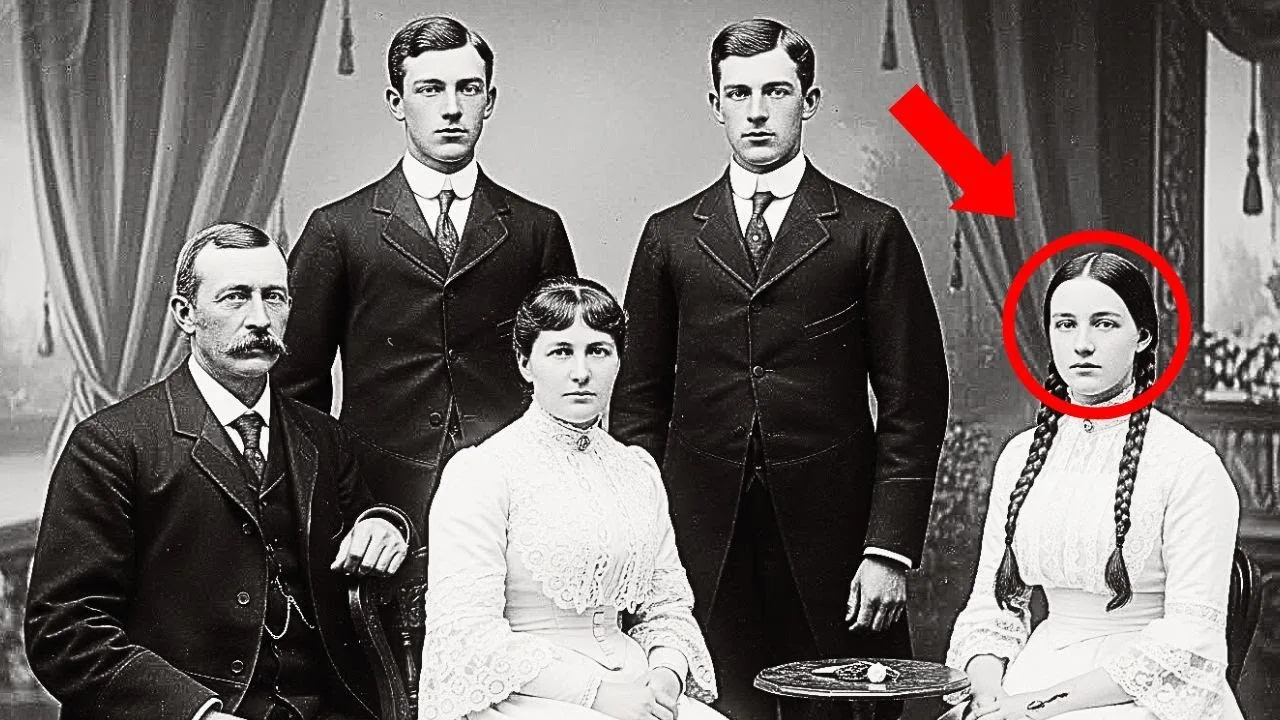

The truth behind this 1892 family portrait is more macob than anyone imagined.

The afternoon light filtered through the tall windows of the Chicago Historical Society’s archive room, casting long shadows across rows of wooden cabinets filled with forgotten stories.

Sarah Martinez wiped the dust from her hands and glanced at the clock.

Nearly 5:00 p.m.

and she still had three more boxes to catalog before the weekend.

She had been working as a curator at the society for 6 years.

And while most days blended into a comfortable routine of preservation and documentation, there were moments, rare electric moments, when something remarkable surfaced from the past.

Today felt different.

There was a heaviness in the air.

Or perhaps it was just her imagination after sorting through donation boxes for eight straight hours.

The latest acquisition had arrived that morning from the estate of a woman named Dorothy Chen, who had passed away at 93.

Her family had donated several items, clothing, books, a collection of depression era postcards, and a large gilded frame wrapped carefully in brown paper.

Sarah had saved it for last, intrigued by its weight, and the faint smell of old varnish that seeped through the wrapping.

She cut through the tape slowly, peeling back layers of paper until the portrait emerged.

It was stunning, a formal family photograph from 1892, perfectly preserved despite its age.

The clarity was remarkable for its time, capturing every detail with an almost unnerving precision.

Five people stood arranged before an ornate backdrop.

a stern-looking man in his 50s wearing a dark suit.

A woman in an elaborate dress with lace sleeves.

Two young men who appeared to be in their 20s and a girl who couldn’t have been more than 16.

