The Newse River crawled through the coastal plain, lugging silt and secrets.

Tobacco leaves shimmered under a white sky.

The work was endless, and the wealth was carved from suffering.

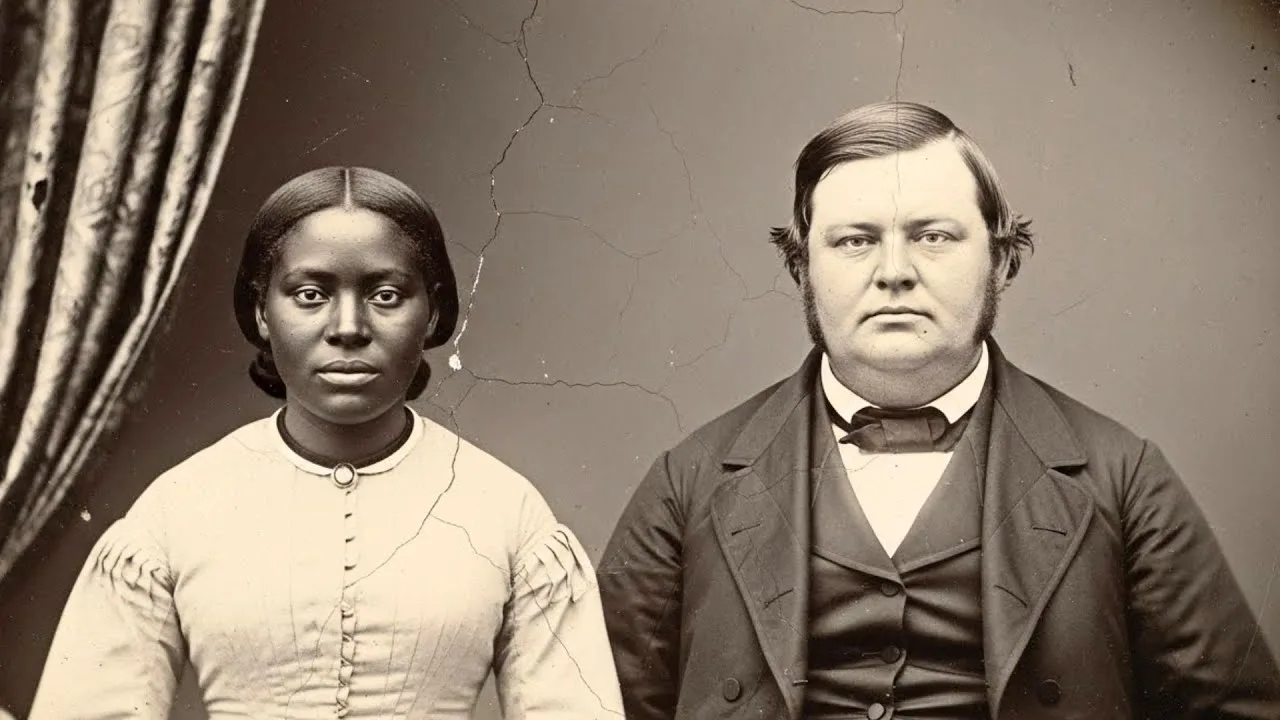

On a blistering afternoon, Harrison Peton stood in the great room of Peton House and made a declaration that stalled the air.

He would place his only son, William—twenty-six, nearly three hundred forty pounds—under the complete authority of an enslaved woman named Mercy.

Not a caretaker.

Not a companion.

A guardian with absolute control over his daily life, his food, his movement, his routines.

For half a year, the scion of the Peton dynasty would live at the command of a woman his family owned.

Newburn’s white society gaped.

The whispers were quick and cruel.

Some suspected a morbid medical experiment; others said religion had driven Harrison mad.

No one grasped the truth.

No one saw the chain of events already sliding into place that would transform William’s body, shred a hidden order of men, and turn Peton House to ash.

Mercy: What Knowledge Survives

Mercy was born in 1814 in a world that measured humanity by prices.

Her mother, Abigail, cooked in the big house and moved with the quiet authority of someone who knew everyone’s appetites—culinary and otherwise.

From kitchen corners and corridor shadows, Mercy watched young Harrison’s tutors, stole letters with her eyes, learned words she was forbidden to know.

