In April of 1831, seven wives of sugar planters in Matanzas, Cuba, killed their husbands within the same breathless, bitter week.

When colonial authorities investigated, they discovered one point of convergence: a mulatto slave of incomparable beauty named Sebastián Valdés, a cane-field worker whose magnetism seemed to defy every racial and social barrier of the day.

What truly happened between Sebastián and these women? How did a man with no legal power transform elite colonial wives into killers willing to risk everything? The answer winds through a world of sugar wealth and terror, careful seduction, and a slow, deliberate plan to topple the order from within.

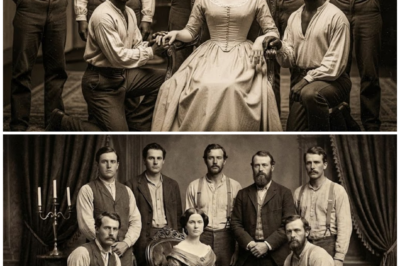

Matanzas, the “Athens of Cuba,” wore culture like silk.

Under the gleam of salons, theaters, and concerts, the valley was powered by a hidden, grinding engine: cane fields stretching for miles; mills that ran without sleep; barracks packed with bodies; and a math of death disguised as prosperity.

In 1831, roughly 40,000 people lived in and around the city—about 25,000 of them enslaved.

Two slaves for every white person.

That ratio fed a permanent terror among planters who feared the Haitian shadow—a revolt that would sweep them from the earth.

Sugar mills were machines for chewing up lives.

A cane-cutter’s hope of life after arrival averaged seven years—seven years of blades flashing at dawn and blurring into darkness; seven years of rotten cassava, rancid salted beef, parasites, whips; seven years before malaria, dysentery, or simple exhaustion carried off what remained.

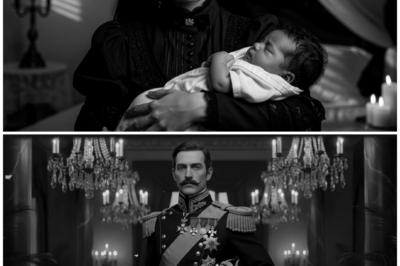

Among the seven most powerful planters stood Don Alfonso Méndez y Valverde, owner of San José, one of the valley’s most productive plantations.

At fifty-two, his face was leathered, his hands enormous, his eyes small and sunk beneath a permanent frown of authority.

He had a routine cruelty—administrative, efficient—he could call up without thinking.

Seventeen years earlier, Alfonso married fifteen-year-old Catalina Santa María, a girl from a once-noble family whose fortune had evaporated.

The wedding solved her father’s ruin; it upended Catalina’s life.

The cathedral filled; the reception lasted three days.

But everyone knew what the ceremony truly was: a sale.

Catalina moved into San José’s great house like a treasure placed on a mantle and left to gather dust.

By 1831, Catalina was thirty-two.

Her once bright honey-colored eyes had dulled to a candle’s last flame.

Heat stains marbled her skin.

Her hair, pulled into a severe bun each morning, had learned restraint from the rest of her life.

Three babies had died; her husband blamed her for all.

She lived between rooms that smelled of varnished wood, powder, and silence.

The San José estate sprawled over 800 hectares in the green bowl of the Yumurí valley—beauty bending into the sea, rivers like glass.

Everywhere the earth wept with lushness.

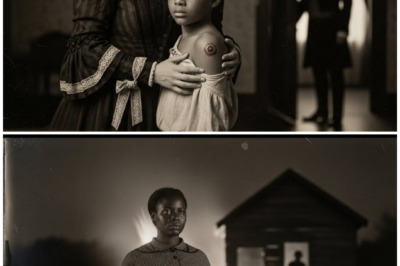

But the loveliness was interrupted by long, low slave barracks of rotting wood, where two hundred people were packed in conditions that would shame a prison.

The mill—trapiches, boiling cauldrons, smoke—ran day and night.

Into this world came Sebastián Valdés.

Purchased in January 1831 for an unusually high 800 pesos from an intermediary in Santiago de Cuba, Sebastián was twenty-eight and so striking that men stopped talking and women’s eyes refused to look away.

He stood around five feet eleven, coffee-with-milk skin, black wavy hair, a symmetrical face—high cheekbones, straight nose, full lips—framed by green eyes that glowed gold in certain light.