Sarah placed the portrait on the examination table and switched on the overhead lamp.

The family’s clothing suggested wealth.

The quality of the fabric, the tailoring, the jewelry the woman wore.

But something about their expressions caught her attention.

The father and son smiled confidently at the camera, embodying the prosperity of Chicago’s gilded age.

The mother’s smile was more reserved, almost painted on.

But the youngest, the girl standing slightly apart from the others.

Her smile didn’t reach her eyes at all.

There was something hollow in her gaze, something that made Sarah’s breath catch in her throat.

She leaned closer, studying the girl’s face, and that’s when she noticed it.

Sarah adjusted the magnifying lamp, bringing it directly over the portrait.

Her heart beat faster as she focused on the girl’s wrists, visible just below the lace cuffs of her high collared dress.

There, barely perceptible in the sepia tones of the old photograph were marks, dark shadows that could have been dismissed as imperfections in the print or tricks of the light.

But Sarah had examined thousands of historical photographs.

She knew the difference between damage and detail.

These were bruises.

She reached for her phone and snapped several photos, then zoomed in on the screen.

The marks became clearer, circular, as if from fingers gripping too tightly.

Her stomach twisted.

For a moment, she sat back in her chair, staring at the portrait with fresh eyes.

The arrangement of the family suddenly seemed less formal and more strategic.

The girl stood slightly separated, her body angled as if trying to create distance.

The father’s hand rested on the back of her chair, but Sarah noticed now how his fingers curved inward almost possessively.

“Who were you?” Sarah whispered to the photograph.

She flipped the frame over carefully, searching for any identifying information.

A small brass plate was affixed to the back, tarnished with age, but still legible.

She grabbed a cloth and gently polished it until the engraving revealed itself.

The Harrington family, Chicago, Illinois.

October 1892.

Sarah’s eyes widened.

The Harrington name was legendary in Chicago history.

Industrial magnates who had made their fortune in steel and railroads during the city’s rapid expansion in the late 19th century.

Their legacy was everywhere.

Harrington Hall at the University of Chicago, Harrington Memorial Hospital, even Harrington Street downtown.

The family had been philanthropists, civic leaders, pillars of society.

But looking at this portrait, at the haunted expression of the youngest member, Sarah wondered what had been hidden beneath that gleaming reputation.

She grabbed her laptop and began searching the historical society’s database.

There had to be more information about this family.

Records, newspaper clippings, anything that might explain what she was seeing in this photograph.

The search returned dozens of results.

Articles about business deals, society events, charitable donations.

But as Sarah scrolled through them, she noticed something odd.

In every article after 1893, the family was listed as four members, not five.

The girl had vanished from the record.

Sarah stayed at the archive until nearly midnight, unable to pull herself away from the mystery unfolding on her computer screen.

She had cross-referenced census records, society pages, and business journals, building a timeline of the Harrington family’s public life.

What she discovered was both impressive and unsettling.

Charles Harrington, the patriarch, had arrived in Chicago in 1871, just months after the Great Fire had devastated the city.

He had seized the opportunity that disaster presented, investing in steel production and railroad infrastructure as Chicago rebuilt itself into an industrial powerhouse.

By 1880, he owned three factories on the south side, employing hundreds of workers, many of them immigrants from Eastern Europe and Ireland.

His wife Victoria came from old Boston money.

Their marriage in 1873 had been celebrated in newspapers across the country as a union of new wealth and established society.

They had three children, Robert born in 1874, James born in 1876, and Elellaner born in 1877.

Ellaner, finally a name for the girl in the portrait.

Sarah pulled up everything she could find about her.

Elellaner appeared in society columns throughout the 1880s, attending parties, participating in charity events, always described as lovely or accomplished.

But in January 1893, just 3 months after the portrait was taken, her name disappeared completely.

No marriage announcement, no obituary, nothing.

It was as if she had simply ceased to exist.

Sarah rubbed her tired eyes and leaned back in her chair.

The silence of the archive felt oppressive now, broken only by the hum of the overhead lights.

She looked again at the portrait, at Eleanor’s face, and felt a surge of determination.

This girl had been erased from history, but Sarah was going to find out why.

The next morning, Sarah arrived at the historical society with renewed purpose.

She had barely slept, her mind racing with questions and theories.

Her colleague, Marcus, raised his eyebrows when he saw her already at her desk at 7:30 a.m.

Someone’s eager today, he said, setting down two cups of coffee.

