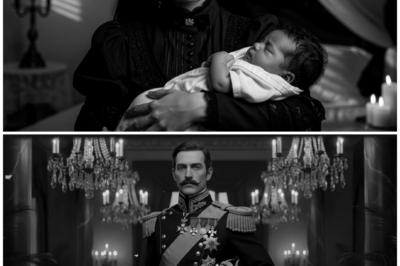

The Slave Forced to Sleep with the Master’s Wife — And What He Observed Every Night (1847)

In Cuba in 1847, where sugar was white gold and human beings were tools of production, one powerful man received a verdict that shattered everything he believed he’d built.

His body could not continue his name.

The solution offered was so brutal it would change three lives forever—and light a fuse that would take two decades to explode.

Havana, April 1847.

The city smelled of cured tobacco and salt.

Sun burned the colonial stone.

Mule carriages rattled between vendors shouting prices for mangos and bananas.

Don Vicente Armando Salazar stepped from his coach at No.

47 Obispo Street, a three-story building with iron balconies.

Dr.

Sebastián Morales—physician to the island’s most prominent families—waited upstairs.

Vicente was fifty-two, but looked older.

His back bent by decades walking cane rows in sun that crushed men’s will.

His face was leather, his hands dyed dark by sugar juice.

He owned San Cristóbal—eight hundred hectares of fertile Matanzas land—and one hundred forty-three people who worked it from dawn until darkness.

Dr.

Morales, sixty, educated at Salamanca, ushered him into a cedar-paneled office where Paris and London instruments glinted in glass cases.

“Please sit, Don Vicente.” He adjusted gold spectacles, examined folders thick with notes—samples analyzed, microscopic observations, a Madrid consultant’s opinion.

“The results are conclusive,” Morales began.

“Your issue is not mechanical, but essential.”

“Speak plainly,” Vicente said, fists clenched.

“Your seed lacks vigor,” the doctor said softly.

“Structures responsible for procreation are present but inactive.

We see this in roughly one of twenty men.

It may be congenital or age-related.

Given twenty-eight years of marriage without conception, this appears to be congenital.”

Silence.

Only the pendulum clock’s tick.

“You are saying I will never—”

“I’m afraid so.

Your wife, Doña Leonor, was examined by a colleague specializing in female conditions.

She is entirely capable of conceiving.

The problem lies solely with you.”

Twenty-eight years.

Twenty-eight years believing Leonor could not give him children.

Twenty-eight years of doctors, folk healers from fields, pilgrimages to churches, vows to saints.

All useless, because the defect was his.

“Is there a remedy?” Vicente asked, voice breaking.

Morales drew a parchment from his desk.

“There is a practice—unofficial, rarely discussed, known among certain old families who face this situation.”

“Go on.”

“I call it biological procuration.

The practice is ancient—biblical.

When a man cannot provide heirs and his wife is fertile, another man is designated to fulfill that function under strict supervision and control.

The child born legally bears the husband’s surname; no official document reflects biological paternity.”

Blood rushed to Vicente’s head.

“You are suggesting another man…with my wife.”

“With your wife,” Morales said evenly.

“Under your supervision.

Under your roof.

It is not adultery if the husband orders it and is present as witness.

At least, that is what consulted theologians argue.

I have here the name of a Jesuit in Havana, Father Ignacio Ruiz, who has advised three families in similar circumstances.”

“And the man?” Vicente asked.

“At your discretion.

Some families pay foreign transients generously for silence and immediate departure.

Others—given their position—find the solution within their own estate, among those already under absolute control.”

The implication was crystalline.

“A slave,” Vicente whispered.

“A man of your property,” Morales corrected.

“A mouth you control, a life you control, a future you control.

It is the safest, most discreet, most practical option.

Choose one with appropriate constitution and acceptable appearance.

Proceed under your direct oversight to avoid emotional complications.”

Vicente left in a trance.

Havana felt unreal, sounds muffled like underwater.

He ordered his coach back to San Cristóbal without stopping.

Six hours across dirt roads cutting through endless cane.

At dusk, San Cristóbal rose—white columns, red tile roof, flamboyants and jacarandas bright.

Beyond: barracks for workers, sugar warehouses, the mill.

Everything was Vicente’s—except the one thing that mattered: an heir.

Leonor waited in the main salon.

Forty-five, her hair still dark with threads of silver; green eyes holding light after decades of tropical sun and monthly disappointments.

Cream silk dress—elegant in heat.

“What did the doctor say?” she asked without preamble.

Vicente poured aged rum.

He handed her one glass and emptied his own with a single swallow.

“The problem is me,” he said.

“Always has been.

I can never give you a child.”

Leonor received the blow with a calm that surprised him—perhaps twenty-eight years had exhausted tears.

“Then what do we do?” she asked.

“Our land will pass to my cousins when we die.

Everything we built will be lost.”

Vicente explained biological procuration, Father Ruiz, the brutal solution that existed.

Leonor dropped her glass.

Crystal shattered on marble; rum spread like blood.

“You want me with another man while you—”

“It is the only way,” Vicente said, avoiding her gaze.

“The only way San Cristóbal has an heir of your blood—of mine through you.

The child will be legally mine, legally ours.

No one will know the truth except us—and the man I choose.

And he will never speak.”

Leonor understood immediately.

“A slave,” she murmured.

“A man of our property,” Vicente corrected.

“A man with no voice—who will do as ordered—and be silent as ordered.”

Leonor walked to the window.

Night fell quickly in the tropics.

Barrack lamps flicked on—small points of gold in dark.

“I can’t,” she whispered.

“I can’t do that.”

“Then San Cristóbal dies with you,” Vicente said, voice hard.

“Everything your father built—everything I’ve held for thirty years—gone.

Your cousins will sell the land; they’ll scatter the people; they’ll turn this into nothing.

Is that what you want?”

Leonor stayed silent a long time.

“I need to speak to a priest,” she said.

“I have his name.”

Three days later, Father Ignacio Ruiz arrived—Jesuit in his fifties, old-school, Rome-educated, known for solving delicate problems for powerful families.

Black cassock immaculate despite heat—leather valise of documents and theological texts.

