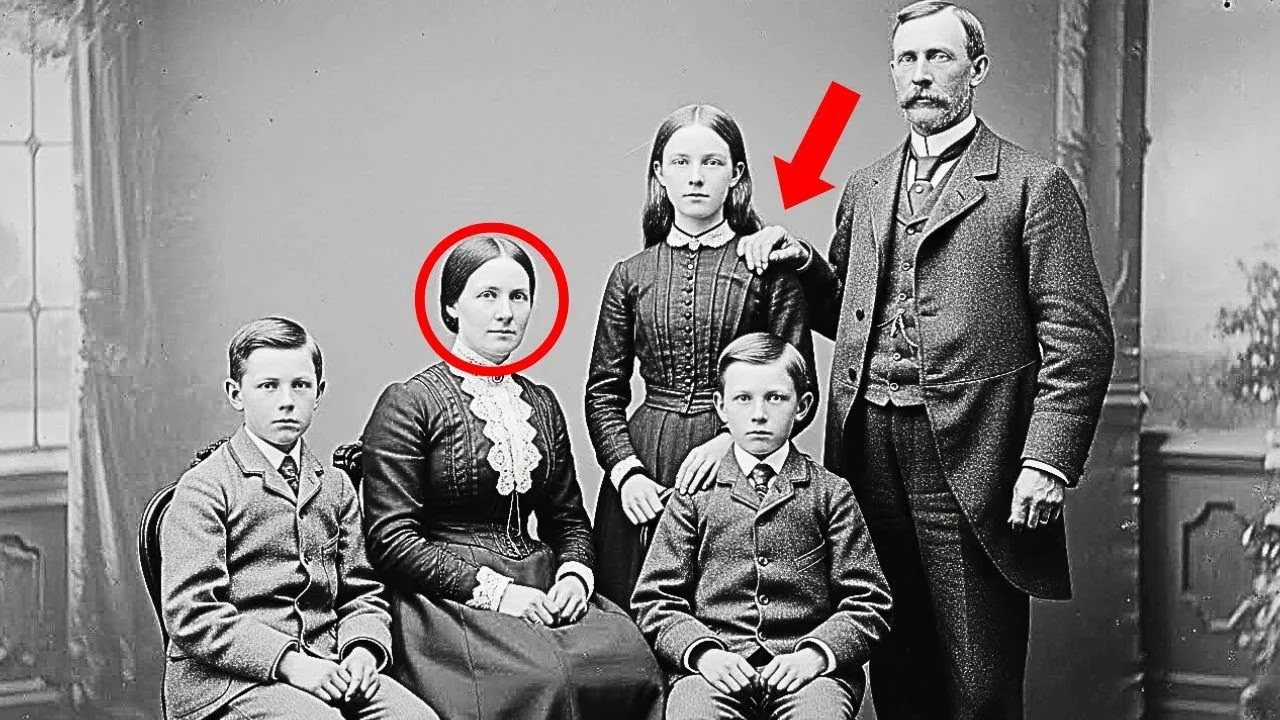

The image showed a family of

five posed in what appeared to be a photographers’s studio.

The year 1889

was penciled on the back in faded graphite.

A bearded man in a dark suit stood behind a seated woman whose

elaborate dress suggested modest prosperity.

Three children arranged themselves around their parents.

Two

boys in matching sailor collars flanking their mother and a girl of perhaps 14 standing beside her father.

Sarah

adjusted the magnifying lamp, studying the composition.

Victorian family portraits followed predictable patterns.

Rigid postures, unsmiling faces, the formal distance that characterized an era when photography still felt like

capturing one’s soul.

Yet something about this particular arrangement nagged at her professional instincts.

The

father’s right hand rested on his daughter’s shoulder, but the placement seemed deliberate beyond mere affection.

His fingers weren’t simply touching her dress.

They pressed into the fabric with visible intention.

Each digit positioned

with what looked like careful purpose.

The daughter’s face showed the faintest tension around her eyes, a tightness in

her jaw that suggested she was holding something back.

