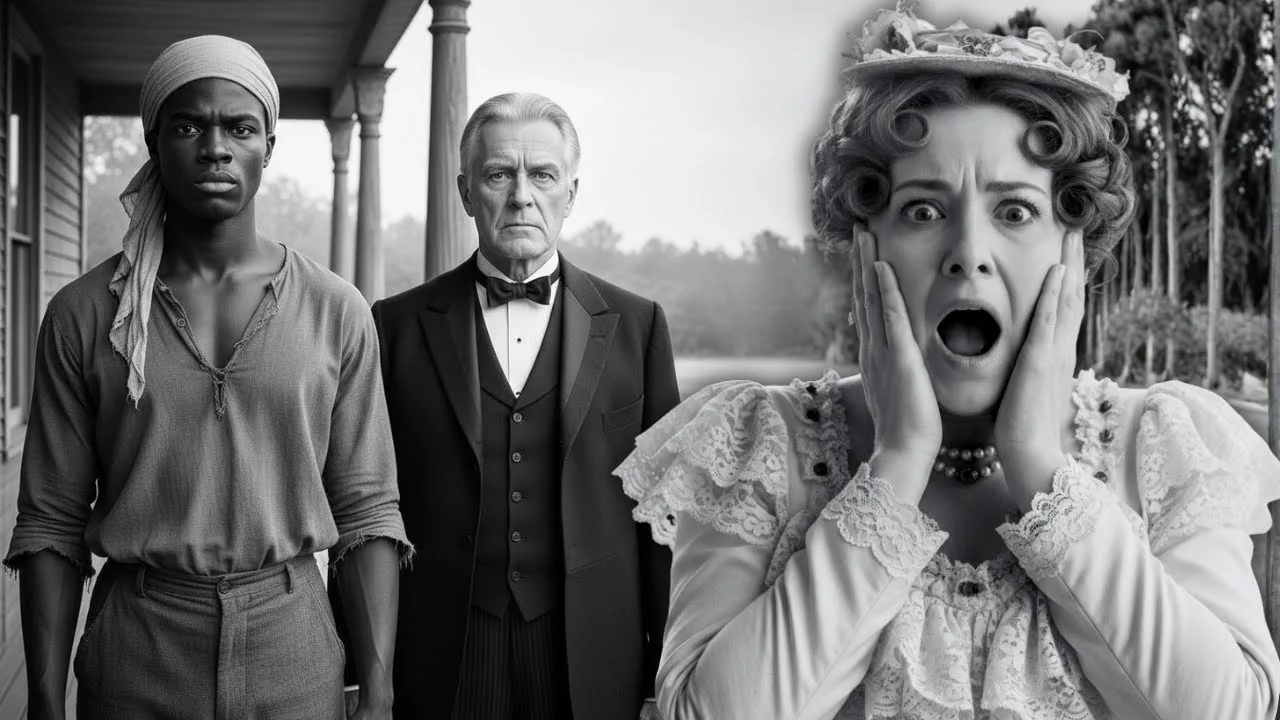

Katherine Marlo stood on the veranda of Oakridge Plantation fanning herself against the crushing August heat when she saw the dust cloud roll up the long drive.

The wagon clattered over ruts, its wheels dragging a curtain of pale grit across the yard.

Her husband, Richard Marlo, rode beside the driver, face flushed and smiling the way he always did when he believed he’d made a profitable purchase.

It wasn’t the wagon or the ledgers peeking out of Richard’s satchel that made Katherine’s breath catch.

It was the man chained in the back.

He was huge.

Even bent forward with wrists locked to the wagon bed, he seemed taller than the guards seated beside him.

His shoulders blocked sun.

His hands, bound at the knuckles, looked as if they could crush stone.

Yet something about him struck her as off.

He kept his head lowered.

A cough racked him now and then—wet, heavy, the sound of illness.

His shirt hung loose, as if he’d lost weight.

He swayed when the wagon stopped.

“Catherine,” Richard called, voice bright, already rehearsing his victory.

“Come see what I’ve brought home.

Wait until you see the size of this one.

He’ll do the work of three men.”

Katherine moved down the steps, silk skirts whispering, fingers tight on the rail.

She had watched many enslaved people brought to Oakridge.

Forty-three lived there now.

None had looked like this.

As she drew near, the man lifted his head just enough for her to see his eyes.

Dark.

Sharp.

For an instant, thought flickered across them—calculation, strategy—before his gaze dropped.

The cough returned, a body’s way of closing the curtain.

“He’s sick,” Katherine said, stepping back despite herself.

