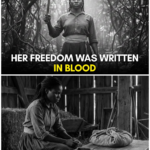

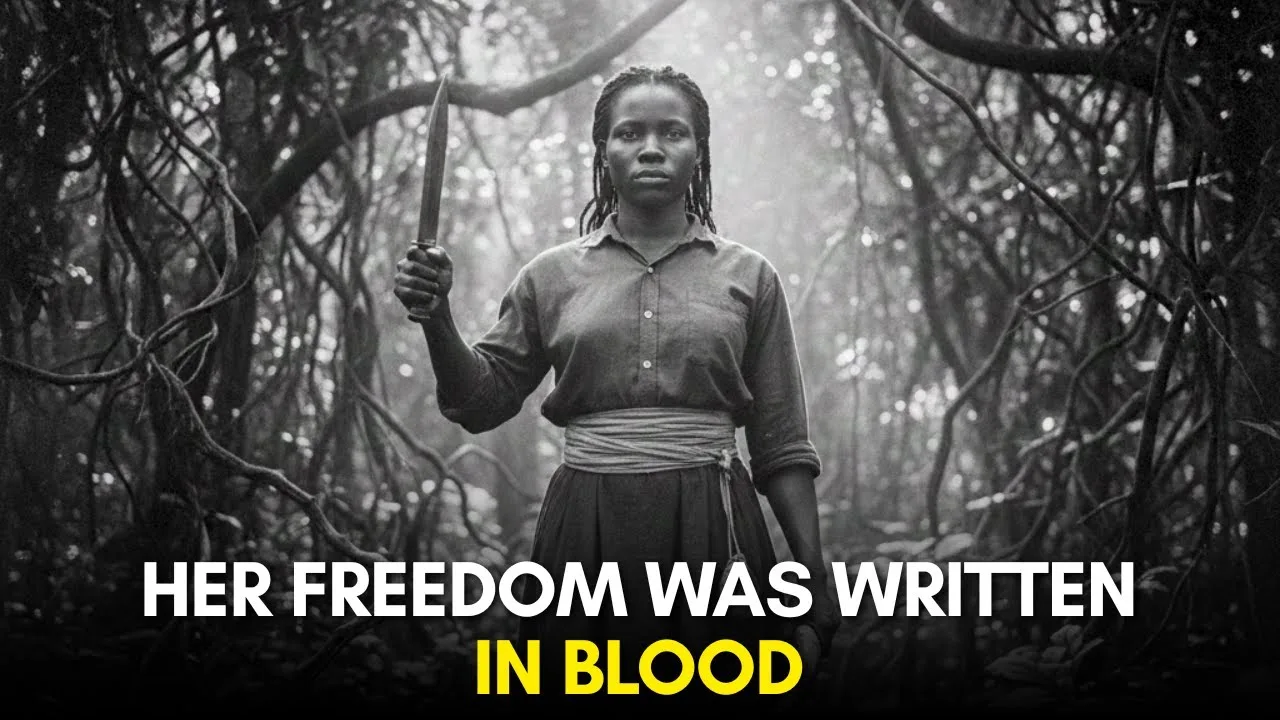

On nights when the swamp held its breath and the dogs stopped barking, a whisper moved through Tidewater Virginia like a current under black water.

It began as rumor in cabins, became prayer in churchyards, and turned to a name spoken carefully, as if saying it too loudly would wake the hounds: Ruth Ann.

She had been born on Mason’s Reach, a tobacco plantation tucked between cedar breaks and low marsh, where the soil ran red and the air felt older than memory.

By twelve, she had learned three kinds of silence—how to be quiet when overseers walked by, how to be quiet when women washed blood from shirts, and how to be quiet when the night carried sounds nobody could save.

By fourteen, she bore scar tissue in places you don’t speak of, because the master believed suffering kept people obedient.

By fifteen, she learned something else—the way cruelty changes its face but never its nature.

Master Silas Mason counted everything—bales of tobacco, lashes, sermons, and sins.

He saw himself as righteous, a man who loved order the way other men loved their own children.

The overseer, Pike, carried his whip like a sacrament.

The housemaid brought water and looked anywhere but at the girl whose small hands set cups that men would lift with fingers touched moments before by the master’s darkness.

