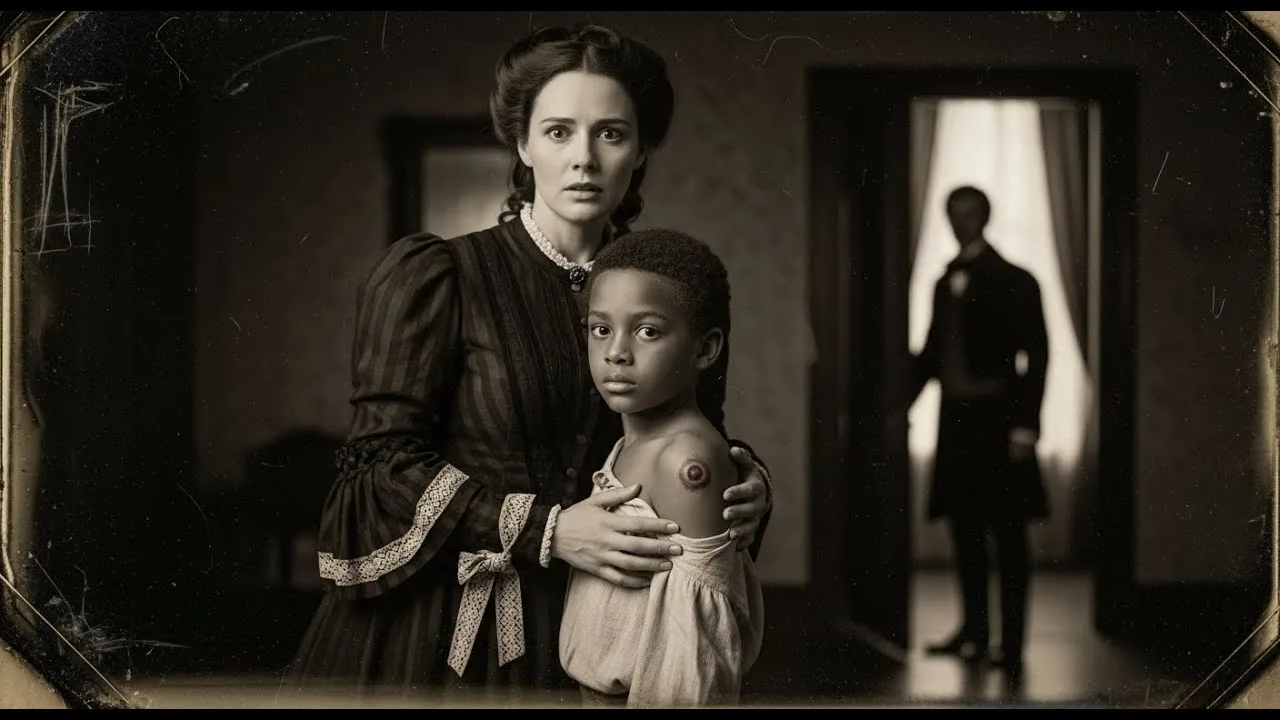

The morning Constance Fairfax realized she loved the child more than her own soul, she understood she would have to destroy them both.

It wasn’t the way little Samuel laughed—a bright, bell-like sound that rang through the kitchen house—or how his small fingers curled around hers when he thought no one was watching.

It was the birthmark: a wine-dark stain spreading across his left shoulder blade like spilled ink, identical to the one she had traced a thousand times on her husband’s back in the copper light of their marriage bed.

She had kept the boy hidden in plain sight for twelve years, dressed him in the rough-spun clothes of a kitchen servant, taught him to lower his eyes and flatten his voice.

But birthmarks don’t fade.

They only grow more damning with time.

Fairfax Hall sprawled across two thousand acres of Mississippi bottomland in 1857, when cotton was king and men owned other men’s children without ever seeing their own sin reflected back.

The house stood three stories tall, white columns rising like accusations toward a God who seemed to have abandoned that particular corner of the world.

Inside, Constance moved through rooms filled with French furniture and Belgian lace, her silk skirts whispering secrets against polished floors.

She had been seventeen when she married Nathaniel Fairfax, a man twenty years her senior, with tobacco-stained teeth and hands that left bruises shaped like accusations.

The marriage bed taught her about duty.

The mirror taught her about despair.

By their third anniversary, she understood that some cages are built from gold and locked from the outside.

Sarah arrived at Fairfax Hall when Constance was twenty-two, purchased at auction in Natchez, her humanity reduced by the bill of sale to measurements and monetary value.

She was nineteen, with skin the color of burnished mahogany and eyes that held depths Constance had never found in her own mirror.

Nathaniel bought her for the kitchen.

Constance saw immediately what her husband would eventually take.

It happened on a late September evening, the heat pressed down like a physical weight, even the cicadas too exhausted to sing.