She photographed the image at high resolution, zooming in on

details.

The father’s expression was stern but not unkind.

The mother sat

with perfect posture.

Her hands folded precisely in her lap, but there was something unsettling about her vacant

stare.

Her eyes seemed to look past the camera rather than at it.

The two boys showed typical restlessness.

One had slightly blurred features suggesting movement during the exposure.

But the daughter remained perfectly still, her body language speaking volumes that Sarah couldn’t quite

translate.

She stood close to her father, almost leaning into him, seeking shelter, perhaps.

As afternoon light

faded, Sarah found herself returning again and again to that hand on the shoulder.

Victorian fathers rarely

displayed such physical affection in formal portraits.

This hand was communicating something specific,

intentional.

Each finger pressed down in what almost looked like a sequence or pattern.

A message waiting to be

understood across more than a century of silence.

By morning, Sarah had contacted the client who’d submitted the

photograph, a woman named Helen Richards, who’d inherited it from her grandmother’s estate.

Helen knew little

about the image beyond a family story that it depicted her great great grandparents, but she agreed to meet

Sarah at the lab that afternoon.

Helen arrived at 2:00.

A retired

librarian in her late60s with silver hair and intelligent eyes.

She studied

the photograph with curiosity and sadness.

“My grandmother never talked much about this side of the family,” she

explained.

“I found this in a box after she passed.

It was wrapped separately, almost hidden.” Sarah showed Helen the

highresolution images on her computer screen.

“I need to ask something unusual.

Do you know if anyone in your

family history was deaf or heart of hearing? Helen’s eyes widened.

Actually,

yes.

My grandmother’s mother.

She would have been the daughter in this photo.

She was deaf from childhood.

A fever

when she was about four or five.

Why? Sarah zoomed in on the father’s hand.

Because I think your great great grandfather is speaking to his daughter in this photograph.

Look at the finger

placement.

It’s not random.

For the next hour, Sarah explained her theory.

During

the late 19th century, before American Sign Language became widespread, many families with deaf members developed

their own systems of tactile communication.

Patterns of touches and finger positions that conveyed meaning

through touch rather than sight or sound.

Helen leaned closer to the screen, her breath catching.

I never

knew.

Grandmother never mentioned this.

Sarah had spent the previous evening researching historical tactile

communication methods.

The pattern of the father’s fingers, thumb pressed down, index finger extended, middle and

ring fingers curved, pinky pressed firmly, resembled documented finger spelling positions, but with variations

suggesting a family specific system.

Can you translate what he’s saying? Helen

asked, her voice tight with emotion.

Not exactly, but I have a colleague who studies historical deaf education.

She

might help.

Sarah paused.

There’s something else.

The mother’s expression.

It’s unusual.

Most women in formal portraits showed some emotion.

She looks completely disconnected.

Helen nodded slowly.

There was a story, very vague, that someone on that side

had been troubled.

Mental illness wasn’t discussed openly.

Then Sarah pulled up

another magnified section.

The mother’s hands clasped so tightly the knuckles showed white even in sepia tones.

Beside

her, one young son leaned slightly away, his small hand gripping the chair arm as

if steadying himself.

Would you let me investigate further? Sarah asked.

I’d

like to trace the family’s history.

See what records exist.

Helen touched the photograph gently.

Maybe it’s time

someone understood why grandmother kept this hidden.

The Massachusetts Historical Society occupied a stately

building on Boilston Street.

Its archives holding countless fragments of Boston’s past.

Sarah approached the

research room that Friday morning with particular anticipation.

The society’s collection included business records

from several 19th century photography studios, including Wittman and Sons.

The

archivist, Thomas Chen, greeted her warmly.

At 53, he’d spent three decades

helping researchers navigate the collections.

Victorian photography studios were

surprisingly meticulous, he said, pulling leatherbound ledgers from climate controlled stacks.

Every sitting

was recorded.

Date, time, client name, number of exposures, special requests.