“What’s got you so wired?” Sarah gestured to the portrait now displayed on her monitor alongside several document scans.

“Look at this family, the Harringtons, major industrialists from the 1890s.

But their youngest daughter just vanishes from all records in 1893.

No explanation, no trace.

Marcus leaned in, studying the image.

Maybe she died.

Diseases were pretty common back then.

That’s what I thought initially, but there’s no death certificate, no obituary, no burial record, nothing.

Marcus pulled up a chair.

His curiosity clearly peaked.

“That is strange.

Rich families like that would have had elaborate funerals.

Society pages would have covered it extensively.” Exactly, Sarah said, pulling up another document on her screen.

And look at this.

I found a reference in a workers union newsletter from 1892.

It mentions Miss E.

Harrington visiting one of her father’s factories in September, just a month before this portrait was taken.

The writer seemed surprised that a woman from such a wealthy family would show interest in the working conditions.

She clicked to another scan, a brief mention in the Chicago Tribune Society section from October 1892.

Miss Eleanor Harrington was notably absent from the Witman Charity Gala last evening with the family citing a brief illness.

“Brief illness?” Marcus repeated.

“Right around the time this photo was taken.” Sarah nodded, zooming in on Eleanor’s face in the portrait again.

“Look at her expression, Marcus.

This isn’t someone who’s physically ill.

This is someone who’s terrified.” Marcus studied the image more carefully, then noticed the marks on Eleanor’s wrists that Sarah had highlighted.

His expression darkened.

Are those what I think they are? Bruises? Recent ones based on their darkness in the photograph.

They sat in silence for a moment, the weight of the discovery settling between them.

Finally, Marcus spoke.

So, what’s your theory? You think the family was abusing her? I think something happened in that household that they wanted to keep quiet.

Sarah said something that led to Elellanar being completely removed from the historical record and I think it might have had something to do with those factory visits.

Marcus leaned back processing.

You know the Harrington family still has descendants in Chicago, right? The great grandson William sits on the board of about half the major institutions in the city.

Sarah felt a chill.

That could complicate things.

That’s putting it mildly.

If you start digging into family secrets from 130 years ago, and it reflects badly on their legacy, you’re going to make some powerful enemies.

Sarah looked at the portrait again at Elellanar’s hollow eyes and the bruises on her wrists.

She deserves to have her story told, Marcus.

Whatever happened to her, she shouldn’t just be erased.

He nodded slowly.

Then you’ll need to be thorough.

Document everything.

Verify every source.

If you’re going to challenge the legacy of one of Chicago’s most prominent families, you’ll need irrefutable evidence.

Where would you start? Sarah asked.

Marcus thought for a moment.

Factory records.

If Elellanar was visiting the factories, there might be documentation, inspection reports, correspondence, witness accounts.

The historical society has an industrial archive in the basement.

It’s a mess, but it might have what you need.

The basement archive was exactly as Marcus had described, a labyrinth of filing cabinets, storage boxes, and forgotten documents stacked half-hazardly on metal shelves.

The air was thick with the smell of old paper and mildew.

Sarah spent the entire afternoon searching through boxes labeled industrial Chicago, 1880, 1900.

Her hands growing increasingly dirty with dust and grime.

Most of the documents were routine production reports, shipping manifests, inventory lists.

But then in a box marked labor relations, miscellaneous, she found something that made her pulse quicken.

It was a thin folder labeled Harrington Steelworks complaints and incidents 1891 to 1893.

Inside were dozens of handwritten reports, most of them describing workplace accidents, crushed fingers, burns from molten metal.

one worker who had lost an arm when a machine malfunctioned.

The reports were clinical, almost callous in their brevity.

Each one ended with the same notation.

No compensation awarded, worker dismissed.

But halfway through the stack, Sarah found something different.

It was a letter written in elegant script on expensive paper dated November 1892, just 1 month after the portrait had been taken.

The letter was addressed to Charles Harrington and it was signed by someone named Thomas O’Brien who identified himself as a representative of the Workers Protection League.

Sarah read it carefully.

Mr.

Harrington, I write to you once more regarding the deplorable conditions in your Southside facility.

Despite your assurances that improvements would be made, my colleagues report that nothing has changed.

Workers continue to labor 14-hour shifts in dangerous conditions with inadequate ventilation and no safety protocols.

Three men have died in your factories this year alone.

I understand that your daughter, Miss Elellanar, toured the facility in September and was reportedly disturbed by what she witnessed.

Perhaps she could convince you where others have failed.

