On the night the county gathered to watch a girl be given away like broken furniture, the air over Ravenswood hung so thick with heat and tobacco smoke that even the crickets seemed to hold their breath.

Carriages lined the long drive; lamps swung; wheels crushed white gravel.

Inside, the grand parlor’s tall windows sweated behind heavy red drapes.

Men in linen coats and women in lace sat in rows like a jury, fans fluttering like pale moths.

They came because no invitation is more irresistible than humiliation dressed as charity.

Under General Jonas Whitfield’s gilded portrait—hero of a half-remembered war, painted eyes pitiless—a wheelchair had been parked with the precision of a display piece.

Eleanor Whitfield sat in it, back rigid, hands folded so tightly in her lap her knuckles bleached against ivory silk.

Pale blue—her aunt’s choice—the color of a sky she hadn’t seen in months.

It fell beautifully over useless legs, masking the narrowness and the inward droop of feet like a doll left in rain.

She kept her chin high.

If they were going to stare, let them strain their necks.

Samuel Whitfield stood beside her.

Years had not softened him; they had sharpened what was hard.

Steel gray crept his temples.

Sweat shone at his collar despite a fan dragging hot air in circles.

“Neighbors, friends,” he began, voice carrying with the practiced ease of a man who expects to be heard.

“You have been kind enough to come tonight as witnesses.”

Eyes slid over Eleanor—quick, furtive, a mix of pity and gossip hunger.

The broken Whitfield girl.

The one who once rode sidesaddle like an Amazon and now couldn’t move her toes.

“You know of the misfortune that befell my daughter two years past,” Samuel said.

“The accident, the doctors, the limitations placed upon her prospects.

You know our standing in this county.

I do not shrink from responsibility, however unpleasant.”

A polite murmur rippled.

Eleanor stared at a plaster crack above the portrait and tried not to hear the words she’d been fed in fragments for two years—behind doors that never accounted for old wood’s acoustics.

She’s useless now.

Who would marry a woman who can’t walk to her altar? Better send her away.

“Tonight,” her father went on, “I take an unusual but necessary step.

My daughter requires constant care—more than the women of the house can provide, more than is proper to ask a physician.

She requires a companion who can read, write, attend day and night.”

He nodded toward the servants along the wall.

“Bring him forward.”

A stillness, then parted linen and a tall figure stepped into lamplight: dark skin, simple shirt and trousers, bareheaded.

Light caught the planes of his face, the straight nose, the full mouth pressed to a line.

Broad-shouldered, not bulky.

There was an economy to his movements that spoke of long practice at taking up as little space as possible.

His name—Eleanor knew—was Isaac.

Glimpses: beneath her window carrying ledgers; a reflection in polished wood bearing papers to Samuel’s study.

Always in motion.

Always quiet.

The county knew more: the strange one, the dangerous one—the slave allowed letters and numbers, who balanced accounts, read contracts and lawyers’ tight script.

Some whispered he read newspapers, tracts—abolitionist pamphlets wrapped in northern cloth.

A literate slave is a loaded gun kept on the mantle.

Samuel waved it before his friends and smiled.

“This man,” he said, hand resting on Isaac’s shoulder like presenting a prize animal, “has proved useful in keeping books and handling correspondence.

He shows a facility with letters rare in his station.

In recognition of his skills, he will be promoted.”

Polite chuckles.

A cough behind a fan.

Isaac’s gaze fixed a foot above the carpet—emptied by practice.

Eleanor wondered what it felt like to be touched, unasked, like polished wood at sale.

“He will live in my daughter’s rooms,” Samuel announced.

The words fell like stones into still water.

Fans stilled.

A glass clicked a nervous tooth.

Some fool whistled—a sound strangled by a wife’s elbow.

Eleanor did not look at Isaac.

Heat rose in her cheeks.

Her body was still.

Inside, everything thrashed like a trapped animal.

“My daughter is a Whitfield,” Samuel said, as if settling everything.

“She will not be hidden.

She remains mistress of this house, and this arrangement ensures her comfort and dignity.” He added, pleased with his symmetry, “It ensures the talents of this slave are used to highest purpose, not wasted in dirt.

You see—even misfortune can be arranged to serve order.”

Order hung in the air, heavier than smoke.

Isaac’s presence arrived beside her as if conjured.

He had crossed the rug without sound.

He stood a careful distance from her chair, as if invisible lines were marked on the floor.