Sarah settled at a research table pulling on cotton gloves before opening the first ledger.

The handwriting was

cramped but legible.

entries organized chronologically.

She started with January 1889, scanning

each page carefully through spring months filled with mundane yet fascinating entries.

Then in the ledger

dated June 1889, she found it.

The Harrison family, father, mother, three

children, special arrangement requested, one exposure only, payment in advance.

Note: Father specified no retouching.

Sarah’s pulse quickened.

She

photographed the entry, noting the date, June 15th, 1889.

The special arrangement notation was unusual.

Most families wanted multiple exposures, and retouching was standard

practice.

Thomas appeared at her shoulder.

Found something? The Harrison

family.

Are there other records? City directories, census records, newspaper archives.

They worked together for 2

hours piecing together fragments.

The 1890 census showed James Harrison, age

42, clerk at a shipping firm.

His wife Catherine, 38, children, Emma, 14,

Robert, 10, Thomas, 8.

Wait, Thomas said, pulling up another document.

There’s a notation in institutional records.

Catherine Harrison, admitted to Boston Lunatic Hospital in June 1889,

days after this photograph.

Sarah felt a chill.

Can we access those records? Not

easily.

Medical records from that period are restricted, but newspaper archives might help.

The Boston Globe Archives

revealed fragments.

A brief notice dated June 18th, 1889.

Commitment proceedings.

Mrs.

Katherine Harrison of Southoun committed to Boston Lunatic Hospital following petition by

husband.

Witnesses testified to episodes of dangerous behavior.

Children removed

from household for safety.

Sarah sat back, pieces forming a picture.

He was

protecting them.

The photograph was taken right before he had her committed.

Doctor Rebecca Stern’s office at the

Perkins School for the Blind overlooked a courtyard where students moved between classes.

At 49, Rebecca had devoted her

career to studying the history of tactile communication, particularly the informal systems families developed

before standardized methods existed.

Sarah spread the highresolution images

across Rebecca’s desk.

“I need your expertise on something that might be remarkable.” Rebecca examined the

photographs through a magnifying glass, her expression intensifying as she studied the father’s hand position.

This

is tactile signing, she said after several minutes.

Not formal, too

idiosyncratic, but definitely intentional communication.

She pulled out a reference book filled with

historical illustrations of finger positions.

In the 1880s, there was no single unified system for deaf education

in America.

Many families developed their own codes.

These were usually modifications of finger spelling

alphabets combined with agreed upon gestures.

Can you interpret what he’s saying? Sarah asked.

Rebecca positioned

her own hand in the same arrangement as James Harrison’s, feeling the position of each finger.

It’s difficult without

knowing their specific system, but certain patterns appear across multiple families.

The thumb and pinky pressed

down while other fingers are positioned differently.

That often indicated urgency or importance.

The middle and

ring fingers curved in this particular way.

She paused, consulting references.

In several documented systems, this configuration meant quiet or silent.

Sarah felt her throat tighten.

He’s telling her to stay quiet, possibly, or

to stay calm, to be safe.

These hand positions often carried emotional weight beyond their literal meaning.

A father

touching his daughter this way while having their photograph taken.

He’s trying to comfort her while conveying a

message.

Rebecca looked up.

What’s the context? Sarah explained what she’d discovered

about Catherine Harrison’s commitment to the asylum, the sale of the house, the family’s disappearance from Boston

Records.

Rebecca listened intently, occasionally making notes.

“This photograph was taken

3 days before the commitment hearing.” Sarah said he would have known what was coming.

Rebecca set down her magnifying

glass.

Then this wasn’t just a family portrait.

It was a farewell and a

message.

He was preparing his daughter for what was about to happen, telling her how to respond.

Stay quiet.

Stay

safe.

Don’t fight what’s coming.

They examined every detail through the lens

of tactile communication.

Rebecca pointed out how Emma’s body language, standing close to her father,

her own hand positioned as if ready to receive another message, suggested fluency in this silent language.