Nathaniel returned to the house with hay clinging to his sleeves, untucked shirt, the smell of sweat and horses in his wake.

Sarah had been gone from the kitchen for two hours.

When she returned, something in her eyes had died—essential light snuffed out like a candle in a closed room.

Constance said nothing.

What words exist for the knowledge that your husband violated another woman while you lay upstairs listening to the bedframe creak through the floorboards? She took Sarah’s hand in the darkness by the ladder, squeezed once, felt a tremor run through the younger woman like electricity through copper wire.

“I’m sorry,” Constance whispered, though the words meant nothing, changed nothing.

“Sorry don’t raise the dead or make a person whole again, Mrs.,” Sarah replied, voice hollow.

By December, the pregnancy was impossible to ignore.

Sarah’s aprons hung wrong.

Her face took on a strange luminosity Constance recognized from her mother’s confinement portraits.

The other house servants whispered.

Nathaniel pretended not to notice—which meant he noticed everything.

One night in their bedroom, whale oil lamps threw dancing shadows across the damask wallpaper.

Nathaniel pulled off his shirt, and Constance saw it again: the birthmark she’d touched a thousand times without truly seeing.

It spread across his left shoulder blade like a map of some undiscovered continent—deep purple-red, irregular as a storm cloud.

“You’re staring,” he said, accusation edged in his voice.

“I was thinking about imperfections,” she replied carefully.

“How they mark us.

How they pass to our children.”

His eyes narrowed.

“What children? We have no children.”

The cruelty of it hung between them.

Five years of marriage, three miscarriages—emptiness echoing through the big house like a prophecy of extinction.

“No,” Constance agreed softly.

“We have no children.”

But Sarah did.

The baby came on a March midnight as spring storms rattled windows and lightning illuminated the quarters in white fire.

Constance attended the birth, sending away the plantation midwife with fabricated instructions about another emergency.

She’d read medical texts in secret, teaching herself anatomy the same way she taught herself French and Latin—desperate acquisitions of knowledge in a world that preferred women remain ornamental and ignorant.

Sarah’s screams cut through the storm—primal, terrifying.

Blood soaked through the linens Constance had brought from her own trousseau.

When the baby finally emerged—slick and furious and alive—Constance caught him in her own hands and felt something fundamental shift in her understanding of the universe.

“A boy,” she whispered.

Sarah, exhausted, trembling, reached for her child.

Constance laid him against his mother’s chest, watched him root, saw fierce love transform Sarah’s face from beautiful to something divine.

Then Constance saw the birthmark.

Small—the baby so new—but unmistakable: the same wine-dark stain across his tiny left shoulder blade; the same irregular edges; the same damning proof.

“You see it,” Sarah said.

It wasn’t a question.

“I see it.”

They sat listening to the storm while the baby suckled, oil lamp guttering, their shadows large against rough walls.

“He’ll kill him,” Sarah said finally.

“Master Fairfax’ll kill this baby sure as sunrise.

Can’t have no evidence of his sin walking around for the world to see.”

A decision crystallized in Constance—a mix of rage, guilt, and a love she hadn’t known she could feel.

“No,” she said.

“He won’t.”

The plan formed over days, refined over weeks, implemented over months—precision that would have impressed a general.

Constance announced her own pregnancy, padding her dresses with cotton batting, performing early motherhood like delicate theater.

She complained of nausea, craved strange foods, took to her room on careful schedules.

Meanwhile, Sarah nursed her son in secret, hidden in a small room behind the kitchen house that once stored root vegetables.

Constance brought food, clothing, blankets stolen from linen closets.

She watched Sarah sing to the baby in darkness, watched him grow strong, watched the birthmark spread like accusatory ink.

“What will you name him?” Constance asked one night.

“Names are for free children, Mrs.,” Sarah said bitterly.

“This boy got no name that matters.”

“He has a name that matters to you.”

A long silence.

“Samuel.

After my daddy.

Master sold him south before I learned to walk, but Mama told me his name every night like a prayer.”

“Samuel,” Constance repeated.

“It’s beautiful.”

When Constance’s supposed pregnancy reached term, she staged the most elaborate deception of her life.

She took to her bed, screaming through what she claimed was labor, while Sarah brought six-month-old Samuel—healthy, alert—through the servants’ entrance to the big house.

In the chaos of false childbirth—with doctors and midwives barred at Constance’s hysterical orders—she emerged with a baby she claimed as her own.

Nathaniel stood in the doorway, staring at the child with an expression she couldn’t read—suspicion, relief, desperate hope of a man facing extinction of his line.

“A son,” she said through manufactured exhaustion.

“You have a son, Nathaniel.”

He approached slowly, studying the baby’s face.

Samuel gazed back—Sarah’s intelligent eyes, not Nathaniel’s cold gray.

But babies look similar.

Men see what they want.

“He has your nose,” Nathaniel said finally.

Constance nearly laughed at the absurdity.