But it wasn’t beauty alone that made him dangerous.

It was presence.

He had the rare habit—unnatural for an enslaved person—of meeting eyes, and when he did, people felt seen through.

As if he weighed them—without words, without permission.

Among the enslaved, he earned a wary admiration.

He was kind in small ways—shared rations, quiet, calm—and never bragged.

But they sensed that a man like this drew lightning.

Beauty in a slave meant trouble, especially if the slave knew his beauty could be a weapon.

Sebastián was very intelligent.

As a boy in Santiago, he had learned to read in secret from an abolitionist priest who was later expelled for teaching slaves.

He read Plutarch in Spanish translation, memorized theater he would never see, studied the French Revolution and Haiti.

He drew a simple direct violence rarely worked for individual slaves; rebellion drew the lash and public torture meant to terrify the rest.

Manipulation, seduction, exploiting cracks in the armor—that was different.

That required patience and the willingness to become monstrous to destroy monsters greater still.

He arrived at San José with a plan—roughly sketched but ready to be sharpened.

Catalina saw him on the morning of January 15, three days after his arrival.

From the great house’s gallery—an airy, shaded corridor meant to shield delicate lives from the sun—she watched with her nacre fan held to her face.

Her mind, heavy with last night’s humiliation, drifted toward suicide—laudanum in the medicine cabinet within reach, a funeral she could picture like a painting.

She looked out and saw Sebastián shirtless, repairing a fence near the path.

Light pressed sweat into a sheen across his chest.

He straightened, wiped his forehead, and glanced toward the house.

Their eyes met for two seconds—brief enough to avoid insolence, long enough to send a shock through the dead part of Catalina’s heart.

He lowered his gaze and returned to work.

Something had happened.

She stopped moving the fan.

She realized she had been holding her breath.

She inhaled, and the world tilted.

The next three weeks, she became a ghost with purpose.

She found reasons to be on the gallery at certain hours.

Ordered fresh water for workers near the fence.

Invented inspections that kept her near him.

He seemed oblivious—worked silently, spoke when spoken to, eyes down—but Catalina noticed delicate adjustments: he always seemed to place himself within her line of sight; when she passed, his pace slowed—movements slightly pronounced, as if a stage note had been given and learned.

Their eyes met only twice a week at most.

Each time felt like electricity.

On February 8, everything changed.

Alfonso held a party to honor Don Rodrigo Salazar’s birthday—a dozen men of the sugar elite; music; brandy; a sea of smoke.

Catalina wore ivory silk, jasmine threaded into her hair.

She smiled until her face burned.

Around eleven, Alfonso made a joke about barren wives and glanced at her while his friends laughed.

Catalina nearly choked.

She whispered a polite excuse and slipped outside for air.

In the garden’s bougainvillea-warmed gazebo, she found Sebastián sitting on a granite bench, nearly invisible in shadow.

He rose at once, head inclined.

“Forgive me, señora.

I didn’t know you’d come here.

I’ll leave.”

“Wait,” she said—surprised at her own voice.

“What are you doing here?”

“The foreman asked me to watch the guests’ horses, señora.

I rested a moment.”

Catalina knew she should go.

Knew that standing alone with a slave man in the dark a hundred yards from fifty guests meant ruin.

She did not move.

“I’ve seen you working,” she said, unaccountably honest.

“You’re new?”

“Yes, señora.”

“From where?”

“Santiago.”

Silence knitted around them.

The music swelled; a door shut; the sound dulled.

“Look at me,” Catalina said.

He lifted his eyes slowly.

This time they did not drop.

Catalina felt the dam inside her body burst.

“You are very handsome,” she whispered—and hated herself and loved herself for the boldness.

“And you,” Sebastián said softly, clearly, “are the saddest woman I have ever seen.”

She should have called the foreman, had him whipped, demanded punishment.

Tears fell instead, cutting through careful powder.

“You know nothing about me.”

“I know your husband hits you,” he said.

“I saw the marks before the powder.

I know he speaks to you in public with the same tone he uses for his dogs.

I know you sit on the gallery each morning, not to watch work, but to search for any reason to feel something besides this slow death.”

Catalina sobbed.

Sebastián stepped closer—violating rules he had memorized since birth.

She did not retreat.

“You don’t deserve this,” he said, voice almost intimate.

“No one does.”

