There are confessions that arrive too late to save anyone.

The one discovered in the water‑damaged strongbox beneath Laurelwood’s collapsed east wing was precisely that kind: a handwritten accounting dated April 1871, penned in the shaking script of a woman who once ruled 200 souls and 8,000 acres.

It admitted to deeds even Reconstruction courts would have considered too terrible to prosecute—not because they weren’t crimes, but because acknowledging them would have required white society to admit what it had always known and chosen to ignore: that desire, when given absolute power over human flesh, does not stop at boundaries of race, law, or decency.

It devours until the devourer is consumed.

Laurelwood Plantation lay seventeen miles west of Natchez, Mississippi, on land so rich you could grow cotton without fertilizer and so isolated you could commit any sin without immediate witnesses.

Yet witnesses were everywhere—watching from the quarters, listening through walls, remembering for a day when remembering might become profitable, necessary, or simply unbearable to keep silent any longer.

The estate had been built in 1834 by Colonel Edmund Ravoux, a Louisiana Creole who made his fortunes in sugar and then cotton speculation.

He married his daughter, Celestine Ravoux, to a Virginia gentleman named Marcus Havelock—purely because the Havelock name carried bloodline weight money could not purchase outright, though it could certainly rent for the span of a strategic marriage.

By 1857, when our story properly begins, Colonel Ravoux had been dead six years, Marcus Havelock three.

Celestine Ravoux Havelock at thirty‑four found herself in that dangerous position peculiar to Southern widowhood: absolute mistress of a property and its people, answerable to no living man, governed only by social structures she had been raised to enforce—which meant governed by nothing at all, once drawing room doors were closed, account books could be altered, and overseers dismissed for asking inconvenient questions.

She was not conventionally beautiful—face too angular, mouth too determined, eyes so dark they absorbed light rather than reflected it—but she possessed presence, the French kind: the quality of making every person in a room aware of her, bending attention toward her through sheer contained intensity, like iron heated just short of glowing.

She dressed in the latest fashion ordered from New Orleans and sometimes directly from Paris, and she ran Laurelwood with military precision.

She knew the yield of every field, the health of every enslaved person, the price of cotton in Liverpool and New Orleans, the social standing of every family within fifty miles, and which secrets might be deployed if anyone questioned her management, her choices, or her increasingly frequent absences from church.

On the surface, Laurelwood’s order was exactly what it appeared—rigid and carefully maintained, like the formal gardens Celestine installed at great expense.

At the top: herself, the mistress, whose word was absolute.

Below: white overseers—she went through seven between 1854 and 1860, dismissing each for drinking, incompetence, or unreliability (her word for men who asked too many questions about her nighttime movements or peculiar privileges granted to certain enslaved men).

Below them: house servants—Uli, Celestine’s maid since childhood; Baptiste, the butler with such quiet dignity visitors sometimes mistook him for free; Marguerite, the legendary cook whose silence was absolute.

Beyond them spread the quarters in careful gradations of status and function: field hands, 217 souls in 1857, 243 by 1860—not all of the increase from purchase or natural birth.

There, the unraveling’s first thread was tied.

The law said one thing, scripture another, social custom a third.

What governed Laurelwood was simpler and older than all that: proximity to power—and what one would do to maintain or increase it.

Celestine understood this perfectly.

She’d watched her father manipulate black and white through rewards and punishments, privileges and deprivations.

She learned power’s most reliable tool wasn’t violence (though violence had its place), but cultivated hope.

Give people something to hope for—something to strive toward—and they’ll endure anything.

Distribute hope unevenly, and you create competition.

Competition serves those at the top.

So no one initially questioned when Celestine began showing unusual favor to certain male enslaved people: field hands between twenty‑five and thirty‑five; men of unusual bearing—tall, well‑made, healthy in a way that stood out even among Laurelwood’s robust population.

They were brought into the house for “special tasks.” They received better food, clothing, small privileges that meant everything in a world where each comfort was controlled.

The mistress spoke to them—sometimes at length, sometimes in the evening, sometimes in rooms with no other witnesses.

The first was Samuel, purchased in 1855 from a failing Alabama plantation, a man who could read (illegal, but not uncommon).

Celestine assigned him to catalog the Laurelwood library—a task requiring hours in the house each day.

