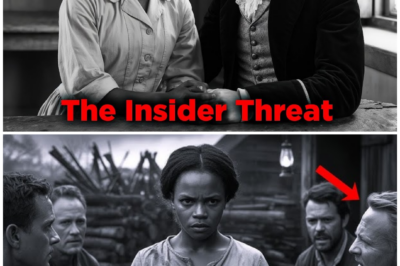

They found the master’s body at dawn, face down in the lily pond, his pockets full of stones.

What troubled the house servants most wasn’t the death itself.

It was the way Mistress Catherine stood at her bedroom window as they dragged him out, one hand resting on her swollen belly, lips curved into something too heavy to be called a smile.

The baby kicked.

I know because I stood behind her, close enough to see her silk dressing gown ripple.

She slid her other hand over mine where it rested on the sill and whispered, soft as rot, “It’s done now, Samuel.

Everything I promised you.”

The summer of 1855 arrived at Thornwood Plantation like a fever.

The air shimmered over the cotton fields, and men’s thoughts turned strange.

I’d been at Thornwood seven years, purchased at a Charleston auction when I was nineteen, worth set by the width of my shoulders and the straightness of my spine.

Master Richard Thornwood paid a premium and made a show of getting his money’s worth.

He worked me harder than most, but tempered his cruelty with the crispness of a man who liked his accounts balanced.

It was a distinction without a difference.

A gilded cage is still a cage.

Mistress Catherine was twenty-four that summer, nine years younger than Richard.

She had pale skin that never tanned and eyes the color of pond water after a storm—murky, unsettled, hiding whatever lived beneath.

She had been married six years and had produced no son.

In our corner of the world, a woman without an heir turned from bride to burden.

Richard had begun to look across the dinner table with disappointment aged into contempt.

I served their meals and saw it settle on her like dust.

The first time Catherine spoke to me, I was repairing fence along the garden path, shirt soaked through with sweat, hands raw from wood.

She approached with a parasol and a circle of shade delicate as lace.

“You’re Samuel, aren’t you?” Her voice came honeyed from Charleston, but something hungry pulsed beneath.

“Yes, mistress,” I said, eyes on the fence post.

“My husband says you’re the strongest man on the plantation.” She tilted the parasol.

I felt her gaze travel.

“He’s right, isn’t he? You are strong.”

There was no safe answer.

“Strong enough to do my work.”

“Strong enough for many things, I imagine,” she murmured, turning away.

Her skirts rustled like a secret.

After that, she found reasons to appear wherever I worked—stables, garden, the far fields—crafting conversations long enough to be improper, not long enough to be scandalous.

She asked about my life before Thornwood, the family sold away when I was twelve, my thoughts on crops and quarters.

Her interest wasn’t kindness.

It was calculation.

Richard’s temper soured with the heat.

I heard him rage through the walls.

Barren, he’d spit.

What good are you? Catherine’s voice turned cold as bone.

Perhaps the fault lies not with the soil but with the seed, she would say.

He began spending evenings in town, drinking and gambling his father’s order into disrepair.

We felt the change like a barometer needle.

Something was coming, and we were trained to know it before it arrived.

Late in July she came to my cabin after midnight.

Her hand covered my mouth, face pale in moonlight, breath quick.

“Don’t speak,” she whispered.

She wore a simple dress, hair unbound.

She sat on the edge of my bed with impossible composure.

Every instinct in me recoiled, but instincts are nothing against law.

“I need your help,” she said.

“I need you to give me a child.”

The words hung like smoke.

To refuse was death.

To comply was the same.

“Mistress—”

“Richard is infertile,” she said flatly.

“I consulted physicians in Charleston.

Childhood fever left him unable to father children.

He will never admit it.

He will cast me aside.” Her eyes glittered.

“This life is mine by right of marriage.

I will keep it.

To keep it, I need an heir.”

She’d thought through everything.

My mother’s mother had been half-white, the ledger recorded it.

“You’re hardly darker than some Italians,” she said.

“I am fair, Richard is fair.

People see what they expect to see.”

“And me?” I asked.

“What happens to me in your plan?”

“You will be protected.

Better food, lighter work,” she said.

“As long as you are loyal.”

“I want freedom,” I said, surprising myself with the truth.

Her voice hardened.

“Freedom isn’t mine to give.

But I can make captivity bearable.

Or I can make it unbearable.

There is no third option.”

There are horrors that do not need excavation.

She came in darkness, left before dawn, returned two nights later and again, turning the unthinkable into ritual.