“Richard, tell me you didn’t pay full price for someone who’s ill.”

Richard laughed, boisterous, careless.

“Minor, minor.

Seller swore it’s weariness from travel.

A few decent meals and he’ll be strong again—stronger than any we’ve got.

Look at him.

Those arms.

Those shoulders.

Got him for half because of that cough.

Best bargain of the year.”

Katherine wasn’t convinced.

There was a tension in the way the man carried himself—weakness performed, strength hidden.

Depth in his eyes she didn’t care to see.

“What’s his name?”

“Calls himself Jonas,” Richard said, waving the guards to unlock the chains.

“Says he was a field hand in South Carolina.

Owner died; property sold.

Strong worker.

No record of running.

Perfect fit.”

When the iron fell away, Jonas stood slowly.

Katherine had to tilt her head to meet his face.

He was close to seven feet tall.

He swayed, caught himself on the wagon slat.

“Careful, big man,” a guard said with a chuckle.

“Don’t go breaking something before you’ve done a day’s work.”

Jonas nodded, obedient, and let them lead him toward the quarters.

Katherine watched him go, unease knotting in her chest.

“You worry too much,” Richard said, sliding an arm around her shoulders.

“He’s nothing but a big, simple laborer.

Nothing to think about.

Come inside.

I’m starving.

Bessie’s made something fine.”

Katherine let him steer her back into the shade.

At the doorway she glanced once more toward the quarters where Jonas disappeared.

She couldn’t shake the feeling that her husband had brought home a change—a kind of storm—and she did not know whether it would heal or break.

What Katherine didn’t know—what no one at Oakridge knew—was that Jonas was not his name.

He had never been a field hand.

He had never been mild or weak.

The cough, the bent posture, the sickly appearance—every bit of it was deliberate.

His true name was Elijah.

He was thirty-two years old, born free in the Tennessee mountains to Ruth, who had escaped Oakridge decades earlier, and to Samuel, a legendary tracker who had slipped slavery’s net and taught his son the forest’s arithmetic.

How to read trail and wind.

How to move without announcing himself.

How to think like a hunter.

“A hunter doesn’t chase,” Samuel had taught him.

“A hunter studies.

Learns habits, sees weak points, measures fear.

Then sets a trap the prey steps into without knowing.”

Elijah had become the best hunter in his valley, supplying meat for his community, guiding men who could afford to pay without asking questions about papers.

He had a small cabin, a wife, a life carved from hard dirt and cold nights and the dignity of being free in a country that often refused to see him.

Three years before the wagon rolled into Oakridge, everything changed.

Slave catchers found his mother.

They came at night with dogs, chains, and federal law.

They nailed a notice to the door: “Property of Richard Marlo, Oakridge Plantation, legally reclaimed.” The Fugitive Slave Act recognized no time passed, no family built.

Ruth was bound back to the world she had outrun when Elijah was a baby.

Elijah returned from a hunt to find his father battered and their cabin in splinters.

He held Samuel and listened to the apology of a man who’d fought as much as a man could fight.

Inside Elijah, anger sharpened to a blade.

He would bring her home.

He would not rush.

Hunters do not rush.

He began to study Oakridge.

He learned the land’s shape—400 acres of cotton and tobacco cupped by fences and patrol routes that cut like stitched lines.

He learned the names of overseers—six in total—who carried guns and drank hard.

He learned about dogs, about punishment, about who visited, who bragged, who listened to the sheriff’s voice.

He learned about the man at the center, Richard Marlo—wealthy, brutal, careful about money, careless about everything else.

A direct rescue meant death.

Infiltration meant possibility.

He traveled south and let a patrol catch him.

He bent his back and lowered his eyes and offered false details—runaway from South Carolina, confused, frightened, simple.

He inhaled dust to irritate his throat until the cough sounded convincing.

In Augusta’s slave jail, he kept up the act for two weeks, entering the “uncertain health” category where size meant value and illness meant discount.

Richard Marlo attended those auctions, looking for bargains that die slow and yield fast.

When Elijah—Jonas to the auctioneer—stepped onto the block, hunched and coughing, Marlo’s eyes lit.

He bid with confidence.

He won.

Elijah had entered Oakridge as property.

The first days were calculated misery.

He lifted and bent and obeyed.

He coughed when men watched.

He kept his face blank.

At night, when moonlight thinned shadows, he moved through the plantation like a thought: counting patrol steps, mapping blind corners, finding which doors squeaked and which did not, noticing which locks had been oiled, which chains had rusted.

He listened in the quarters.

People spoke in whispers so thin they barely counted as sound.