“And your stubbornness, I suspect.”

Nathaniel pulled aside the blanket to examine his supposed son.

Constance’s heart stopped—but Samuel was cunningly wrapped, left shoulder covered, right arm exposed.

Nathaniel touched the baby’s hand, watched tiny fingers curl around his own.

“My son,” he said, voice breaking.

“My heir.”

From that moment, Samuel inhabited two worlds.

To Nathaniel and plantation society, he was heir to Fairfax Hall—the boy who would inherit two thousand acres and two hundred enslaved souls.

But before dawn, Constance carried him down the back stairs to the kitchen house where Sarah waited to nurse him, hold him, pour love into the stolen hours they had.

“This ain’t sustainable,” Sarah said when Samuel was two.

“Boy getting bigger.

Soon he’ll talk.

Soon he’ll know.”

“He’ll never know,” Constance insisted.

“We’re careful.”

“Careful don’t change blood,” Sarah said.

“You can dress a thing up pretty, but truth show through the finest clothes.”

Years passed like water through cupped hands.

There, then gone.

Samuel grew tall and straight; educated by tutors from New Orleans.

He learned Greek and Latin, mathematics and rhetoric.

He rode horses; posture perfect; accent refined.

Everything screamed aristocracy—except when Constance caught him humming melodies Sarah had taught him, or saw his hands move—graceful, expressive—like his mother’s.

Sarah worked in the kitchen, growing older, quieter.

Constance watched her watch Samuel from a distance; saw hunger in her eyes when he passed through on his way to lessons.

Once, when Samuel was seven, he wandered in looking for cookies.

Sarah stood frozen, hands covered in flour, staring at her son like a drowning woman staring at shore.

“Hello,” Samuel said politely.

“What’s your name?”

“Sarah,” she managed, strangled.

“That’s a pretty name.

You make good cookies, Sarah.”

“Thank you, young master.”

After he left, Sarah collapsed against the worktable—body shaking with silent sobs.

Constance found her an hour later, still standing, still crying without sound.

“I can’t do this anymore,” Sarah whispered.

“Can’t watch my own child call me by my given name like I’m nothing but furniture.”

“I know,” Constance said.

“But what choice do we have? If Nathaniel discovers the truth, he’ll kill us all.”

“I know that, Mrs.

Don’t mean it don’t tear pieces out my heart every day.”

War came in 1861, and with it a terrible hope.

Nathaniel rode off in gray, convinced of righteousness.

He kissed Samuel goodbye, promised to return victorious—never knowing he abandoned his own blood son to chase the dream of keeping other men’s children in chains.

With Nathaniel gone, the deception was harder and somehow less urgent.

Constance let Sarah spend more time with Samuel—always carefully, under guises of household management or practical education.

Samuel learned herbs, coaxing flavor from simple ingredients.

Sarah taught without claiming the title of teacher; he learned without knowing he was learning love.

“Why does Sarah look at me that way?” Samuel asked Constance when he was ten.

They sat in the library; the boy sprawled on Turkish carpet, poetry open before him.

“What way?”

“Like she’s sad and happy at the same time.

Like I remind her of something.”

“Perhaps you remind her of someone she lost,” Constance said.

“The war has taken many people.”

Samuel considered.

“Do you think the war will end soon?”

“I don’t know.

I hope so.”

“If it does, and if we lose…” He paused, thoughts too large.

“What happens to Sarah and the others?”

“What do you think should happen?”

“I think people shouldn’t belong to other people,” he said carefully.

“It doesn’t seem right.”

“No,” Constance agreed softly.

“It doesn’t seem right at all.”

The war dragged.

News came in fragments—battles won and lost, casualties beyond comprehension.

Nathaniel’s letters brimmed with patriotic fervor and casual brutality—burned towns, destroyed crops, enslaved people fleeing to Union lines, the Confederacy bleeding out.

In one letter he wrote: Make sure Samuel understands what we’re fighting for.

Make sure he knows civilization depends on maintaining proper order.

A man must rule his household with a firm hand or chaos follows.

Constance burned the letter.

Watched the words curl to ash.

In March 1865 Samuel turned twelve.

The war was ending.

Everyone knew it, no one said it.

Confederate deserters slipped through at night, stealing chickens, spreading tales of Sherman and Grant.

Enslaved people whispered about freedom, Union soldiers, a world none could quite imagine but all desperately wanted.

For Samuel’s birthday, Constance organized a small celebration—just family, though “family” was strange in their house.

Sarah baked a cake with hoarded sugar and eggs bargained from a neighbor.

They gathered in the dining room—three of them—evening sun slanting through tall windows, dust motes dancing in gold.

“Make a wish,” Constance said as Samuel leaned toward candles.

He closed his eyes, face solemn with the weight of wishes.

When he opened them, he was looking at Sarah, tears tracking silently down her face.

“Why are you crying?” he asked.