She spoke only to instruct.

I went away inside myself and stayed there until morning.

Six weeks later she announced at breakfast—loud enough for the house servants’ ears and tongues—that she might be with child.

Richard transformed at once, a man resurrected.

He brought her gifts, canceled his nights in town, played the expectant father with a zeal that felt like denial made flesh.

Catherine stopped visiting my cabin.

I told myself I felt relief.

I lied to myself as easily as I lied to everyone else.

In October, with the air finally cool, Richard called me to his study.

He stood at the window with whiskey in hand.

“Samuel, you’ve been with us seven years,” he said.

“You’re valuable.

Mitchell downriver has offered me twice what I paid for you.” He turned, troubled.

“We’ve had…difficulties.

Your sale would ease things.

However—” His mouth twisted.

“My wife objects.

She says you’re essential.

She was…emotional.” He studied me.

“Tell me, Samuel, why would my wife care so much about keeping you here?”

There was a silence sharp enough to cut.

“Perhaps because I know the property well, master,” I said.

“Or perhaps there’s something else,” he said quietly.

He released me with a warning: he would be watching.

The winter turned the fields iron-gray.

Richard’s mother, Constance, arrived—steel-gray hair, eyes like ice, displeased with everything she saw.

Within an hour, she had seized the household reins with military precision.

I trimmed hedges beneath the parlor window and heard them spar.

“You look well,” Constance said, “but something about you troubles me.”

“Don’t we all harbor secrets?” Catherine’s voice cool and controlled.

“It’s what makes us dangerous,” Constance said.

“I’ve made inquiries.

Your visits to Charleston physicians—”

“What business is that of yours?”

“This child is Thornwood business,” Constance said.

“If there’s any question of paternity—”

“How dare you,” Catherine snapped.

“I suggest nothing.

I observe that your sudden fertility aligns with the arrival of certain robust specimens,” Constance drawled.

“That field hand, Samuel.

Strange, isn’t it, how you blocked every attempt to sell him?”

“He is valuable,” Catherine said.

“He is something,” Constance said.

Silence stretched.

“Truth reveals itself.

Blood will tell.

When the baby arrives, it will speak its own story.”

That night Catherine came to my cabin, haggard and unmasked.

“She suspects,” she said.

“She means to destroy me.

I won’t allow it.

I will eliminate any evidence that suggests otherwise.”

“Me,” I said.

“Not yet,” she murmured.

“After the child is born.

After enough time has passed.

Then we’ll see.”

I should have run.

I did not.

Perhaps it was cowardice.

Perhaps I needed to see what became of the child who carried my blood.

Or perhaps I was already ensnared by the dark pride of being chosen for something no man should be chosen for.

The baby came with the frost, on a February morning brittle as glass.

Catherine screamed for twelve hours while I hauled wood until my arms sang with pain, because doing something was the only thing that kept me from falling apart.

After midnight the midwife emerged, smiling.

“A boy,” she told Richard.

“Healthy.

Your heir.”

Richard made a cracked sound.

“And he’s…?”

“Perfect,” she said.

“Strong lungs.

Some color to him.

The mistress says there’s Italian blood.

That would explain it.”

I walked into the frozen fields and kept walking until the house was a smudge, until the newborn’s cry no longer pressed at my ribs.

The child was mine in blood and nothing else.

He would never know me.

He was baptized John Richard Thornwood.

Neighbors cooed at his olive skin and dark hair, eager to accept Catherine’s talk of Mediterranean ancestors.

People see what they want rather than what is.

Constance held the child and examined him as if he were a fine porcelain with a hairline crack.

“He has your eyes,” she said to Catherine, loud enough for others to hear.

“Though the rest—” She left the rest hanging like a blade.

Catherine’s hands trembled.

She was terrified, I realized.

The lie demanded constant performance.

Even a perfect performance wears a woman to nothing.

Spring brought an uneasy calm.

Catherine became a mother with ferocious precision, nursing John herself to keep him near, as if proximity could make him more hers.

Richard doted, muttering about the future and legacy, his drinking easing in a brief reprieve.

But truth has weight.

It presses through walls and under doors.

Catherine’s gaze found me whenever I came near the house.

Richard began to watch both of us.

The air thickened again.

In May, he called me to his study.

A pistol lay on the desk.

“Tell me the truth,” he said.

“About my wife.

About my son.”

“Master, I can’t tell you anything that will bring peace,” I said.

“Only that I never chose any of it.”

“Did she force you?” he asked.

“Does it matter?”

“It matters to me,” he said hoarsely.