These workers deserve basic human dignity.

Sarah’s hands trembled as she held the letter.

Elellanar had seen the truth about her father’s business.

She had witnessed the suffering of the workers firsthand, and something about that experience had deeply affected her.

She photographed the letter and continued searching.

Near the bottom of the box, she found another document, a transcript of testimony given to a city inspector in December 1892 by a factory foreman named Patrick Murphy.

His words were damning.

The girl came through in September, Miss Harrington.

She wasn’t supposed to be there.

Her father was furious when he found out.

She walked through the whole place talking to the men, asking questions about hours and wages.

She saw young Tommy Kuzlowski right after he burned his hand on the furnace.

No one had bandaged it.

She started crying, demanded to know why there was no doctor.

Mr.

Harrington dragged her out of there himself.

We could hear him shouting at her in his office.

Sarah emerged from the basement archive as the evening sun cast long shadows through the building.

Her mind raced with the pieces she was assembling.

Elellaner hadn’t just noticed the poor conditions in her father’s factories.

She had actively tried to intervene to help the workers who were suffering.

And her father had been enraged.

She spread out photocopies of the documents on her desk, arranging them chronologically.

The timeline was becoming clearer.

Eleanor visited the factory in September 1892.

workers remembered her compassion, her horror at what she witnessed.

In October, the family portrait was taken.

Ellaner bearing bruises, looking hollowed out.

In November, the workers advocate referenced Elellanar’s visit in his letter to Charles Harrington.

And by January 1893, Eleanor had vanished from all public records.

Sarah’s phone buzzed.

It was Marcus still at work.

I found something you need to see.

Coming up.

Minutes later, Marcus appeared carrying a leatherbound ledger.

This was in the uncataloged donation section.

It came in with a batch of items from an old church on the south side that closed down last year.

Look at the date.

He opened the ledger to a page marked with a slip of paper.

It was a registry from St.

Adelbert’s Church recording charitable donations and visitors.

Sarah scanned down the page until she saw it, an entry from December 1892.

Miss Elellanar Harrington visited today, accompanied by her lady’s maid.

She inquired about our programs for factory workers families and donated $200 from her personal account.

She seemed distressed and asked to speak with Father Kowalsski privately.

She expressed concern for those who suffer while others prosper and asked about the possibility of sanctuary.

sanctuary.

Sarah breathed.

She was looking for a way out.

Marcus nodded grimly.

There’s more.

I checked the next few pages.

Eleanor returned to the church twice more in December, always without her family’s knowledge.

The last entry is from December 28th.

After that, nothing.

Sarah felt her throat tighten.

She was planning something.

Maybe she was going to expose her father or run away or or she was stopped.

Marcus finished quietly.

The weight of what they were uncovering settled heavily in the room.

This wasn’t just a historical curiosity anymore.

This was evidence of a young woman who had tried to stand up for what was right, who had seen injustice and refused to look away, and who had paid a terrible price for it.

“I need to find out what happened to her,” Sarah said.

There has to be more documentation somewhere.

Letters, diaries, something.

The following morning, Sarah contacted the Newberry Library, which housed extensive collections of Chicago family papers.

After explaining her research, the archivist mentioned that they had recently acquired a collection of letters and documents from the estate of a woman named Katherine Walsh, who had worked as a domestic servant for wealthy Chicago families in the 1890s.

The collection hasn’t been fully cataloged yet, the archavist explained over the phone.

But I remember seeing the Harrington name mentioned in some of the materials.

You’re welcome to come examine them.

Sarah arrived at the Newberry within the hour.

The archivist, a woman named Dr.

Patricia Reynolds, led her to a research room where several boxes of Katherine Walsh’s papers were laid out on a table.

Catherine was a ladies maid, Dr.

Reynolds explained.

She worked for several prominent families throughout her career and kept meticulous records, letters she received, diary entries, even some items that were given to her.

She passed away in 1947 at the age of 83.

Sarah began carefully going through the papers.

Most were routine correspondence with family members, records of wages received, recommendations from employers.

But in the third box, she found a small bundle of letters tied with a faded blue ribbon.

Her heart nearly stopped when she saw the signature on the first letter, Eleanor Harrington.

The letters were addressed to Catherine Walsh, dated between October and December 1892.

Sarah’s hands shook as she carefully untied the ribbon and began to read.

The first letter, dated October 15th, 1892, was written in elegant but hurried script.

Dear Catherine, thank you for your kindness during yesterday’s ordeal.