“There is no escape,” Catalina whispered.

“This is my life.

Until I die.”

“There is always escape,” Sebastián said.

“The question is what price you are willing to pay.”

“What are you talking about?”

Voices approached; Alfonso was calling for her—irritation laced with possession.

Sebastián receded into plants like a shadow folded away.

Catalina wiped tears, smoothed silk, and met her husband on the path.

He stared at her, drunk and suspicious.

“What are you doing here? We have guests.”

“Air,” she said.

“It’s hot inside.”

He sneered and led her back.

All night, Catalina replayed Sebastián’s words.

The price.

What price? She began to consider that there were things worse than death.

Two weeks later, she met Sebastián three more times—in the granary, the washhouse, and the gazebo by day while Alfonso traveled.

Each meeting bled deeper: he asked what she dreamed as a child, what books she loved, where she would live if she could.

She told him what no one had ever heard: a father who loved her and sold her; three babies born and buried; a night she tried to flee ten years earlier and was caught three kilometers from the estate, dragged back, locked in her room for a month.

Sebastián told pieces: a mother taken when he was eight; sold east; reading by stolen candle; men crushed into shells by slavery.

He had vowed he would be free or die trying.

February 24, the line crossed.

A small party swelled in the great house.

Catalina excused herself with a headache, waited, and slipped down the servants’ stairs to the far granary.

Sebastián had prepared a space: a blanket, an oil lamp.

They fell into each other like striking flint.

Catalina felt newness ignite in places she thought dead.

He was careful, attentive—asked what she liked, listened, adjusted.

She cried when it was over—relief, fear, guilt, hope—all braided.

“We’ve changed everything,” she said.

“We did what had to be done,” he answered.

“My husband will kill me if he knows.”

“Then he cannot know.”

“How long until someone sees us? Until a slave tells? Juana, or anyone?”

“There is another option,” Sebastián said.

“Kill him.”

Silence pulsed in Catalina’s ears.

She rose, tying silk with shaking hands.

“Are you mad? I’m not a murderer.”

“Why not?” he asked.

“He has been killing you slowly for seventeen years.

You would be returning the favor—quickly and more mercifully than he deserves.”

“I would be caught.”

“The laws protect men like him,” Sebastián replied.

“They also protect widows like you.”

“Doctors, authorities—”

“Arsenic,” he said.

“Mixed with his tobacco.

Six weeks of small doses.

It will look like tropical fever.

No one will suspect.”

“Where would I get arsenic?”

“I’ll get it.

Powder for rats in warehouses.”

“This is madness.”

“What’s madness is living as you do,” he answered, hands gentle on her shoulders.

“Waiting to be struck too hard; waiting until sadness consumes what’s left; waiting until he decides you’re more trouble than you’re worth and locks you in a madhouse.”

Catalina had thought of all those endings.

All were horrible.

“If I do it,” she said, “I’ll still be a widow.

Power will pass to his brothers or cousins.

You’ll still be a slave.”

“Which is why it cannot be just Alfonso.”

Catalina saw it—this wasn’t heat-born fantasy.

He had been planning before he met her.

“There are other women like you,” he said.

“Other wives in golden cages.

Other potential widows who could inherit property and wealth if their husbands die at the right time.”

“You mean—”

“Change the system from inside,” he said.

“Not with rebellion that is crushed in days.

With something more subtle, more permanent.

Widows have power here—more than you think.

They can sell land, free slaves, fund causes.

If there are enough of you, with shared interest in changing the order—”

“Do you know other women?”

“I’ve watched,” he said, naming six wives—Inés, Dolores, Rosa, Mariana, Lucía, Teresa—married to powerful men.

“I’ve begun with some as I did with you—attention, conversations, ideas.

I don’t force anyone to kill.

I show them that it is possible and help them do it.”

“And what do you gain?”

“Revenge,” he said.

“Against every man who treated me as less than human.

And, if we succeed, my freedom.”

Catalina asked for three days.

She came back in two.

“I’ll do it,” she said.

“Tell me how.”

He opened a dark glass vial, a small mortar, an assortment of Alfonso’s cigars.

Over an hour, he taught her how to open, dust, mix, reseal—how to dose over time.

He explained that he had already begun with others, moving between estates when lent by San José’s foreman; he had watched, measured, selected women whose desperation matched his risk.