The meeting was in Vicente’s study.

Doors shut, heavy curtains drawn.

Ruiz listened without interrupting, taking occasional notes in a small notebook.

When Vicente finished, the Jesuit folded his hands.

“What you propose is not without precedent,” he began.

“In the Old Testament, Abraham and Hagar: when Sarah could not conceive, Abraham had a child with her servant under Sarah’s authorization.

Later, similar situations with Jacob, Rachel, and Bilhah.”

“So the Church permits it?” Leonor asked, barely audible.

“The Church,” Ruiz said carefully, “recognizes extraordinary situations requiring extraordinary measures.

Marriage has several purposes; one fundamental purpose is the procreation of legitimate heirs.

When natural causes impede this purpose and all medical options are exhausted, certain theologians argue that exceptional measures can be tolerated under specific conditions.”

“What conditions?” Vicente asked.

“First: the husband must be present throughout as witness that there is no affection—only fulfillment of biological function.

Second: the chosen man must be someone who cannot claim paternity—someone with no legal rights.

Third: the child must be registered immediately as legitimate issue of the marriage—no document suggesting otherwise.

Fourth: absolute secrecy—with individual confession afterwards to cleanse residual guilt.

Fifth: once the purpose is achieved, the man must be removed from the estate—sold far away—to eliminate future temptation or emotional complication.”

Vicente nodded slowly.

“All that can be arranged.

I have contacts in Jamaica and Santo Domingo.

I can sell a slave without raising suspicion.”

Father Ruiz looked at Leonor.

“Doña Leonor, you understand this requires your absolute consent.

No coercion.

It must be your free decision.”

Leonor stared at her hands.

“If it is the only way to fulfill my duty—my duty to my husband, my family, this land—then I consent.

May God forgive me.

But I consent.”

Ruiz made the sign of the cross.

“Then we proceed.

I will come weekly to ensure everything stays within acceptable bounds.

When the child is born, I will baptize him personally, guaranteeing no irregularity stains ecclesiastical records.”

Vicente did not sleep that night.

He walked through gardens until dawn, thinking of the task ahead.

He must choose a man.

Which? What criteria?

Over three days, he watched every man on his property with new eyes—cutting cane, hauling sacks, building fences—and asked himself: which of them will be the biological father of my heir?

Not someone too dark—the child must pass as theirs.

Not old or too young—productive age, vigorous.

Most important: someone who understood complex orders—some education.

That’s when he saw Mateo.

Mateo was twenty-six—about five foot eleven—strong but not overly muscular—skin lighter than others—not by chance, but because his biological father was a Spanish overseer who had spent three years at San Cristóbal before dying of yellow fever.

Mateo’s mother, Catalina, worked in the house; the overseer favored her.

The result was Mateo.

Vicente had always known the overseer’s paternity; it never mattered.

Bastards were bastards—with or without Spanish blood.

Mateo grew in barracks like everyone, worked from eight—first minor tasks—then field.

He had something different—intelligence he couldn’t hide.

At eighteen, he learned to read—no one knew how—perhaps a worker had taught him, perhaps he stole books from the great house library—but he could read, which made him dangerous—or useful.

Vicente summoned him one May afternoon.

Mateo arrived still dirty from day’s work—hands stained with dark earth, sweat shining on his face—rough pants, sleeveless shirt revealing arms scored by constant labor.

“Sir,” Mateo said—neutral voice—eyes not fully lowered like the others.

Vicente had noticed this before—Mateo had never learned total submission posture.

“Sit,” Vicente ordered, gesturing to a chair across the desk.

Mateo hesitated—slaves did not sit in their master’s presence.

Vicente’s impatient gesture insisted.

“I have a special task for you,” Vicente said.

“A task I cannot trust to anyone else.

It requires absolute discretion.”

Mateo waited.

“My wife needs to conceive a child,” Vicente said bluntly.

“I cannot provide it.

You will do it in my stead, under my supervision, in my presence, until she is pregnant.

Then you will be compensated and transferred to another property.

This is an order, not a request.

Do you understand?”

Mateo’s face didn’t show emotion; Vicente saw something change in his eyes—a spark of immediate comprehension of the humiliation Vicente chose for himself—and the power Vicente had unwittingly opened.

“I understand, sir,” Mateo finally said.

“You begin tonight.

You will come to the great house after dark.

Enter through the side door.

You will be taken to the marital room and fulfill your duty.

I will be present throughout to ensure no misunderstanding.

Any questions?”

“None, sir.”

“Good.

Present yourself at nine.

Bathe; wear clean clothes.

This must be done with some dignity.”

As Mateo turned to leave, Vicente stopped him.

“If you speak of this to anyone—any person—you will be sold to copper mines in Jamaica where life expectancy is eighteen months.

Understood?”

“Understood, sir.”

Back in the barracks, Mateo lay on his cot staring at the palm ceiling.

His mind moved fast—processing what happened.

Twenty-six years property of Vicente Salazar—twenty-six years following orders.

This was different.

It gave him something he’d never had: direct access to his oppressors’ intimacy, access to their weaknesses, access to information that might someday become power.

Night arrived wrapped in dense silence.

Nine bell strokes echoed like death sentences.

Mateo walked from barracks to the side door of the great house where the trusted older maid waited with an oil lamp.

“Follow me,” she murmured.

They climbed the servants’ back stairs—wood steps creaking.

The second floor hallway was lit narrowly by candles—shadows dancing on floral French paper.

The maid stopped before a mahogany door with bronze handles—three soft knocks like a code.

“Enter,” Vicente’s voice called.

The marital room was large—nearly a barracks in size—walls painted pale blue—lace curtains over windows—an enormous wardrobe—but what dominated was the bed: massive carved mahogany with white canopy—linen sheets likely costing more than everything Mateo had touched in life.

Leonor sat at the bed’s edge—white cotton nightdress—hair loose.

Pale face—hands trembling in her lap.

Vicente sat in a high-backed chair in the corner—trousers, white shirt, vest—as if expecting dinner guests.

He held a short leather whip—not threateningly—just holding it—a physical reminder of control.