Education was a weapon her mother could not buy but insisted her daughter acquire.

Her grandmother taught roots and body physics: which herbs cool fever and which heat a blood, which flowers mask pain and which reveal it.

Old women taught conjure that survived ocean crossings and auction blocks—rituals never written down because writing could be seized.

Mercy learned to deliver babies and turn coughs into breath.

By twenty, she was the plantation’s midwife and healer, tolerated by white doctors who preferred her results to their pride.

In 1843, Mercy birthed a daughter, Grace.

No father was named.

Grace was bright, quick, as luminous as a child can be in a place designed to extinguish light.

For six years Mercy loved her with terror, knowing love was the most valuable leverage in Bowfort County.

Then, in the autumn of 1849, while Harrison traveled, William was drunk.

He found the child near the tobacco barn.

Three hours later, they found Grace broken, discarded in a building that stored wealth where breath should have been.

The overseers were hardened men; even they looked ill.

Harrison returned and did what powerful men do.

He converted atrocity into accident.

Grace fell from a loft, he said.

William was sent away to “recover” from the shock, his bloody clothing burned, his future unburdened.

Mercy was given a week to grieve under watch.

There was no funeral.

Dirt was dirt.

Grace lay under it.

The grief did not fade.

It calcified into patience.

—

## The Order: Crowned Men, Predatory Nights

Bowfort County’s influence had a spine the public could not see.

The Order of the Crimson Crown—seventeen men threading law, commerce, and ritual into one rope.

They believed consuming the vulnerable gave them power over life and death.

Their symbol was a snake eating itself, wrapped around thorns: hunger justified by suffering.

Harrison had been initiated in 1830.

He attended ritual gatherings in the cellar beneath Peton House and learned that men who controlled sheriffs and judges could turn human cries into silence.

In July 1852, a letter arrived on black-waxed parchment.

Someone had talked.

William’s erratic fits had carried phrases he should not have known.

The Order demanded proof that Harrison remained obedient—and that his son would keep his mouth shut.

Mercy would be assigned absolute authority over William for six months.

The humiliation would be public, explained as a radical cure for gluttony and melancholia.

If Harrison complied, the Order would smother any investigation.

If he refused, accidents would happen to him and to his son.

Harrison wrote his acceptance before dawn.

The second letter named Mercy.

—

## Day One: No

Mercy knocked on William’s door at eight in the morning on July 14.

No answer.

She opened the door, and the smell bowed her back—a saturation of sweat, sour chamber pots, plates crusted with gravy.

William lay in bed like a drowned man who hadn’t learned he was dead.

“Bring breakfast,” he said without looking up.

“Ham.

Eggs.

Biscuits.

Gravy.

Coffee—cream and sugar.”

“No,” Mercy said.

Silence reversed in the room.

“I’ll have you whipped.”

“Your father gave me authority.

If you refuse my instructions, he will enforce them.”

William blinked, unused to a world where someone could deny him.

She pulled the curtains until light invaded.

He raised an arm to shield his eyes.

Mercy took stock like a physician and like a woman who had lived twenty years with men and their violences.

She named his symptoms: breath slicing thin on stairs, heart failing under excess, shoes he could not tie, a face swelling toward suffocation.

He tried to rage.

She did not flinch.

“Get up,” Mercy said.

“Your bath water is heating.”

Mercy and two house men lifted and washed him.

Fatigue cracked his voice like dry wood.

He dressed with help.

He descended the stairs in slow agony.

At the table, Mercy set a boiled egg, a small piece of dry toast, half an apple, weak tea without sugar or cream.

“I’ll starve,” he said.

“You have been starving,” Mercy said, “while you fed yourself to death.

This is correction.”

They walked.

Two hundred yards.

Five stops.

Tomorrow: farther.

Routine and Tincture

Mercy built a schedule tight enough to hold: six a.m., washing and dressing; a simple breakfast; walking until breath returned.

She gave him protein in measured portions, vegetables cooked and raw, fruit without the sugared lies he craved.

Bread scarce.

Alcohol gone.

He bribed servants for food; the servants told Mercy; she reduced his portions.

He called it torture.

She called it adulthood.

At night, Mercy added tinctures to his tea—roots and herbs arranged in ratios that would open doors in the mind.

Nothing lethal.

The first step was remembering.

Week two brought dreams that felt like trespasses.