“Sarah’s crying because she’s happy,” Constance said quickly.

“Because you’re growing into such a fine young man.”

Samuel’s expression suggested he didn’t quite believe it.

Later, Constance found Sarah in the kitchen house, sitting in darkness with her head in her hands.

“It’s getting harder,” Sarah said.

“Watching him grow up, watching him become a man, and he don’t even know.

He don’t even know his own mama standing right in front of him.”

“When the war ends,” Constance said, “when you’re free… maybe then we can—”

“Can what?” Sarah’s voice cut sharp.

“Tell him the truth? That his whole life’s a lie? That the woman he calls ‘Mother’ ain’t his mother and the woman who cooks his meals gave birth to him in blood and agony? That his daddy’s a rapist who owns his real mama like property? You think that knowledge going to set him free?”

Constance had no answer.

They’d built a house of cards in a hurricane.

Physics would have its due.

Nathaniel returned on a Thursday afternoon in late April—unexpected, unannounced.

He looked dug from a grave—gaunt, hollow-eyed—uniform hanging off a frame starved by war.

His eyes burned with feverish intensity.

“The war is over,” he announced, tracking mud across Persian carpets.

“Lee surrendered.

It’s all gone.

Everything we fought for, everything we built—gone.”

Samuel appeared at the top of the stairs, staring down at the stranger who claimed to be his father.

They hadn’t seen each other in four years.

The boy had grown; height and shoulders; childhood softness gone.

“Father,” Samuel said carefully.

“Come down here, boy.

Let me look at you.”

Samuel descended.

Nathaniel’s eyes tracked his son—assessing, measuring—finding acceptable or failing; Constance couldn’t tell.

“You’ve grown,” Nathaniel said.

“Nearly a man.”

“I’m twelve,” Samuel replied.

“Old enough,” Nathaniel muttered.

“Old enough for what’s coming.

They’re going to free them—all of them—turn them loose with no means to survive.

Chaos.

End of everything.”

Constance moved to stand beside Samuel, hand on his shoulder.

“Nathaniel, you need rest.”

“I need a drink,” he snapped.

“And I need to inspect my property.”

He stormed off toward his study.

Samuel looked up at Constance, questions in his eyes.

“Is he always like that?”

“The war changed him,” Constance said.

Perhaps the war revealed what had always been there.

Days passed.

Nathaniel grew erratic—patrolling boundaries, shouting at workers waiting for freedom; drinking from before noon to collapse; watching Samuel with intensity that made Constance uneasy.

“Something’s wrong with him,” Sarah said in the pantry.

“Guilt fever.

Get Samuel away.”

“I can’t just—”

“Mrs., listen.

Something bad’s coming.

I feel it in my bones.”

That night, Constance woke to sounds downstairs.

She pulled on a robe, descended back stairs, light spilling from Samuel’s room.

Voices through a cracked door.

“Should have told me earlier,” Nathaniel slurred.

“Boy’s twelve—needs to understand what’s expected.”

“Father, I don’t understand,” Samuel said.

“Take off your shirt, boy.

Need to see if you’re developing properly.”

Constance pushed open the door.

Nathaniel swayed beside the bed; Samuel sat up in his nightshirt, clearly uncomfortable.

“Nathaniel, what are you doing?”

“Checking my son,” he said.

“Making sure he’s strong.”

“It’s late.

Samuel needs rest.”

“I want to see his back,” he snapped.

“Check his spine.”

“Not tonight,” Constance said, putting herself between them.

“You’ve been drinking.”

Something flickered in Nathaniel’s eyes—suspicion or recognition—then he left, muttering about disrespect.

Constance sat on the edge of Samuel’s bed, hands shaking.

“Are you all right?”

“I’m fine,” he said.

“But Father’s changed, hasn’t he? Does war make people mean?”

“Sometimes,” she said.

“Sometimes it just shows us who they always were.”

“Mother,” he whispered.

“Do you love me more than anything—even more than Father?”

Constance thought about love and duty, lies and truth.

“Yes,” she said finally.

“Even more than Father.”

The next morning Nathaniel demanded they attend church—the first since war’s end.

The Methodist church had been a hospital; pews still bore blood that wouldn’t come out.

The minister preached normalcy—as if everything could return to what had been.

They rode in the carriage—Samuel sitting across from his supposed parents.

Sun slanted through trees, patterns of light and shadow across the boy’s face.

Constance watched Nathaniel watch Samuel—calculating—cold blood turning to ice.

After the interminable service, people gathered outside.

Constance saw other families—strain and loss carved into faces.

Whitfields lost two sons at Gettysburg.

Hendersons’ oldest came back missing an arm.

Connors’ daughter married a Union officer—scandal that wouldn’t be forgotten.

“How you’ve managed keeping that boy so healthy,” Mrs.

Henderson murmured.

“He looks strong as an ox.”