The second was Jacob, born at Laurelwood, suddenly promoted from fieldwork to groundskeeping—working the ornamental gardens visible from the main windows, visible to Celestine throughout the day.

The third, Isaiah, arrived from New Orleans in 1856; auction bills called his features “refined,” a private journal fragment later called his face “belonging to a different century when such things were celebrated rather than hidden.”

What began between Celestine and these men wasn’t sudden, simple, or easily categorized.

In private writings—fragments surviving despite pages torn or burned—she described a mix of obsession; rebellion against the order she enforced; and genuine feeling with nowhere legitimate to exist, twisting itself into shapes that could fit the cracks of Laurelwood’s hierarchy.

“There are desires,” she wrote in March 1856, “that cannot be spoken, acknowledged, or even thought in full daylight, but which become undeniable when the house is quiet and accounts settled, when nothing stands between oneself and the darkness except the truth that we are all, regardless of law or custom, creatures of appetite—and appetite recognizes no boundary except its own satisfaction.”

Samuel came to the library at nine each morning.

At first: functional interactions.

She would direct; he would work in silence while she read or wrote correspondence.

But silence in the same room day after day makes intimacy.

They spoke.

She tested his literacy; he quoted Milton, then Virgil—in Latin.

She asked how he learned.

From a previous master’s son, he said—first as a game, then from genuine affection for teaching—until the master discovered it and sold Samuel south to punish both teaching and affection.

Conversations deepened.

She brought better books.

She asked opinions on what she read—framing it as testing comprehension but hungry for intellectual conversation she could not have with her social circle’s women (educated for accomplishments, not ideas) or with men who would be scandalized by a woman with opinions on political philosophy.

Samuel engaged and challenged.

His mind met hers without gallantry or condescension.

In return, she gave him access: knowledge, books, conversations treating him as something other than property.

It was Samuel who carefully suggested, obliquely, that some boundaries exist only because people agree to see them—and some freedoms might be taken in private spaces where rules do not reach.

It was Celestine who, after three months of increasingly charged conversations, locked the library door one August afternoon and crossed a boundary that, once crossed, could never be uncrossed.

She told herself it was a momentary lapse—singular, unrepeatable, certainly undiscoverable.

Desire, once acknowledged and satisfied, does not diminish.

It multiplies.

Power mixed with desire becomes something else: a madness that feels like clarity; transgression that feels like truth; violation that convinces itself it is honesty in a world built on lies.

Jacob came next, six months later.

Where Samuel was intellectual, Jacob was physical—a man who understood growing things.

Celestine walked the gardens in the evening; Jacob was there; she asked about plants; he answered with knowledge and genuine feeling.

He loved the gardens.

That love opened a path: mistress to enslaved, but as two people caring about beauty.

A pattern formed—she told herself each man was unique, each connection justified, every boundary crossing specific.

In retrospect, it was a shadow household: a parallel family bound by desire, dependence, and dangerous secrets—ties more absolute than marriage.

She convinced herself this intimacy was truer than any lawful union.

Isaiah arrived in November 1856, with the first hints others were noticing.

Celestine insisted on purchasing him despite her overseer’s objection (too high a price, too delicate for fieldwork).

She assigned him to the stables attached to the house—visited daily ostensibly to check horses, actually to establish private space as with Samuel and Jacob.

Uli, the maid who’d known Celestine since childhood, tried to warn her.

In testimony recorded in 1871—by then elderly—Uli recalled telling her mistress: “People talking—not saying nothing direct—but talking around the edges; saying you show favor; saying there’s more going on than proper.” Celestine went cold and said, “People may say what they like.

I run this plantation as I see fit and will favor whomever performs well.

If others are jealous, they may earn privileges through better work.” Technically reasonable; fundamentally evasion.

Even so, the warning had an effect.

She became careful about timing, locations, who might observe.

She sent Uli on errands.

She locked doors that had never been locked.

She adjusted routines to create privacy pockets.

And she began making cash payments to certain enslaved people—recorded as “discretionary bonuses”—purchasing silence, binding people through complicity, dissolving community into individuals pursuing their own advantage and therefore hiding what they saw or suspected.

