They found her words in a box that should have turned to dust.

The church sat on the roadside like a skull—white paint peeling, steeple crooked, windows boarded shut.

Kudzu climbed its sides in slow green ropes, and the cemetery behind it had begun to swallow its own stones.

Nobody came anymore.

Not for weddings, not for funerals, not even for ghosts.

Only the county’s plan to tear it down put a key in the lock that summer.

When workmen pried open a closet behind the pulpit, they found a cedar chest, darkened by time, warped at the corners.

Under mold-spotted hymnals, beneath a folded black shawl stiff with age, lay a stack of pages tied with faded blue ribbon.

The ink was brown.

The script was thin and deliberate.

On the first page, in a hand wavering between pride and terror:

“A confession truly meant.

By my own hand, Sarah Anne Whitlow, wife of the Reverend Josiah Whitlow, in the year of our Lord 1848.”

What follows is what she wrote.

I have only arranged the line breaks so you can follow it out loud.

The voice, the sin, the shame—they are all hers.

—

I was twenty when I married Josiah.

The ladies said I was blessed above measure.

A man of God, a pulpit, a parsonage, the center chair at every church supper.

They looked at me with admiration braided into envy, and I wore that look like a second veil.

By twenty-three, the veil had torn.

Our little town clung to its church the way a drowning man clings to a log.

The fields gave cotton and corn.

The river brought trade and fever in equal measure.

By August, the sun burned everything—skin, shirts, even our Sunday best—to the same dull color.

Only the church stayed bright: white clapboards, straight steeple, bell polished with pride.

They called my husband shepherd of souls.

They called me mother of the congregation.

Behind closed doors, there were other names spoken only in my head.

The parsonage stood just behind the church, a narrow two-story with a sagging porch.

I filled it with needlework, polished pewter, and the smell of baking drifting into weekday afternoons.

Women came to me with their troubles: husbands who drank, children who backtalked, dresses that no longer fit.

I listened.

I nodded.

I prayed with them in the parlor beneath a cross-stitched verse—As for me and my house, we will serve the Lord.

All the while, my own house had a room no one entered but me.

It was the room where my marriage lived its slow death.

Josiah was not cruel in any simple way.

Cruelty would have given me something to push back against.

He was distant, the way men are who love God more as an idea than as a living flame.

His true bride was his sermon.

His intimacy was with the Book.

When he turned to me, it was out of duty, like a man winding a church clock.

There are places in a woman that shrivel when touched only from obligation.

There are other places that begin to hunger.

I thought I was strong enough to starve them.

For a time, I was wrong.

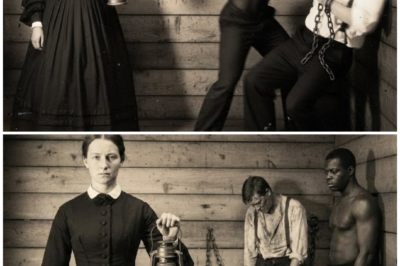

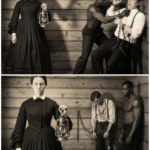

We owned three enslaved souls when I first came to the parsonage.

Old Martha, who cooked and muttered prayers not ours under her breath; Lotty, fourteen, who did the washing and stared with eyes too old for her thin wrists; and a boy—no, I must say man—who had come as part of a gift to the new pastor.

His name was Isaiah.

He was twenty-two that first season—tall but not towering; shoulders shaped by years of forced labor; a quiet that disturbed me more than any backtalk might have.

His skin caught the light like polished walnut.

His hands were scarred from rope and hoe and uncounted small violences.

His gaze never lingered on the family Bible.

Never on the table set for guests.

Never on me.

I told myself I was grateful for that.

I told myself many things in those days.

Isaiah slept in a narrow room behind the kitchen.

He rose before sun to haul wood, draw water, sweep the church, tidy the graveyard, fix whatever the congregation had broken.

He moved with a smooth economy—never wasted a gesture, never made more noise than necessary.

In a house full of words—Scripture, gossip, counsel, hymns—his silence was its own language.

Sometimes, watching from the window as he straightened grave markers or climbed a ladder to clean the eaves, I felt a prickling in my chest.

It was not attraction at first.