“Samuel’s always been robust,” Constance replied carefully.

“Takes after his father.”

“I suppose,” Mrs.

Henderson said.

“Though I don’t see much of Nathaniel in him—more of your coloring, your features.”

The observation hung like smoke.

Constance forced a smile.

“Children are mysteries.

Never know what they’ll inherit.”

On the ride home, Nathaniel’s jaw worked as if chewing thoughts too bitter to swallow.

Samuel read, oblivious.

Fields rolled by; slave quarters stood empty as inhabitants waited for freedom.

The world balanced on the edge of transformation.

That afternoon, Constance found Nathaniel drinking in the stables.

“We need to talk,” she said.

“About what?” he snapped.

“How everything I built is crumbling? How those savages will be turned loose?”

“About Samuel,” she said.

“You’ve been watching him.

What are you looking for?”

“I’m looking at my son,” Nathaniel said slowly.

“Trying to see myself in him.”

“And do you?”

A long pause.

“No,” he admitted.

“I look at that boy and don’t see myself anywhere.”

“Children don’t always resemble their parents,” Constance said.

“He doesn’t talk like me,” Nathaniel said.

“Doesn’t think like me.

Hell, he doesn’t even hold himself like me.

Sometimes I wonder…”

“Wonder what?” Constance’s heart hammered.

“Nothing,” he said, turning away.

Nothing was everything.

That night, Constance met Sarah in the kitchen house—long after Samuel had gone to bed.

They sat across from each other at the worktable—two women who’d shared an impossible secret for twelve years.

“He suspects,” Constance said.

“I know,” Sarah replied.

“If he finds out, he’ll kill us all.”

“There has to be a way,” Constance insisted.

“Some way to keep Samuel safe.”

“Only one I can see,” Sarah said.

“Tell the truth.

Tell it first—before Master Nathaniel shapes the story.

Tell it to Samuel.

Tell it to the law.

Tell it to God if you have to.”

“But Samuel—shock—knowledge—”

“Better a hard truth than a comfortable lie that gets him killed,” Sarah said.

“Boy’s strong.

He’ll survive the knowing.”

They talked through the night—plans made and discarded—new ones born.

By dawn: tell Samuel the truth on his thirteenth birthday—two months away.

Give him knowledge, give him choice, let him chart his course through wreckage.

Fate had other plans.

On a Saturday morning in early June, heat turned air to syrup.

Samuel swam in the creek after lessons.

He returned dripping, shirt clinging, laughing at a farm dog.

Nathaniel stood on the back veranda—another whiskey bottle in hand.

He watched Samuel pull off his wet shirt, wring it out—and saw it: the birthmark across Samuel’s left shoulder blade—identical to his own—impossible to deny.

The bottle slipped—shattered on boards.

Samuel looked up, startled.

“Father, are you all right?”

Nathaniel’s face went the color of old bone.

His mouth worked, no sound.

Finally: “Where did you get that?”

“That?” Samuel twisted, trying to see his back.

“I’ve always had it.

Mother said it was a birthmark.”

“A birthmark identical to mine,” Nathaniel murmured.

“How interesting.”

The world slowed.

Constance heard her heartbeat; cicadas; distant hymn from the quarters.

Everything sharpened because everything was about to shatter.

“Nathaniel,” she began.

“Don’t,” he said quietly.

“Don’t say a word.”

Samuel looked between them—beginning to understand something significant was happening.

“Mother—what’s wrong?”

Nathaniel descended the steps slowly—circling the boy—studying him.

Constance could see him assembling pieces—the eyes not his, the features that didn’t match, the birthmark damning them all.

“How old are you, boy?”

“Twelve.”

“Twelve years,” Nathaniel muttered.

“And you were born… nine months after I returned from Natchez… nine months after I bought that girl—Sarah.”

“I don’t understand,” Samuel said.

Perhaps somewhere deep down he did.

“Get Sarah,” Nathaniel said to Constance.

“Get her.

Now.”

Constance ran.

She found Sarah in the kitchen house already preparing to flee; somehow she’d known—felt the revelation like a distant earthquake.

“He knows,” Constance gasped.

“Heard the bottle break,” Sarah said.

“Heard him shouting.

I was about to run.”

“He wants you,” Constance said.

“Wants us together.”

Sarah straightened her apron, lifted her chin.

“Then I’ll go.

Been running my whole life.

Time to stand still and let the storm hit.”

They walked back—two women bound by love, guilt, a secret finally exploded.

Nathaniel stood in the yard with Samuel—who had put his shirt back on and looked small despite his height.

“Tell him,” Nathaniel commanded Sarah.

“Tell this boy the truth.”

Sarah looked at Samuel—twelve years of buried love and anguish surfacing.

“Master’s right,” she said quietly.

“Time for truth.

I’m your mother, Samuel.

Your real mother.

Ms.