I know father was furious with you for accompanying me to the factory, but I am grateful beyond words that you did not abandon me.

What I saw there haunts my every waking moment.

Those men working in such heat, such danger, for wages that barely feed their families.

Children, Catherine, some of them no older than 12, covered in soot and burns.

And my father profits from their suffering while we live in luxury.

I cannot bear it.

I must find a way to help them, but I do not yet know how.

Father has forbidden me from speaking of it, but silence feels like complicity.

Please burn this letter after reading it.

I trust no one else.

Yours in friendship, Elellanar.

Sarah felt tears prick her eyes as she read.

Elellanar’s words were raw with compassion and moral anguish.

She continued to the next letter, dated November 3rd.

Catherine.

Father discovered my journal where I had been documenting what I learned about the factory conditions.

There was a terrible confrontation.

He called me ungrateful, hysterical, dangerous to the family’s reputation.

He has confined me to my room and forbidden me from leaving the house.

Mother says nothing.

She never does.

My brothers look at me as if I have lost my mind.

But I have not lost my mind, Catherine.

I have found my conscience.

I am attempting to make contact with the workers protection league.

They must know the truth about father’s factories.

If I can provide them with evidence, production records, wage documents, safety reports, perhaps they can force changes.

But I must be careful.

Father is watching me constantly now.

Sarah continued reading through Elellaner’s letters, each one more desperate than the last.

The final letter dated December 30th, 1892 sent a chill down her spine.

Catherine, I fear this will be my last letter to you.

Father has made arrangements for me to be sent away.

He discovered that I have been meeting with Father Kowalsski and that I passed documents to Mr.

O’Brien of the Workers Protection League.

Tomorrow I am to be taken to a private sanitarium in rural Wisconsin.

Father tells everyone I have suffered a nervous breakdown that the pressures of society have been too much for my delicate constitution.

But you and I know the truth.

I am being silenced.

I am being erased.

The doctors at this place, father assures me, are discreet and understand that difficult daughters sometimes require long-term care and isolation.

I do not know if I will ever return to Chicago.

Please, Catherine, if anything happens to me, remember that I was not mad.

I was not hysterical.

I simply could not ignore the suffering I witnessed.

Keep these letters safe.

Perhaps someday someone will want to know the truth.

With love and gratitude, Elellanor Sarah sat back, her vision blurring with tears.

Eleanor hadn’t died in 1893.

She had been institutionalized by her own father to protect the family’s reputation and business interests.

Sent away and forgotten, erased from the record as if she had never existed.

Dr.

Reynolds had been watching Sarah’s reaction with concern.

Are you all right? Sarah wiped her eyes and nodded.

I’m all right.

But Elellanar Harrington wasn’t.

She was committed to an asylum for trying to expose the truth about her father’s factories.

That was unfortunately common, Dr.

Reynolds said quietly.

Women who challenged their families or society’s expectations were often diagnosed with hysteria or nervous disorders and institutionalized.

It was a convenient way to silence them.

Is there any way to find out what happened to her after this? Sarah asked.

If she was sent to Wisconsin, there must be records.

Doctor Reynolds thought for a moment.

Asylum records from that era are difficult to access.

Many institutions have closed and records were often destroyed or lost.

But if you know the approximate location and time frame, you might be able to track something down through state archives.

Sarah spent the rest of the day at the library documenting Eleanor’s letters and searching for any additional clues about which sanitarium she might have been sent to.

In Catherine Walsh’s diary entries from early 1893, she found one brief mention.

received word that Miss Eleanor has been taken to Lakeshore Retreat near Madison.

Mrs.

Harrington came to the house today and gave me three months wages, telling me my services were no longer needed.

I believe she fears I know too much.

Lakeshore Retreat.

Sarah had a location.

2 weeks later, Sarah found herself driving through the Wisconsin countryside, following directions to the site where Lakeshore Retreat had once stood.

The facility had closed in 1957, but the state historical society had preserved some of its records, which Sarah had spent days petitioning to access.

The building itself was long gone, replaced by a small community park, but the Wisconsin Historical Society archives in Madison held several boxes of patient records from the sanitarium’s early years.

With the help of an archivist named Tom, Sarah located Ellaner’s file.

It was heartbreaking.

Elellanar had been admitted on January 4th, 1893 with a diagnosis of moral insanity and hysteria.

Her father had signed all the paperwork, claiming she had become delusional and dangerous to herself.

The attending physicians notes described her as agitated and insistent upon making wild accusations against her family.