By 1858 there were five men in her shadow household: Samuel, Jacob, Isaiah; Thomas, a carpenter whom she commissioned to build a cottage in the woods beyond the formal gardens—officially for storage, actually for privacy; and Daniel, twenty‑five, purchased from a South Carolina plantation, listed as “intractable; prone to running.” Undesirable on paper; interesting to Celestine.

Submission from him would mean something because it would be given rather than simply extracted.

The cottage became the center.

Completed in summer 1858: small, well‑built, furnished better than the quarters, isolated enough that sounds wouldn’t carry.

Celestine spent time there sometimes alone, sometimes with one of her chosen men, sometimes—with more than one.

Gatherings were ostensibly work planning or illegal literacies (arithmetic, reading) justified as practical: educated labor is efficient, valuable—and who would question her? She owned them.

She owned everything.

But what pleased her increasingly lacked justification.

The cottage gatherings acquired ritual: specific days, times, combinations.

She brought food from the house, good wine, treats otherwise unavailable; books, paper, ink.

She created a space where Laurelwood’s hierarchies were suspended—where conversation was frank; where, for a few hours, she could ignore the reality that she owned them; that everything between them, however much it felt like choice, was coerced.

Samuel understood first that it could not last.

In a fragment found decades later in an Ohio church archive (he escaped north in 1859), he wrote: “She believed she could have two lives—daylight, where she mistress and we slaves; darkness, where we something else she could not name.

There is no two lives.

Secrets of dark bleed into daylight, then everything collapses.”

The bleeding began with pregnancies.

In most contexts a pregnant enslaved woman was business: children born enslaved increased property value.

Masters encouraged breeding.

But at Laurelwood—starting in 1857 and accelerating—several women in the quarters became pregnant outside usual patterns.

Four initially, then three more—women not married in the informal sense; not known to be in relationships—pregnant at times coinciding with their connection to the men in Celestine’s shadow household.

The truth, pieced together later from birth records, testimony, account books, privileges and punishments: Celestine orchestrated pregnancies.

She sent her men to specific women at specific times.

Some women were told directly; others approached indirectly through privileges or threats.

Motivations were complex, only partly coherent.

She wanted children carrying her chosen men’s blood; wanted an extended family tied to her through multiple bonds; wanted lasting connections even if direct relationships were discovered and ended—children who would grow up at Laurelwood remembering their fathers were special, chosen, favored.

She wanted darker things: to control reproduction, to play God, to prove she could manipulate the most fundamental human function to suit her design.

Journal entries grew unhinged.

She wrote of bloodlines, creating “better” enslaved people, mixing her chosen men with “strongest” women to produce children of superior intelligence and capability.

Pseudoscientific language borrowed from racial theories used to justify slavery, twisted to serve her obsession.

She wanted to breed people like horses—selecting traits—to create a legacy outlasting her life.

The sixth and seventh men entered in 1859.

Moses—a long‑time Laurelwood resident and informal quarters leader whose cooperation she needed for the breed plan to avoid open rebellion; and Luke (the records sometimes render “Lug”), purchased in spring specifically because a trader mentioned he’d fathered multiple healthy, clever children at his previous plantation.

Celestine paid premium prices, raised eyebrows, and immediately granted privileges—creating resentment among enslaved people and suspicion among whites who noticed Laurelwood’s internal workings.

By late 1859, the situation was unsustainable.

At least seven women were pregnant or recently delivered—with questionable paternity.

Whispers spread in the quarters and beyond.

Planters’ wives hinted at church socials that Celestine looked thin; distracted; had missed social events; plantation management seemed erratic despite profits.

New Orleans relatives—Ravoux connections—suggested she needed male guidance, needed to remarry, needed to restore order before property value and family reputation suffered irreparably.

Tensions in the quarters rose.

Favoritism created the competition she had once considered useful, now dangerous.

The chosen men enjoyed privileges others envied; the women selected for breeding (or who volunteered hoping to improve circumstances through connection to favored men) were resented by those not chosen.

Families were disrupted by interventions.

Children were born who did not fit into normal kinship; who belonged to no clear family unit; marked as special—becoming targets.

Samuel tried to leave.

He ran in November 1859, made it to Tennessee, was captured.

Typically, a runaway would be severely punished, perhaps sold away.

Celestine did not.

She locked herself in the library with him for an afternoon.