William saw a child at the foot of his bed.

A small figure with dark hair, silent, saturated with bewildered pain.

In daylight, she appeared in glass reflections, under trees, just beyond sight.

He told Mercy.

She told him bodies release toxins as they correct years of damage; perception shifts.

He looked at her and didn’t believe it.

By week three, the scale tipped in his favor: seventy pounds gone, breath less ragged, skin less inflamed.

He asked questions that were not about breakfast.

“Do you have family?” he asked.

“I had a daughter,” Mercy said.

“She died three years ago.”

“I’m sorry,” William said.

Mercy held his gaze.

“Are you?”

Something faltered under his ribs.

“How did she—”

“She was killed.”

“By whom?”

“Do you truly not remember, Master William?”

His body recognized the truth before his mouth did.

He collapsed on his knees in the grass and retched the years out—grease and shame, liquor, lies.

Mercy watched like granite.

“Now you remember,” she said.

He cried until the dirt held it.

He begged.

Mercy did not grant forgiveness; neither did the child at his bed.

—

## The Cellar and the Ledger

Harrison visited and admired a leaner son.

William tried to tell him about the child.

Harrison ordered him back into silence.

Accident.

History.

Forgetting as policy.

That night, Mercy widened the tincture’s doorway.

The dead do not disappear.

The living refuse to look.

William came to her in the garden, terrified.

“Tell me how to make it right.”

“You cannot,” Mercy said.

“But you can make it meaningful.”

There was a ledger beneath Peton House—the Order’s book of crimes, names and rituals recorded with bureaucratic cruelty.

William knew the way.

Mercy had allies: seven enslaved men and women who had lost too much to remain still.

They waited until Harrison left for Wilmington.

At midnight, they opened a wall in the pantry with a sequence of stones.

The cellar breathed old smoke and dried blood.

Robes hung like insomnia.

At the far wall, a second door opened into the chamber where record became confession.

The ledger was bound in a leather that looked like skin; iron held it shut.

They read.

Dates and names from 1809.

Forty-three murders.

Methods described without flinch.

Judges, reverends, mayors balancing their sins with civic speeches.

They copied until dawn—entries that would destroy men if shared.

Then Harrison’s voice rose upstairs.

Mercy sent them into the root cellar tunnel and reset the wall.

Harrison gazed at her by lamplight.

“What are you doing down here?”

“Collecting ingredients for a remedy,” she said, and held his eyes until he blinked.

Upstairs, William lay in bed performing sleep while his father stood over him.

Harrison left.

For now, the world remained unburned.

—

## Discovery and Chains

They planned to move the evidence north—multiple newspapers, multiple prosecutors, abolitionists who could cut through Bowfort County’s web.

William would be the courier, traveling under his father’s expectations.

Mercy warned him he could never return.

William said he did not want to.

On October 15, the night before departure, Harrison arrived at Mercy’s cabin with six Order men.

They ransacked the floorboards and found the copies.

They burned them while Mercy watched justice go black.

“Take her to the cellar,” Harrison said.

“We have a ritual tomorrow.”

They chained Mercy to the stone altar in darkness, a body held in place by men who believed ownership meant God.

Harrison told her she was property.

He told her power in this county was a kind of blood in his veins.

He left her to learn fear under ground.

He did not understand what networks had already moved to surround his house.

Samuel told everyone.

By midnight, three dozen enslaved people circled Peton House—axes and sickles in their fists, resolve hotter than lamp oil.

Three white overseers joined them, men who had spent years pretending loyalty to a system they no longer could stomach.

William stood among them, rifle in hand, the house soaked in oil.

Fire and Reckoning

At twelve, the Order gathered in the cellar.

They lit candles and began their ritual, confident they were untouchable.

Fire answered arrogance and took the stairs first, licked the boards, swallowed doors.

Smoke rolled down into the cave of their cruelty.

William led the others through the kitchen and down the alternate route.

The battle was neither ceremonial nor fair.

Enslaved men and women fought with years’ worth of grief and clarity.

The Order discovered that prestige does not armor flesh.

Harrison saw William in the orange light.

“I’m your father.”

“You ended that,” William said, and shot him low.

Harrison folded around the wound, bleeding into the earth he believed he owned.

They unchained Mercy.

Her wrists were raw, her voice steady.

