The night I decided my husband would go to sleep on a slave’s pallet, the air over Carter Plantation felt like wet wool pressed over a drowning mouth.

Cicadas screamed as if someone were pinching them one by one.

Out beyond the veranda, the quarters lay low and uneven, roofs sagging, chimneys coughing thin smoke into humidity.

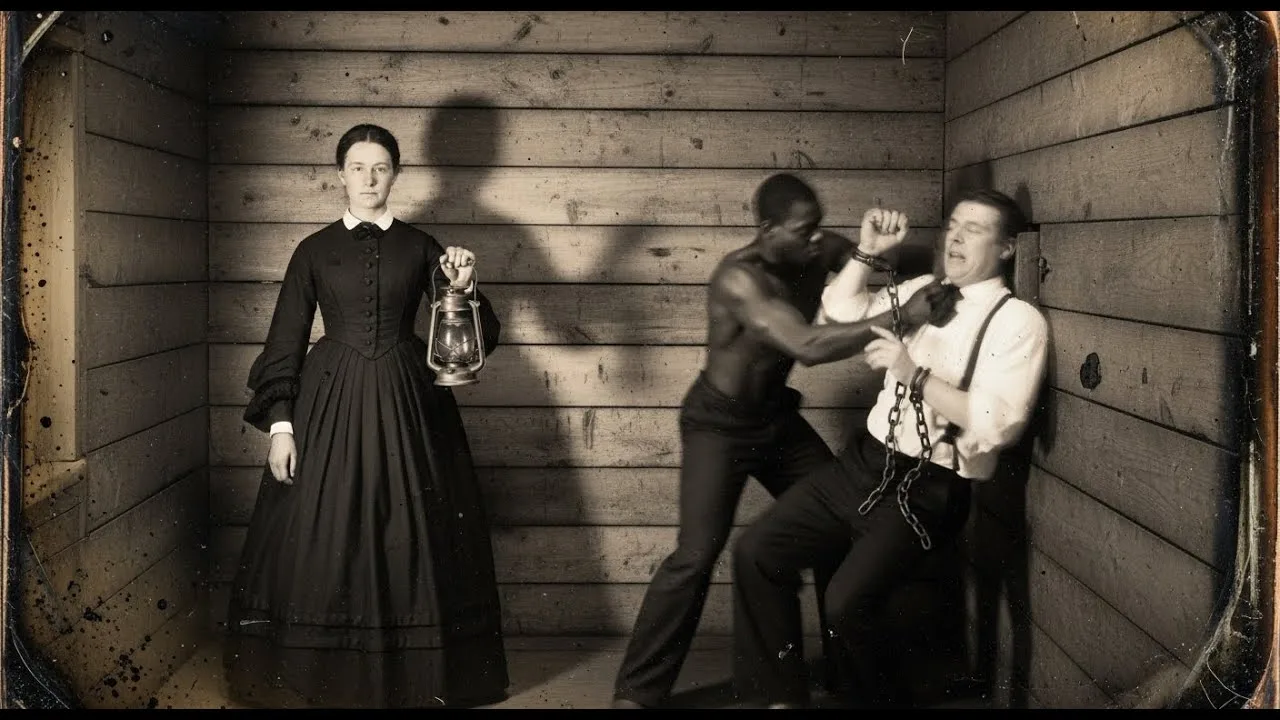

A lantern swung from my hand; its light shivered over packed earth.

In my pocket, the iron key thudded cold against my thigh with every step.

I had walked this path a thousand times as Mrs.

Thomas Carter—mistress of the house, dispenser of scraps and orders, and carefully measured kindness.

This was the first time I walked it with murder—or something close—standing patiently at my side.

“Evening, Mrs.

Carter,” Isaiah said at the edge of the first shack.

He stood nearly as tall as the doorway, shoulders heavy with labor, shirt stuck to his back.

Lantern light caught old rope scars at his wrists, white ridges cutting through dark skin.

His eyes, when they lifted to mine, were steady and too clear for a man who’d lived this long under Thomas’s hand.

“Is it ready?” I asked.

He glanced toward the back of the row, where one shack sat apart, built of thicker boards with iron rings sunk into its walls.

The punishment shed—Thomas’s school for lessons that lasted longer than bruises.

“Yes, ma’am,” Isaiah said.

“Everything’s like we talked.