Fear had been layered so carefully here that imagination starved.

When he asked Moses, the scarred man in his cabin, “Anyone ever make it out?” silence followed like a tide.

Moses looked at him with pity and warned him not to think that way.

“Run and you die.

Or worse.

Marlo doesn’t just whip.

He ruins.”

Elijah lied and nodded.

He learned who still carried sparks—Abigail, older and strong in ways that don’t show in muscle; Samuel, young and angry; Clarara, in the house, listening invisible; Hannah, in the kitchen, quiet and everywhere.

He did not tell them his name.

He became a man who listened and remembered and did small kindnesses.

On a Sunday, under the cover of routine, he found Ruth in the garden behind the women’s quarters, fingers in earth, hands coaxing tomatoes from dry ground.

“Mama,” he said without lifting his eyes.

Her hands stilled.

Breath halted.

She turned and saw what she feared and hoped in the same heartbeat.

“No,” she whispered.

“You can’t be here.

What have you done?”

“I came for you,” Elijah said.

“I’m taking you home.”

“You fool,” she said, tears bright, not unkind.

“Do you know what they’ll do if they learn this? To both of us?”

“They won’t know,” he said.

“Not until it’s too late.”

“How?” her voice shook with truth.

“Six overseers.

Five dogs at night.

Marlo’s friends are sheriffs.

Even if we ran, they’d catch us before ten miles.”

“Then we don’t run,” Elijah said.

“Not yet.

Trust me.

I’m a hunter.”

Ruth looked at her son and, for the first time in years, felt that old word—hope—rise like heat.

He asked for information and patience.

She gave both.

She whispered about schedules and habits, about the study with the gun and ledger, about the harvest celebration when masters got drunk and guards got sloppy and slaves were all inside, all eyes on silver and plates.

“When?” he asked.

“Six weeks,” she said.

“Early October.”

“Perfect,” he said.

Six weeks is a long time when your cover is sickness.

Elijah measured days with coughs, backed by real effort, until the cough could fade without suspicion.

His picking rose—half basket, three-quarters, full.

Overseers nodded.

Richard, on a rare field visit, commented that the giant was finally earning his keep.

Katherine watched more closely than anyone.

She rode through the fields and fixed her gaze on him longer than was polite or safe, as if trying to guess a word someone else had tried to erase.

One noon she stopped her horse by the water bucket.

“You,” she said sharply.

“Jonas, isn’t it?”

“Yes, ma’am,” Elijah said, eyes on dirt.

“You’ve been here a month.

You’re stronger.”

“Yes, ma’am.

Thank you, ma’am.”

“Look at me when I speak.”

He raised his eyes slowly, obedient and empty.

“There’s something about you,” she said, head tilted.

“You’re not like the others.

Maybe smarter.”

“I just work hard, ma’am,” he said, middle answer, not dull, not bright.

“Don’t want to be sold south.”

“Good,” she said.

“Fear keeps you obedient.

Fear keeps you alive.” She turned her horse, then paused.

“My husband thinks he got a bargain.

I wonder if you’re more trouble than you’re worth.”

She rode away, and Elijah felt his heart pound with the particular danger of being seen.

That night, in the garden’s hush, Ruth told him Catherine’s eyes had always been the sharpest thing at Oakridge.

“She can’t act on suspicion alone,” Ruth said.

“Richard counts money louder than she counts doubt.”

At five weeks, Elijah began to recruit.

There is a way to ask people for their courage without breaking them.

He asked Abigail first.

“If a real chance came,” he said softly, “not a dream, would you take it?”

Abigail studied him.

“Who are you?” she whispered.

“You’re not what you pretend.”

“I keep promises,” Elijah said.

“I promised to free my mother.

I need people I can trust.”

She looked past fear and nodded.

“Tell me what you need.”

Samuel, Clarara, Moses, Hannah—one by one, he gathered five who still had bones strong enough for risk.

He told them only what they needed to know.

He explained the timing, the patrols, the dogs, the ledger.

He warned them.

Every one of them understood that a small chance was better than a lifetime of none.

Three days before the celebration, Richard gathered slaves in the yard and made a pronouncement in the voice of a man who liked hearing himself.

“Best cotton yield in five years,” he said.

“Party Saturday.

House slaves inside.

The rest stay in cabins.

Overseers will check.”

Elijah felt plans tilt.

Regular checks meant movement.

Movement could be timed.

That night behind the storage barn, he laid out adjustments.

“If they’re walking, they have a route,” he said.

“Routes can be mapped.”