“She came to my cabin,” I said.

“She planned everything.”

He closed his eyes.

When he opened them, grief and rage and humiliation flickered and then went numb.

“She used us both,” he said.

“I should kill you.” His hand hovered over the pistol.

“Get out of my sight, Samuel.

Pray I don’t change my mind.”

I went straight from his study to the nursery.

Catherine looked up from the rocker.

“He knows,” I said.

She stood abruptly, clutching John.

“He’ll keep the secret,” she said, too quickly.

“He’s proud.

He won’t destroy himself to punish me.” Her voice wavered.

“Constance knows too.”

“She suspects,” Catherine spat.

“She has waited for my failure since the day I arrived.

But suspicion is not proof, and Richard won’t give her satisfaction.”

I asked, “What happens to me?”

“You will stay.

You will work.

You will never speak of this again.”

“What choice do I have?”

“None,” she said simply.

The drought came with the summer of 1856, shrink-wrapping everything—streams, tempers, judgment.

Richard’s drinking returned with vengeance.

He and Catherine tore each other to pieces with words in rooms I hovered outside because it was my job to be near.

One afternoon, heat hard as a fist, his rage spilled into the yard.

“You,” he hissed, slamming me against the stable wall.

“You burned my life to ash.” I said nothing because there was nothing to say that wouldn’t stoke the fire.

“I should kill you,” he muttered, stumbling away.

“I should burn this whole place to the ground.”

Two weeks later, on a cooled night, he filled his pockets with stones and walked into the lily pond.

They called it an accident at dawn.

We called it what it was in the silence between us.

Catherine watched from the window and told me everything she planned to tell herself.

“It’s done now,” she said.

“Everything I promised you.”

I pulled my hand from hers.

“You said he would keep quiet.”

“He would have told eventually,” she said calmly, eyes still on the men in the mud.

“I couldn’t allow that.

John will inherit.

No one can contest it now.”

“You murdered your husband.”

“I freed him from misery and freed us from exposure,” she said, turning toward me with eyes emptied of all but purpose.

“You and I are bound now.

We created life.

We did what we had to do.”

“I can’t,” I said.

“Not after this.”

“You can and you will,” she whispered.

“Or I tell the authorities you forced yourself on me and murdered him.

Who do you think they will believe?” She was right.

Even my rage had to kneel to power.

She came to my cabin again, at night, afterward.

The encounters turned dark, turned punishing—for me, for her, I couldn’t tell.

I stopped thinking of myself as human and started moving through days as if my body were a tool left out in the weather too long.

Constance arrived for the funeral and pulled me aside in the garden.

“I know what you are and what she made you do,” she said in a voice scraped down to its truth.

“I could expose it.

I won’t.

That boy is innocent.

Richard loved him.

Let him keep that.” She paused.

“But watch yourself.

She’s a spider.

When mates become liabilities, spiders eat them.”

The months after settled into a terrible order.

Catherine modernized operations with efficient cruelty.

Profits rose.

At night she called me into Richard’s old bedroom to prove some point only she understood.

John grew bright and beautiful, his eyes solemn and curious.

He would wander to the garden to watch me work.

“Why are you sad?” he asked once, three years old, hands clasped behind his back like his mother.

“I’m not sad, young master.”

“Yes, you are,” he said, seeing more than any man had.

“Mama says you’re the strongest.

Do you have children?”

The question struck like a hammer.

“No.”

“That’s sad,” he said.

“Everyone should have children.

That’s what Papa William says.”

Catherine remarried in the spring of 1858 to William Mercer, a practical neighbor whose interest lay in yields, not romance.

He treated Catherine with courteous distance and John with paternal affection.

From the road, it looked like stability.

Catherine kept me, too—summoning me to abandoned cabins, the stable loft, the far corners of fields.

The risk thrilled her.

It sickened me.

My resolve to run hardened.

I planned for two weeks, stashing food, tracing roads, learning whispers of routes to the North.

On the eve of my escape, William called me to his study.

Catherine sat by the window, pale and still.

“There have been suggestions,” William said, voice thick with embarrassment.

“Improper relations between my wife and a member of the enslaved workforce.

You.” He looked at me.

“Have you ever had improper contact with my wife?”

I looked at Catherine.

Her expression held the warning like a blade.

Deny it or die.

“No, sir,” I said.

He studied me for a long time, then dismissed me with a promise to watch.

The net tightened.

That night Catherine came to my cabin.

“We have to stop,” she said.

“For now.

Constance is set on destroying me.