Rope, chain, water—just enough.

He won’t get out.” He spoke about my husband like a wild hog caught at last in a pit.

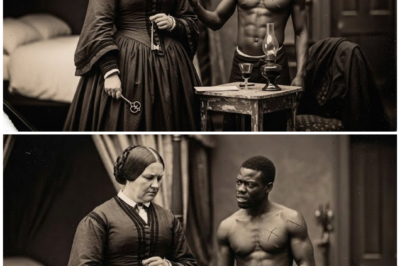

For most of my married life, Thomas kept all the keys that mattered—to the cashbox, gun cabinet, and the papers that said what was his and, by law, what was mine—but never truly mine.

He jingled them when he paced.

Let them chime when he said certain rooms were not for ladies, certain matters too tender for their minds.

Now the heaviest key was in my dress, and Thomas didn’t know his own locks had betrayed him.

“We’ll start from the beginning,” I said.

“He must believe there’s been talk of a rising.”

Isaiah’s jaw flexed.

“He already believes it, ma’am.

Men like him walk around with ghosts at their heels.

They know what they’ve done.”

Ruth stepped from a doorway’s shadow, wiping her hands on her apron.

She’d been in my house eleven years, carrying trays and secrets with equal care.

“The others are ready,” she said quietly.

“They know the plan—or the part they need to know.”

“The part that says don’t kill him,” Isaiah added.

“Hardest part for some to understand.”

I looked down the rough row and saw other nights: Thomas’s voice in the yard, loud and amused; the wet slap of leather; a boy’s scream cut short like someone had shut a door on it.

I saw the day a teenage girl with eyes older than mine stood in my doorway, arms around a baby with Thomas’s eyes, begging me not to let him be sold away—and me, a good southern wife, frozen between truth and the lie I’d been raised to embody.

The plan was not born in a single moment.

It layered season over season like soot on chimney bricks.

If there was a night it took form, it was when Thomas made me watch the boy’s whipping.

Iron in the air.

Magnolia rotting sweet at the yard’s edge.

Thomas’s hand heavy on my elbow.

“You ought to see what mercy looks like,” he said, smile thin and righteous.

The boy, maybe fourteen, wrists like twigs, accused of stealing rope.

Bound to the post, shirt stripped, back trembling.

An overseer held a whip; another held the crumpled rope.

“I don’t—” I began.

“Slaves ought to see you stand with me,” Thomas cut in.

“Neighbors whisper you’re too soft.

Let them be wrong.”

The first strike landed.

The sound was nothing like whip on leather.

Wet.

Ugly.

Wrong.

The boy’s noise was somewhere between sob and howl.

A picture frame tipped inside me.

By the third blow, my eyes burned.

By the seventh, I stopped counting.

“Spare the rod, spoil the slave,” Thomas narrated like scripture.

“Children.

Beasts.

Pain has purpose.

You understand, Evie?”

I nodded—or something like it—because refusal had no safe shape.

Later, alone in my dressing room, I stared at myself by candlelight and saw not a lady, not a wife, but an accomplice.

Rage came up cold and slow like swamp water seeping through floorboards.

A week later I walked where Thomas rarely looked—behind the wash house, past the smokehouse, out toward the low shacks.

Isaiah was a man sitting with his back against a tree, face turned up to the narrow slice of sky.

Fresh lash marks scabbed his cheeks where punishment had kissed him another day.

“Mrs.

Carter,” he said, without surprise.

“You’re off your proper path.”

“Perhaps my proper path is what I’m trying to find,” I answered.

We talked cautious words at first.

Later Ruth talked too—breadcrumbs dropped in my path: how Gideon Hail spoke of Thomas behind his back, how debts shifted, how Thomas had more enemies than friends at the county seat.

Then came the argument in the study.

Gideon oily with concern; Thomas harsh with anger.

“You can’t keep them all,” Gideon said.

“Especially not that woman and her brats.

Folk are noticing.

Some of those children got your height.

Your eyes.”

“I don’t care what they notice,” Thomas snapped.

“If they don’t like it, they can buy their own breeding stock.”

Glass shattered.

Heavy footsteps paced.

“You sell that woman,” Gideon insisted.

“You sell the boy too.

Clean the slate.”

My fingers tore wallpaper vines and flowers across plaster like ruptured veins.

“He means Mariah,” Ruth said in my doorway.