“Eleanor,” her father said, wearing a public mask of concern, “you will acknowledge your attendant.”

She turned her head slowly, as if its weight were a burden, and met Isaac’s gaze.

She expected fear, deference, the dull emptiness she had seen in the enslaved who drifted like furniture.

Instead: a deep, steady awake-ness.

Quick assessing intelligence—gleam of a knife beneath cloth.

He did not challenge.

He did not flinch.

He looked at her the way one trapped being looks at another, realizing the bars differ but the cage is the same.

“Good evening, Miss Eleanor,” he said softly—words shaped with the care of someone beaten for speaking poorly.

No tremor.

She held his look a fraction longer than was proper, then inclined her head an inch.

“Welcome to my prison, Isaac,” she said, mouth barely shifting.

A few ladies tittered—taking it as a poor invalid’s joke.

Only Isaac’s eyes told her he had heard what it truly was.

After the guests floated away in carriages trailing whispers like smoke, Eleanor sat propped in bed while Clara, her maid, unpinned her hair.

Lavender and stale air lingered.

Windows open—the night pressed heat through curtains.

“He’s in the little room next door now,” Clara murmured.

“They put a pallet and a table there.

Said he’s to be here all the time.”

“So I’ve been told,” Eleanor replied.

Clara hesitated.

“Miss, you want I should stay? Tell Mr.

Samuel you had a turn—”

“No,” Eleanor said, more sharply than she meant.

Softer: “No.

That will only make him more determined to drive the point home.”

“It ain’t right,” Clara muttered.

“Putting a man in a lady’s chambers ain’t right for neither of you.”

“Clara,” Eleanor said, eyes closing, “nothing about my life has been right for some time.”

After candles burned low, a soft knock at the door to the small adjoining room.

“Miss Eleanor?” Isaac—careful.

“Come in,” she said.

Darkness moved deeper.

He did not light a candle at first—she appreciated that.

It felt, briefly, like not being observed.

“I am to ask if you require anything more for the night,” he said.

“Your father wishes a note of your needs.”

“My father wished an audience,” she replied.

“He has had it.”

Silence.

Then, unexpectedly: “It was a cruel sort of audience,” Isaac said quietly.

“If you’ll pardon me.”

“You are bold,” she said.

“I am already in your room, miss,” he replied.

“Not much further for boldness to go.”

A breath escaped her—almost a laugh.

“Do you disapprove of this arrangement?”

“I have no right to approve or disapprove,” he said.

“I am told where to stand and stand there.

Told where to sleep and sleep there.

Now I am told to be here.” He struck flint.

Candle flared—his cheekbones hollowed by light, eyes glinting.

“But I understand an audience built for other people’s amusement,” he added.

“We in the quarters know something of that.”

“I am to read to you tomorrow,” he said, moving no closer than the candle table.

“From letters or whatever you wish.

Shall I bring something particular from the library?”

“The ledgers,” she said impulsively.

“The ones he keeps locked beneath his desk.”

“That is not light reading.”

“No,” she said.

“I find I have an excess of time.”

“If the keys are given to me,” Isaac said, “I will bring them.”

His gaze flicked once to her motionless legs, then away—as if obeying an internal rule against staring.

“Good night, Miss Eleanor.”

“Good night, Isaac.”

When the door clicked shut, darkness closed again.

She stared into it—remembered the horse’s scream, the sky canted, vertebrae cracking.

Samuel’s tight-lipped face by her bed.

The first time she tried to move her toes and found nothing answered.

On the other side of a thin wall, a man not allowed to own his own name slept on a pallet because Samuel had decided the best use of them both would be to offend an entire county.

“If they intend me to be an object lesson,” she thought, “then it’s only fair I learn the lesson thoroughly.”

In the morning, the sound of paper.

Quiet muttering.

Isaac sat by the window, ledgers stacked beside him, one open across his lap.

A pencil.

A scrap crowded with figures and small marks.

He was so absorbed Eleanor watched a moment before speaking.

“Good morning.”

He startled slightly, closed the ledger, rose at once.

“Good morning, Miss Eleanor.

Beg pardon.”

“How long?”

“Since shortly after dawn.

Your father sent for me—wished these figures checked.

The last harvest and spring’s sales.”

“So your work now is done in my room,” she said.

“Efficient.

He has consolidated both his embarrassments.”

A ghost of a smile crossed the corner of his mouth.

“I brought what you asked.”

“Read,” she said.

“Let’s hear what General Whitfield’s portrait presides over.”