Whatever was said, Samuel afterward seemed broken in ways whipping would not achieve.

He stopped speaking nearly entirely; performed duties with automation, his mind elsewhere—already gone though his body remained.

Jacob went to Uli—told her it had to stop—that someone Celestine trusted needed to warn her.

Uli, torn between childhood loyalty and horror, tried again.

This time Celestine didn’t brush it off.

She sold Uli.

After twenty‑five years of service, after a relationship as close to family as slave‑mistress could be, Uli was sold to a Texas plantation—sent far where she couldn’t speak to anyone who knew Laurelwood.

Couldn’t testify nor gossip nor warn.

The sale shocked everyone: If Uli could be sold, anyone could.

Message clear: silence mandatory; breaking it meant exile or worse.

The sale also marked Celestine losing the moral authority needed to hold the structure together.

Few house servants remained loyal; they calculated interests.

The men realized they were disposable; her desire did not protect—it made them vulnerable because they knew too much.

Winter 1859 into spring 1860 brought paranoia and chaos.

Celestine kept a pistol; stopped sleeping in her bedroom, moving unpredictably; dismissed another overseer; hired another; dismissed him within a month.

She sold several enslaved people suddenly; panic about who might be next.

She intensified cottage visits, sometimes staying overnight—surrounded by chosen men—as if it were a fortress and they guards rather than prisoners serving as intimates.

The collapse was precipitated by something minor and inevitable: one child born of the program looked unmistakably like Isaiah but equally unmistakably carried recent white ancestry.

The mother, Sarah, dark‑skinned, with no known white ancestry; the boy’s skin amber in sunlight; refined features not explained by Sarah alone.

Isaiah, classified as black under law, was light‑skinned enough that rumors said his grandmother had been white.

The calculations of race—obsessive and complex—put the child near white; social anxiety in that category threatened the absolute boundary slavery required.

Planters asked questions.

A visiting doctor commented on unusual coloring, asked indirect questions about paternity.

Questions reached New Orleans.

Ravoux relatives, already concerned about Celestine’s unmarried state and eccentric management, suggested directly she needed male supervision—remarry—to restore order.

Celestine doubled down on secrecy.

She moved Sarah and the child into the cottage; ordered silence on pain of sale; began plans to send certain enslaved people west to distribute evidence across geography so pattern would be invisible.

She waited too long.

In August 1860 a Ravoux cousin arrived, a lawyer named Marcelin, sent to assess and, if necessary, assume management using legal tools available to men controlling female relatives’ property.

He spent a week; asked pointed questions; inspected quarters; examined birth records; within three days he understood broad outlines.

His report, preserved in family papers, avoided explicit statements of sexual conduct but was clear: irregularities; inappropriate favoritism; concerns about moral atmosphere; strong recommendation she remarry or accept direct family oversight.

The confrontation was witnessed by Baptiste.

Celestine’s response was not shame but fury.

She told Marcelin Laurelwood was hers; managed more profitably than her father; owed no explanation.

Marcelin remained calm—explained that while she owned Laurelwood, her behavior damaged the family’s reputation—and reputation was property, perhaps more valuable than land.

The argument ended in stalemate.

Marcelin returned to New Orleans without immediate action—but action would come unless Celestine modified behavior.

Celestine made a catastrophic decision: eliminate evidence.

She would sell all seven men, scatter them across states, make reconstruction of pattern impossible; gradually dispose of children—selling them young before parentage became obvious; before they could testify or remember.

She began with Moses, sold in September 1860 to a trader heading to new territories; then Luke, sold to an Arkansas plantation.

The abrupt sales terrified everyone—they proved her desire, which seemed protection, was a marker of disposability.

The most intimate men were the first sacrifices; they knew the most, threatened the most, posed the greatest danger to her reputation.

Selling witnesses doesn’t eliminate secrets; it spreads them.

Moses talked.

Luke did too.

Their stories were fragmentary, confused, probably exaggerated, certainly not believed by most white listeners—but they circulated nonetheless through slave networks, plantation gossip, whispered testimonies accumulating into collective knowledge even if no single story was credited.

Thomas tried something else.

He went to a Natchez white minister known for anti‑slavery sympathies; attempted to give testimony.

The minister, confronted with scandal too startling, told by a man with suspect motives, took no immediate action—but documented the conversation.