Fairfax—she been protecting you, raising you, loving you as her own.

But you came from my body.

You my son.”

The words landed like blows.

Samuel staggered back, shaking his head.

“No.

That’s not—Mother—tell her she’s wrong.”

“She’s telling the truth,” Constance said, tears streaming.

“I’m sorry.

I am so sorry—but it’s true.”

Samuel’s face crumbled.

He looked from Constance to Sarah to Nathaniel, trying to understand a world reshaped in minutes.

“But you… you raised me.”

“I love you,” Constance said.

“That’s the one truth that never changed.

I love you more than my life.”

“And I’m your father,” Nathaniel said, voice like broken glass.

“That’s the other truth.

I’m your father.

She’s your mother.

And this woman—” he gestured at Constance “—conspired to hide you from me—made me raise a bastard as my son—child of a slave and her master—hidden in plain sight—a mockery of decency.”

“Don’t talk about him like that,” Sarah said, voice strong.

“He a child.

Your child—no matter how he came.”

“He’s an abomination,” Nathaniel roared.

“A living reminder of my sin parading as my heir.”

Samuel had gone pale.

“Father—Master Nathaniel—did you force her? Did you rape her?”

Nathaniel’s silence was answer enough.

“So I’m the child of rape,” Samuel said slowly—working through horror.

“Born to a woman enslaved by the man who violated her—raised by his wife who lied to me every day.

And now—what? What am I?”

“You my son,” Sarah said fiercely.

“Blood of my blood.

And you free—the war over—the proclamation coming.

You free.”

“But not legitimate,” Nathaniel said.

“Not my heir.

Not entitled to an acre or a dollar.”

“I don’t want your money,” Samuel said, voice breaking.

“I don’t want anything from you.”

He ran—toward the woods.

Constance started to follow, but Nathaniel grabbed her arm.

“Let him go,” he growled.

“Won’t change what he is.”

“And what is he?” Constance turned on him with fury she’d suppressed for years.

“What is he except the product of your sin? You raped that girl.

I protected your child.

I raised him kind and educated and good—everything you’re not.”

Nathaniel’s hand came up to strike.

Sarah caught his wrist.

“No,” she said.

“You done enough violence to women.

You ain’t doing no more.”

For a moment they stood frozen—a tableau of Southern Gothic horror—three lives twisted together by violence and lies and impossible love.

Nathaniel wrenched free and stalked toward the house.

“This isn’t over,” he called back.

“Law’s still on my side.

War might be lost—but I’m master here.

You’ll pay for what you’ve done.”

Constance and Sarah stood listening to cicadas, feeling the weight of twelve years’ secrets exposed.

“Go find him,” Sarah said.

“Find our boy.

Tell him—tell him everything.”

Constance found Samuel by the creek—sitting with his feet in the water—staring as if answers lived in the trout’s path.

“I know you’re there, Mother,” he said.

“Or should I call you Constance now? Mrs.

Fairfax? I don’t know what to call you.”

“Call me whatever feels right,” Constance said, sitting in mud-stained silk.

“I hope you’ll still call me ‘Mother.’ That’s what I’ve been in every way that matters.”

“Except blood.”

“Blood isn’t everything,” she said.

“I didn’t carry you in my body—but I’ve carried you in my heart since the moment you were born.”

“She watched me from a distance,” Samuel said.

“Sarah.

All those years I thought she liked me.

She was watching her son and couldn’t claim him.”

“Yes,” Constance said.

“It destroyed her—every day.

But she did it because she loved you.

Because we both knew Nathaniel would kill you if he knew.

Maybe not with his hands—but he’d sell you south or arrange ‘accidents.’ We hid you in plain sight.

We made you his heir.

It kept you alive.”

“Am I free?” he asked.

“What does that mean? I lived as a white boy—a planter’s son.

Now suddenly I’m… what? Black? Mixed? Something between?”

“You’re Samuel,” Constance said.

“You’re the boy who learned Greek and Latin—kind to animals—who thinks people shouldn’t own people.

You’re the boy who made Sarah smile when she thought no one was watching.

The boy I’ve loved since I held you—covered in blood—squalling in the storm.”

“You were there,” he said.

“When I was born.”

“I delivered you,” she said.

“Sarah and I—alone that night—lightning shaking windows.

You were furious—so full of life.

I knew I’d do anything to protect you—lie—betray vows—damn my soul.”

Samuel turned to her—Sarah’s eyes rimmed in red.

“Why would you do that—for someone else’s child?”

“Because the moment I saw you, you became mine,” she said.

“Not property—mine in the way love makes things ours.

Because I looked at Sarah holding you and knew no law or custom could make it right to let Nathaniel destroy that.

So I chose.

Maybe it was wrong—selfish—keeping you when I should have helped Sarah escape north.

I couldn’t let you go.”

“Does Sarah hate you?” he asked.

“I don’t know,” she said.