It was offense.

How dare he move with such quiet dignity when his body belonged to us? How dare he look like a man and yet be counted as property?

Offense became curiosity.

Curiosity became something else.

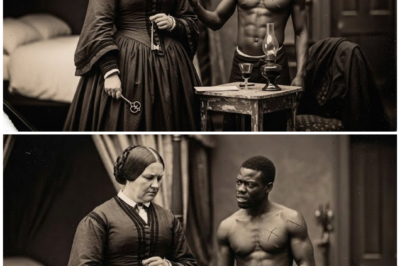

The storm that broke me came in July.

The air was thick enough to press between your fingers, sky gone to that peculiar yellow that means trouble.

By evening, the world narrowed to rain and wind and lightning splitting the sky like the finger of God.

Josiah had gone to sit with a dying man three miles out and had not returned.

I paced with a lantern, thunder repeating the same thought over and over:

What if he does not come back?

Not because I feared widowhood.

Because I felt nothing at the thought of his absence except inconvenience and scandal.

My marriage was already a widow.

Water leaked through the front bedroom ceiling.

Old Martha shouted the church roof was taking a beating too; if rain took hold, rot would follow.

“Isaiah,” I called, too loud for a storm.

“Get up to that roof.

Nail whatever’s loose before the Lord sends His house into the river.”

He stepped into the kitchen doorway soaked already from the threshold.

His shirt clung.

Mud speckled his trousers.

For a moment I saw him not as an object moving through tasks, but as a man in my kitchen, chest rising, water running down his jaw.

“Ma’am,” he said, “it bad lightning out.

Roof might not be safe.”

The words were reasonable.

I heard defiance.

“You’ll do as you’re told,” I snapped.

“Or will you answer to the Lord when His house caves in?”

He said nothing.

He took the hammer and sack of nails and went into the storm.

From the bedroom window I watched him climb the slick ladder.

Rain blurred his shape.

Lightning flared white and for one long second he was outlined against the bruised sky—arms outstretched for balance, body braced against fury overhead.

He looked like a man nailed to nothing, holding up everything.

When he came back shivering, my anger had dissolved into something far more dangerous.

He left wet footprints down the hall.

“You can’t go down there like that,” I said, voice tight.

“You’ll soak the floor.

Stay in the kitchen.

Martha—fetch a towel.”

Martha’s eyes flicked between us quick as a bird.

She handed me rough linen and shuffled off, muttering to the stove.

I stood with the towel in my hands.

Rainwater dripped from his hair.

The kitchen felt small as a confessional.

“You’ll catch your death,” I said, my voice softening without permission.

“Take off that shirt.”

He hesitated just long enough to remind us both the choice was not his.

“Yes, ma’am.” He pulled it over his head.

The marks on his back were old on old—thin spiderwebs, thick rope ridges.

None were ours.

We were good Christian owners, we told ourselves.

We did not beat our people.

We only bought the ones somebody else had already broken.

I lifted the towel.

My fingers brushed his skin.

It was like touching a live wire.

Something cold in me flared hot and furious and I snatched my hands back.

The towel slid down his arm.

He did not reach for it.

He stared at a place past my shoulder, jaw clenched.

I could have left.

I could have locked myself away and begged God to drown the moment in forgetfulness.

Instead, I picked up the towel again.

“Sit,” I told him, pointing to the chair by the stove.

“Martha will bring coffee.

I’ll—see to the rest.”

He sat.

The room shrank.

The storm outside dulled to the roar of blood in my ears.

I dried his shoulders, his neck, the back of his head—each pass another step down a staircase I could no longer pretend I was not descending.

When I came around, we were nearer than any mistress and enslaved man had a right to be.

His eyes—dark, steady, resigned—met mine without skidding.

There was fear there, and worse: expectation.

He had seen this before.

Not with me.

With others.

White women whose loneliness outpaced their fear of damnation.

White women who reached for the nearest body that could not say no.

“You don’t have to—” I began, and stopped.

We both knew that was a lie.

“Ma’am,” he said quietly, “I do what I’m told.”

The truth of it split me open.

I will not write the details of that night.

They are not the point of this confession.

What matters is this: I crossed the line.