“And her boy, the one with the gray eyes.”

The boy with his eyes.

She nodded.

“He’s done it before.

He’ll do it again.”

Fear of consequences.

That was what I decided to give him.

Thomas trusted punishments more than locks.

When he feared unrest, he chained men in that shed so they couldn’t stand upright, believed hunger taught, darkness tutored.

It seemed right he should be tutored by his own methods.

By the time I came down the moonless path with the lantern and the key, the ground had been tilled long.

“You understand?” I said to Isaiah.

“He does not die quickly.

If he dies, it will be the last piece, not the first.”

Isaiah’s eyes held the earlier echo: You want him to live like us before he dies like us.

“Yes, ma’am.

We keep him breathing a while.”

Ruth nodded.

“Food gone thin.

Water counted.

No one touches him unless it’s needed for the visits.”

Visits.

Mine.

If Thomas’s soul had its flesh peeled back, it would be by words—forcing him to hear what he’d shut his ears to for years.

“Then all that remains is to deliver him to his room,” I said.

Back at the big house, lamps burned.

Gideon Hail’s carriage waited.

He had wiped gravy with my linen while he and Thomas spoke of cotton and abolitionist pamphlets up north.

“I did overhear something curious,” I said, letting my voice tremble.

“Two of the field hands—songs… night songs… codes.”

Men like my husband believed women lived in fog.

Plant a hint of knowledge, and pride would drive action.

“Songs?” he repeated.

“Who?”

“I don’t know their names,” I lied.

“They were near the punishment shed.”

“I’ll handle it,” he snapped, rising.

Theater of authority delighted him—especially with audience.

“Stay inside, Evie,” he ordered, checking his pistol.

“This is men’s work.”

I watched from the window as he strode into dark, lantern light pooling around his boots.

Two overseers followed.

“They’re almost there,” Isaiah whispered now in the present.

We watched lanterns bob and heard Thomas bark: “Up! I hear talk of codes, rebellions.

Any of you feel like dying tonight?”

Ruth blended with shadows, nudging some forward, yanking others back.

Truth was scattered so thoroughly even the innocent wouldn’t be sure.

Fear entered Thomas’s tone when he realized one overseer was missing.

“Where’d Carson go? He was right behind me.”

A raw-throated cry from behind the shed.

Carson under strict instruction to sound hurt.

Thomas stomped toward sound.

“You stay,” he barked at the cluster.

“Anyone moves, they get twenty.

Hear me?”

Ruth hissed, “Back inside.” They melted, speed born of centuries of knowing when not to see.

A minute later the yard was empty save for me, Ruth, and cooling puddles of light.

Isaiah emerged, breathing hard, shirt torn.

Blood speckled his knuckles.

“It’s done.

He’s in.”

I rounded the corner.

Inside, lantern light picked out rusted iron rings, dirt floor, low ceiling.

Thomas sprawled, furious, wrists chained overhead so his arms were stretched and bent—no standing straight, no hanging.

A gag of torn cloth stuffed his mouth, tied tight.

His pistol lay kicked out of reach.

He rattled iron when he saw me, face flushed mottled red.

The sound he made was half growl, half plea.

“Evening, husband,” I said.

Ruth stood behind me.

Isaiah blocked the only other exit.

Thomas choked around the gag, eyes bulging at Isaiah—still expecting a narrative he understood: a slave revolt with me as hostage.

He could not imagine that a slave’s hatred might be patient.

I drew out the key.

Confusion crossed his face.

“Do you remember the boy with the rope?” I asked.

He made another sound.

“You chained him here.

Left him three days.

No water first day, no food second.

Every time he slumped, his wrists took the weight.” Lantern light caressed the iron above his head—rust streaked where old blood had browned.

“I listened to him cry at night.

You slept well.”

Pain cut through his anger.

“This is what happens now,” I said.

“You live in here.

You eat when fed.

You drink the water brought.

You do not command.

You do not whip.

You learn the world when you are not at its center.”

He tried to shout.

Isaiah stepped forward just enough to let Thomas see rope marks healed into his wrists.

“Looks like we’re trading places,” he said.

Thomas threw himself forward, chains clanged; vein stood out in his neck.

For a moment I thought he might crack his skull against iron.

“Oh no,” I murmured.

“You don’t get that way out.

You stay alive.”

“Make sure he has water,” I told Ruth and Isaiah.