William is wary.

We will wait until it blows over.”

“It won’t,” I said.

“Truth wants out.”

“We will keep it down,” she said fiercely.

“I won’t lose everything.

Not now.”

“Stay away from me,” I said.

“For both our sakes.”

“Fine,” she said after a long look.

“But if they come for me, I won’t go down alone.

I’ll take you with me.

We are bound together.”

For six months she stayed away.

Constance circled like a vulture that refused to land.

William grew quiet and watchful.

In February 1859, Catherine announced she was pregnant again.

This child would be William’s, undeniable.

She summoned me to the house with witnesses and announced my sale to a plantation in Alabama, leaving in a week.

Alabama placed a continent between me and my son.

It also cut the last strands of a web that would have strangled me.

That night Catherine came to my cabin one last time.

“You’ll be treated well,” she said.

“Overseer’s work.”

“Blood money,” I said.

“Life,” she said.

Then, softer, “I’m sorry.

I thought we could build something from wreckage.

We can’t.

Survive separately.

That’s the best we can do.”

“What about John?”

“He’ll be fine.

He’ll grow up believing what he needs to believe.

Isn’t that what you want?”

“I want him to know the truth.”

“The truth would destroy him,” she said.

“Some truths are too dangerous to speak.” At the door she turned.

“You may say goodbye tomorrow.

Five minutes.”

They brought John to the garden.

Catherine stood at a distance, guard and witness.

John came to me with his solemn curiosity.

“Mama says you’re going away,” he said.

“Yes.”

“Will you come back?”

“I don’t think so.”

“That’s sad,” he said, considering.

“I’ll miss you.

You’re nice to me.”

I knelt so we matched in height.

“Young Master John, you’ll become a man.

You’ll make choices about what kind of man to be.

Those choices matter.

Promise me you’ll remember people are people.

All of them.”

“I promise,” he said with the unearned ease of a child.

I did something I’d never dared.

I pulled him into a hug, breathed him in, and let go.

Three days later, chained with four others, I left Thornwood.

The Alabama plantation was, as promised, marginally better: small privileges in exchange for being the lashes’ extended hand.

I moved through those years like a ghost, listening for shreds of news carried along the clandestine wires of human mouths.

I learned Catherine bore a daughter, William’s child.

I learned John thrived.

Then the war came like judgment.

When freedom reached us in 1865, I did not feel joy.

I felt untethered.

After twenty-three years, liberty was a country without a language I knew.

I went back to South Carolina.

Thornwood was a charred shell.

The fields were wild.

Catherine died in 1864 of pneumonia.

William fell at Gettysburg.

Their daughter died of fever.

John survived.

He had been too young to fight.

I heard that after emancipation he offered wages instead of chains, divided land, tried to act justly in a place with no memory for justice.

I traced him to Charleston, a clerk in a law office, inheritance gone, pretensions shed.

I stood across the street and watched him through a window—twenty, serious, carrying weight beyond his years.

He looked like me.

He looked like her.

I returned for several days, watching him treat Black workers with ordinary respect uncommon for the time.

I told myself I needed to know what kind of man he was before I broke his world.

The truth was I was afraid.

In the market one afternoon, three drunk veterans cornered a Black woman, accusing her of theft.

John stepped between, firm and calm.

“Leave her alone,” he said.

They turned on him, calling him a traitor.

I stepped beside him before I knew I’d moved.

Others drifted closer.

The men cursed and stepped back.

John turned to me, flushed.

“Thank you,” he said.

“They weren’t listening to reason.”

“Reason wasn’t what they wanted,” I said, taking him in up close: the lines of his face, the weight in his eyes.

“Have we met?” he asked.

“Perhaps long ago.”

He offered his hand.

“I’m John Thornwood.

Well—John Mercer Thornwood.

Mostly just Thornwood.”

“Samuel,” I said.

“Just Samuel.”

We spoke for an hour and then again on other days, a friendship growing in the easy soil of shared purpose.

He spoke about his childhood, vague memories of gardens and a kind hand somewhere in them, his mother’s iron, his stepfather’s steadiness.

He spoke about the war, the crumbling of belief.

He wanted to use law to help the newly freed navigate a world designed to refuse them.

I listened and asked and learned.

I never told him.

If you’re waiting for revelation, there is none here.

Telling him would have satisfied me and shattered him.

It would have turned his mother into a villain and me into a man he would be forced to mourn anew.

It would have shifted the ground under every step he took.

Sometimes love is a weight you carry alone so others don’t have to.