I took a man whose body already belonged to too many hands and made it serve my loneliness.

I told myself I was not like those pale ladies on plantations who summoned boys and hushed them with jewelry and threats.

I told myself it was different because I felt guilty, because I prayed before and after, because I wept into my pillow when it was done.

The ledger of sin does not tally rationalizations.

It records only what is done.

Mornings after, I went about my duties with red eyes and sweeter manners than ever.

I visited the sick.

I sewed altar cloths.

I hosted prayer for the widows.

I stood beside my husband while he preached Joseph fleeing Potiphar’s wife.

No one saw my hands tremble.

Except the women who came to my parlor with their own tremors.

The first was Mrs.

Eliza Mayfield, widow.

Her husband had died under a fallen tree.

The casseroles and offers had dwindled.

Grief is heavy; people tire of holding it with you.

She was thirty-five.

Once called pretty, now called brave.

Her hair grayed at the temples.

Her mouth learned polite smiles.

Her hands trembled when her nights were too long.

“Is it wicked to miss touch?” she asked, eyes fixed on my embroidered scripture.

“Not any man in particular—just touch.”

I should have said yes.

I should have told her the Lord would be enough.

Instead, something in me soothed and sharpened by my own sin heard her words like a key turning a lock.

“There are ways to ease a body,” I said, choosing words like they might explode, “without endangering the soul the same way as ordinary sin.”

She stared.

“You cannot mean—”

“We are women,” I said.

“Men wrote the laws for themselves.

They do not count our needs.

They do not admit we feel them.”

“You’re saying,” she whispered, “that if a woman were to— with a colored man—it would not be counted the same?”

“I am saying,” I replied, “such a man has no rights to be injured in that way.

No covenant broken because there was no covenant with him to begin with.

It is”—I searched for a word—“a kind of labor.

Sorrow for one, relief for another.”

If such a thing were done, I added, it must be under secrecy, under guidance, so no one is harmed more than necessary.

“Have you known of such arrangements?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said, the word tasting like ash.

“I have known.”

From there, the steps unfolded like a hymn everyone already knows.

I was the pastor’s wife.

I controlled the schedules.

I knew when Josiah would be in the church, when the ladies gathered, when the men worked fields.

I had the authority to call Isaiah to the parsonage under pretense.

I had the trust of the women—they’d been taught my advice was godly.

I used that trust like a weapon.

Eliza came first, trembling, like a girl sneaking into a dance hall.

I led her not to my bedroom but to the small laundry room—the smell of lye and soap strong enough, I told myself, to wash away anything.

I spoke to Isaiah in the hall.

“There is something you can do to serve your mistress,” I said.

“You will not speak of it.

You will not deny it.

Remember: obedience keeps you alive.”

He looked at me with tired, hollow recognition.

“How many?” he asked quietly.

The word caught.

“How many what?”

“How many women,” he said.

“I seen this on other places.

Misses get lonely.

She share out a body that ain’t hers to share.

When she done she say it was all in my hands.”

Shame burned.

“There will be no others,” I lied.

“Only Sister Mayfield.

She is grieving.

Do what is required, then forget.”

His laughter was short and humorless.

“Yes, ma’am.

I’ll try.”

Eliza emerged undone and refastened—veil crooked, hair loose, shoulders looser.

She couldn’t meet my eyes.

She gripped my hands.

“God forgive me,” she whispered.

“Bless you.”

Bless me.

It should have ended there.

Sin rarely ends where we think it should.

The second woman: Caroline Weatherbe, twenty-eight.

Almost engaged three times; each match fell through for flimsy reasons.

The whisper turned: unmarriageable, too sharp, too plain, too much of something.

She came feigning harvest supper talk; conversation drifted to marriages and babies.

“I do not believe the Lord meant for me to be anyone’s wife,” she said to the window.

“I have never been the girl men choose.

I am the girl they practice conversation on.”

“There are other ways,” I heard myself say.

“For a woman to know she is wanted—even if no husband comes.”

She squinted—suspicion and curiosity.

“Spoken like a woman with a secret.

French novels? Or something worse?”

“A man in this town whose body answers as any man’s,” I said.

“Whose heart will not entangle with yours because it would cost him too much.

Men like—”

“Isaiah,” I said.