“Ask her.

I think we both loved you best we could—given impossible circumstances.”

“What happens now?” he asked.

“Nathaniel knows.

He’ll tell people.

Everyone will know I’m not his heir.

I’ll be…”

“You’ll be free,” Constance said.

“That’s not nothing.

When emancipation is officially enacted—you and Sarah will be free.

You can go north.

Get an education.

Make a life based on who you are—not who you pretend to be.”

“And you?”

“I’ll stay,” she said.

“Pay whatever price Nathaniel decides I owe.

You’ll be safe.

That’s all that matters.”

“I don’t want to leave you.”

“I know,” she said.

“But you have to.

This place—the South—is built on violence and lies.

It’s rotting.

You deserve better.”

They sat watching the creek flow—knowing this moment was temporary—that when they returned, everything would change.

Finally Samuel stood.

“I want to talk to her,” he said.

“To Sarah—my mother.”

Constance found them later—sitting close—Sarah tracing Samuel’s face like memorizing.

They were crying—and smiling.

Twelve years of stolen moments replaced by something real.

“I remember singing,” Samuel said.

“When I was small.

A voice—songs in a language I didn’t know.

Was that you?”

“Every night I could,” Sarah said.

“I come to your window and sing you to sleep, my baby.”

“I thought it was the wind,” Samuel said.

“Or angels.”

“Just your mama.”

Constance stood in the doorway—witnessing sacred reunion—dreaded because it ended her time as Samuel’s only mother—hoped for because Samuel finally knew origin—finally had both women who loved him.

“Mrs.

Fairfax,” Sarah said.

“Come in.”

They sat around the worktable—triangle of shared history and complicated love.

“I want to say something,” Sarah said.

“To both of you.

What you did, Mrs.—taking my baby—raising him as your own.

Part of me hated you for it.

Every day I watched him call you ‘Mother’—it felt like knives.

But other part knew you saved him.

Knew you loved him true.

I’m grateful.

God help me—but I’m grateful.”

“I’m sorry,” Constance said.

“For all of it.”

“We did what we had to survive,” Sarah said.

“Ain’t nobody judge us for that but the Lord.”

Samuel looked at the two women.

“What do we do now? Father—Nathaniel—he’ll do something terrible.

I saw it in his eyes.”

As if summoned, shouting rang from the big house.

Nathaniel’s drunk voice—calling for them—justice—reckoning—blood.

“He’s been drinking all day,” Constance said.

The kitchen house door burst open.

Nathaniel stood swaying—a pistol in his hand—eyes wild—face flushed with whiskey and fury.

“There you are,” he slurred.

“All three—the liar, the whore, the bastard.

My perfect little family.”

“Nathaniel, put the gun down,” Constance said, standing, placing herself between him and them.

“Put it down.”

“Why would I?” he snarled.

“For the first time in twelve years I see clear.

You cuckolded me—made me raise another man’s child as my own.”

“He’s your child,” Constance said.

“Your blood.

The birthmark—the features—if you look—”

“Don’t twist,” Nathaniel hissed.

“I’m the victim.

I was deceived.”

“You’re the rapist,” Samuel said, standing.

His voice was steady despite the muzzle pointing at him.

“You raped my mother.

All the lies, the deception—it started with your violence.”

Nathaniel’s hand shook—the pistol wavering.

“Watch your mouth, boy.

You’re nothing.

Nobody.

No right to speak—”

“I have every right,” Samuel said.

“I’m your son—your firstborn—and you are exactly what I said.”

The gunshot was everywhere at once—deafening in the small space.

Constance screamed.

Sarah lunged.

Samuel looked down—blood spreading across his shirt.

“No,” Constance heard herself saying.

“No—no—no.”

Samuel touched blood—surprise flickering—then legs gave out.

He fell.

Sarah caught him—lowered him.

Constance pressed hands to his chest—trying to stop what wouldn’t stop.

Sarah cradled his head—sang one of those old songs at his window.

“Mama,” Samuel whispered—looking at Sarah.

“I’m sorry I didn’t know sooner.”

“Hush now, baby.

You gonna be fine.”

“And, Mama,” he said—turning to Constance.

“Thank you—for everything.”

“Don’t,” Constance sobbed.

“You’ll live—”

They knew he wouldn’t.

The wound was severe; blood loss great.

The light dimmed in his eyes.

“I wish…” Samuel coughed—blood at the corner of his mouth.

“I wish we’d had more time.

The three of us.

Real.”

“We have time,” Sarah said—tears streaming.

“We have right now.”

“Tell me about my grandfather,” Samuel said.

“About Samuel.”

Sarah told him—voice breaking—about strength and dignity and a love that survived separation.

Constance held his hand—told him about the night he was born—storm and lightning—how perfect he was—even covered in blood.

They talked until he couldn’t answer—until breath came shallow—until the light left his eyes.