“Not too much.

Enough to keep his mind awake.”

As we left, his muffled shouting followed us into night.

Something loosened in my chest—not joy, which needs light and space, but a bone set after too long broken.

For a few days, Thomas was noise.

He screamed until his throat went ragged.

He lunged at bowls like a starving dog—fury, not hunger.

“Don’t let him starve,” I reminded.

“He mustn’t die yet.”

“You sure you ain’t building him into some martyr?” Isaiah asked.

“Some men need killing quiet, not punishing loud.”

“He has no soul to martyr,” I said.

“But he has a name.

I intend that name to end with him.”

On the fourth day, I brought the first story.

We had allowed his gag removed that morning; Isaiah stood within arm’s reach, chain in hand.

“What is this?” Thomas rasped.

“Evelyn—what in God’s name—”

“Careful invoking God,” I said.

“You beat people in His name often enough.

Best not call witnesses you cannot impress.”

“You’ve lost your mind.”

“Perhaps,” I agreed.

“But I found something else.”

Ruth guided in a small figure.

He was nine or ten, thin as a fence post, eyes pale gray—my mirror’s ghost.

He clutched his cap, knuckles white.

“This is Jacob,” I said.

“Say hello to your father.”

Thomas froze.

The boy looked from me to him and back, hungry confusion in his face.

“I don’t—” Thomas began—then saw his own cheekbones, mouth, eyes.

“You’re making this up,” he muttered.

“I don’t know this boy.”

“You knew his mother well enough,” I said.

“Mariah.

You tried to sell them both when Gideon suggested it, but the papers got delayed.

Some of us delay things on purpose.”

“I— I gave them work.

Food—”

“You forced yourself on his mother,” I cut in sharply.

“Repeatedly.

You called it taking what’s yours.

She called it surviving because you had a whip and a bill of sale.”

Jacob flinched at the ranker without grasping the full meaning.

“Tell him what you told me,” I said gently to Jacob.

He licked his lips.

“I heard Ma crying,” he whispered.

“And you yelling, sir.

I was in the corner.

She told me not to move.

Said if I made a sound, she’d be in trouble.

You said I wasn’t your problem.

You said you’d sell me if she didn’t stop crying.”

Thomas’s mouth worked without sound.

“You threatened a child to keep a woman quiet,” I said.

“This is the harvest, Thomas.”

We did not stay long.

It wasn’t safe to expose the boy to his father in this state.

But long enough for the story to seep into the cracks of denial.

More stories came.

A former overseer with a limp spoke of being ordered to break Isaiah’s ribs—and docked pay when he hesitated.

A woman with a twisted hand recounted the night her sister hanged herself in the wash house after Thomas “favored” her one too many times.

An old man, nearly blind, told of a son sold south for daring to look Thomas in the eye.

Each time I sat on an upturned crate, hands folded, listening as much as forcing him to listen.

Each time I watched him shrink—a dent here, a dent there in the armor of righteousness.

“Sometimes you’re letting them lie,” he snarled, straining until iron shuddered.

“Call me ‘animal’ again,” Isaiah said softly, jerking the chain just enough to hiss pain into Thomas’s arms.

“See if I forget what Mrs.

Carter asked of me.”

Sometimes Thomas appealed to me.

“Think what you’re doing,” he whispered.

“When they find out—Gideon, the sheriff, the judge—when they hear a woman conspired with slaves—”

“Then perhaps they will finally understand the cost of making half the human race helpless by law,” I said.

“Sleep well, husband.”

Gideon grew nosy.

“If your husband is ill… consider liquidating assets,” he said, sipping my tea.

“I can make… inconvenient details disappear.”

I smiled and pretended.

Time tightened like a noose.

We couldn’t keep Thomas there forever.

“Sooner or later someone will ask,” I said in the kitchen at night.

“Gideon smells blood.”

“Then finish it,” Isaiah said.

“Put a rope around his neck like they do to any of us.”

My stomach turned—not at his dying, but at the noose.

“No,” I said.

“He will not be a warning hanging in the yard.

That is their way.”

“What’s your way?” Esther asked—older, voice rough as gravel, steady as bedrock.

“I mean to end the Carters,” I said.

“Not just the man—the name, the claim, the house.”

“A fire,” Isaiah said.

“A fire,” I agreed.

“An accident.