“We leave,” Samuel said.

“Now.”

They fled through the root cellar tunnel into the fields.

Peton House roared as if the flames were hungry for secrets.

By dawn, timber lay charred, a skeleton collapsed into ash.

Seventeen bodies were counted in the cellar.

The official story named a lamp and a business meeting.

The county did not examine too closely.

Power prefers accidents when truth convicts.

Flight and the Long Road

Mercy and William moved north that night with fifteen others, trading silence for speed, stopping at safe houses where hands gave bread and directions.

The Underground Railroad stitched their fear into progress.

They reached Philadelphia, where the Pennsylvania Abolition Society gave them names to live under and work that built dignity instead of wealth for others.

Mercy became a midwife and healer.

Her reputation grew, not because she was loud, but because babies breathed and fevers broke.

She never married.

Grace remained the measure of her heart.

William taught children their letters and their histories without the lies that had deformed his own.

He never married.

He did not ask for absolution.

He carried the weight like a ledger from which he would never erase his name.

The haunting softened but did not stop.

A child at the periphery, watching.

A reminder he deserved.

They remained bound by survival and by a truth that institutions refused: sometimes justice rises from the people who have been forced to bleed for everyone else.

The Ledger Speaks

In 1857, a package arrived at the Boston offices of The Liberator.

Inside was a dossier detailing the Order of the Crimson Crown: names, dates, rituals, diagrams of the Peton House cellar, minutes written in the careful hand of someone who learned to write in corners and saw everything.

The newspaper published installments.

North Carolina stiffened under public scrutiny.

Many of the named men were already dead; the revelation still tore at the fabric that had shielded them.

No author’s name appeared.

The handwriting was split: half Mercy’s elegant script, half William’s steadier lines.

Together they ensured that Peton House was not only ash but record, that Grace’s name did not vanish under dirt, that forty-three other victims became something more than rumor.

Bowfort County learned that power is a scaffolding, not a law of nature.

The story traveled.

It became one more tension pulling the country toward war.

It exposed what wealth was willing to do to stay whole.

It proved that the powerless were not without weapons.

Afterword: Weight and Witness

There were witnesses who ran from William’s changing body in fear—physicians who examined him and saw a transformation that defied their practice and their pride.

They saw a man who lost more than pounds.

They watched him erode and reform into someone capable of choosing against blood.

Nine men died under circumstances no court tried to explain honestly.

Peton House burned not only with flame but with the sudden clarity that systems collapse when enough people refuse their terms.

The disturbing truth of what happened between Mercy and William does not rest in appetites or in nightmares alone.

It lives in the moment Mercy said no.

It lives in the hours she built a routine that dismantled years of excess and opened a mind to memory.

It lives in a ledger read by hands that had held newborns and graves, and in a fire that unmasked ritual as murder.

Grace remained.

Mercy remained.

William remained, altered and accountable, a man who understood too late what life asks of those it harms.

The county moved on.

History tried to bury what was inconvenient.

But stories like this persist, because some things refuse to be swallowed.

They thought the enslaved could not think.

That was their fatal mistake.

News

She Was ‘Unmarriageable’—Her Father Gave Her to the Intelligent and Talented Slave, Virginia 1856

I was seventeen courtships into humiliation by the time my father made his most audacious decision. In Charleston parlors, they…

(1865, Sarah Brown) The Black girl with a photographic memory — she had a difficult life

In the spring of 1865, as the war sputtered toward surrender and lawmakers hammered freedom into the Constitution, a seven-year-old…

The millionaire master bought an enslaved woman for his son — what she did next no one ever forgot

Charleston woke humid and heavy, the kind of morning that stuck to skin and wouldn’t let go. Esther stood on…

Gideon Marshall the wisest slave in New Orleans, who deceived and destroyed seven plantation masters

There are stories that history tries to bury—too dangerous to tell, too unsettling to admit. They whisper a truth that…

Slave Finds the Master’s Wife Injured in the Woods — What Happened Next Changed Everything

The scream was so faint it could have been a fox, or a branch torn by wind. Solomon froze on…

The farmer promised his daughter to a slave if he planted 100,000 corn in 2 months—no one believed.

The summer heat in Franklin County, Georgia, did not simply sit on a man; it pushed. It pressed against lungs…

End of content

No more pages to load