“Close the door,” Vicente ordered.

Mateo obeyed.

“Approach the bed.”

Mateo walked slowly—boots tapping polished wood.

“Leonor,” Vicente said without emotion.

“This is Mateo.

He will fulfill the purpose we discussed.

You will lie down and allow what is necessary—without resistance—without complaint.

Mateo—you will do as required without speaking—without meeting her eyes more than necessary—without affection.

It is mechanical—biological—nothing more.

I will observe to ensure conditions are met.

Do you both understand?”

“Yes,” Leonor whispered.

“Yes, sir,” Mateo replied.

“Proceed.”

What happened in the next hour was one of the strangest, most disturbing experiences any of the three had lived.

There was no passion—no desire—only three people performing roles in a grotesque play written by desperation and social obsession.

Leonor lay on white sheets—eyes closed—breathing controlled—like a medical procedure.

Mateo approached—aware of every movement—aware of Vicente’s eyes tracking details from his corner chair—the bed’s creak—the tobacco on Vicente—the jasmine on Leonor—uneven breaths—all blending into a symphony of absolute discomfort.

Vicente did not look away.

He watched—catalogued—suffered in a way he did not fully comprehend—something in this self-imposed humiliation tore him—and fascinated him—as if watching the collapse of everything he believed himself to be—and being unable to look away.

When it ended, Mateo separated, dressed in silence, awaited instruction.

“You may withdraw,” Vicente said, voice hoarse.

“Return tomorrow at the same hour—and continue every night until the doctor confirms my wife is pregnant.”

Mateo nodded and left.

Leonor remained—eyes closed—silent tears sliding down her cheeks—staining linen.

Vicente sat in his chair—whip still in hand—staring into empty space—wondering what he had allowed to begin.

Nightly visits became routine.

Nine o’clock for eight weeks—Mateo walked from barracks to the side door—climbed the back stairs—entered the marital room—and fulfilled his function while Vicente watched.

Yet something shifted—subtle—acknowledged by none of them.

After the third week, Leonor stopped closing her eyes.

She began to look at Mateo—to study his face—his movements.

Mateo began to hold her gaze—a silent communication beyond words.

Vicente noticed.

He saw Leonor’s shoulders relax when Mateo entered.

He saw her breath change—not like a patient enduring a procedure—but like someone anticipating.

And most disturbing—he realized that he awaited those nine bells—that something sick in him needed to witness this scene again and again—that humiliation had become an addiction he could not name—nor control.

In week seven, Vicente heard something he had never heard—afterward—once Mateo dressed—Leonor whispered one word.

“Thank you.”

Two syllables—loaded with meaning—that shattered something fundamental in Vicente.

“Do not speak,” Vicente growled from his corner.

“This is not conversation.

This is function.”

But Leonor had broken protocol.

She had recognized Mateo as more than a tool.

And Mateo had nodded slightly.

At eight weeks, Dr.

Morales traveled from Havana to examine Leonor.

After an hour in the ground-floor room used as infirmary, he exited with a professional smile.

“Congratulations, Don Vicente.

Your wife is pregnant—about six weeks.

If all goes well, you will have an heir in seven months.”

Vicente felt relief—and terror.

He had what he wanted.

But the price.

“Do we continue the visits?” he asked.

Morales thought a moment.

“There is a school that suggests continuing during the first trimester helps fix the pregnancy—strengthen it.

Controversial—but some families do it as precaution.

Given the importance—I recommend continuing until three months complete.”

“Then we continue,” Vicente said—jaw tight.

Six more weeks—six more nights—six more repetitions—not as before—something had undeniably changed.

In those last weeks something had bloomed between Leonor and Mateo—something forbidden by every law—human and divine—but living anyway.

Leonor began to touch Mateo’s face after—fingers tracing his jawline.

Mateo began to linger seconds beyond necessity—looking at her with intensity beyond orders.

Vicente squeezed the whip until his knuckles whitened—but did not intervene.

To intervene would be to admit loss of control—that what began as biological transaction had become something he never anticipated.

At three months, Vicente announced the visits were over.

That last night felt different—tension heavy.

Leonor cried as Mateo dressed—tears she couldn’t stop.

Mateo looked at her with genuine pain—something Vicente had never seen on any slave’s face.

“Enough,” Vicente said, standing.

“Mateo—return to the barracks.

You will not enter this house again.”

Mateo nodded—walked to the door—and turned.

“Señora,” he said.

Two words—softened in a way that made Vicente feel pure fury.

“Out,” Vicente shouted.

“Now.”

When Mateo left, Vicente approached the bed—Leonor still crying.

“This is finished,” he said.

“That man no longer exists to you.

You will not speak his name; you will not look at him.

The child growing in your womb is my child—our child—legally—morally—in every way that matters.

Do you understand?”

Leonor nodded—not looking at him.

“Answer me.”

“Yes,” she whispered.

“I understand.”

The months that followed were taut.

Leonor spent days in silence—embroidering baby clothes, reading in the garden—avoiding Vicente except at meals.

Her belly grew—a visible success—and a constant reminder of how it was achieved.

Vicente watched her constantly—searching for signs—of what, he wasn’t sure—hidden letters—furtive looks toward barracks—whispers with maids.

Mateo had been assigned to the farthest fields—before dawn until after dusk.

Vicente ensured he had no legitimate reason to approach the great house.

Yet sometimes—when Vicente looked from his study window—he saw Mateo in the distance—pause in his work—look toward the house.

And Vicente knew exactly which window he sought.

In the fifth month, Vicente noticed something that filled him with unease.

Leonor had begun singing songs he had never heard—melodies from barracks—songs workers sang while cutting cane—songs in a blend of Spanish and African tongues that had survived generations.

“Where did you learn that song?” Vicente asked one afternoon.

Leonor startled—like caught doing something forbidden.

“I don’t know—perhaps I heard it in the market.”

Lie.

Vicente knew immediately.

She rarely went—and when she did, surrounded by servants protecting her from contact.

He watched her more closely—instructed maids to report her every movement—every conversation—every time she left the house.

Nothing concrete emerged.

Yet the feeling of something slipping grew like a tumor.