The

American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut, maintained archives dating back to its founding in

1817.

Sarah made the drive on a gray Saturday morning.

The school’s historian,

Margaret Walsh, had agreed to search their records for any student named Emma Harrison.

Margaret met Sarah in the

archive room.

a converted library smelling of old paper and preservation materials.

We have enrollment records

for every student who attended between 1817 and 1920, she explained, pulling

out index cards organized by decade.

They searched methodically.

After 2

hours, Margaret found it.

Harrison Emma enrolled September 1889.

Age 14.

Origin

Boston, Massachusetts.

Father James Harrison.

Note: student arrived with

significant emotional distress.

Previous education, home taught.

Sarah’s hands

trembled as she photographed the card.

What else do the records show? Margaret

pulled the corresponding student file, a thin folder containing intake forms and progress reports.

The intake document

dated September 10th, 1889, provided devastating details.

Student is profoundly deaf following childhood fever.

has been educated at home by father using tactile

communication method.

Father reports recent family crisis necessitating placement.

Student appears intelligent

but withdrawn.

The progress reports painted a picture of a traumatized girl slowly finding her footing.

October 1889.

Emma continues to struggle with transition.

Cries frequently.

December

1889.

Emma beginning to engage with lessons, shows particular aptitude for written

English.

March 1890.

Emma has made two friends, smiles

occasionally.

Sarah read through 5 years of reports, watching Emma Harrison grow from a

frightened 14-year-old into a young woman.

By 1892, reports noted her

excellence in academic subjects and her work helping younger deaf students.

In 1894, at age 19, Emma graduated and took

a position as an assistant teacher.

This is remarkable, Margaret said.

She

not only survived her trauma, but used her experience to help others.

The final

document was a letter written in Emma’s own hand addressed to the school’s director in 1895.

Dear Dr.

Williams, I write to inform you that my father has passed away in Providence.

He came to visit me last

month and we had a long conversation, our hands speaking the language he taught me.

He wanted me to know he never

stopped thinking of my mother, that he prayed for her peace every day, and that he hoped I would forgive him for the

choices he made to keep us safe.

I told him there was nothing to forgive.

He

gave me the photograph taken of our family in 1889, the last picture before everything changed.

When I look at it

now, I can feel his hand on my shoulder again, telling me, “Stay quiet, stay

safe, stay strong.” Your grateful student, Emma Harrison.

The Massachusetts State Archives held

records from the Boston Lunatic Hospital, though accessing them required navigating layers of privacy

restrictions.

Sarah submitted formal research requests, explaining her project’s historical significance.

Two

weeks later, she received permission to examine non-medical records.

intake documents, legal petitions, and witness

statements related to commitment proceedings.

The reading room was quiet on a Wednesday morning.

The file for

Katherine Harrison was thin, many pages having been destroyed in a fire in the 1920s.

But what remained told a

devastating story, the commitment petition filed by James Harrison on June 12th, 1889 was written in careful legal

language that couldn’t mask the desperation behind it.

My wife Catherine has suffered from episodes of violent

mania for the past 3 years, growing progressively worse.

She has attacked our children on multiple occasions.

I

fear for their safety and her own.

I have exhausted all other remedies.

Witness statements from neighbors

painted a picture of a household in crisis.

Mrs.

Helen Bradford, who lived next door, testified, “I heard shouting

and crashes several times per month.

Once I saw Mrs.

Harrison throw a plate at her daughter through the kitchen

window.

The child, the deaf one, she couldn’t hear her mother coming and didn’t know to run.

Thomas Palmer, a family friend, provided more context.

James Harrison is a good

man trying to manage an impossible situation.

His eldest daughter is deaf and cannot hear when her mother is

having one of her episodes.

More than once, I’ve seen that child with bruises she couldn’t explain because she didn’t

hear the danger approaching.

The most haunting testimony came from Dr.

Samuel Brooks, the family physician.

I have

treated Mrs.

Harrison for 3 years.