Sarah’s sound wasn’t human—pure anguish.

Constance collapsed forward—forehead on Samuel’s still chest—certain her heart would stop too.

How could it keep beating when he was gone?

They stayed like that a long time.

The doctor never came.

Later they learned Nathaniel rode into the night with the pistol and shot himself in the woods—beneath a magnolia—brains scattered across roots.

The war had ended.

The Confederacy had fallen.

Fairfax Hall stood empty except for two women and two bodies, one young, one old—both destroyed by the same system of violence and ownership finally crumbling into dust.

They buried Samuel and Nathaniel in the family plot—side by side—father and son in death, if not life.

The minister spoke of tragedy and God’s mysterious ways.

Constance barely heard.

She stood beside Sarah—their hands clasped—and thought about birthmarks—how they mark us—how they pass—how they damn.

Emancipation came the following week.

Sarah was officially free—freedom feeling hollow with Samuel gone.

She stayed that summer—helping Constance settle the estate—helping her find strength to survive each day.

“What will you do?” Constance asked one August evening as they watched sunset over fields.

“Go north,” Sarah said.

“Make a life where nobody know my history.

Where I’m just Sarah—not Sarah the slave—not Sarah whose son was murdered by his own father.”

“And me?” Constance asked.

“Will you forgive me?”

Sarah was quiet.

“I don’t know if ‘forgiveness’ right.

What you did—taking my baby—raising him as your own—hurt me every day.

But it also saved him—gave him twelve years he wouldn’t have had.

Twelve years of love and learning.

So maybe it ain’t ‘forgive.’ Maybe it’s understanding we both did the best we could with terrible choices.”

“He loved us both,” Constance said.

“In the end he did,” Sarah replied.

“And we loved him.

In all this darkness—that’s something.”

They sat as light faded—two women bound by love and loss—and a system that destroyed them all.

When Sarah left the following week—heading toward Chicago with money Constance raised by selling the plantation—they embraced like sisters.

“Take care of yourself, Mrs.

Fairfax.”

“You too, Sarah.”

Constance watched her walk down the long drive—a free woman finally—though freedom cost everything.

She lived another forty years—growing old in the big empty house—surrounded by ghosts.

Sometimes late at night she swore she heard singing—voice at the window—old songs in a language she didn’t understand.

She’d look out—see moonlight and magnolia and eternal southern darkness.

She knew who it was—Sarah or memory of Sarah or love that couldn’t die when everything else did.

She’d whisper into the dark, “Sleep well, Samuel.

Your mothers are watching over you still.”

The story of Fairfax Hall became legend in that part of Mississippi—the plantation where a mistress hid her husband’s child for twelve years; where a birthmark revealed truth too late; where violence finally consumed everyone it touched.

People told different versions—some more sympathetic to Constance, some to Sarah, some to no one.

The real truth was simpler—and more terrible: three people who loved a boy in a world that didn’t allow that kind of love; who tried to protect him from a system built on owning human souls; who failed—as perhaps they were destined—because you can’t build anything lasting on violence and lies.

The birthmark—a wine-dark stain—became a symbol: a reminder that the sins of the father visit the children; that secrets surface; that blood tells truths we’d rather keep hidden.

And sometimes, on quiet nights near the ruins of Fairfax Hall, people swear they hear singing—lullabies carried across years—to a child who died too young, loved too much, caught in the crossfire of a history that ground up everyone in its path.

These are the stories from the shadows of history—impossible choices and love that defies boundaries.

They are truths we need to remember, even when they hurt.

The past isn’t past.

And the birthmarks we carry—literal and metaphorical—tell stories we cannot escape.

News

Rich twin brothers tormented an enslaved mother — 3 hours later, they met her deaf 2.2m-tall son

The twins were the kind of men a broken world creates when cruelty finds money and grows up without consequence….

7 hunters entered an abandoned house hunting an enslaved boy… only one made it out alive (1861)

Seven men stepped off the road and into the timberline on September 23, 1861. Lanterns swung in humid arcs. Rifles…

The mysterious secret of the Black boy who spoke to animals – an unexplained case from in 1857

The Unexplained Case of Joseph Brown: The Enslaved Boy Who “Spoke” to Animals in 1857 In the winter of 1857,…

She Killed Her Husband for a Slave—And the Slave Chose Her Daughter Instead

The morning Delilah Ashmore killed her husband, she wore her wedding pearls and hummed the hymn her mother reserved for…

She Was ‘Unmarriageable’—Her Father Gave Her to the Intelligent and Talented Slave, Virginia 1856

I was seventeen courtships into humiliation by the time my father made his most audacious decision. In Charleston parlors, they…

(1865, Sarah Brown) The Black girl with a photographic memory — she had a difficult life

In the spring of 1865, as the war sputtered toward surrender and lawmakers hammered freedom into the Constitution, a seven-year-old…

End of content

No more pages to load