In the seventh month, Father Ruiz visited—monthly inspection—to ensure boundaries held.

He sat with Vicente and Leonor—discussed pregnancy, preparations, immediate baptism.

“Everything proceeds satisfactorily,” Ruiz said.

“The child will be born in about two months—and then your situation normalizes completely.

Has the man been transferred?”

“Not yet,” Vicente said.

“I have contacts in Kingston—coffee plantation needs workers.

He will be sold immediately after the birth.”

“Good,” Ruiz said.

“He must not remain.

Emotional complications must be avoided.”

After Ruiz left, Vicente called Mateo to his study—the first direct conversation since the nightly visits ended.

Mateo entered thinner—constant work under sun had darkened his skin—his eyes still held that unsettling intelligence.

“In two months you will be sold,” Vicente said bluntly.

“To a coffee plantation in Jamaica.

Work there is hard.

If you behave—productive—you will live acceptably.

Do you understand?”

“I understand, sir.”

“And understand this: if you attempt to contact anyone from this property—before or after—you will suffer consequences—not only you—anyone you contact will suffer.”

The threat was clear: if Mateo tried to reach Leonor—she would suffer.

“There will be no contact, sir.”

Vicente studied his face—for resentment, rage, designs of revenge.

Mateo had learned in twenty-six years to hide thoughts behind submission’s mask.

“You may withdraw.”

Vicente poured another rum—third of the afternoon—drinking more lately—needing numbness—silencing voices telling him he’d made a terrible mistake—that he had opened a door he could never close.

The eighth month brought suffocating heat—air heavy.

Leonor spent hours on the shaded gallery—constantly fanning—belly enormous—every movement difficult.

Vicente hired a Havana midwife—three decades of experience—to attend the birth.

Dr.

Morales was on call to travel if complications arose.

The nursery waited—Spanish furniture—tiny clothes folded—carved mahogany cradle that had belonged to Vicente’s father.

Only the birth—and the removal of the loose end—remained.

Vicente completed the sale arrangements—Kingston buyer agreed to pay two hundred pesos plus transport.

Mateo would ship three days after the birth—enough time to verify a healthy baby—not enough to allow complications.

One late October afternoon—Vicente reviewing documents in his study—a maid knocked—urgent.

“Sir—the baby.”

Vicente ran upstairs—heart pounding in his ears.

Leonor on the bed—face contorted with pain—sheets stained—midwife organizing towels, hot water, instruments—efficient movement.

“Leave, Don Vicente,” the midwife said.

“Men do not belong here.

Return in a few hours.”

Vicente wanted to stay—wanted to witness the birth as he had witnessed conception—his right—his duty.

“Sir,” the midwife insisted.

“You obstruct—for your wife’s sake—leave.”

Reluctantly—Vicente obeyed.

He descended to the salon—poured rum—drank—poured more—paced—listened to screams from upstairs—more frequent—more intense.

Hours passed agonizingly slowly.

Sun vanished—night fell—candles lit—screams continued.

Near eleven—another sound joined—sharp cry of a newborn.

Vicente took the stairs two at a time—entered without permission.

The midwife cleaned a small reddened body—wrapped in white cloth—the baby cried strong—healthy lungs—life claiming space.

“A boy,” the midwife announced—smiling.

“Strong and healthy.

Congratulations, Don Vicente.”

Vicente stepped closer—extended arms—the midwife placed the wrapped infant in his hands—and then he saw.

The baby’s eyes—briefly open—were light.

Not the dark Salazar eyes of four generations—light eyes like Mateo’s.

The floor shifted beneath Vicente.

Of course the baby’s eyes were light—what had he expected? Mateo was biological father.

Knowing it intellectually was one thing—seeing physical evidence in his hands another.

“It is perfectly normal,” the midwife said, noticing his expression.

“Many babies are born with light eyes—they darken in months.

Do not worry—they will probably change.”

Vicente nodded without conviction—went to the bed—Leonor exhausted—hair stuck with sweat.

When she saw the baby—her face transformed—light entered her eyes—softness he didn’t remember ever seeing.

“Give me my son,” Leonor whispered—arms open.

He placed the baby in her arms—and saw something that chilled him: the way she looked at the baby—the way her fingers traced the tiny face—the way she smiled despite pain.

It was the same way she had begun to look at Mateo—recognition.

“He will be named Vicente,” Vicente said—voice hard.

“Vicente Armando Salazar Junior—my heir—my son.”

Leonor said nothing—only looked at the baby—caressed his small hand—whispering words Vicente could not hear.

Days blurred with activity.

Baptism—Father Ruiz officiating—baby registered as legitimate son of Vicente and Leonor—telegrams to Havana—modest celebrations.

Everything proceeded as planned—except one detail.

During postpartum rest—when Leonor should remain in bed—Vicente noticed maids entering and leaving her room more than usual—bringing food, water, clean baby clothes.

One afternoon he stopped a maid—bundle wrapped in cloth in her arms.

“What is that?” he asked.

The maid paled.

“Only—only dirty clothes, sir—for washing.”

“Show me.”

Hands trembling—the maid unwrapped the cloth—inside: dirty clothes—and a folded paper.

Vicente snatched it—unfolded—read.

Leonor’s educated script addressed to Mateo.

“Mateo—our son was born last night.

He is beautiful—strong—with your eyes.

When I look at him, I see your face—and my heart breaks—knowing you can never know him—never hold him—never be called father by this child who is yours in every way that truly matters.

Vicente plans to sell you in two days—send you far where we will never see you.

I cannot allow that.

I cannot live the rest of my life knowing you exist somewhere—suffering—while I live in this gilded cage.

I have made arrangements—I have money hidden—jewels I can sell.

In three nights—when Vicente is in his study drinking as he does every night—we will escape—you, me, and the baby.

There is a ship from Matanzas to Charleston.

The city is full of freed people.

We can disappear—start anew—be a family.

I know it is dangerous—I know we may die trying—but I would rather die free with you than live one more day as the wife of the man who treats you like animal.

Wait for my signal—three lights in my window—then come—and we will execute our plan.