Hannah volunteered to watch overseers by the kitchen door and mark their rhythm.

Clarara would carry timing from room to room.

Moses would receive it, calculate the window, and move the quarters when the patrols were far.

“So we won’t run blindly,” Samuel said.

“We’ll run in the quiet.”

“First,” Elijah said, “we put the dogs to sleep.”

Hannah named the bottle in Catherine’s cabinet—laudanum.

“Enough to make them sleep,” Elijah said.

“Not enough to hurt them.” He would not add harm to an animal trained to do what it had been taught.

He would add sleep.

“Then the horses,” he continued.

“We don’t steal them.

We release them.”

“Chaos,” Moses said, understanding.

“Chaos buys time,” Elijah said.

“They can’t chase on foot.”

“And the ledger,” Clarara said, eyes on the piece that mattered most.

“The ledger,” Elijah said.

“We ruin it.”

The day arrived.

Oakridge buzzed—silver polished, glass set, meat roasted, voices raised.

In the late afternoon, field hands were sent to the cabins.

As evening fell, carriages arrived, guests in fine fabric, overseers posted at doors and corners, whiskey poured in measures that make men forget their jobs.

Elijah went to the kitchen.

Hannah met him with a small nod—the signal that the dogs had eaten and would not wake for hours.

Bessie, the kitchen’s spine, demanded extra hands.

Catherine rushed in, looking for chairs no boy could lift.

Elijah offered to help.

Suspicion crossed Catherine’s face like a cloud; practicality burned it off.

“You work under Clarara,” she said.

“You do exactly as told.”

For two hours, Elijah moved furniture and carried trays, eyes down, mind up.

He studied exits, shadows, the way light pooled near the study hall.

He watched Richard drink himself proud.

“Look at that big fellow,” Richard said, pointing at Elijah for his guests—half price, three men’s labor.

Laughter folded over the room.

Elijah’s face stayed blank.

Inside, his ledger clicked.

By nine, Richard was sloppy drunk.

Overseers inside—Pike, Turner, Crawford—slurred their watch.

Outside, Hannah’s timing threaded back to Clarara, then to Moses.

Patrols had become predictable—every thirty minutes, talking more than checking.

Elijah caught Clarara’s eye and nodded toward the study hallway.

Clarara made a noise that won the room—dropped glasses, shattered sound.

Heads turned.

Elijah slipped down the hall.

The study door lock was old.

A thin strip of metal in his boot found tumblers and made the quiet click that opens danger.

Inside, a cabinet waited—the ledger, the gun, the small bag of coins.

The lock on the cabinet was not old.

He needed the key around Richard’s neck.

He stood still and measured risk.

Leave the ledger and run with weak information? Or take the bold path hunters sometimes take when nothing else will do?

He chose bold.

He returned to the hall with a wine bottle.

“More, master?” he asked gently.

He stumbled as he poured, spilling on Richard’s expensive jacket.

“You stupid fool!” Richard shouted, drunk rage a familiar sound.

Elijah apologized and coaxed him to a side washroom.

Clarara arrived like an answer and blotted the stain.

In the movement of cloth and anger, Elijah’s fingers found the chain at Richard’s neck.

Cheap metal snapped.

The key slid into Elijah’s palm.

“Most of it will come out,” Clarara said.

Richard, oblivious, stumbled back to his guests.

Elijah waited ten minutes, then returned to the study.

The key turned.

Inside, order waited—names, ages, descriptions, punishments.

He did not take the book.

He destroyed its value.

He swapped names, scrambled ages, changed descriptions until the pages no longer told the truth.

He tore out records of his mother, himself, and the five others, folded them, and pocketed them.

He took the gun and the coins—protection and means—and wiped what he had touched.

At 10:15, he slipped back to the kitchen.

The party roared.

The house breathed whiskey and money.

At eleven, he moved to the quarters, shadows as cover, patrol rhythm as guide.

In the cabin, Moses, Samuel, Abigail, Clarara, Hannah, and Ruth waited with bundles of water, food, blankets, tools—the small things that mean life when you have none.

“Dogs?” he asked.

“Sleeping,” Hannah said.

“Horses?” Samuel grinned.

“Running circles in fields they don’t know.”

“We’ve got twenty-five minutes,” Moses said.

“Window’s open.”

“Then we go,” Elijah said.

“Stay close.

Quiet.

Follow me.”

They did not choose the road.

Hunters know roads belong to the people who built them.

Elijah led them east into trees, toward a creek whose cold would hide scent and make dogs useless if any woke.

Behind them, Oakridge glittered and shouted.

Richard raised his glass.