“He belongs to no white woman.

His services injure no husband’s claim.”

“That is monstrous,” she whispered.

“And yet… Do you truly believe a woman could— and still be free to marry a gentleman if the chance came?”

“Men count our purity by surface,” I said, voice low and bitter.

“They count blood, not truth.

They will only ask if you come untouched by scandal.

They will not ask what your heart endured.”

“I am tired,” she said after a long pause, “of being nothing but a vessel waiting to be chosen and never filled.”

“I can arrange a private hour,” I said.

“Under my roof.

Under my supervision.”

“You speak like a madam,” she said.

“And you speak like a woman taught her body is wicked for wanting anything,” I replied.

She came.

When she left, hair disordered, she did not thank me.

“It is done,” she muttered, as if crossing herself.

That night I lay awake listening for Isaiah’s steps.

I imagined him in the yard, tipping his head back to a sky with no stars.

The third was the youngest: Rebecca Tally, twenty-five, wife of a trader away more than home.

Two little boys like ducklings.

A laugh that sounded like a place with more water than our town.

She complained of her husband’s absences.

“He spends it all in New Orleans—cards and the women above the taverns.

Then comes home and expects me to smile.

He smells of perfume and whiskey and smoke and I am meant to be grateful.”

“Have you spoken of your hurt?” I asked.

“You know what men hear when a woman speaks of hurt? Nagging.

He calls me ‘little wife’ and pats my head.”

“How do you stand it?” she asked, looking at my neat, brittle world.

“I asked the Lord for a solution,” I said evenly.

“He did not send me a husband who cherished me.

He placed someone whose body could bear a portion of my burden.”

“Are you saying—?”

“I am saying,” I replied, “there is a man here with no claim on your heart, barred by his station from speaking of what passes, whose suffering has already been so great this duty will not be the thing that breaks him.”

Even as I said it, I heard the cruelty.

I dressed it in piety.

“If your husband spends nights in sin,” I added, “is it so wicked for you to find a moment’s comfort in a soul who will never boast of it? Is it not in a way—justice?”

“Justice,” she whispered.

“That is all I have prayed for.”

There is nothing so dangerous as a righteous word used to justify unrighteous acts.

She came.

The web tightened.

I no longer knew who was spider and who was caught.

Isaiah began to change.

He spoke less, moved like a shadow, flinched at sudden noise.

He woke at night shouting and bit it off.

Martha kneaded bread and muttered, “House heavy.

Heavier than it got right to be for such a little place.”

“It is the Lord’s house,” I snapped.

“What weight it carries, it carries for salvation.”

“You sure it the Lord’s weight,” she asked, pupils cloudy but sharp.

“Or somebody else’s?”

I turned away.

Anger feels safer than a blade between the ribs.

The weight showed itself in bodies.

Rebecca came white-faced.

“My courses are late—six weeks.” She darted a glance at my stomach.

Mine had never swelled.

The Lord had not given me children.

“Have you lain with your husband since his last trip?” I asked.

She shook her head.

“No, I could not.”

“Then there is your answer,” I said.

“It cannot be,” she whispered.

“How would such a child live? He would kill me.

Or kill him.”

We did not say Isaiah’s name.

We both saw his face between us.

“Sometimes the body sheds them as if they were never meant to be,” I said, the words poison.

“The Lord knows your heart.

He knows who placed you in this position.

He will not count against you what was forced upon you by a crooked world.”

It was a half-truth.

Half-truths cut deeper than lies.

She returned within a week—pale, walking gingerly.

“It is done,” she whispered.

“It happened in the night.

There was so much blood.”

I wanted to ask how.

Who helped.

What herbs.

I only drew her into an embrace that comforted neither of us.

Outside, Isaiah chopped wood.

Each swing was too hard, too fast.

“Do you know?” I asked.

“What happened with Sister Tally?”

His jaw tightened.

“I know she’d been sick.

We always hear things even when folks think we deaf.”

“She was with child,” I said.

The axe stopped midair.

“Not the first time a mistress find herself that way,” he said flatly.

“Not the last.”

“It was ended,” I said.

The axe dropped into dirt.

He stood breathing hard.

“That on me too, then? Add it to the list.”

