In 1845, the wealthiest man in Mississippi made a purchase that defied the laws of economics.

And then he committed an act that defied the laws of nature.

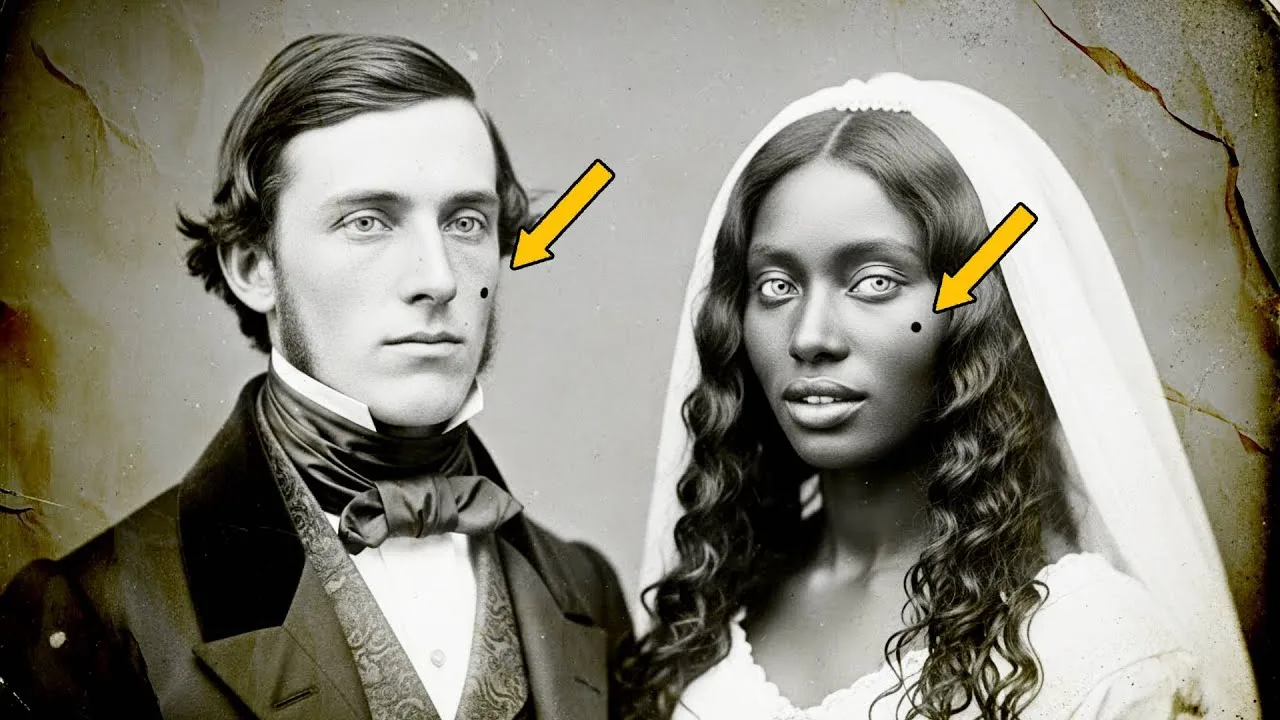

He married a woman who was his exact physical double.

Not his twin, not his cousin, but a stranger he bought at a private sale.

For four years, their life was a fairy tale of wealth and beauty until the children were born.

These children were described as terrifyingly perfect.

And but while they thrived in the nursery, everything else on the plantation died.

The crops turned to gray dust.

The livestock went mad.

The ground itself rejected them.

It was as if nature was trying to scratch this family off the face of the earth.

What finally destroyed the Bowmont estate wasn’t a war or a disease.

It was a single sealed letter postmarked from Paris 20 years earlier that arrived on the very morning the master planned to legalize his legacy.

When that seal was broken, the silence in the room was so heavy it reportedly stopped the clock on the mantelpiece.

Tonight we are opening the sealed files of the Baron Bluff.

We are investigating the biological mirror that drove a rational man to madness.

This is the story of the master who fell in love with his own reflection and paid the ultimate price.

Welcome to the Bowmont mystery.

Before we unseal the documents that Natchez tried to forget, I need you to join our circle of truth seekers.

If you believe that history holds lessons that must not be ignored, subscribe to Before the Story and hit that notification bell.

We are building a community dedicated to excavating the past’s most difficult narratives.

If this investigation keeps you watching, like this video to help the algorithm share this history with the world.

And I have a question for you tonight.

Let us know in the comments from what part of the world you are joining us to uncover this story.

This history belongs to no single nation but to the darker heritage of humanity itself.

Now let us open the gates to the Bowmont estate.

The year was 1845 and Nachez sat at top the bluffs of the Mississippi River like a crown jewel of the American South, a city where cottonwealth had constructed a localized version of Olympus.

It was a society governed by rigid invisible lines.

lines between the classes, lines between the old French aristocracy and the new American money, and lines between the public performance of virtue and the private reality of vice.

In this hermetic world, the Bowmont estate was an anomaly even before the tragedy began.

While other plantations sprawled outward, hungry for land, the Bowmont holding was vertical, dominated by a mansion perched precariously close to the cliff’s edge, as if looking down upon the river with disdain.