Or natural result of a life spent stacking tinder and pretending not to smell smoke.

The house, the records, proof of ownership—everything binding this place to his name.”

“And us?” Ruth asked.

“What happens to us?”

“You run,” I said.

“I have some money hidden.

Not much.

Enough to—”

“To buy white folks looking the other way,” Esther cut in.

“To bribe sheriffs who’ve known you as Carter’s wife since knee-high.

You think your money spends the same in our hands?”

Brutally truthful.

I took a breath.

“Not simple.

Many may stay.

But there will be an opening.

A crack.

Decide if you wish to squeeze through.”

“And you?” Isaiah asked.

“You staying when it burns?”

I could run.

Disappear with a forged letter and coins.

Reinvent somewhere far from southern soil that soaked up my complicity.

But: “This is my house,” I said.

“My parents married me into it.

My name sits on deeds next to his, even if law pretends otherwise.

My hands poured drinks for men who planned whippings at this table.

My silence legitimized cruelty.

If the house burns and I run while you risk your lives in smoke, what am I except another Carter taking what she can and leaving ashes for others to breathe?”

“You ain’t him,” Ruth whispered.

“No,” I said.

“But I’m not innocent either.

If there is to be an ending, I will stand in it.”

Esther nodded first.

“Then make sure it’s worth the price.

Fires is like people—they tell on you if you don’t let them run wild.”

Preparations unfolded under routine.

Ruth “forgot” a candle too low in the pantry—counting how quickly flame took.

Esther tucked broken chair legs and worn broom handles in the cellar’s corner for a stray spark to work mischief.

Isaiah adjusted night chores—ensuring doors unbarred, shutters unlatched.

In the shed, Thomas moved from fury to bargaining to fear.

“I’ll sell land,” he pleaded.

“Free some of them.”

“You can ‘free some’ like furniture,” I said.

“You gave law its shape in this house.

It’s time law found you small.”

On the afternoon storm rolled from the west, sky bruised purple-green, air electric, lightning forked, thunder rolled like wheels of judgment.

“Storm’s a gift,” Esther muttered.

“Folks will blame lightning.”

We moved like sleepwalkers.

I walked halls, fingers ghosting polished banisters, portraits of solemn men and tight-lipped women whose wealth sat on bodies.

Before Silas Carter’s painting, I whispered, “You’ll be the last of your line.”

In my room, I wrote two letters—one banal to my sister, one confession to myself.

When fat drops smacked windows, Ruth came.

“It’s time.”

In kitchens, night fires banked low.

Esther moved among stoves, leaving one cupboard door ajar, rag hanging near flame.

Isaiah slipped to the shed and secured Thomas’s chains tighter.

He looked toward the house.

Our eyes met—his fist closed once: ready.

Smoke in the pantry; red glow leaping behind thin door.

Choking thickness as fire found old dry wood, jars of fat, brittle herbs.

Ruth ushered maids and boys.

“Get water! Run!” Sparks licking the ceiling, pantry door burst, flames climbing.

Someone screamed, “The house!” Rain hissed on flames crawling from a window.

The staircase caught.

Decades of polish turned inferno.

“Mrs.

Carter!” a footman shouted, grabbing my arm.

“We have to get you out.”

“Yes,” I said, pulling free gently.

“You go.

I’ll follow.”

Outside, silhouettes jerked against flicker.

Gideon rode up, cloak soaked.

“Evelyn! Where’s Thomas?”

“Lightning,” I gasped, letting smoke roughen me.

“The pantry.”

He barked orders.

Fire outpaced human hands.

Old houses burn fast.

Houses built on tinder, lies burn faster.

I stepped under porch roof, hand at throat.

Beyond yard, the shed stood dark.

Somewhere inside, Thomas screamed.

No one heard over storm.

I could have run.

Slipped into chaos.

Joined those edging toward tree line under “fetching water” pretense.

Let house and storm erase me.

My feet turned to the front doors.

“Evelyn!” Gideon yelled.

“Are you mad?”

“For once,” I called, words almost lost in roar, “I’m clearer than I’ve ever been.”

Inside, the main hall was a cathedral of flame.

Portraits curled; faces melted grotesque.

Smoke clawed lungs; heat pressed like a wall.

I stood at the stairs.

Our wedding portrait bubbled; smiling oil faces dripped.

My painted self’s head tore and slid.