“You speak as if you had a choice,” I snapped.

“You obey orders.

You are a servant.

You—”

“I am a man,” he said, turning, eyes blazing.

“Whether you say it or not.

A man forced to lay with women who cry and pray and then call it my doing when they can’t stand the weight of what they asked for.”

My hand flew before my mind.

The slap cracked the yard.

“How dare you?” I hissed.

“You think you suffer alone? You think you are the only one torn?”

He did not touch his cheek.

“Ain’t saying I know your pain,” he said.

“Just saying you don’t know all of mine.”

We stood, trading wounds with invisible chains between us.

“Get back to your work,” I said, voice brittle.

“And watch your tone.”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said to the woodpile.

“I’ll watch my tone.

Can’t say the same for my soul.”

The town buzzed.

Raised eyebrows.

Mrs.

Pruitt saw Rebecca leaving at odd hours.

Mrs.

Collins heard muffled voices near the parsonage late.

Deacon Harris, who heard trouble better than sermons, noticed Isaiah absent at odd times.

People who’ve known each other for years can smell a secret like rain.

One Sunday, after Josiah preached on keeping the temple pure, the congregation lingered.

Parasols bloomed; cigars lit beneath the cemetery oak.

I stood beside my husband, face composed, ears pricked.

“I swear,” Mrs.

Pruitt murmured to Mrs.

Collins, “I heard someone crying from the back of the parsonage Thursday night—not a child.

A woman.

Then I seen Sister Mayfield slip out before dawn.”

“Grief has many forms,” Mrs.

Collins said.

“Perhaps she could not sleep.”

“Grief don’t sound like that,” Mrs.

Pruitt sniffed.

“And that Rebecca—half the woman she was.

White as a sheet.

Her husband due next week.”

They glanced at me, then away.

Brushfire in dry grass.

If you had stood there—seen the widow’s red eyes, the unmarried daughter’s brittle laugh, the enslaved man’s hollow stare, the pastor’s wife smiling too perfectly—who would you have blamed? Don’t answer from the safety of the future.

Be honest with your heart now.

The brushfire did not become blaze all at once.

Before flames came smoke in the person of a young man from the district office.

Thomas Avery, twenty-four, freshly ordained, soft-faced and soft-handed.

A leather satchel, letters of introduction, a mandate to “observe and assist.” He stayed in our guest room.

He reviewed Josiah’s records—membership rolls, tithes, minutes.

He attended gatherings, pen scratching his little notebook, eyes on flock and shepherd alike.

He was almost reverent to me—pastor’s wives are half saints to very young ministers.

Three days in, he noticed Isaiah.

“Who is that?” he asked.

“I did not see his name on the rolls.”

“He is staff,” I said.

“Property of the church.

A bequest.”

“Ah,” Thomas frowned.

“We did not have such arrangements up north.”

“This is not the north,” I replied.

He watched Isaiah sweep, brow knit.

“You, Sister Whitlow,” he said, “have instituted quite a collection of women’s meetings.

Sewing circles, prayer, night vigils.”

“The women need space to bear one another’s burdens,” I said.

“Surely you do not object.”

“Not at all,” he said too quickly.

“It’s just—I’ve heard some speak of being here very late.

Without their husbands.

It is…unusual, isn’t it?”

“Women’s souls do not keep business hours, Brother Avery,” I smiled without teeth.

“Sometimes tears fall after midnight.

I am appointed to catch them.”

He nodded, chastened outwardly, but the question lodged.

He watched not only Josiah, but the women.

He noticed who came early, who stayed late.

He watched Isaiah’s comings and goings with a curiosity that made my palms sweat.

One evening on the porch, I overheard him tell Josiah, “Your attendance is steady.

Your sermons sound.

And yet there is a…tension I cannot name.

As if people look sideways.”

“This is a hard land,” Josiah sighed.

“Men break their backs.

Women bear too many children.

Everyone is one fever from ruin.

Tension is as normal as humidity.”

“Perhaps,” Thomas said.

“It’s just—sometimes the women look at the parsonage as if it is not only a house of prayer but of—” He stopped, blushing.

“Forgive me.”

It was too late to call the thought back.