I stayed in Charleston five years, watched him marry a kind woman, watched him build the family he’d never had.

I left for Philadelphia and made a quiet life.

I did not marry.

I did not have more children.

My son was enough.

In 1889, a law firm’s letter found me.

John Mercer Thornwood had died of heart failure at forty-four.

I was mentioned in his will.

A small bequest.

A sealed letter to be opened only by me.

I sat in a hotel room with his letter and read:

Samuel,

If you’re reading this, I’m gone.

I never had the courage to speak while I lived.

I’ve known for twenty years.

Did you think I didn’t recognize you when you appeared in Charleston? Did you think I couldn’t add dates together? Couldn’t remember the way my mother looked at you in my earliest memories? Couldn’t understand why a man of your age and intelligence remained unattached, always watching me from a careful distance?

I figured it out slowly—conversations with former Thornwood slaves, old records, memories that made sense in context.

When I understood who you were and why you stayed silent, my heart broke for you.

I also understood why you said nothing.

You thought you were protecting me from the knowledge that my mother was a murderer, that my father was a man she exploited, that my life was built on lies.

Maybe you were right then.

Maybe as a young man I would have been crushed.

But I wish you had told me.

I wish I could have called you father.

Knowing the truth didn’t destroy me.

It changed me.

It made me more determined to fight the system that made our relationship impossible.

It did not make me love you less.

It made me love you more—for your strength, your grace, your kindness in letting me live in ignorance.

I never confronted you because I respected your choice.

But I want you to know I saw you.

I knew you.

I tried to honor you by becoming the kind of man you’d be proud of.

I’m leaving you a small legacy—not as payment, which would be an insult—but as acknowledgment.

You matter.

Your suffering was not invisible.

Thank you for the garden conversation when I was four.

Thank you for the promise you asked me to make.

I’ve tried to keep it.

With gratitude and love,

Your son, John

I wept in that room—racking, unguarded sobs of a man who had been silent too long.

My son had known.

He had carried the truth quietly beside me for two decades.

He had loved me anyway.

He had honored my silence with his own and built a life that turned inherited guilt into active redemption.

Catherine died believing she had won, believing her design would stand.

In a way, she did build something, just not what she thought.

She built a son who rejected the foundations of her survival.

She wanted an heir to perpetuate a system.

She got one who helped dismantle it.

Is that justice? Justice is a word too clean for the labyrinth we walked.

But it is something.

A rebalancing in a universe that rarely balances itself.

I am ninety-one now, writing this in 1927, sixty-two years after freedom and seventy-two after Catherine first stopped at a fence line and ruined and remade my life.

I write because John asked me to tell the truth, when it could be history instead of scandal.

The truth is complicated: Catherine was a murderer and a manipulator, but also a woman trapped by a world that called her worthless without sons.

Richard was weak, but he loved a child he believed was his.

I was enslaved and violated; I was also complicit, a victim and a collaborator.

I carried an unbearable weight as gracefully as I could and made choices I’m still not sure were right.

I let my son grow up without knowing me.

I will never know if that was protection or cowardice.

I do know this: John was worth it.

He existed because of everything I endured.

He became better than all of us.

He took darkness and, particle by particle, turned it into light.

That is not the ending Catherine planned.

It is the ending we got.

In a broken world, it may be the closest thing to victory anyone can hope for.

News

The Widow Who Made Her Three Sons Swear To Share One Slave Wife—The Night Their Oath Broke, 1846

The swamp light turned everything the color of old paper the first Sunday evening I saw the three graves. They…

Slave Girl Seduced the Governor’s Son — And Made Him Destroy His Father’s Entire Estate

The seduction, they would later say, began in the chandeliered light of a ballroom. But Amara knew it started years…

She Was ‘Unmarriageable’—Her Father Gave Her to the Strongest Slave, North Carolina 1855

The night my father bargained my life away to the man everyone on our plantation called Goliath, the lamplight caught…

A lonely man from Mississippi bought 3 virgin slave girls – what he did with them shocked everyone

The iron bell of the auction house clanged through the humid air of Natchez, Mississippi, on a blistering July afternoon…

The Profane Secret of the Banker’s Wife: Every Night She Retired With 2 Slaves to the Carriage House

In a river city where money is inked but paid in human lives, the banker’s wife lights a different fire…

The Plantation Lady Who Locked Her Husband with the Slaves — The Revenge That Ended the Carters

The night I decided my husband would go to sleep on a slave’s pallet, the air over Carter Plantation felt…

End of content

No more pages to load