The abuse began with “instruction”—a word Mason used to turn violence into morality.

He told Ruth Ann she needed to learn obedience.

He told himself God approved.

On nights when his wife left for her sister’s estate or slept heavily after laudanum, he sent the housemaid away and locked the doors.

Ruth Ann’s body became a place the law did not protect and the Bible did not comfort.

She learned every part of the house by scent—oak polished with tallow, pipe smoke sinking into curtains, the bitter edge of whisky that hid behind his breath.

You could measure her life by escape attempts that failed.

At sixteen, she made it to the river with a stolen knife and a half loaf of stale bread.

The dogs found her under a fallen sycamore.

Pike tied her to the whipping post and used a braided lash with wire threads woven through the leather.

Silas watched like a man attending service.

After, Ruth Ann did not speak for three days.

On the fourth, she rose when they told her to rise.

On the fifth, she began to gather things men don’t notice until it’s too late: times, habits, keys, roads, the way a lock responds when its tumbler is tired and worn.

There was a small boy in the quarters who asked her once if God hears us when we cry.

She said, “He hears.

Sometimes He waits.” She did not add the rest: sometimes God waits until you understand He gave you hands.

She learned men the way hunters learn deer trails.

Silas prayed at dawn and drank at dusk.

He visited the study after midnight, especially when rain kept him from the porch.

He kept a ledger of both tobacco and punishment, a catalog of numbers that made him feel powerful.

Pike walked the quarter row at five every morning and ten every night, always counterclockwise, always starting at the cabin by the ash tree.

The dogs fed at seven, growled at anyone who came near the kennels before he had finished, and slept lighter when the moon was full.

She learned women differently.

Mrs.

Mason was brittle and sick, bitter like the tea she drank and the pills that eased the bitterness briefly before sharpening it.

The housemaid, Leah, kept Maggie—her sister’s child—hidden in her eyes; it was the only way she could keep the girl safe.

The old woman who scrubbed floors in the big house hummed a tune that sounded like home.

She taught Ruth Ann to keep a bit of fatback in a cloth and a strip of linen inside the hem of her dress—things that change a night when you have to decide quickly.

If cruelty is a system, survival becomes a study.

That study turned into a plan so simple it should not have worked.

Simple plans do when executed perfectly.

Mason’s Reach held a harvest celebration every September.

Squires and planters came for roast hog and whiskey, for hymns sung loudly enough to drown the sound of coins changing hands.

Slaves worked in the kitchen, carried plates and poured punch, while overseers drank themselves into a dull fever that looks like laughter from a distance.

Security loosened where pride tightened.

Ruth Ann waited for that day like a patient blade.

Three weeks before the celebration, she began moving.

In the laundry, she found where the keys hung when Mrs.

Mason forgot to lock the pantry.

In the study, she learned that the window latch caught if you pressed upward and to the left while drawing the bolt.

In the kennels, she watched Pike measure laudanum for his own back pain, learned the shape of the bottle and the amount he said “won’t put a man down, just keeps him quiet.” She took notes that looked like house work: how long it takes to boil a ham, how long a candle burns, how long a man sleeps when he thinks his troubles are gone.

The celebration came on a Saturday that felt like heat pressed into fabric.

Ruth Ann carried platters, poured drink, and kept her eyes down.

Silas lifted his glass the way a judge lifts a gavel.

The hymns rolled smooth over the room.

At ten, the last guests left.

Pike stumbled toward his cabin, singing a hymn badly.

Mrs.

Mason had taken her pills and slept.

Silas unlocked his study to count money.

Ruth Ann stood in the doorway, hands folded, face empty.

“Girl,” he said, cheerful like a man who has eaten and thinks nothing on earth can touch him.

“Come.”

She came.

She watched him turn his back to the desk to fiddle with the coin box.

She pressed upward and left on the latch as she’d learned and slid the bolt between hinge and wood.

When the door jammed, he glanced but did not understand.

He was a man who believed that rooms imply safety.

The first motion surprised him—the speed of it, the precision.

She had boiled strips of linen hours earlier and wrapped them tight around the haft of a small hatchet until the handle fit her hand better than God ever made a handle fit a woman.

The hatchet entered near his collarbone, shallow, enough to break his breath.

He reached for the pistol in the drawer; she knew the drawer because she had dusted it and memorized the catch.