I began to wake with my heart racing, convinced I heard footsteps in the hall or voices in the yard.

I dreamed the laundry room door swinging open to reveal a semicircle of faces: Eliza’s, Caroline’s, Rebecca’s, Isaiah’s, Brother Avery’s—each a facet of accusation.

I wrote more in my Bible margins than ever—underlined Confession.

Judgment.

Mercy.

Wrath.

Be sure your sin will find you out.

Though your sins be as scarlet… There is nothing covered that shall not be revealed.

I underlined them, then shut the book in terror.

The breaking point came with a fall.

A cool morning, first hint of autumn.

I had invited the widows for special prayer.

Eliza in black.

Two older women.

Caroline, late and flushed.

We knelt.

I led petitions—for the nation, church, children.

When I said husbands, Eliza’s shoulders shook.

When I said secret burdens, Caroline made a sound—half laugh, half choke.

Rebecca did not come.

Halfway through the second psalm, pounding rattled the door.

Martha rushed in—apron spattered dark.

“Miss—you got to come.

It’s Miss Becky.

She done fell in the yard ‘cross from the store.

Blood everywhere.”

We ran.

In the dusty patch between store and livery, a crowd.

Rebecca crumpled on her side, dress soaked from waist to knee in spreading red.

Eyes half open and seeing nothing.

Isaiah there, pressing a rag, his hands slick with blood.

“What happened?” I cried.

“She was just walking,” Deacon Harris panted.

“Dropped her basket.

Went down like she’d been shot.”

“Tell them it was the stairs,” Rebecca breathed against my ear.

“Tell them I fell.”

I knew what she meant.

She did not want them to know it was not the first time blood had come sudden and punishing.

“I will,” I lied.

“Promise me one thing,” she rasped.

“Don’t let them kill him.

For…for what I asked for.” Her gaze flicked to Isaiah.

I swallowed.

“I promise,” I lied again.

She died before the doctor arrived.

The town needed a cause.

No one wanted to say abortion aloud.

Too ugly.

Too close.

They reached for something they could hang outrage on without implicating themselves.

They found it in the color of Isaiah’s hands.

He had been there.

He had touched her.

Blood had gotten on him.

“What business you got touching a white woman like that?” one man snapped.

“Coulda waited for the doc.

Coulda let her husband—”

“She was dying,” Isaiah said quietly.

“Ain’t color in that.”

His calm inflamed them.

Whispers grew: too familiar, took liberties.

Perhaps she had been with child.

Perhaps it had been his.

No one spoke aloud how often her husband was away.

No one traced the line from their silence to her desperation.

It was easier to draw a line from her body to the man whose skin they already feared.

Josiah tried to quiet it.

“My flock will not devour itself,” he declaimed.

“We will not descend into lawless accusation.” But even as he spoke, his eyes slid toward Isaiah with doubt.

He had heard the whispers about the parsonage.

He had chosen not to believe.

The cost of that choice now pressed on him from all sides.

At supper, the parsonage felt like a room of ghosts.

Thomas sat stiff and pale.

Josiah pushed food.

Isaiah ate standing in the kitchen doorway, shoulders hunched.

I could not swallow.

“Something is wrong in this house,” Thomas said, conviction bright and cold.

“This is not your concern,” I snapped.

“You are a guest.

You have seen fragments.”

“Fragments are sometimes enough,” he said.

“Enough to know there is a pattern.”

“You are out of line, son,” Josiah said.

“Perhaps,” Thomas replied.

“I was sent to guard the flock.

I cannot shake the sense a wolf has gotten in.” His eyes fell to Isaiah.

“Do not look at him,” I said too loud.

“He has done nothing but serve faithfully.”

“How can you be sure?” Thomas asked softly.

“Have you been with him every hour?”

“Yes,” I said.

The word leapt before I could stop it.

“So you admit it,” he whispered.

It was too late to snatch the word back.

—

The denomination moved faster than shame.

Within a week, a letter: the regional superintendent would hold an inquiry “to preserve the integrity of the Lord’s house.”