We will destroy this place that chained us both.

I will burn San Cristóbal to the foundations if necessary.

— L.”

Vicente read it three times.

Each word a nail in his heart—a poison in his blood—a confirmation of everything he feared.

Not only had they betrayed him—they planned to destroy him completely.

“Where did you get this?” he asked—dangerously calm.

“Doña Leonor asked me—asked me to deliver it to a worker—to give it to Mateo,” the maid stammered.

Vicente finished her sentence.

“Yes, sir.

I’m sorry—she threatened—”

“Get out of my sight,” he snapped.

“If you say a word to anyone—I will sell you to the port brothels.

Understand?”

“Yes, sir.” She fled—crying.

Vicente went to his study—locked the door—sat—and, for the first time in fifty-two years, cried—crying not sad tears—but rage—pure—concentrated—acid in his chest.

He had given everything for an heir; sacrificed pride, dignity, peace of mind; endured months of humiliation watching another man with his wife.

This was his payment: betrayal—escape—destruction.

Leonor did not love the baby because he was hers; she loved him because he was Mateo’s.

And Mateo had played perfectly—the obedient slave—following orders—seducing his wife—planting rebellion—planning to steal everything.

No, Vicente thought.

No.

He stood—left the house—walked to barracks—where he knew he’d find the men he trusted for the worst tasks—thirteen capable men—loyal—who owed their position to Vicente—who would do what he ordered without questions.

“Come with me,” he said.

“A problem requires immediate resolution.”

They followed.

He led them to a separate building—at the property’s edge—a place they knew—but preferred to forget—the correction house—where rebellious or escaping workers were taken for discipline—thick stone walls—no windows—only a heavy iron-reinforced door.

Inside were instruments designed to cause maximum pain with minimal permanent damage—at least in theory.

In practice, many did not survive long enough for permanent damage to matter.

“Bring Mateo,” Vicente ordered.

“Now.”

Two men ran.

Vicente lit oil lamps—yellow light revealed dark stains on stone—stains water could not remove.

Five minutes later, Mateo arrived—confused—shirtless—barefoot—dragged from his cot.

“Sir,” he asked cautiously.

Vicente did not answer—only nodded to men who immediately seized Mateo—dragged him to the room’s center—forced him to his knees.

Vicente spoke.

“You thought you were clever—planning your little escape—steal my wife—steal my son—destroy my property—and I would never discover it.”

Mateo’s eyes widened—understanding.

“Sir—I—”

“Silence,” Vicente roared.

“I read the letter.

I know everything.

I know you seduced my wife—filled her with escape—planned to burn San Cristóbal.”

Mateo did not deny—knew it was useless.

“I did what you ordered,” he said instead.

“I followed every instruction.”

“To give me an heir,” Vicente shouted.

“Not to steal my wife’s affection—nor conspire.”

“What did you expect?” Mateo’s voice rose.

“That I sleep with her night after night—touch her—know her—and feel nothing? That she feel nothing? We are human—not animals who mate without consequence.”

“You are my property,” Vicente hissed—stepping until their faces were inches apart.

“You have no right to feelings—no right to plans—no right to anything but obedience.”

“Then you should have chosen your instrument better,” Mateo answered, “because now you have a son who is not yours—and a wife who will never look at you as husband.”

It was too much.

Vicente struck him with the back of his hand—impact resonated—blood from Mateo’s split lip—eyes held no fear—only defiance.

“Bring Doña Leonor,” Vicente ordered—“with the baby.

I want her to see this.”

“Sir,” one captain protested, “are you sure? She just gave birth—it may not be appropriate—”

“Do it.

Now.”

The captain ran.

Fifteen minutes of tense silence.

Mateo remained kneeling—held by two men—Vicente paced like a caged animal—others waited—fearful of movement.

Footsteps outside—door opened—Leonor entered—carrying the baby—pale—weak—eyes burning with immediate comprehension.

“Please,” she whispered—“please.”

“Silence,” Vicente ordered.

“You came here to see the consequences of your betrayal—to understand there is no escape—no future where you and that—” he gestured—“are together.”

Leonor pressed the baby to her chest.

“Do not hurt him,” she begged.

“Please.

He only did what you ordered.”

“Exactly,” Vicente said.

“He did what I ordered—and now he will do what I order again: pay for his insolence—for presumption—for daring to touch what does not belong to him in any way except the most mechanical.”

He walked to a table arranged with correction instruments—picked up a curved knife.

“No!” Leonor screamed.

“No—please—I beg you.

It was my fault—I wrote the letter—I planned it—punish me—”

“Oh, I will punish you,” Vicente said.

“I will punish you by making you watch—as I watched for months.

Now you will feel what it is to be forced to witness something that tears your soul.”

He turned to Mateo.

“Hold him,” he ordered.

What happened in that room over the next hours would never be forgotten.

Vicente did not kill Mateo—that would have been mercy.

He executed a calculated revenge designed to destroy not only body—but spirit.

He did it methodically—almost scientifically.

Using knowledge acquired over decades of handling human property—he knew exactly how to cause maximum suffering.

Leonor was forced to watch—baby in arms—crying—screaming—begging.

The men held her; kept her there—Vicente ordering that she not look away—her punishment to see what her love had caused—to see the consequences of defying their order.

When finally finished—Mateo was no longer the same—physically and psychologically broken in ways time could not repair.

Vicente wiped his hands on a rag.

“Take him,” he ordered.

“He has a ship tomorrow—copper mines—eighteen months life expectancy.

If he survives that long, God has a twisted sense of humor.”

They dragged Mateo’s semi-conscious body out.

Vicente stepped to Leonor—sobbing uncontrollably—the baby crying.

“Now listen carefully,” he said—voice ice—“that child is my son—Vicente Salazar Junior.

He will be raised a Salazar—educated a Salazar—inheriting San Cristóbal as a Salazar.

You will never—never—mention that man’s name in his presence.

You will never tell him the truth.

You will live the rest of your life as my wife—fulfilling social duties—burying whatever feeling you developed in the deepest place of your heart.

Do you understand?”

Leonor didn’t answer—only cradled the baby—rocking—trying to calm him.