The house groaned.

A beam broke like a giant’s bone.

Nights of rain, muffled cries, Thomas’s steady snore—ran through me.

The boy with the rope.

Jacob’s gray eyes.

Esther’s gnawed hands kneading bread.

Silas, Thomas—petty tyrants carved into pews and courthouse plaques as if that might make them immortal.

“Your line ends here,” I whispered.

Smoke rolled over me.

Isaiah later said he watched my dress vanish into glow and knew I had made my choice.

By dawn, the big house was a black skeleton, chimneys jutting like broken teeth.

The shed a charred stump.

Inside: cracked chains and bone fused to iron.

The official story fit neatly in public imagination.

“Tragic accident,” parlors murmured from Natchez to New Orleans.

“Lightning.

The Carters burned.” Whisperers over sherry spoke of unrest, sabotage; others shrugged: “God’s judgment.” No one spoke loudly enough to disturb their sleep.

Legal men picked through the estate like vultures.

Gideon acquired land in pieces, parceling to cover debts.

Some he farmed.

Some he sold.

Some he let lie fallow and remember.

As for the enslaved: a few sold with land; others slipped away in confusion, following whispers of Union lines far north; a handful vanished so thoroughly their names faded from records—swallowed by the slow eraser this country does so well.

Years later, decades by some accounts, a man stood at the edge of what had been Carter Plantation, trying to reconcile quiet with history.

Fields to grass.

The big house’s foundation a moss-covered rectangle.

Young pines sprung where quarters stood.

Stone steps remained, leading nowhere.

His name was Daniel.

His grandmother called herself Ruth.

He knelt, ran his fingers over worn stone, listened to ghosts—stories his inheritance.

Whispered tales up north of a white lady who turned on her own; of a man named Isaiah who walked away from a burning house and never looked back; of a fire not entirely the storm’s doing.

“Some folks say she was a devil,” his grandmother had told him, eyes milky with age, sharp with memory.

“Some say she was an angel.

Me? I say she was just a woman who’d spent too long looking the other way and finally turned her head right.”

Daniel felt no old fear that cracked his grandmother’s voice when she spoke of whips and chains.

He felt solemn gratitude.

He picked up a small stone, blackened, soot clinging after all these years.

He pressed it into the soft earth at the clearing’s edge and covered it.

“Let you stay buried,” he murmured.

“Not forgotten.

Just settled.”

Grass stirred, carrying away his words.

In its rustle, if a person listened hard enough, they might imagine echoes: a chain’s clank, fire’s crackle, a woman’s voice saying, “Your line ends here.”

The world moved on.

Railroads came and went.

Wars fought and commemorated.

Names carved on new monuments.

But here, among trees and birds and the slow healing of earth, the revenge that ended the Carters did something rarer than destruction.

It cut the root of a rotten tree and let the stump rot into soil—making room, perhaps, for something better to grow.

Some would say Evelyn Carter died a sinner.

They would not be wrong.

Some would say she died a saint.

They would not be right.

What she died—above all—was accountable: to the lives she touched, to the harm she helped perpetuate, and to the fire she finally chose to set.

News

The Pastor’s Wife Admitted Four Women Shared One Slave in Secret — Their Pact Broke the Church, 1848

They found her words in a box that should have turned to dust. The church sat on the roadside like…

The Paralyzed Heiress Given To The Literate Slave—Their Pact Shamed The Entire County, Virginia 1853

On the night the county gathered to watch a girl be given away like broken furniture, the air over Ravenswood…

The Judge’s Daughter Who Secretly Married Her Father’s Favorite Slave—The Trial That Followed, 1851

They said the courthouse had never held so many people. The air felt like wet wool—heavy with perfume, sweat, and…

The Plantation Lady Replaced Her Husband’s Heir With the Cook’s Slave Child—Georgia’s Silent Scandal

They say the storm that broke over Merryweather Plantation in the spring of 1854 was the worst anyone in that…

The Mistress Who Promised Freedom To The Slave Who Impregnated Her First—She Lied Twice

The first time I saw Helena Ward’s handwriting, it was bleeding through a ledger that should have held nothing more…

The 18-Year-Old Slave Boy Who Impregnated the Governor’s Wife — Virginia 1843

On the night Virginia decided what kind of child it would let a governor’s wife carry, I was still just…

End of content

No more pages to load