He pulled a table close, opened a ledger, placed a ribbon.

Ink-dense pages, names, numbers, dates.

“Here.

The account for the year of your birth.”

“How poetic,” she murmured.

“Begin.”

His voice was low, steady.

January 5: purchase of three male hands from Charleston, ages eighteen and twenty, $1,200.

January 17: sale of one female, age fifteen, to Hargrove, $450.

February 6: payment to sheriff for retrieval of runaway property…

Cold words.

Warm lives flattened to lines.

Children listed as “issue.”

“What do those marks mean?” she asked of his marginal symbols.

“Merely my way of keeping track.”

“Of what?”

He weighed.

“Patterns.

Of who lives and who does not.

Of where the money comes from and where it goes.

Whose sins heap up faster than others.”

“You have been watching.”

“It is hard not to, when one’s hand holds the pen,” he said.

“How much do you remember?”

“Enough.”

“I want more than enough,” she said.

“I want what you see.”

“I must be careful,” he murmured.

“Words can be whips in the wrong ears.”

“They already are whips in your hands,” she said.

“Why not let them strike in another direction for once?”

He studied her.

“Have you ever wondered,” he asked, “why your father did not sell me away?”

“Has he had cause?”

“Year the cotton failed,” Isaac said.

“Year two overseers were found in ditches.

There have been whispers.

There have been moments he looked at me like he meant to send me south—or worse.

And yet—” He tapped pages.

“My hand knows too many of his lies.

My head remembers numbers better than paper.

As he once said: too useful to kill, too dangerous to trust.”

He said it in Samuel’s drawl; Eleanor’s stomach twisted at the accuracy.

“So you keep his secrets,” she said.

“I record what I’m ordered.

That is not guarding willingly,” he said.

“That,” she said, “is where we may no longer differ.”

Their days took shape.

Morning: ledgers and letters.

Isaac read.

Eleanor listened.

She learned his shorthand: a cross for death—fields, flogging, “discipline.” A circle for a child removed—sold to “another county,” “otherwise disposed.” Clara brought broth and glared.

“You ain’t got to listen to that ugly stuff.

Words like that catch fire.”

“That is the idea,” Eleanor said.

Afternoons: practical humiliations transformed by his professional care—shifting to avoid bedsores, adjusting braces, lifting with gentleness that had seen more broken bodies than hers.

“What did they beat you for?” she asked one evening.

“Too many things to name.”

“Name one.”

“For reading the Bible to my mother.

For correcting a figure in your father’s sums.

For not lying when I was expected to.”

“You were beaten for telling truth and for staying silent,” she said.

“Efficient.”

“The lash don’t care for consistency,” he replied.

Then: “I care that the ones who bleed aren’t the ones who profit.

And I care no one writes that down but in ink and numbers.”

“Then we shall write something else,” she said.

“You and I.”

He began to bring scraps: an overseer’s toll listing wagons and chained bodies; a copied paragraph from a neighbor’s account book; a northern newspaper salvaged from a stove.

He spread them like puzzle pieces.

“Look,” he said.

“Hargrove’s purchase of three mixed-race youths.

Three months earlier, your father’s ‘surplus issue.’ Same ages.

Same sums.”

“So our profit is their torn families,” she said.

“That is often the case.”

“And this,” she pointed, “$300 to Reverend Luther for a bell.”

“Cross with Galloway: $300 for ‘missionary work,’” Isaac said.

“And Galloway’s entry: sale of one girl to a passing trader—$300.”

“He sold a child to buy a bell,” Eleanor whispered.

“And wrote it as ‘missionary work,’” Isaac said.

“How long have you…” She couldn’t finish.

“Long enough to keep my mind straight,” he said.

“Now—perhaps for the reason sitting in this room.”

“If I asked you to gather as much as you could,” she said, “to compile a record not of profit but of sin—could you?”

“I could,” he said.

“At great risk.”

“I risk much by existing,” she said.

“Perhaps it is time the risk purchased something.”

“White folks think bravery is standing in a field with a gun,” he said, half-chuckling.

“You mean to sit in a bed with a pen and burn a county down?”

“If it burns,” she said, “it is because it’s tinder.”

One night thunder rumbled; the air tasted metallic.

Eleanor lay awake thinking of faces whose prices she now knew.

She wished for ears beyond Ravenswood, beyond Virginia.