Her second blow struck his forearm—bone snapped with a sound like green wood breaking.

He shouted.

Leah, in the hallway, heard and did nothing.

That was her part in the plan.

Here is the truth: violence does not make anyone brave.

It makes some people free.

Ruth Ann moved through the room like someone who had memorized every angle.

She took the laudanum when the change of night came and poured the amount Pike used for himself into Silas’s whisky—enough to dull the edges and slow his feet.

She wrapped gauze around her hands and wrists—the old woman had taught her to do it before moving heavy things.

She took strips of rawhide from the pantry and used them to bind him the way Pike bound a hog for slaughter.

He cursed until his tongue felt heavy.

He laughed, briefly, believing men cannot be killed by girls.

He stopped laughing when he understood a fact he had never let himself consider: every person is a person.

Every person can die.

The first cut was shallow and messy.

You think you know where to place things until your hand becomes a measure, then your hand learns the math real quickly.

The second cut improved as practice improves.

She worked with patience that looks like mercy.

Sixty-six pieces sounds like rage.

It was discipline.

She removed rings and signet, took the keys she needed, and placed parts neatly into burlap sacks that had carried feed and now carried something else entirely.

At two, she opened the window and slid the sacks into a wheelbarrow she had boy’s hands for.

Maggie, Leah’s sister’s child with eyes like the kind you don’t let men see, rolled it to the smokehouse.

Smoke covers truth when used correctly.

She fed the fire with hickory, the kind that burned hot and steady, and began a different kind of work.

Leah stood watch.

The old woman hummed from the kitchen, slow, low, and without words.

You burn what you cannot bury when the earth is not yours.

At three-thirty, she took what she needed—money from the desk, a map of county roads, the pistol with three rounds, hard biscuits wrapped like a child wrapped in safety.

She picked up Mrs.

Mason’s keys, went to the room at the end of the hall, opened the door, and stood a moment in the quiet.

“Ma’am,” she said into the dark.

Mrs.

Mason stirred, eyes thick with medicine, mouth heavy.

“Your husband’s gone.”

Mrs.

Mason tried to speak.

Ruth Ann placed a glass near her mouth.

“Swallow,” she said gently.

The laudanum wasn’t for sleep.

It was for forgetting.

You can judge her if you need to.

The law would have.

She did not care.

She went to Pike’s door next.

The overseer slept with his boots on, mouth open, soul halfway to hell already just from living the way he lived.

She did not cut him into pieces.

That was for the man who counted.

For Pike, she used a rope and a chair.

Sometimes the simplest things are enough.

The rope held; the chair fell; the floor carries sounds you do not forget.

At dawn, Ruth Ann reached the river.

She had known a man years earlier who taught her something worth more than money.

He said, “White men hunt in straight lines.

Water makes lines curve.” She stepped into the curve, knees unbending until the cold turned her legs to wood and then to understanding.

She walked in that water the way a memory walks in a brain—careful, persistent, impossible to grab.

The dogs caught scent at the edge of the yard and lost it at the swamp.

Men search with pride; the swamp swallows pride before breakfast.

She reached a place where the water thins and the trees part into ground that wants feet less than eyes.

A Quaker family lived there—names not for paper; names for prayers.

They had built a low house with a sign you only see if you know what sign people like that use.

They fed her with bread and said nothing.

You help the way you can.

You don’t ask the kind of questions that teach you things you’d be forced to lie about later.

She stayed there two nights, then moved north.

The Underground Railroad is not a railroad.

It is people deciding together and separately to be better than the law.

Ruth Ann learned codes—a lantern left on a porch, a quilt pattern with a block turned sideways, a jar on a sill containing beans when it should have contained nails.

She slept in three places where fear could not climb the stairs because they had removed the stairs years ago for that reason alone.

She came to Philadelphia in winter, breath white, body a continent away from the place where it had been broken.

She found a church that smelled like wood and forgiveness.

She sat in the back and kept her hands folded because folded hands look honest in any country.

No one spoke of sixty-six pieces in the city.

That story stayed in the soil where it belonged.

On Mason’s Reach, panic moved like wind.

Men calculated timelines, then lied, then calculated again.

Pike’s death looked like accident, like a man drunk falling incorrectly.