Her condition has deteriorated marketkedly.

She experiences periods of profound

depression followed by episodes of violent agitation.

She has expressed the belief that her daughter’s deafness is

divine punishment for some unspecified sin and has attempted to cure the child through violent means.

The children,

particularly young Emma, are at grave risk.

Sarah closed her eyes against tears.

Catherine Harrison hadn’t been a monster.

She’d been a woman suffering from what would now likely be diagnosed

as bipolar disorder with psychotic features.

Living in an era when mental illness was barely understood and

treatment options were limited to isolation and restraint.

The intake record from the hospital

noted Catherine’s admission on June 18th, 1889.

Patient arrived in state of extreme

agitation.

Required restraint has been separated from children per court order.

Prognosis poor.

The final record was dated March 1892.

Patient Katherine Harrison deceased.

Cause pneumonia following prolonged

confinement.

Sarah returned to Rebecca Stern’s office with all the documentation she’d

gathered.

the commitment records, Emma’s school files, the family’s scattered history.

Together, they studied the

photograph again.

Now, understanding the full context of that frozen moment.

Look

at it now, Rebecca said, knowing what was about to happen.

Every detail takes

on new meaning.

Catherine Harrison sat with rigid posture, hands clenched in

her lap.

But her eyes, which Sarah had initially read as vacant, now seemed to

be fighting for control.

This was a woman in the grip of mental illness, holding herself together

through sheer force of will for just long enough to sit for this photograph.

She knew, Sarah said softly.

She must

have known what was coming.

Possibly, Rebecca agreed.

Or perhaps this was one

of her more lucid moments.

The records mentioned she cycled between mania and depression.

This could have been taken

during a relatively stable period.

The two young boys sat close to their mother, but not touching her, a

protective distance.

Their faces showed the weariness of children who’d learned to read moods and anticipate danger.

Robert, the older boy, had his hand gripped on the arm of his mother’s chair, ready to steady it, or perhaps to

push himself away quickly if needed.

Rebecca positioned her own hand in the same configuration as James Harrison’s

again.

I’ve been studying historical tactile communication systems.

I consulted with colleagues who specialize

in 19th century deaf education.

Based on documented finger spelling systems from

that era and region, we can make an educated interpretation.

She demonstrated slowly.

The thumb

pressed down typically indicated emphasis.

The index finger extended often represented you.

The middle and

ring fingers curved this way.

In several documented family systems, this meant quiet or silence.

The pinky pressed

firmly could indicate safe or safety.

So, he’s telling her, “You stay quiet.

Stay safe.” Sarah said, “That’s my interpretation.” And the pressure of his hand, visible even in the photograph,

adds emotional weight.

He’s not just conveying information.

He’s trying to reassure her, to prepare her for what’s

coming without frightening her more than necessary.

They looked at Emma’s face again.

The tension around her eyes made sense now.

She was receiving her father’s message, understanding what it meant,

trying to stay composed for the photograph.

Her body language pressed close to her

father, spoke of trust and fear in equal measure.

Rebecca pulled out Emma’s

letter from Hartford.

Listen to how she describes it.

When I look at it now, I can feel his hand on my shoulder again,

telling me the same thing he always told me.

Stay quiet, stay safe, stay strong,

she added.

Stay strong, Sarah noted.

Yes, because that’s what the message

meant emotionally beyond the literal words.

Sarah spent the following weeks tracing what happened to the Harrison

family after that photograph was taken.

The story emerged in fragments, census records, city directories, school

enrollment documents, each piece revealing how a single family fractured and tried to survive.

James Harrison

sold the family house on Tmont Street in August 1889, 2 months after Catherine’s

commitment.

The property records showed he received far less than the house was worth.

A desperate sale by a man who

needed to relocate quickly.

He moved to Providence, Rhode Island, where he found work as a bookkeeper at a textile mill.

The two boys, Robert and Thomas, were harder to trace.

Sarah found enrollment records showing they attended a boarding

school in Worcester for a year, then seemed to disappear from Massachusetts records entirely.