His notes became part of the official record once war changed everything and testimony from formerly enslaved people began being taken seriously.

Samuel, Jacob, Isaiah, Daniel realized they had a narrow window before they, too, would be sold.

They made a collective decision to run in October 1860.

Four men fleeing together—valuable, recognizable—was a massive risk.

They gambled that the approaching war’s chaos—secession openly discussed, militias forming, slave patrol mechanisms fraying—would distract enough to succeed.

Three were caught within a week.

Jacob was killed resisting recapture—shot by a patrol claiming he attacked, though witnesses said he refused surrender and they shot rather than bring him back.

Samuel and Isaiah were returned.

Celestine did something revealing how disconnected her mind had become: she imprisoned them in the cottage—the same space of gatherings—and kept them there, locked, bringing food herself, visiting daily, trying to recreate intimacy—as if imprisoning could restore what had been lost.

Daniel alone escaped north—eventually in 1862.

His testimony to Union officers and later the Freedmen’s Bureau was the most detailed account of Laurelwood—describing the breeding program, cottage gatherings, Celestine’s increasingly delusional justifications.

It formed the basis of the legal case that would destroy what remained of family reputation.

War came.

The old order ended.

Laurelwood was occupied by Union troops.

In April 1863, soldiers discovered Samuel and Isaiah—half‑starved, traumatized, alive, willing to testify.

Legal proceedings began in 1865, dragged to 1871—complicated by Reconstruction chaos and difficulty categorizing Laurelwood under any legal framework.

Was it rape? Almost certainly—no enslaved person could consent to anything demanded by an owner.

Kidnapping? False imprisonment? Yes—especially for cottage confinement.

Fraud for manipulating birth records? Perhaps.

Or simply slavery’s “normal operation”—legal until 1865—always involving sexual exploitation, forced breeding, absolute control.

Prosecuting or even describing Celestine exposed system hypocrisy: acknowledging her would require admitting such things were endemic to slavery; that master‑slave power imbalance always created opportunities for exploitation; that if she was guilty, countless others were, too.

In the end, no criminal charges were filed.

She was judged insane—protecting both her and a society preferring not to examine itself—and committed to a Louisiana asylum, where she died in 1874 at fifty‑one, insisting she’d done nothing wrong—that she acted on property rights—that her cultivated intimacy was kindness, a gift they should have thanked her for.

The real reckoning came as the children of her program came of age and sought truth of parentage.

At least seventeen children can be traced to her plan—born between 1857 and 1860 to mothers deliberately selected and paired with her men.

Some sold away young—lost to war chaos.

Others remained near Natchez, grew up free, investigated histories once old enough to ask—and entitled to answers.

The discoveries appear in Freedmen’s Bureau records from people seeking family, church birth registries with baptisms listing parental information contradicting slave birth records, pension applications for Union veterans requiring proof, and Laurelwood’s own papers—eventually sold, but preserved in county archives.

A pattern emerged: kinship web connecting dozens across black and white lines—violating every social boundary the South constructed.

Children were related to each other, and through fathers to other children.

Some men had fathered before the program; some were distantly related to Celestine herself—Ravoux cousins, kinship recognized in Creole genealogies but obscured by legal fiction that reduced them to property.

The most disturbing discovery came in 1897, when a New Orleans lawyer working a Ravoux inheritance case noticed something strange in Laurelwood’s birth records: a woman listed as Saraphene who gave birth as part of the program was Celestine’s half‑sister—the daughter of Colonel Ravoux and an enslaved woman named Marie—a fact known but never officially acknowledged.

That meant when Celestine selected Saraphene to bear Isaiah’s child, she orchestrated her own half‑sister’s pregnancy—creating a child simultaneously Celestine’s nephew, Saraphene’s son—and, given Isaiah’s ancestry, likely carrying Ravoux blood through multiple lines—a tangle exposing slavery’s lie: that black and white were separate and that bloodlines could be controlled and categorized.

The revelation shattered what remained of the Ravoux standing.

Unacknowledged mixed relations were common—expected—never spoken.

Documented connections, provable through records and testimony, were different.

The family tree could not be drawn with clean lines; it was a web of unions across boundaries, generations—creating descendants in legal and social categories with no proper name.