“If you were here,” she thought toward a future she could not name, “what would you do? Look away, or stand beside a paralyzed woman and an enslaved man and say: this is wrong?” She imagined her voice slipping beyond the walls.

If you have an answer, hold it.

In another world, you might speak it aloud.

Weeks passed.

Isaac grew bolder: a jailer’s list of men detained for “uprising”; the northern paper, a miracle that “the fire had to wait” for.

They spoke less of they and more of we.

Then he found the old ledger: cracked leather, yellowed pages, “Private Register J.

Whitfield” across the top.

Entries less neat, more personal.

January 1815: bought carriage.

Mary confined—expecting child.

August 1831: “Jonas’s brother Samuel visited.

We discussed the matter of the boy born to Martha—barely a shade darker than my kin.

Resolved not to list him among the quarter.

Marked as private asset for now, named Isaac.”

“We are both Whitfields by their reckoning,” Eleanor said, voice thin.

“One raised above the staircase, one below.”

“Yes,” he said.

“I was born enslaved by my own blood.”

“Then this does not change what we are doing,” she said, resolve hardening.

“If anything, our knife is sharper.

Not only a master’s sins—we hold a man who mangled his own family to fit his power.”

“You would use this?”

“If every other proof is torn, we can always speak this,” she said.

“Even men who can endure a whipping of conscience over strangers will choke on a Whitfield carving up his own blood like a joint of meat.”

“You are not as broken as they imagine,” Isaac murmured.

“I am broken in the wrong places for their liking,” she said.

“My spine won’t carry me down an aisle; my womb won’t bring them an heir.

But my tongue works.

My mind works.

So does my appetite for retribution.”

The county’s first tremor came as a trial.

A scrap found beneath a bunk at Hargrove’s—careful, uneven hand: We as men, not cattle.

We bleed same.

Burn same.

One day the book will open.

The overseer recognized letters; the sheriff smelled “insurrection.” Judge Hallcroft called a public hearing.

“We will make an example.”

Rumor spilled like lamp oil.

Eleanor heard it from Clara.

“Three men,” Clara said.

“Dangerous papers.”

“Papers?” Eleanor’s pulse quickened.

“They say.

Trial’s in two days.”

“Fetch Isaac,” Eleanor ordered.

He already knew.

“Your father’s been summoned,” he said.

“They asked he bring ‘that literate slave’ to read.”

“Of course.

They need you to untangle their mess.”

“This is a rope waiting for my neck,” he said.

“The rope has always been waiting,” she replied.

“At least choose how it’s used.”

“What are you suggesting?”

She told him—reckless, dangerous, reliant on timing and nerve.

As she spoke, something changed in him.

The ember flared.

“You would have me read more than they give me,” he said.

“Open a book they did not bring.”

“Yes,” she said.

“You will bring it in your head and your hand.

I will bring my name.”

“If it goes wrong, they will cut my tongue out before hanging me.”

“Then let enough escape that the effort is wasted,” she said.

“Isaac…are you with me?”

“I thought I was chained to your misfortune,” he said.

“I see now I was lashed to my deliverance.

Yes.”

The courthouse steps were crowded under a sky scrubbed hard and blue.

Isaac lifted Eleanor from the carriage—careful as always—under a hundred eyes.

Whispers hissed.

He set her near the front.

Samuel glared.

Isaac took his place by the clerk’s table.

Judge Hallcroft banged the gavel.

“We are convened to hear the matter of three negro men accused of fermenting insurrection through written materials and unauthorized discourse.

The peace of this county depends upon clear judgment.”

“The peace,” Eleanor thought.

“Bought with others’ silence.”

The sheriff held a crumple of paper.

“Found under a bunk,” he said.

“Read it.”

Isaac took it.

“It says the writer believes he and his fellows are men, not cattle,” he read.

“That they bleed and burn the same.

That one day the book will open and the Lord will see who is on which side.”

“And what do you think it means?” the judge demanded.

“I think it means the one who wrote it has eyes,” Isaac said.

“And has seen something that troubles him.”

“You will confine yourself to reading,” the judge snapped.

“Yes, sir.” Isaac folded the scrap, set it down.

“Is there more?”

“There is always more,” he said.

He reached beneath the table, lifted a ledger, opened it.

“What is that?” the judge snapped.

“A record of this county’s dealings,” Isaac said.

“Of who bought and sold, beat and killed in the name of profit and order.

You are worried about a scrap under a bunk.

Perhaps consider the mountain it sits on.”

“Enough!” the judge barked.