She eventually

discovered them in Philadelphia census records from 1900.

Both working as clerks, living in separate boarding

houses, no mention of family.

They scattered, Rebecca said when Sarah shared her findings.

It wasn’t uncommon.

Families dealing with mental illness and institutionalization often fractured completely.

The stigma was enormous and

people wanted to escape it.

Emma’s trajectory was clearest.

After

graduating from the American School for the Deaf, she worked there as an assistant teacher for 3 years, then

moved to a similar position at a school in Pennsylvania.

The 1900 census showed her living in Philadelphia, occupation

listed as teacher of the deaf, boarding at a residential school.

Sarah found something remarkable in the school’s

newsletter from 1898.

An article written by Emma about teaching deaf children whose families

had experienced trauma.

She wrote, “These children need more than education

in language and practical skills.

They need to know that silence need not mean isolation, that what they have survived

does not define what they can become.” Through genealogical records, Sarah traced Emma’s life further.

She never

married, but she remained at the Pennsylvania school for 23 years, eventually becoming head teacher.

Former

students remembered her decades later as strict but deeply caring, someone who understood what it meant to feel

frightened and alone.

James Harrison died in Providence in 1895 at age 48.

The death certificate listed heart failure, but Sarah wondered if it wasn’t just grief and exhaustion that killed

him.

He’d fought for years to protect his children from their mother’s illness, made the agonizing decision to

have Catherine committed, then watched his family dissolve despite his best efforts.

Sarah found his obituary in the

Providence Journal.

A brief notice.

James Harrison, bookkeeper, age 48,

survived by three children.

Services private.

Catherine’s grave was in the

cemetery at the Boston Lunatic Hospital in a section reserved for indigent patients.

There was no headstone, just a

plot number in the burial register.

She’d died alone in that institution, separated from her children, her mind

ravaged by an illness no one understood how to treat.

Sarah arranged to meet

Helen Richards again, this time bringing all the documentation she’d gathered.

They met at a small cafe in Cambridge and Sarah spread photocopies of records across the table.

The commitment papers,

Emma’s school files, the census records showing the scattered family, the photograph that had started everything.

Helen examined each document carefully, her expression shifting between sadness and recognition.

It makes sense now, she said finally.

My grandmother, Emma’s daughter, she was

also a teacher of deaf children.

I never understood why she was so passionate about it, why she always said that every

child deserved to feel safe and understood.

This is why Emma had a

daughter,” Sarah asked, surprised.

“The records she’d found showed Emma never married.

She adopted a deaf girl in

1905,” Helen explained.

There’s not much documentation.

Adoption was informal

then, but family stories say Emma took in a child whose mother couldn’t care for her, raised her, educated her, gave

her the childhood Emma herself had lost.

The pattern continued through

generations.

Helen’s mother had worked with deaf children too, though by then the field

had changed dramatically.

It became a family legacy, Helen said.

Helping deaf children, especially those from difficult circumstances.

Now I understand where it started with

Emma and her father and a language only they could speak.

Sarah showed Helen the analysis Rebecca had done of the hand

position in the photograph.

Your great great-grandfather was telling Emma to stay quiet, stay safe.

He was preparing

her for what was coming.

Her mother’s removal, the family’s separation, everything that was about to change.

And she kept that photograph her entire life,” Helen said, touching the image gently.

Kept the message her father gave

her and passed it on in her own way to every frightened child she taught.

They talked for hours, filling in gaps with

family stories Helen remembered.

Her grandmother had spoken occasionally about being raised by Emma, about

learning that silence could be a form of communication as powerful as speech, that safety sometimes meant difficult

choices, that love persisted even through tragedy.

Emma never talked about her mother,

Helen said.

My grandmother said the one time she asked about Emma’s parents, Emma told her simply, “My father was a

good man who did the best he could.

My mother was sick and couldn’t help herself.

Both deserve to be remembered

with compassion.