There was no sign of Silas—no body, no boots, no sermons left undone.

Mrs.

Mason lived another three years, mostly in the company of her pills and her memory.

The plantation went to a cousin who hated it and sold it.

The quarter row burned one spring night—some say the old woman lit it; some say God did.

The slaves were sold to three estates, then two, then one, then freed at last, years later, by a war that turned the word “America” into something different.

Ruth Ann stayed quiet for decades.

She taught girls to sew and boys to read.

She used money from Silas’s desk to buy a small room above a shop.

She carried scars the way other women carried rosaries.

When asked about God, she said, “He hears.

Sometimes He waits.

Sometimes He hands you the knife.”

You want details.

You want to know where the sixty-six came from, what it looked like, whether she felt clean or dirty after.

That is a question you should ask yourself about yourself.

She felt nothing until she felt everything; then she placed the feelings into a jar with a lid and kept the jar in a place nobody else could find.

Survival is organization with blood on it.

A folk song moved through Virginia after the war—low, rhythmic, careful about names.

It spoke of a girl who “cut the devil into kindling” and built a fire that warmed people for a long time.

White men called it barbaric.

Black women called it accurate.

The law called it rumor.

The song did what songs do—it carried memory past fences.

An abolitionist’s journal, printed in 1869, told a story about a girl who “found justice where judges did not go.” He changed her name and the county, as you should when telling a truth meant to heal.

A county clerk wrote in the margin of a ledger, “Estate seized due to owner’s disappearance.” He also wrote, two lines down, “House burned.” The ink faded.

Fire stays.

One spring day in 1901, Ruth Ann sat in a chair near a window in a city far from the place of her birth.

A young woman asked her if she had ever regretted anything.

Ruth Ann looked at the girl like someone looks at a child asking whether the moon is a ball or a slice.

“I regret that he made me make the choice,” she said.

“I do not regret the choice.”

The girl asked, “Sixty-six?” Ruth Ann smiled the way old women smile when young women prove they can count.

“Some men are best remembered as ash,” she said.

“And some numbers are stories more than math.”

If you are looking for the moral, here it is: justice is not always legal; legality is not always justice.

In a world where a girl is property and suffering is policy, survival takes shapes that frighten people who have never had to prove their humanity.

Ruth Ann did not invent violence.

She converted it.

She did not build a system.

She broke one.

Years later, when the swamp breathes and the dogs stop barking, women in kitchens still hum a tune with no words.

Men drink quietly without understanding why their hands shake when they hear old songs.

A name moves through the air like a blade you cannot see.

It belongs to a girl who refused to be the kind of quiet men like.

You can judge her.

You can forgive her.

You can imagine yourself braver, kinder, wiser.

You can imagine yourself anything you want.

Ruth Ann learned the only truth that mattered to her: when the law is a whip, a knife can be a prayer.

And the number sixty-six is not just pieces.

It is the number of times a girl who had been treated like nothing told the world, one cut at a time, that she was not.

News

Three Widows Bought One 18-Year-Old Slave Together… What They Made Him Do Killed Two of Them

Charleston in the summer of 1857 wore its wealth like armor—plaster-white mansions, Spanish moss in slow-motion, and a market where…

The rich farmer mocked the enslaved woman, but he trembled when he saw her brother, who was 2.10m

On the night of October 23, 1856, Halifax County, Virginia, learned what happens when a system built on fear forgets…

The master’s wife is shocked by the size of the new giant slave – no one imagines he is a hunter.

Katherine Marlo stood on the veranda of Oakridge Plantation fanning herself against the crushing August heat when she saw the…

The Slave Who Tamed the Hounds — And Turned Them on His Masters

Winter pressed down on Bowford County in 1852 like a held breath. Frost clung to bare fields. Pines stood hushed,…

The bizarre secret of enslaved twin sisters in Mississippi history that no one has ever explained

In the summer of 1844, whispers began to glide through Vicksburg, Mississippi—first in quarters where enslaved people gathered after dark,…

This mysterious 1901 photo holds a secret that experts have tried to explain for decades

Dr.Elena Vasquez had restored thousands of photographs in twenty years—Civil War cartes-de-visite, glass plate negatives, cabinet cards yellowed by attic…

End of content

No more pages to load