“Answer me.”

“Yes,” she whispered.

“I understand.”

“Good.

Return to your room—rest—recover—because in two weeks we receive visitors from Havana—and I need you to look like the happy wife of a man who finally has an heir.”

Leonor staggered out—maid holding her when her legs threatened to fail.

Vicente remained alone in the correction house—stared at fresh stains that would join old—layers of violence accumulated through years.

He took a bottle of rum kept there for such occasions—drank straight—liquid burning his throat.

He had won—kept control—protected property, honor, future.

So why did he feel like he had lost everything?

Two days later, Mateo was shipped—barely conscious—wrapped in stained cloth—loaded like any other cargo.

The ship captain—who had transported thousands—asked no questions.

In his business—questions were dangerous.

San Cristóbal returned to routine.

Work in fields continued—cane cut—sugar produced—profits.

Leonor performed her role—attended to little Vicente with obsessive dedication—appeared at social events—smiled when expected—but something fundamental had broken.

Those who knew her noticed—light in her eyes gone—movement like an automaton—fulfilling functions without presence.

Vicente was not the same—drank more—slept less—spent hours in his study staring at papers unsighted—woke sweating at night—haunted by dreams where he was the one tied—observed—screaming—no one coming.

The baby grew.

His eyes never darkened as predicted.

They remained light.

Every time Vicente looked—he saw Mateo—and something twisted inside him—love and hate so intense he could hardly breathe—he loved the child—his heir—his future—everything he had worked for—and he hated what the child represented—his failure—his humiliation—his inability to be a “complete” man.

Years passed.

Vicente Junior grew strong—smart—reading at four—riding at six—accompanying Vicente at eight—learning the business.

Yet the boy was different—something made Vicente uncomfortable.

He showed compassion toward workers—asked why they had to work so many hours—why they could not learn to read—“Because that is the natural order,” Vicente explained.

“Some are born to command; others to obey.

You were born for the first; they for the second.”

The boy didn’t seem convinced.

Leonor watched from a distance—and a small flame of hope flickered in her stilled chest.

Perhaps her son would be different—perhaps he would break the cycle.

In 1860, at twelve, everything began to change—Cuba stirred—abolition ideas filtered onto the island—whispers of rebellion—change.

Vicente ignored it—believed his world eternal.

Workers did not ignore—especially those who knew how to read—taught in secret—passing forbidden books at night.

One of them—a young man named Domingo—approached Vicente Junior one afternoon—while the boy read under a garden tree.

“Young master,” Domingo said carefully.

“May I ask something?”

“Of course,” the boy answered.

“Is it true that elsewhere—people like me are free—that we go where we want—work where we want—have families without fear of being separated?”

The boy thought.

“That’s what the books say,” he said.

“In the United States—there are free states.

In England—slavery no longer exists.

My tutor has told me.”

“And do you think that is right—or do you think like your father—that we should be property?”

Dangerous question—the kind that could cost Domingo weeks in the correction house.

The boy answered with twelve-year-old honesty: “I don’t know.

Sometimes I think that if I had been born in your place—I would want to be free.

But my father says such thoughts are dangerous.”

Domingo nodded and left before anyone noticed—planting something in Vicente Junior—a seed of doubt—that grew.

In 1868—at twenty—Cuba exploded—the Ten Years’ War—independence from Spain—and a war over slavery—about who had the right to freedom.

Plantations attacked—burned—looted.

Owners fled to Havana or the United States.

Those who remained met varied destinies—some negotiated—others fought—many died.

Now sixty-nine, Vicente stayed—San Cristóbal was his life—legacy—he would not flee—fortified the great house—armed loyal overseers—prepared to defend.

Leonor—now sixty-six—watched with strange calm—as if something she had waited for was finally arriving.

Vicente Junior had been sent to Havana for study—returned against his father’s wishes.

“I can’t leave you,” he said.

“You’re my father.

This is my home.” Vicente felt pride—and sadness—his heir—for whom he had sacrificed—had grown strong and loyal—and yet had something else—softness not weakness—something more complex.

Attacks began October 1868—small at first—night raids—stock theft—field burning.

Vicente responded with increased violence—captured two rebels—executed them publicly as warning—warnings did not work—they increased resolve.

In December—final attack: one hundred men—former slaves from nearby plantations—escaped workers—rebels with machetes, old rifles, torches—came at dawn—fog covered fields like shroud.

Vicente woke to gunshots—screams—fire crackle—dressed quickly—took his rifle—ran down—house surrounded—barracks already burning—columns of black smoke climbing gray dawn—overseers who tried to defend lay dead—or had fled.

Vicente Junior appeared on stairs—armed.

“Father—we have to leave.

We can’t defend this.”

“No,” Vicente roared.

“This is my land.

No one will take it.”

Leonor descended—white nightgown—hair loose—ghost of another time.

“Vicente,” she said—voice serene—“it is over.

Let it go.

Let it burn.”

“Are you insane?” Vicente shouted.

“This is San Cristóbal—everything we have.”

“No,” Leonor said.

“It is everything you have.

I lost everything I had twenty years ago—in a room where I was forced to watch as you destroyed the only man I loved.”

Silence—except fire outside.

“What is she talking about?” Vicente Junior asked.

“Nothing,” Vicente said quickly.

“She is in shock—she doesn’t know—”

Leonor’s calm held.

“Your father is not your biological father,” she said—looking directly at her son.

“He cannot have children.

He never could.

He chose a slave to fulfill that function—a man named Mateo.

He is your true father.”

The boy stepped back as if struck.

“That is a lie,” Vicente said.

“She is lying—she is trying to destroy me.”

Leonor laughed—a bitter laugh without humor.

“Destroy you? You are already destroyed, Vicente—since the day the doctor told you the truth.

Everything you did since—all the cruelty—all the control—all the pain—was to hide your shame—and your failure.”

“Shut up,” Vicente screamed—raising his rifle.

“Shoot me,” Leonor said—without fear.

“Do me a favor—free me from the prison my life has been for forty years.”

“Father,” Vicente Junior stepped between them.

“Lower the gun.”

“Move,” Vicente said.