The case that finally emerged in 1899 was brought by Katherine Laveau—a woman claiming to be Saraphene and Isaiah’s daughter, making her Celestine’s niece—arguing entitlement to Ravoux property on grounds that Louisiana law recognized certain rights of illegitimate children to inherit and that Isaiah’s lineage tied him to the Ravoux line.

Legally absurd—dependent on connections crossing race, slavery, legitimacy—no court would uphold without undermining inheritance and racial classification.

But her evidence was devastating because it was true.

Birth records were authentic; connections real.

The Ravoux faced choosing public refutation requiring acknowledging and then justifying the history—or settling quietly.

They settled.

The amount was small; the precedent enormous: white society acknowledged in a binding document that descendants of the program had claims—moral, if not legal—that could not be dismissed.

Other descendants came forward—not with lawsuits, but demands for recognition and truth of parentage to be recorded.

By 1905, court cases settled, Laurelwood property sold off, the house demolished, the cottage burned to eliminate a local shame landmark.

Enough documentation existed to reconstruct what happened with terrible clarity: Celestine orchestrated controlled breeding over four years producing at least seventeen children; maintained sexual relationships with at least seven enslaved men (relationships coercive by definition); imprisoned men who tried to escape; sold away witnesses; attempted to engineer a dynasty outlasting her—legacy built not through her own lawful children (she had none), but through children born to enslaved women, according to her design.

What she created was darker, more enduring: a population carrying proof of slavery’s corruption in their existence—genealogies as living testimony that boundaries between master and slave, white and black, family and property were maintained through violence and willful blindness; descendants spending generations piecing histories from fragments and silences and documents designed to obscure truth.

In 1908, a Natchez courthouse clerk reorganizing old records found a sealed envelope misfiled among 1850s property deeds: “To be opened only after my death—C.

H.

(Celestine Ravoux Havelock).” He opened it expecting a will or property instructions.

Inside: a letter, seventeen pages, Celestine’s hand, dated April 1871, written during proceedings that occupied her last years before the asylum.

Addressed to no one—or everyone—or history.

Celestine attempted explanation—less justification than confession.

She wrote of loneliness—the prison widowhood created for a woman of intelligence and appetite; the impossibility of finding legitimate outlets for intellectual and physical desire in a society demanding women be decorative and passive.

She wrote of power—the intoxication of bending human beings to her will—deploying absolute authority beyond its architects’ intent.

She wrote of conviction—delusional by 1871, perhaps not at the start—that she was engaged in social experiment: improving enslaved population; creating better future through careful selection and breeding.

She wrote, too, of genuine feeling for some men—painful to read not for handwriting, but what it revealed.

Conversations with Samuel shaped her politics and philosophy; Jacob’s understanding of beauty and growth; Isaiah’s gentleness; Daniel’s fire; Thomas’s steadiness.

She described them as people she loved—perhaps, in twisted ways, she did.

But the love was inseparable from ownership; expressed through control and manipulation; love that demanded everything and gave only the illusion of reciprocity—indistinguishable from cruelty.

Near the end came the most chilling passage about the children:

“They are my legacy, though they will never bear my name.

They carry the best blood of those I chose, and they carry it into a future I will not see, but that I have shaped.

Let those who judge me understand I did not act from mere appetite, but from a vision of what might be possible if power and desire were united in the service of creation rather than destruction.

I made something new at Laurelwood.

That it was made in secret; that it violated the laws of God and man; that it has brought ruin rather than glory—these I cannot deny, but I made it nonetheless, and it will outlast me.

Perhaps someday those who share that blood will understand what I attempted, even if they cannot forgive how.”

The letter entered court records, reprinted in newspapers, creating the scandal her family had spent decades avoiding.

By 1908, the world had changed; the scandal was historical rather than immediate; it reflected on slavery rather than specific living family members.

The Ravoux name survived—diminished but intact.

Laurelwood was gone; land subdivided; house rubble; cottage ashes.

The enslaved were dead or scattered; their children building lives with nothing to do with the plantation that shaped their parents’ existence.

The deeper legacy remained: recorded in genealogies and DNA, in birth records and family stories, in features appearing unexpectedly generations later, in psychological scars trauma inscribes not just on individuals but lines carrying forward silence and secrecy and shame.