“With respect,” Isaac said, voice carrying, “you called me to read.

I am reading.”

He read names.

Dates.

Prices.

He read the bell bought with a child.

The sheriff paid to swallow a drowning.

Transfers of “mixed-race” children under false names.

The “accidents” recorded as discipline.

Debts covered with flesh.

“You lie!” someone shouted.

Isaac turned a page.

“Entry: Samuel Whitfield—surplus issue to Hargrove.

Three children not listed by name.

Same week—Hargrove purchase of three mixed-race youths.”

Samuel surged.

“Outrageous! I will not stand—”

“You have been standing on this,” Isaac said, looking him in the eye.

Deputies lunged.

The judge shouted.

Isaac wrenched free enough to cry, “And this: Entry—Jonas Whitfield—private asset.

Boy born to house girl Martha—too pale for the quarters.

Marked as not to be listed.

Named Isaac.”

The room froze.

Samuel’s face went paper-white.

“Lies,” he spat.

“Check the hand,” Isaac said as they forced him to his knees.

“The ink is older than I am.

The truth has been there longer than your denial.”

Eleanor pushed herself forward.

“Your honor—may I speak?”

“Miss Whitfield,” the judge sputtered.

“This is not—”

“I am Eleanor Whitfield,” she said, voice precise, cutting.

“Daughter of Samuel.

Heiress of Ravenswood.

I attest to the ledger’s existence.

I have seen it.

The hand is genuine.”

“Eleanor,” Samuel hissed, stunned.

“You do not know what you’re saying.”

“I know exactly,” she said.

“Two years told I know nothing.

I’ve had time to learn.”

“You can call this sedition,” she said to the room.

“Madness.

The ravings of a paralyzed girl and a half-blood slave.

The ink does not care what you call it.

The ink tells the same story no matter who hears.”

Shock.

Denial.

A few reluctant flickers of recognition.

“They stand accused of dreaming of being men,” she said of the chained three.

“Is that a crime?”

“It is when it leads to unrest,” someone snarled.

“Then perhaps the unrest lies not in their words, but in your conscience,” she answered.

Noise surged.

Hallcroft cracked the gavel until the wood split.

“Recess.

The accused back to cells.

The slave Isaac remanded to the sheriff.

Miss Whitfield—home.”

But the words were out.

They hung like smoke long after the room emptied.

Ravenswood became a fortress.

Samuel locked himself in his study; notes went out like darts.

Some men were called to “speak privately.” Others were accused of spreading rumors.

Eleanor was penned upstairs under a cousin’s continuous watch.

Isaac was chained beneath the smokehouse, to be “dealt with when matters cooled.”

They didn’t.

Stories slipped through cracks as they do.

Great houses told themselves a crippled girl was led astray by a cunning slave.

The quarters told each other one of their own had stood in a white court and read the county’s sins with a white lady beside him.

Whispers crossed county lines.

A peddler mentioned a ledger opened in court.

A free black preacher received anonymized copies.

A northern paper received documents with a note: These are the true books of our county.

The account is not yet settled.

“You’ve put your father in a terrible position,” the cousin sniffed one day, spooning broth.

“They are worried about their names,” Eleanor said.

“Not about me.”

“You sound like that slave.”

“Thank you,” she said.

One night, Clara slipped in, eyes wide.

“They’re going to do it.

Tonight,” she whispered.

“Your father and the sheriff.

Take him out, say he tried to run, hang him quiet.”

“No,” Eleanor breathed.

“They will,” Clara said.

“Unless…”

“Unless?”

“You write,” Clara said.

“Everything you know.

In your fine hand.

Sign your name.

We’ll get it out.

If he dies, the ledger in his head goes with him.

The ledger in your hand doesn’t have to.”

“Bring ink,” Eleanor said.

“And paper.”

Her hand cramped.

Back burned.

Sweat slicked her temples.

She wrote of entries and bells and drownings and “private asset Isaac.” She wrote of the trial.

Of chains.

Of the men who stood straighter.

Of ink’s neutrality and conscience’s unrest.

When she finished, her hand shook so badly she could scarcely lay the pen aside.

Clara wrapped the pages like glass.

“I know someone goes north,” she said—“in the seams of his coat.”

“Go.”

That night some swore they heard a horse panic, a rope, voices at the edge of the woods.

Some swore Isaac vanished like smoke.

One woman swore she saw a tall man at dawn, walking north with a stick and a bundle and a look like someone who had stepped off the page he’d been written on.