That night, Catalina waited until Alfonso slept, stepped into his study, took five cigars from the cedar humidor, returned to her room, and worked by lamplight.

She resealed them with rice paper and saliva.

She did not feel guilt.

She felt purpose.

Week one: no change.

Week two: nausea, then violent vomiting.

Dr.

Aguirre bled him, prescribed broths; nothing helped.

Week three: diarrheal hours, hair falling, gray pallor.

Dr.

Aguirre brought a colleague from Havana, Dr.

Suárez—they saw “malignant fever.” Week five: hovering; thirty pounds lost; pulse irregular.

He died April 10, six weeks after Catalina began poisoning him—breathing stopped in the night.

Catalina screamed convincingly.

Grief, real and performed, spilled across the great house.

The funeral glowed with flowers and marble.

Sebastian stood among servants at the back, eyes briefly meeting Catalina’s—just enough to share the smallest smile.

One down.

Six to go.

But as Alfonso died, Sebastián already had one more: Don Pedro Cortázar fell into his own trapiche on April 14.

Official cause: accident.

In truth: Inés mixed rum into his midday drink, Sebastian had loosened floorboards where Pedro always stood, and placed a pile of cane in precisely the wrong place.

Pedro’s foot slipped; the machine caught him.

Inés fainted where people could see, cried where people would hear, and a week later stood at his funeral like a portrait.

Between April 14 and May 3, five more planters died:

— Don Rodrigo Salazar drowned in the Yumurí after Dolores laced his drink with laudanum before he swam.

— Don Martín Vega was killed by a “stray” hunting bullet chosen carefully by an enslaved man who accepted Rosa’s promise of freedom for his family.

He was executed afterward, but the money freed his wife and surviving child.

— Don Gaspar Ruiz convulsed and died—a “fever of the brain”—after Mariana spiked his wine with hemlock.

— Don Felipe Sotomayor suffered a sudden “heart attack”—Lucía used digitalis in fatal dose.

— Don Esteban Pacheco fell from his horse and cracked his skull after Sebastián treated Esteban’s saddle with an irritant derived from local caterpillars—precisely timed for a violent reaction at the rocky bend.

Seven men died in twenty-three days.

Matanzas whispered.

Havana responded.

Captain Rodrigo Torres arrived May 8—meticulous, incorruptible, relentless.

He interviewed everyone—widows, doctors, overseers, slaves.

He saw it: seven deaths in twenty-three days with differing causes; the statistical odds of coincidence were astronomical.

He called the seven widows, one by one, and saw something strange in their eyes: not sorrow, but relief.

Catalina met him May 10 in a private office.

He offered condolences, asked about “fever.” He probed gently.

“Your husband was robust.” He asked, “Do you know the other widows?” He asked, “Have you noticed anything unusual?” He said plainly, “I don’t believe in coincidence on this scale.

I believe someone is killing the planters.”

Catalina left terrified.

Torres was not a fool.

He would find Sebastián.

The entire plan would burn.

That night, Catalina met Sebastián in the granary.

All seven widows sent messages: Torres had interrogated them; his suspicion was rising.

Catalina wanted to run.

Sebastián was calm.

“We give him exactly what he wants,” he said.

“A culprit.”

Catalina stared.

“No.”

“Yes,” he said.

“Me.”

She could not breathe.

“They will torture and execute you.”

“I know.”

“Why?”

“Because it’s the only way to protect all of you,” he said.

“Torres will break someone.

He will keep pressing until one of you shatters, and if one falls, all fall.

If I confess and say I manipulated the wives with witchcraft, the authorities will accept it.

It is easier to believe a slave used brujería than to admit seven white women killed their husbands.”

Catalina cried.

He held her.

“You will lose me physically,” he whispered.

“But you will keep what we have done.

You will keep the truth: you are not powerless.

You can control your destiny.”

He asked one more thing: after his death, bring the seven together.

Form a pact.

Use wealth to free slaves, to fund abolition, to educate women.

Make his death mean something.

He told her about Carmen Hidalgo de Vargas—a young wife being destroyed by Don Luis Vargas.

Carmen had been too afraid to join; she might be ready later.

Catalina promised.

On May 12, Sebastián walked into the Capitanía General and confessed to Torres: “I killed the seven planters.

I seduced their wives.

I used my beauty and my words.