When enough participants had died that speaking wouldn’t endanger anyone, when time had turned immediate pain into historical curiosity, truth had become almost impossible to reconstruct completely—those who knew firsthand took knowledge to unmarked graves; survivors chose silence over testimony—protection over revelation.

The seven men drawn into Celestine’s program had seven fates—and their fates clarify Laurelwood’s full measure.

Samuel escaped north; survived war; died in Cleveland in 1882—trying to create the intellectual independence he briefly tasted in Laurelwood’s library.

He never married; had no recorded children.

A letter describing his experiences suggests a man so damaged by hope and betrayal that intimacy was too risky.

Jacob died fleeing—buried in an unmarked grave in woods between Laurelwood and Natchez—his death recorded only in a slave patrol notation: “Negro Jacob, property of Havelock Plantation, killed resisting capture.

Oct.

15, 1860.”

Isaiah, freed by Union soldiers, remained near Natchez; married a woman named Ruth; had five more children beyond those born at Laurelwood; never spoke about his experiences there.

When asked about older half‑siblings or tangled family history, he said only, “That was slavery times.

We don’t talk about slavery times.”

Daniel, the youngest, testified extensively for the Freedmen’s Bureau and legal proceedings; found some measure of healing in speaking truth; but paid.

He was harassed, threatened, called a liar.

He moved to Chicago; died in 1889.

His testimony sits in archives few people read.

Thomas was sold before the war ended; disappeared into the vast displaced population; his only record a minister’s note.

Moses and Luke were sold west; left no surviving records beyond names in account books and birth records of children fathered under her program—their stories reduced to blanks.

And the children—at least seventeen documented—grew up in a world transformed by war and emancipation.

Legal structures enabling their creation no longer existed; social structures remained.

Some prospered in the limited ways possible; some were destroyed by poverty, violence, or accumulated trauma; some moved north or west; some stayed near Natchez—close to ruins and graves, as if proximity to the source was necessary to understand, even if understanding brought no peace.

A last document surfaced dated 1910, fifty years after Celestine’s program peak: a letter from Katherine Laveau (Saraphene and Isaiah’s daughter—the woman who sued) to her own daughter, explaining family history hidden and denied.

Matter‑of‑fact, unsentimental, almost clinical—but ending with something essential about Laurelwood, and why the story matters:

“I write this not to shame our ancestors—neither those enslaved nor those who did the enslaving—but to tell you the truth, so you may know where you come from and what was done to make you possible.

You are the product of love and rape, desire and ownership, hope and exploitation.

You carry in your blood the proof that the old order was built on lies; that the lines they drew were false; permeable; maintained by violence and denial rather than any natural truth.

“When they say slavery was a particular institution with its own rules and that Laurelwood was exceptional—an aberration—they are lying.

Laurelwood was slavery taken to its logical conclusion: absolute power over human beings exercised without restraint.

Your great‑grandmother—yes, Celestine Havelock was your great‑grandmother—did terrible things.

She did them within a system that made such things possible and even inevitable.

“The ritual that ended her dynasty was not voodoo or conjuration, but truth—emerging from decades of secrecy, proving that no amount of power or money could hide what had been done, or prevent consequences from echoing forward.

You are one of those consequences.

So am I.

So are dozens whose names you’ll never know.

We are what survives when plantations burn, records scatter, and people who knew full truth are dead.

We are evidence that cannot be destroyed—testimony written in bone and blood.

Remember that, and tell your children, so truth does not die with us.”

The letter was preserved, donated to a historical society, became part of the archive that made reconstructing Laurelwood possible.

In that preservation—in refusing to let comfortable lies stand—lies whatever redemption the story might contain.

Not in the events themselves—irredeemable—but in descendants’ insistence on remembering, on refusing moonlight‑and‑magnolia myths of benevolent masters and contented enslaved people and tragedies that were somehow beautiful.

Laurelwood was not beautiful.

Celestine Ravoux Havelock was not misunderstood, ahead of her time, or tragically romantic.

The men she drew into her program were not willing participants in grand passion; they were human beings trapped in an impossible system, making choices that weren’t choices, surviving as best they could.

The children born of her program were not products of love, but of ownership—of presumption that some people could use others’ bodies to fulfill their desires or designs.