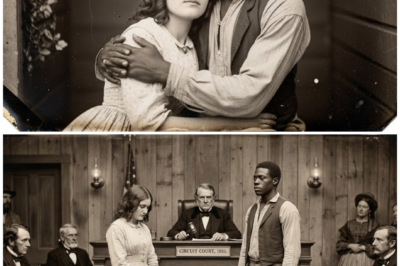

It took place in the sanctuary on a gray afternoon.

Pews crowded with stiff faces.

The superintendent, stern, with a voice like an iron kettle, sat up front with Josiah and two deacons.

Brother Avery hovered, notebook ready.

One by one they called people.

Eliza, hands twisting: “Nothing I know.” Caroline, jaw set: “I will not be your hound.

I will confess to the Lord alone.”

Finally they called Isaiah.

He walked the aisle like a man descending to a trap door.

“State your name.”

“Isaiah.”

“Surname?”

“Ain’t had use for one in a long while, sir.”

“You are property of this church?”

“Yes, sir.”

“You have been observed in the company of several white women under irregular circumstances.

What do you have to say for yourself?”

He could have saved himself by throwing us to wolves.

He did not.

“I do what I’m told,” he said.

“Always have.

Folks tell me haul wood, I haul wood.

Fix a roof, I fix it.

Go to this room or that room, I go.

Keep quiet, I keep quiet.”

“That is an evasion,” the superintendent snapped.

“Have you engaged in fornication with women of this congregation?”

Isaiah’s eyes flicked to mine.

Then up to the ceiling’s peeling paint.

“Sir—with respect—that a yes or no question for a man who had a choice.

I ain’t never had that, so I don’t know how to answer you right.”

“We will take your silence as admission,” the superintendent said, turning to Josiah.

“Your household has not been guarded.

This man must be removed.

Sold at minimum.

Perhaps worse.”

“Not solely about him,” Thomas burst out.

“There are larger issues—patterns.

The pastor’s wife—”

“Brother Avery,” the superintendent cut him off.

“You will wait your turn.”

Eyes swung to me anyway.

I stood.

“I would like to speak,” I said.

“No one has accused you formally,” the superintendent said.

“It is about all of us,” I said.

“High time someone said so plainly.”

I walked up the aisle.

With each step, I stripped another layer of the persona I’d stitched for years.

At the front, I turned to our world.

“I have sinned,” I said.

The words rang off rafters.

“Not in a vague way you can tuck into a prayer.

Specifically.

Terribly.

Months ago, I crossed a line with Isaiah.

Not once.

Many times.

I took comfort in his body because my marriage bed was cold.

I told myself it was my right.

I told myself it was less of a sin because he was already a man deprived of rights.”

Gasps.

Prayers.

Tears.

“I did not stop there,” I went on, throat tight.

“I used the trust you placed in me to draw other women into the same sin.

I told them it was a way to ease loneliness without breaking vows.

I dressed hell up in Bible verses and offered it as medicine.”

Eliza crumpled.

Caroline’s eyes flamed—horror and a terrible kind of relief that I had not left her alone in the dark.

“I do not say this to exonerate him,” I said.

“He is not innocent.

None of us are.

But if you are sharpening knives to cut someone out of this body, let them first fall on the neck that led others to slaughter.”

I looked at my husband.

He seemed smaller than I had ever seen him.

“You once preached the church as a bride ready for her groom,” I said softly.

“I have soiled my gown.

And I know I did not tear it alone.

This town tugged at the hem—every woman taught her only worth is her chastity and womb; every man taught he may own another man’s body because law says so; every sermon that named sins of the flesh while ignoring sins of the whip.”

“My wife,” Josiah whispered—pain and disbelief wrestling.

“I am still that,” I said.

“Whether you claim me or not.

But I will not hide behind the title.”

The superintendent pounded order back into his voice.

“Confession does not erase consequences.

We must act to restore order.

The enslaved man must be sold immediately.

As for you, Sister Whitlow—”

“You will do as you must,” I said.

“I ask one thing.”

“What?”

“Do not call this one woman’s fall.

Do not tuck it into a report as unfortunate aberration.

Name it what it is: fruit of a rotten tree.

The tree that says some bodies are tools for others’ salvation or pleasure.

The tree that has stood in the yard of this church since the first slave ship docked.”

“You speak dangerously,” he recoiled.

“Almost as if you question the institution itself.