I mixed brujería into their minds.” Torres examined him—saw intelligence, saw that Sebastián was protecting others.

“You’ll be tortured,” Torres said.

“I know,” Sebastián answered.

“My story will not change.”

It did not.

Two weeks of torture left his body scarred, fingers missing, back a map of agony.

His confession did not waver.

The wives were victims under his spell.

He alone was guilty.

The trial was swift.

Colonial authorities wanted closure, not truth.

The crowd for the execution on May 3 was enormous.

The seven widows stood among the sea of faces, veils lowered.

Sebastián walked, chained, head high.

He found Catalina.

She lifted the veil enough to let him see tears.

He nodded once.

He found the other six.

Each made a sign.

When asked for last words, Sebastián spoke clearly:

“They call me seducer, witch, murderer, demon.

I accept those titles.

In a world built on slavery and oppression, sometimes a demon is required to balance the scales.

The men I killed were tyrants who built fortunes on African corpses, who treated their wives scarcely better than animals, who believed their money and skin entitled them to destroy lives without consequence.”

The judge ordered the hood.

As it fell, Sebastián raised his voice once more:

“To the seven women who know what truly happened—use your freedom wisely.

Use your wealth to change this world.

Never forget you had the courage to take your lives into your own hands.”

The trapdoor opened, the rope snapped, his neck broke.

He died quickly.

That night, seven women met in secret in the San José granary.

Catalina lit candles.

They sat on blankets in a circle—Catalina, Inés, Dolores, Rosa, Mariana, Lucía, Teresa.

They spoke until morning.

They formed a quiet brotherhood—no name, no banner—only purpose.

Each pledged to free five slaves that year—gradually, under pretexts that passed legal muster.

Each agreed to fund abolition discreetly, to educate girls of color, to teach enslaved domestics to read, to make reasons and systems for escape that did not require another murder.

They created codes to communicate, planned monthly meetings in different places, mixed blood in a clay bowl and buried it in the floor.

They swore to honor Sebastián’s sacrifice, to dismantle the system piece by piece, to support and protect one another, and to carry the truth forward.

In the years that followed, small changes took root.

Catalina—now simply the Widow Méndez—refused to marry again, hired a competent manager for San José, and spent her time and money on what she called charity.

She established a quiet school for free girls of color—teaching reading, writing, sums, and rights.

She purchased a property at the edge of town for safety—taught history that included the Haitian revolution and the idea that freedom was possible.

Inés sold the Cortázar estate, moved to Havana, and set up a boarding house that quietly sheltered fugitive slaves en route to ships bound for places where slavery was illegal.

Dolores spent three years and a small fortune tracking down the daughter her husband had sold and buying her back—she never left her again.

She used her money to buy enslaved children separated from families and reunite them.

Rosa remarried—a rare second chance of her own choosing—partnered with a Catalan merchant who shared her abolitionist leanings.

They created a legitimate import-export business that quietly moved information between abolitionists in Cuba, Spain, and the Americas.

Mariana, Lucía, and Teresa modeled similar courage: choosing their futures, selling land, freeing people, funding quiet operations that chipped at the edges of the order.

And Carmen—after Catalina’s note at Mass and a candle in her window—learned the truth.

Catalina gave her arsenic, taught careful dosing, coached her through performance when doctors came.

Six weeks later, Don Luis Vargas died of “typhoid.” Carmen became the eighth widow.

Captain Torres stayed two years, watching, taking notes, writing reports to Havana.

He suspected the truth, but his superiors wanted the case closed.

Years later, dying in 1855, he confessed to a priest that his greatest regret was lacking the courage to pursue the complete truth about the widows of Matanzas, even when it threatened the order he had sworn to protect.

Authorities suppressed Sebastián’s story.

Records mention a slave executed for multiple murders in 1831—no details, no wider web.

But among enslaved communities, the story lived—embellished, mythic, varied, alive.

In certain circles of educated women in Havana, truth circulated in whispers—proof that change was possible, that women were not powerless, that even in a system designed to crush them, cracks could be widened.

The brotherhood persisted.

By 1850, Matanzas had one of Cuba’s highest manumission rates—more schools for people of color than cities of similar size—and an unusual number of wealthy widows who never remarried, choosing control over their property and destiny.

When Spain finally abolished slavery in Cuba in 1886, institutions that made transition possible had been founded or funded by descendants of the original widows.