Genuine feeling might have existed somewhere in the mess of power and coercion and loneliness.

It does not transform rape into romance—or breeding programs into family planning.

This is the story buried for decades—too scandalous to tell while participants lived, challenging too many comfortable narratives about slavery.

This is the ritual that ended a dynasty—not magic or murder, but truth—speaking itself in documents, testimony, and bloodlines that could not be denied, destroying reputation and inheritance and carefully constructed mythology of a family that believed its name, money, and position could protect it from accountability.

Laurelwood’s ruins are gone—plowed under, built over, transformed into cotton fields, pine forests, now suburban developments where people live who’ve never heard the story.

The cottage was burned in 1872—by descendants, by white locals erasing shame, or by vandals with a match.

The main house was demolished in 1905—timbers and bricks salvaged elsewhere.

Its presence erased so thoroughly that only research and ground‑penetrating radar find the foundation.

But stories survive when buildings don’t.

DNA survives.

Records survive—fragmentary, scattered—but recoverable by anyone willing to spend time in archives and courthouses, piecing truth from account books, birth records, depositions, private letters never meant for strangers but now historical evidence, testimony that cannot be silenced though all witnesses are dead.

The past isn’t past.

It’s written in genealogies, institutions, and our unexamined assumptions about who has power, who doesn’t, who gets to tell their story, and whose story is erased.

Laurelwood is gone.

What it represented—the corruption at the heart of absolute power, the human cost of treating people as property, and the tangled legacies such treatment creates—remains urgent.

It remains unresolved.

And it remains a truth we are still learning to face.

News

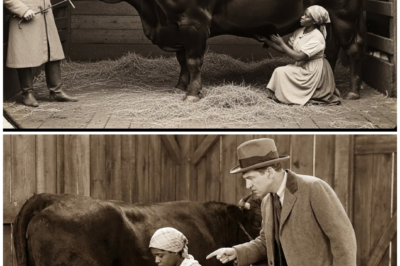

Plantation Owner Made His Slave “Breed” with His Prize Bull… Blamed Her When Nothing Happened…

They say the east barn is cursed, though the boards have rotted, the roof caved in, and the pasture gone…

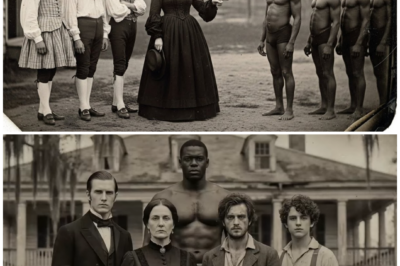

A Widow Chooses Her Strongest Slave For Her Effeminate Sons… The Darkest Secret, South, 1847

The widow made them line up bare to the waist under the white glare of the afternoon, as if they…

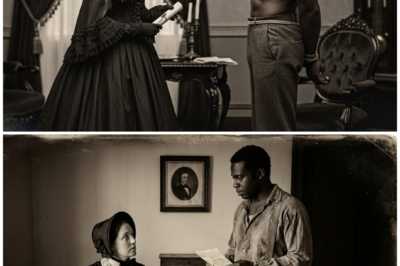

Young Slave Called to Fix the Master’s Bed Finds His Wife Waiting Instead (Alabama, 1779)

They said it began with a loose bed slat. That’s how the story was polished for parlor corners and pew…

The Virgin Widow Who Bought a ‘Breeder’ Slave for $2,000 — The Secret (1844)

In the winter of 1844, the slave market at the edge of New Orleans smelled of molasses, sweat, and a…

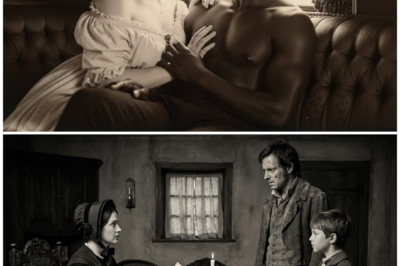

A Widow’s Secret: She Bought Her Own Son’s Father to be Her Lover (1837)

In 1837, the New Orleans slave market smelled like salt, sweat, iron, and something a city learns to call normal….

The master’s son secretly cared for the enslaved woman –2 days later something inexplicable happened

The whip cracked through the humid Georgia air with a sound like a tree splitting in a storm. Naomi’s body…

End of content

No more pages to load