“No,” the boy said—held his position.

“I will not let you harm her.”

Outside—screams grew closer—great house doors battered—wood splintering under axes and machetes.

“It does not matter anymore,” Leonor said.

“They are coming—it is finished.”

Doors gave—rebels flooded—faces marked by sun and suffering—eyes burning with rage gathered across generations.

At their front—Domingo—the same who had spoken with the boy years before—now thirty-something—leader—with machete and torch.

“Don Vicente Salazar,” he said—voice trembling with contained emotion.

“Your time is up.”

Vicente aimed; the boy moved faster—knocked the rifle downward—the shot hit the floor—splinters flew.

“What are you doing?” Vicente shouted.

“Saving you from yourself,” the boy said.

“This is over.

You will cause no more deaths.”

He turned to Domingo.

“Take what you want—burn what you want—but let us go—my mother—my father—me—let us leave alive.”

Domingo looked at the boy—then at Vicente—then at Leonor.

“The lady may leave,” he said.

“You too, young master.” He pointed at Vicente.

“He stays.

He must answer for what he did—what he did to all of us.”

The boy shook his head.

“I cannot let you kill him.”

“We will not kill him,” Domingo said.

“That would be mercy.

We will leave him here—alive—to watch everything he built—everything he valued—everything he sacrificed—turned to ash.”

Destruction became systematic—rebels looted—broke furniture—smashed paintings—took what had value—destroyed what didn’t—the library took especial rage—books forbidden to workers tossed into fire—deeds—ownership papers—burned—feeding flames.

Leonor watched—serene—almost happy.

The boy tried to save things—futile—like stopping flood by hand.

Vicente was tied to a chair—forced to watch—everything he had—everything that meant—erased.

Domingo approached as fire climbed.

“Do you know who Mateo was?” he asked.

Vicente did not respond.

“He was my uncle—my grandmother’s son—he taught us to read in secret—he said one day we would be free.

When you destroyed him—sent him to die in Jamaica—we swore we would avenge his suffering.”

“Mateo survived,” Vicente finally said—voice broken.

“He died after six months in the mines,” Domingo said.

“But before he died—he wrote letters—letters passed hand to hand—letters telling his story—telling of the child left behind—the child you registered as yours.

He never forgot his boy—he never forgot Doña Leonor.”

Tears ran down Vicente’s face—not sorrow—but impotent rage.

“Kill me,” he whispered.

“End it.”

“No.” Domingo sliced the ropes—freed him.

“You will live—to see the new world we build on the ruins of yours.”

Rebels withdrew—house burning—Vicente stood amid the growing fire—free to move—free to flee—free to save himself.

Outside—a carriage waited to carry Leonor and the boy to Havana.

“Father,” the boy shouted.

“Come!”

He did not move—stared at flames consuming his study—his room—the hallways he had walked fifty years.

“I have nowhere to go,” he shouted back.

“This was all I was.

Without San Cristóbal—I am nothing.”

“Don’t be foolish,” the boy barked—ran toward the house—rebels held him—pulled him back.

“He has chosen,” Domingo said.

“Let him have his choice.”

The boy struggled—useless—one against many.

Leonor took his arm.

“Let him go,” she whispered.

“Some men cannot live outside the prisons they build.

He chose this prison—now he chooses to die in it.”

The roof collapsed—burning beams fell—white columns cracked and toppled—and within—still visible for a second through flames—Vicente—standing—motionless—watching his world burn—as he had watched so many things burn in his life—the last image his son had of him—a dark silhouette in fire—disappearing into smoke.

Domingo ordered the carriage to depart—carrying Leonor and the boy—toward Havana—toward an uncertain future—free of San Cristóbal.

Years after were chaos—and transformation.

War continued until 1878—ten years of struggle—devastated the island—irreversibly changed it—slavery gradually abolished—first partially—then completely—large plantations divided—redistributed—transformed.

Leonor and her son lived in Havana in a small apartment—far from San Cristóbal’s opulence.

Leonor spoke little of what had happened—seemed to have found some peace—embroidered—read—walked along the Malecón—died quietly in her sleep in 1875—at seventy-two—last wish: buried with a small medallion containing a lock of hair—light hair—the boy knew was not Vicente’s.

After her death, the boy began searching answers—investigated everything he could about Mateo—spoke with former workers of San Cristóbal—now free—reconstructed the story his mother had not fully told—and discovered something else—discovered that before he died—Mateo had written not only letters—but a detailed diary—documenting everything: the forced nights in the marital room—with Vicente watching—the feelings that grew for Leonor—the plans—the torture in the correction house—everything there—in shaky script written in final weeks before the mines killed him.

The diary had been preserved—passed in secret—Cuba to Jamaica and back—kept as testimony—reminder of the horrors of a system collapsing.

The boy read every word—cried every page—and made a decision: he changed his legal name from Vicente Armando Salazar Junior to Mateo Vicente Salazar—adopted his biological father’s name—honored him publicly for the first time—declared to the world who he truly was.

The remaining aristocracy was scandalized—surviving Salazars—distant cousins—disinherited him—called him traitor to class—to race—to everything they represented.

Mateo Vicente did not care—with money salvaged from San Cristóbal’s ashes—he bought land—not to make another plantation—but something radically different.

In 1880, on the exact site where San Cristóbal had stood, he established Cuba’s first community of free farmers—a cooperative where former slaves could work their own land—grow their own food—live with dignity.

It wasn’t easy—first years brutal—drought—pests—opposition from planters who saw threat—but Mateo persisted—worked shoulder-to-shoulder—not as master—but equal—shared profits—built a school—for children and adults—to learn to read.

Domingo—the rebel leader—became his right hand—friend—brother in everything but blood—the community grew—other families joined—by 1890—over two hundred people lived and worked there—and at the property’s center—where the great house had stood—Mateo built a monument—not large—not elaborate—only a simple stone with names—names of all the people enslaved at San Cristóbal during fifty years—one hundred forty-three under Vicente—and names of earlier generations—those owned by Vicente’s father—grandfather—three hundred twelve names in total—and at the top—larger letters—three names:

Mateo—Father.