He did not know that the strongest man he owned had dismantled his empire while serving his wine.

At the treeline, Elijah paused and looked back.

He memorized the outline of a place that had shackled his mother.

He turned north and began.

They walked through night, water numbing feet, hope warming lungs.

Ruth and Abigail slowed, pain layered in years.

They did not stop.

By dawn, they had gone fifteen miles.

Elijah found brush thick enough to hide eight people and told them to rest, to drink, to breathe.

“When will they know?” Clarara asked.

“Sunrise,” Elijah said.

“Party won’t end ‘til three.

Checks won’t happen until dawn.

We have six or seven hours.”

“They’ll try horses,” Samuel said.

“They’ll fail.”

“They’ll try dogs,” Hannah said.

“They’ll sleep.”

Ruth touched her son’s hand and looked at him like mothers do when they see a boy has become a man without breaking the part that knows home.

“You did it,” she said.

“I learned from you,” Elijah said.

“And from Papa.”

They moved by night and hid by day.

They stayed off roads, followed creeks, cut through briars that abrade skin but confuse men on horses.

Three days brought them into Tennessee.

Six brought them to a farm whose owners asked no questions and offered bread and directions, Quakers who believed in something larger than property.

Twelve brought them to Kentucky.

Twenty-three took them over the Ohio River into free soil—cold morning, hearts pounding, eight people who had been called property and now stood in air that refused that word.

Years later, Elijah lived in Canada, old and quiet, with grandchildren who listened to the sound of a hunter making the past into a story that keeps a truth alive.

He told them about acting weak, about serving at a party without spilling rage, about keys and locks and ledgers and the way water holds scent the way silence holds power.

He told them about Ruth, about Abigail’s courage, about Samuel’s steady anger, about Clarara’s eyes and Hannah’s calm hands, about Moses’s knowledge.

He told them why hunters study before they move.

He told them the part he wanted them to remember most: people who enslaved others teach a lie—that there is no power in the enslaved.

The lie breaks when someone refuses to accept it.

Intelligence, bravery, unity, patience—those are tools as real as guns.

When used carefully, they change fate.

Richard Marlo never recovered.

Losing eight people cost money.

Losing face cost more.

Neighbors whispered that he had been fooled by a man he called simple.

Over time, the story grew—a giant slave who wasn’t a slave at all, a hunter inside a cough, a mother led out of chains by a son who refused to let fear keep him obedient.

Katherine never forgave herself for ignoring the warning in her own eyes.

She had seen something sharp beneath Jonas’s surface and chose to call it nothing.

She carried the knowledge that she had been right and had done nothing with it.

Elijah lived to see slavery end.

He watched a country burn and rebuild.

He taught his children to read under a lamp that did not belong to a master.

He braced his grandchildren’s small shoulders and told them not to believe anyone who says timing is everything.

Preparation is everything.

Courage is everything.

Community is everything.

On the night they left Oakridge, eight people did more than escape.

They made a choice, and the choice itself became a kind of freedom no law can erase.

They proved they were not objects to be owned.

They proved that a hunter’s mind, a mother’s strength, and a small group’s trust can pierce systems designed to make people forget what they are.

They chose freedom.

That choice is heavier than iron and lighter than breath—and it lasts.

News

The most BEAUTIFUL woman in the slave quarters was forced to obey — that night, she SHOCKED EVERYONE

South Carolina, 1856. Harrowfield Plantation sat like a crowned wound on the land—3,000 acres of cotton and rice, a grand…

(1848, Virginia) The Stud Slave Chosen by the Master—But Desired by the Mistress

Here’s a structured account of an Augusta County case that exposes how slavery’s private arithmetic—catalogs, ledgers, “breeding programs”—turned human lives…

The Most Abused Slave Girl in Virginia: She Escaped and Cut Her Plantation Master Into 66 Pieces

On nights when the swamp held its breath and the dogs stopped barking, a whisper moved through Tidewater Virginia like…

Three Widows Bought One 18-Year-Old Slave Together… What They Made Him Do Killed Two of Them

Charleston in the summer of 1857 wore its wealth like armor—plaster-white mansions, Spanish moss in slow-motion, and a market where…

The rich farmer mocked the enslaved woman, but he trembled when he saw her brother, who was 2.10m

On the night of October 23, 1856, Halifax County, Virginia, learned what happens when a system built on fear forgets…

The Slave Who Tamed the Hounds — And Turned Them on His Masters

Winter pressed down on Bowford County in 1852 like a held breath. Frost clung to bare fields. Pines stood hushed,…

End of content

No more pages to load