Catalina died in 1868 at sixty-nine.

In her will, she left her fortune to a foundation for girls—explicitly instructing that they would never be taught that their sole purpose was to serve men.

She left a sealed letter to be opened fifty years after her death.

In 1918, the letter was opened.

Names.

Dates.

Methods.

The entire story, written with the care of someone who wanted the truth to survive but knew it needed time.

Some called it a forgery.

Others saw it as confirmation.

It was studied, debated, archived, and mostly forgotten again—too disruptive, too morally messy.

The colonial past remains easier to teach as simple—cruel masters and submissive victims—than as a place where victims learn to become dangerous, where morality blurs and justice costs blood.

Today, traces remain if you know where to look.

A small plaque in the old Matanzas cemetery, placed quietly in 2005 by a feminist group, reads: “In memory of those who fought for freedom when freedom was unimaginable—may their courage not be forgotten.” A primary school at the edge of the city still bears the name Esperanza—its origin born in Catalina’s stubborn belief.

And in some Afro-Cuban families, stories linger—of a beautiful man who defied masters and showed trapped women they could be free.

The details shift with each telling.

The core remains: there was a time when the powerful learned their power was not absolute; when the oppressed remembered that submission was a choice, not a destiny.

The story of Sebastián Valdés and the widows of Matanzas demands uncomfortable questions that still matter.

When is killing justified? Is there a moral difference between slow, systematic violence and quick, decisive rebellion? Were the women murderers or revolutionaries? Was Sebastián a liberator sacrificing himself for the powerless or a manipulator using women’s pain to fuel his own vengeance? Perhaps the simplest answer is that they were both—victims and victimizers, liberators and killers, heroes and villains—depending on where you stand.

What cannot be denied: seven brutal men died; eight women found freedom; hundreds of enslaved people were eventually freed because of those women’s actions; an oppressive system was challenged in a way that reverberated for decades.

Was the price too high? Did the ends justify the means? Each reader must answer.

Before you judge too quickly, remember: it is easy to argue nonviolence when you are not being systematically destroyed.

Easy to ask for patience when you have waited seventeen years, or twenty-eight, or an entire life for change that never comes through peaceful means.

The widows did not ask to be cornered.

They did not choose to be born into a society that treated them like property.

They did not ask to marry men who beat and humiliated them.

But when the chance came—even stained with blood—they took it.

That, perhaps, is the most disturbing lesson: push people far enough, and they will find illegitimate options.

Sometimes those options work.

Sebastián’s life reminds us that beauty can be a weapon, intelligence more dangerous than force, and systems of oppression carry seeds of their own destruction.

They need only someone desperate and brave enough to plant them—and wait for harvest.

The widows remind us that women history often paints as passive victims were more complex, more potent: survivors who learned to use the tools of their oppressors, transformed victimhood into power, and refused to accept suffering as inevitable or deserved.

How far would you go for freedom? Were the widows justified? Was Sebastián hero or villain? The question will not leave you, and that is its point.

News

Master Bought an Obese Slave Girl to His Room, Unaware She Had Planned Her Revenge

Master Thomas Caldwell purchased Eliza on a sweltering June afternoon, his eyes sliding over her large frame as he counted…

The Runaway Slave Woman Who Outsmarted Every Hunter in Georgia, No One Returned

Here’s a complete story in US English, structured with clarity and pacing, and without icons. The Runaway Slave Woman Who…

The Countess Who Gave Birth to a Black Son: The Scandal That Destroyed Cuba’s Most Powerful Family

Here’s a clear, complete short story in US English, shaped from your draft. It keeps the historical spine, the courtroom…

The Slave Who Had 6 Children with the President of the United States — He Loved Her for 38 Years

Here’s a complete, self-contained short story shaped from your draft. I’ve kept the voice intimate and steady, built the plan’s…

The Mistress Hid Her Slave’s Child for 12 Years — Until Her Husband Found the Birthmark

The morning Constance Fairfax realized she loved the child more than her own soul, she understood she would have to…

The Plantation Lady Whose Desire Consumed Seven Slaves — The Ritual That Ended Her Dynasty

There are confessions that arrive too late to save anyone. The one discovered in the water‑damaged strongbox beneath Laurelwood’s collapsed…

End of content

No more pages to load