Leonor—Mother.

Vicente—Who chose destruction over redemption.

In 1898—when Cuba finally gained independence—Mateo, fifty—was invited to Havana for celebration—among heroes who made the new country possible—he declined—sent a letter to the new government—read publicly—later preserved in national archives.

“True freedom,” he wrote, “is not won only on battlefields—but in the hearts of men willing to see humanity where they once saw property.

My father Vicente Salazar had the chance to do that—to grow beyond the limitations of his time—his class—his faults.

He chose to cling to a dying world—and died with it.

I do not judge him—I understand he was a product of a system formed at birth.

But I do not honor him—because he had choices he did not take—opportunities for mercy he rejected.

I build in the ruins he left—not as vengeance—but promise.

The promise that the suffering so many endured under systems like the one he perpetuated will never be forgotten—never minimized—and never—ever—repeated.

This land where sugar was grown with tears and blood now grows food feeding free mouths.

This land where spirits were broken now strengthens communities.

That is my legacy—not the surname falsely given—but the work I choose every day—in memory of my true father Mateo—who loved where he was told only to obey—who dreamed where he was told only to work—who died far from everything he loved—but whose spirit lives in every child learning to read—in every family working its own land—in every person living with dignity instead of chains.”

Mateo Vicente died in 1923 at seventy-five—surrounded by three generations of the community he helped build—buried between Leonor and an empty space where Vicente theoretically should be—but left deliberately empty—reminder of absence—of opportunities lost—of a man who chose pride over everything.

San Cristóbal’s story—of a sterile master who destroyed everything to keep control—of a wife who found love where obligation was prescribed—of a slave used as tool who refused to remain only that—of a son who transformed inherited trauma into a legacy of freedom—is a story Cuba tried to forget for decades—too uncomfortable—too complex—ill-fitting simplified narratives of the past.

Descendants of slaveholding families didn’t want to remember the cruelty their ancestors perpetuated; descendants of enslaved didn’t want to relive trauma—and everyone preferred not to face impossible situations—decisions with no good options—tragedies born when inhuman systems distort everyone they touch.

But the community Mateo founded—eventually known as Villa Libertad—preserved the story—passed generation to generation—not as fairy tale with neat heroes and villains—but as reminder of complicated truths: that Vicente was victim and victimizer; Leonor accomplice and prisoner; Mateo used and loved; and Mateo Vicente inherited trauma and opportunity in equal measure; that all their lives were shaped by forces larger than any individual—economic systems valuing sugar over humanity—social hierarchies elevating some and crushing others—ideas of race, class, and power distorting everything.

In 1971, cataloging historic sites, government researchers visited Villa Libertad—found the monument of three hundred twelve names—found carefully preserved documents in the community library—Mateo’s diary—Leonor’s letters—even some of Vicente’s papers saved from fire—and found something more: a sealed box—with instructions not to open until 1970—containing a final letter from Mateo Vicente—written in 1920—three years before his death—reflecting on his life, decisions, legacy—ending:

“I have spent seventy years asking whether a life born of such cruelty and humiliation has value—or whether I am fundamentally stained by my conception.

I have concluded I ask the wrong thing.

The question is not whether origins define me—but whether my actions do.

Vicente Salazar created me to serve his ego—to fill a void his body could not—but I chose to create something different.

I chose to use the life given—no matter how horrible the process—to build something he could never imagine.

Perhaps that is the final revenge—not destroying him—but surpassing him—not hating his memory—but making it irrelevant by building something so deeply different comparisons become absurd.

To those who come after—born of circumstances you did not choose—carrying traumas you did not create—inheriting legacies you did not ask for—I say: you are not your origins.

You are your decisions—what you build with the hands you were given—even if those hands were formed in violence.

Choose to build beauty.

Choose to create freedom.

Choose to be more than the world expected of you.

That is the only triumph that truly matters.”

Villa Libertad still exists today—a thriving agricultural community in Cuba.

Almost no one outside the region knows its complete history—its extraordinary, terrible origin—but those who live there remember—teach their children—preserve it as reminder of where they came from—and why they must never return there.

And the memory of that room—of the forced nights—of the watching—of the whispered thank you—of the fluids and breaths and the addiction to humiliation—and of a letter hidden in a bundle—remains a quiet lesson beneath all the rest: that coercion warps everything it touches—that love is most dangerous when it grows in the dark—seen by eyes that cannot admit what they are seeing.

News

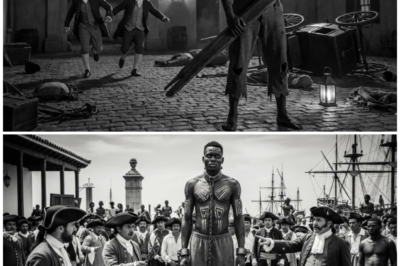

The 7’6 Giant Who Made His Masters Flee: Cartagena’s Most Disturbing Story (1782)

The 7’6 Giant Who Made His Masters Flee: Cartagena’s Most Disturbing Story (1782) On the night of August 15, 1782,…

The Most Beautiful Slave Who Seduced Seven Wives — and Changed Their Destinies Forever (Cuba, 1831)

In April of 1831, seven wives of sugar planters in Matanzas, Cuba, killed their husbands within the same breathless, bitter…

Master Bought an Obese Slave Girl to His Room, Unaware She Had Planned Her Revenge

Master Thomas Caldwell purchased Eliza on a sweltering June afternoon, his eyes sliding over her large frame as he counted…

The Runaway Slave Woman Who Outsmarted Every Hunter in Georgia, No One Returned

Here’s a complete story in US English, structured with clarity and pacing, and without icons. The Runaway Slave Woman Who…

The Countess Who Gave Birth to a Black Son: The Scandal That Destroyed Cuba’s Most Powerful Family

Here’s a clear, complete short story in US English, shaped from your draft. It keeps the historical spine, the courtroom…

The Slave Who Had 6 Children with the President of the United States — He Loved Her for 38 Years

Here’s a complete, self-contained short story shaped from your draft. I’ve kept the voice intimate and steady, built the plan’s…

End of content

No more pages to load