Sarah felt tears welling again.

After

everything, the violence, the trauma, the family’s destruction, Emma had found a way to hold both truths, her mother’s

illness, and her father’s impossible choices.

The pain she’d endured, and the strength she’d found.

“What will you do

with this research?” Helen asked.

“I want to tell their story,” Sarah said.

not sensationalize it, but honor what they survived.

The photograph isn’t just a historical artifact.

It’s evidence of

how people communicated, protected each other, and endured impossible circumstances.

Helen nodded.

Emma would approve.

She always believed that understanding the past helped us do better in the present.

Three months later, Sarah completed her restoration of the photograph.

The image had been cleaned, stabilized, and

documented with all the historical context she’d uncovered.

She prepared an exhibition at the conservation lab

titled Silent Messages: Communication and Survival in Victorian Boston.

The

exhibition displayed the Harrison family photograph alongside Sarah’s research explaining tactile communication

systems, the realities of mental illness in the 19th century, and how families

like the Harrisons navigated impossible choices with limited resources and crushing stigma.

Rebecca contributed a

section on deaf education history, showing how families developed their own communication systems and how those

informal methods eventually influenced formal deaf education.

Margaret from Hartford provided Emma’s school records,

showing her transformation from traumatized child to accomplished teacher.

The exhibition opened on a cold

January evening.

Helen attended with her daughter, Emma’s great great granddaughter, a speech therapist who

worked with deaf children.

Three generations stood before that photograph, understanding now what it

truly represented.

Media coverage was modest but meaningful.

The Boston Globe

ran a feature about the exhibition, emphasizing how Sarah’s careful investigation had revealed a family’s

hidden story.

Several deaf community organizations reached out interested in the tactile

communication system James Harrison had developed with his daughter.

But the most touching response came from

visitors who saw their own family struggles reflected in the Harrison story.

People dealing with mental

illness, families making difficult choices to protect children.

Individuals who’d survived trauma and built

meaningful lives afterward.

One visitor, an elderly woman, stood before the photograph for nearly an hour.

Finally,

she approached Sarah.

“My grandfather was deaf,” she said.

My greatg

grandmother developed her own way of talking to him, touching his hands and patterns.

We thought it was just

something she’d invented, but maybe it was more common than we knew.

Maybe

there are more families like this, stories we haven’t uncovered yet.

Sarah

realized she was right.

The Harrison family photograph had survived by chance, and only because Sarah had

recognized something unusual in that hand position.

How many other photographs held similar secrets? how

many families had developed their own languages, made their own impossible choices, and left behind evidence that

no one had yet learned to read.

She thought about James Harrison standing in that studio in 1889, positioning his

hand carefully on his daughter’s shoulder, making sure the photographer captured that specific moment.

He

couldn’t have known that more than a century later, someone would finally understand what he’d been saying.

But

perhaps he’d hoped.

Perhaps that’s why he’d insisted on no retouching, on

capturing the image exactly as it was, because he wanted the truth preserved,

even if it took generations for someone to see it.

The photograph now sat in a

climate controlled case, properly preserved and contextualized.

But its real preservation was in understanding, knowing that behind that formal Victorian composition was a

father telling his deaf daughter that despite everything about to happen, she should stay quiet, stay safe, and find a

way to stay strong.

And she had.

Emma Harrison had taken that message and

built a life that honored it, helping other frightened children find their own strength, their own ways to communicate,

their own paths through trauma to survival.

The exhibition would close eventually.

The photograph would return

to Helen’s family, but the story would persist.

That was the real legacy.

Not

the image itself, but what it taught about resilience, communication, and the lengths people go to protect those they

love.

Even when every choice feels impossible, Sarah stood in the quiet gallery after everyone had left, looking

one last time at the Harrison family, frozen in that moment before everything changed.

Five people bound by blood and

circumstance, each carrying their own private pain, together for one final photograph.

And in that moment, captured

forever a father’s hand speaking a language of love and protection that had waited 135 years to be understood.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load