But as Sarah read through the monthly reports, a different picture emerged.

Elellanar had been a model patient, quiet, cooperative, spending her days reading and writing.

The doctors noted that she showed no signs of actual mental illness, but her father continued to pay for her care and insisted she remain institutionalized until such time as she renounces her dangerous ideas and agrees to behave appropriately.

Month after month, year after year, the reports continued.

Elellanar aged in that place, her youth slipping away.

The doctors eventually recommended her release, noting that she posed no danger and showed no signs of mental instability, but Charles Harrington refused every request.

Then, in March 1914, 21 years after her admission, Sarah found a death certificate.

Elellanar had died of pneumonia at the age of 37, still a patient at Lakeshore Retreat.

She had spent more than two decades locked away, forgotten by everyone except the staff who cared for her.

Sarah sat in the archive reading room, tears streaming down her face as she read the final entry in Eleanor’s file.

It was a note from a nurse named Helen Brick, written the day after Eleanor’s death.

Eleanor Harrington passed peacefully last night.

In all my years working here, I never met a kinder or more intelligent patient.

She spoke often of the factory workers she had tried to help in her youth and said she held no bitterness toward her family, only sadness that they could not see what she had seen.

She asked that we remember her not as a patient, but as someone who tried to do what was right.

We will miss her gentle spirit.

Sarah photographed every document in Elellanar’s file, her hands steady despite her emotions.

This was the evidence she needed, proof that Elellanar had been silenced, imprisoned, and ultimately forgotten for the crime of having a conscience.

3 months later, Sarah stood before a packed auditorium at the Chicago Historical Society, preparing to present her findings.

The research had taken over her life, but she had documented everything meticulously.

the portrait with its telling details, the factory records, Ellaner’s letters, the asylum files, testimony from workers descendants, and documentation of the Harrington family’s systematic efforts to erase their daughter from history.

The presentation was titled The Silence Daughter: Elellanar Harrington and the Cost of Conscience in Gilded Age Chicago.

As Sarah began speaking, displaying the 1892 portrait on the screen behind her, she noticed several people in the audience taking notes intensely.

Journalists, she realized Marcus had quietly alerted the press to the presentation.

This photograph was taken in October 1892.

Sarah began her voice steady.

It shows the Harrington family, wealthy industrialists who made their fortune during Chicago’s rapid expansion.

But look closer at the youngest member, 16-year-old Eleanor.

Her expression tells a story that her family tried desperately to erase.

Sarah walked the audience through Elellanar’s journey, her visits to her father’s factories, her horror at the working conditions, her attempts to help, and her father’s brutal response.

She shared Eleanor’s letters, her desperation, and finally her fate.

locked away for 21 years until her death.

All because she refused to ignore human suffering.

Eleanor Harrington spent two decades in an asylum, not because she was ill, but because she threatened her family’s reputation and profits.

Sarah said she saw injustice and spoke up.

For that, she was silenced, erased, and ultimately forgotten.

But through these documents, her voice can finally be heard again.

The room was completely silent when Sarah finished.

Then someone began to clap and soon the entire auditorium was applauding.

Several people were crying.

After the presentation, a woman in her 70s approached Sarah.

“My great greatgrandfather worked in Harrington Steel Factory,” she said quietly.

“He lost two fingers in an accident there in 1891.

The family always said someone from the Harrington family had tried to help the workers, but they thought it was just a story.

Thank you for proving it was true.

Over the following weeks, Sarah’s research sparked a broader conversation about labor history, women’s rights, and the way inconvenient truths are buried by those with power and money.

The Harrington family declined to comment publicly, but quietly their current foundation established a scholarship in Ellaner’s name for students studying labor rights and social justice.

Sarah returned to the archive room where she had first discovered the portrait.

It now hung on the wall of a new exhibit dedicated to Eleanor’s story.

Visitors came daily to see the photograph and learn about the young woman who had refused to look away from suffering.

Standing before the portrait, Sarah noticed something she hadn’t seen before.

In the reflection of the glass frame behind the family, barely visible, was another figure, likely the photographer.

But Sarah chose to see it differently.

Another witness to what had happened in that room.

Someone else who had seen Eleanor’s pain and said nothing.

“But we’re not saying nothing now,” Sarah whispered to the portrait.

“Your story is being told, Eleanor.” “Finally.

The girl in the photograph seemed to look back at her, no longer hollow, but somehow at peace, as if she had been waiting all these years for someone to finally see the truth, and refused to let it remain hidden.

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load