Slavery is sanctioned by scripture—properly understood.”

“So is confession,” I said.

“So is repentance.

You like one half.

Not the other.”

They sold Isaiah within a week.

A trader came with a wagon and a printed bill of sale.

I watched from the kitchen as he climbed into the back—hands unbound, future shackled.

He did not look at the parsonage.

He looked at the church and the crooked steeple and the graveyard where stones said nothing of lives lived above them.

“Where they took him?” Martha asked.

“South,” I said.

“Louisiana, the man said.”

“Further down into the river,” she murmured.

“That where the deep water is.”

Something in me left with that wagon—something both cancer and companion.

They did not sell me.

They did something worse.

They left me in place and stripped everything that had once given the place meaning.

Forbidden to lead women.

Forbidden to teach children.

Forbidden to be anything but a shadow while a younger pastor’s wife took my chair at gatherings.

We did not move away.

Josiah said it was his duty to stay and rebuild.

Whether he stayed out of stubbornness, pride, or penance, I cannot say.

The women avoided my eyes—some out of disgust, some out of fear that proximity might stain them.

Only Eliza sometimes left a small bundle on my back step—bread, little cakes.

An acknowledgement of shared blame.

Caroline married two years later—a widower from another county.

She looked radiant and haunted.

As she passed, her fingers brushed my pew—blessing and accusation.

Rebecca had no such future.

Her boys grew without hearing the full story of why their mother died clutching my sleeve.

I wrote this in dim small hours while the town slept.

I had no priest to hand it to.

I wrote not to be absolved—you cannot do that for me—but so you would see clearly what sin looks like when it dresses in Sunday clothes.

I used an enslaved man as if he were not a man.

I encouraged other women to do the same.

I let my loneliness blind me to his terror.

I let their needs drown his right to be left untouched.

I used the language of faith to sanctify my desire.

If you look for a monster in this story, you will find many.

My face is one.

But the deeper horror is that none of this required supernatural evil—only ordinary people in an ordinary town in an ordinary year, living according to rules they were handed, and choosing, again and again, not to question those rules when they served their comfort.

If I have any plea, it is this: Do not bury my words and say, “How terrible they were back then.” Ask instead: Where do we still use someone else’s body to fix our pain? Where do we still press the vulnerable into the cracks of our crumbling selves and call it necessity?

Your clothes are different.

Your laws have changed.

Your heart is the same trembling, hungry clay as mine was.

If stories like mine make that clay burn—if they open your eyes to the quiet ways power and piety twist—do not let the feeling fade when the telling ends.

Stay with it.

Share it.

And if you want to keep turning over the stones they told you never to touch, to hear more of these buried truths hauled into light, mark your presence so the teller knows they’re not speaking into a void.

Say which moment will be hardest to forget.

Not for me.

For you.

I do not know this side of judgment whether the Lord has forgiven me.

I only know I could not rest until I spoke plainly.

My name is Sarah Anne Whitlow.

I was the pastor’s wife.

And this is what I did.

News

The Plantation Lady Who Locked Her Husband with the Slaves — The Revenge That Ended the Carters

The night I decided my husband would go to sleep on a slave’s pallet, the air over Carter Plantation felt…

The Paralyzed Heiress Given To The Literate Slave—Their Pact Shamed The Entire County, Virginia 1853

On the night the county gathered to watch a girl be given away like broken furniture, the air over Ravenswood…

The Judge’s Daughter Who Secretly Married Her Father’s Favorite Slave—The Trial That Followed, 1851

They said the courthouse had never held so many people. The air felt like wet wool—heavy with perfume, sweat, and…

The Plantation Lady Replaced Her Husband’s Heir With the Cook’s Slave Child—Georgia’s Silent Scandal

They say the storm that broke over Merryweather Plantation in the spring of 1854 was the worst anyone in that…

The Mistress Who Promised Freedom To The Slave Who Impregnated Her First—She Lied Twice

The first time I saw Helena Ward’s handwriting, it was bleeding through a ledger that should have held nothing more…

The 18-Year-Old Slave Boy Who Impregnated the Governor’s Wife — Virginia 1843

On the night Virginia decided what kind of child it would let a governor’s wife carry, I was still just…

End of content

No more pages to load