What Eleanor knew: a week later a northern paper printed an anonymous “Lady of Virginia” laying out in columns the commerce of souls.

Attached: copied entries that matched private accounts of the county’s “pillars.” No names, but enough dates and sums that those men recognized themselves.

Bankers in Richmond looked harder at Livingston County loans.

A preacher in another town preached about bells bought dearer than we know.

Some families slunk away; others doubled down, louder.

At Ravenswood, Samuel grew rigid and silent.

He rarely spoke to Eleanor.

Her body did not improve.

Pain rippled her spine like fire ants.

Nights she dreamed of running and woke with tears on her pillow.

But her world had widened.

Clara brought back clippings: mentions of a certain Virginia county “where accounting has taken a troubling turn.” Shame, Eleanor realized, is a kind of justice—not enough, but something.

A crack across a facade.

On quiet evenings she sat near the window, letting night air wash her face, thinking of Isaac—dead perhaps, feeding a tree’s roots; or alive, walking, back unbent, hands ink-stained by his own story.

In either imagining, their pact held.

He gave his knowledge.

She gave her name.

Together they shamed a county drunk on its own righteousness.

If this tale has found you across distance and years, and stirred in you that uneasy mix of anger and sorrow and recognition—if you find yourself thinking of these ledgers and voices pressed flat between paper and time—then keep them alive in your own words.

Talk.

Remember.

Refuse the silence that settles as soon as truth cracks through.

Eleanor Whitfield died some years later.

Newspapers did not note it.

No public mourning, save perfunctory notices to the easily offended.

To the official record she was a minor figure: a daughter who never married, an invalid who left no heir.

But beneath her bed, Clara found a stack of pages tied with string.

On top, in Eleanor’s clear slanting hand: The True Accounts of Our County, as Seen from a Chair.

Clara held them a long time, wrapped them in cloth, and gave them to a man heading north.

Years later, in a different town, a grandchild found them in an attic trunk.

An old man read aloud.

“This is not a ghost story,” he told the child.

“But it is a haunting—not of spirits, but of truths.

Written by a woman who could not walk but saw far, and by a man born in chains who carried keys in his head.”

Somewhere beyond that, someone else—under a flickering screen instead of a candle—listened and felt the same stirring.

The paralyzed heiress and the literate slave would never know those names.

But their pact—sealed in ink and risk and shame—kept echoing.

Long after ledgers of profit crumbled to dust, their quieter ledger of truth remained, waiting to be read aloud, again and again, as long as there were voices willing to form the words and ears willing to hear.

News

The Judge’s Daughter Who Secretly Married Her Father’s Favorite Slave—The Trial That Followed, 1851

They said the courthouse had never held so many people. The air felt like wet wool—heavy with perfume, sweat, and…

The Plantation Lady Replaced Her Husband’s Heir With the Cook’s Slave Child—Georgia’s Silent Scandal

They say the storm that broke over Merryweather Plantation in the spring of 1854 was the worst anyone in that…

The Mistress Who Promised Freedom To The Slave Who Impregnated Her First—She Lied Twice

The first time I saw Helena Ward’s handwriting, it was bleeding through a ledger that should have held nothing more…

The 18-Year-Old Slave Boy Who Impregnated the Governor’s Wife — Virginia 1843

On the night Virginia decided what kind of child it would let a governor’s wife carry, I was still just…

The 7’4 Slave Giant Who Broke 11 Overseers’ Spines Before Turning 22

They say it was the sound that damned him. Not the height—though he stood a full head above any man…

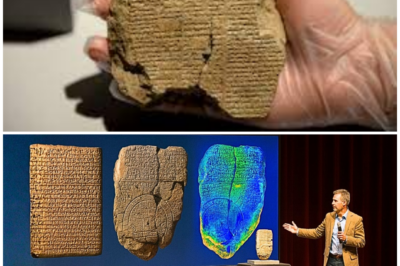

🔥 “They Wrote About Something That Shouldn’t Have Existed Yet…”: Newly Unearthed Sumerian Records Shock the World With Alleged Descriptions of Technology, Sky-Beings, and Events Thousands of Years Ahead of Their Time—A Revelation So Disruptive It Threatens to Rewrite Humanity’s Origin Story and Challenge Every Assumption We Thought Was Untouchable 😱

From the moment archaeologists pried the first cuneiform tablets out of the dust of southern Iraq in the late 1800s,…

End of content

No more pages to load