The patriarch, Elias Bowmont, had died in the winter of 1844, a man known for his solitary habits and his refusal to allow visitors into the inner sanctum of his home.

He died interstate, leaving behind no will, no instructions, and a fortune that seemed to have no clear purpose other than its own accumulation.

The vacuum left by Elias was filled in the spring of 1845 by the return of his only acknowledged son, Charles Bowmont.

At 25, Charles was a creature of the old world rather than the new, having spent the last decade in the salons of Paris and the lecture halls of the Saon.

Portraiture from the era depicts him as a man of striking almost feminine beauty with pale gray green eyes that would become the central obsession of local gossip.

He returned to Nachez not with the ambition of a planter, but with the arrogance of a doofa claiming an absolute throne.

He spoke English with a clipped foreign affectation and showed an immediate open contempt for the rough huneed manners of his Mississippi neighbors.

To Charles, Nachez was a stage that was too small for his intellect.

Yet it was the only kingdom he possessed.

The documentary evidence from this period, primarily the terrified letters of the estate’s overseer, Mr.

Silas Gentry suggests that Charles had no interest in the agricultural realities of his inheritance.

The cotton fields were left to the management of subordinates, while Charles focused entirely on the mansion itself.

He ordered the windows draped in heavy velvet to block the relentless Mississippi sun, creating a permanent twilight within the house.

He imported mirrors from Venice, crates of them, installing them in the hallways, the parlor, and the bed chambers, transforming the interior into a labyrinth of reflections.

It was as if he sought to multiply his own image to create a world where he was never truly alone, yet never in the company of anyone who was not in some way himself.

This narcissism was not merely a personality quirk.

It was the foundational rot of the tragedy to come.

Charles preached a philosophy of aesthetic purity, a belief he had picked up in the fringes of European radicalism, which held that beauty was the only true morality, and that the superior man was exempt from the laws of church and state.

He wrote in his personal journal, which was recovered decades later from a lawyer’s safe, that the common laws of men are fences for cattle, not guidelines for lions.

This dangerous hubris blinded him to the reality of the ground he stood upon.

He believed he could curate his life like an art collection, selecting only the elements that pleased him and discarding the rest, unaware that biology has laws that cannot be rewritten by philosophy.

The atmosphere on the bluff during that first summer of Charles’s return was described by neighbors as oppressive.

The heat was unusual, a suffocating blanket of humidity that kept the city in a state of agitation.

Birds reportedly stopped nesting in the oak trees surrounding the Bowmont Manor, and the horses in the stables were prone to inexplicable panics.

The servants, many of whom had served Elias for decades, moved through the house in silence, sensing a shift in the metaphysical architecture of their world.

They whispered that the young master brought a cold fire with him, a presence that felt less like a living man and more like a haunting that had not yet happened.

Into this environment of tension and mirrors, the first crack in the social order appeared not with a bang, but with a transaction.

The financial ledgers of the Bowmont estate show a significant withdrawal of funds in late April, a sum large enough to purchase a thousand acres of prime bottomland.

But Charles did not buy land.

He did not invest in machinery or stock.

Instead, he turned his attention to the human market, but not the one that fueled the economy of Nachez.

He sought something specific, something that did not exist in the common cataloges of the trade.

He was looking for a reflection, though he did not know it yet.

The legal structure of Mississippi in 1845 was a complex web of property rights and human subjugation, a system that Charles viewed with detachment.

He did not see himself as a master in the traditional sense.

He saw himself as a collector.

He dismissed the existing household staff, claiming they were relics of a grotesque past and began the process of curating a new domestic sphere.

It was this purge that isolated him further from the community, cutting the last ties to the generational knowledge that might have warned him of the danger lurking in his own history.

Elias Bowmont had died with his secrets locked in his heart, assuming that silence would protect his son.

But silence in the Gothic South is never empty.

It is merely a container for things that are fermenting.

Charles walked through the empty rooms of his inheritance, seeing only the surface, unaware that the foundation was built over a fault line of hidden lineage.

He was a man walking blindfolded toward a cliff, guided by his own vanity.

The stage was set.

The house of mirrors was polished.

The master had returned.

All that was missing was the mistress.

And when he found her, the tragedy would not be that she was a stranger, but that she was the one soul on earth who was exactly terrifyingly familiar.

The Baron Bluff was about to claim its first victims, not through violence, but through a closeness so perfect it was a crime against nature itself.

The first anomaly appears in the commercial records of a private estate sale in May 1845, held not at the public auction block, but in the hushed parlor of a deceased judge in New Orleans.

Charles Bowmont traveled down river specifically for this event guided by a tip from a French art dealer.

The item in question was listed simply as lot 7 rose female age 19 domestic convent raised.

There was no description of her labor skills, no mention of her health or temperament.

The only descriptor was a phrase that stands out in the brutal lexicon of the trade.

warranted untouched.

May this chilling bureaucratic euphemism signaled a human being valued solely for an abstract purity, a commodity for a connoisseur rather than a planter.

Charles paid $4,000 for her.

To put this sum into perspective, a strong fieldand in 1845 might command $1,000.

A skilled blacksmith perhaps $2,000.

$4,000 was a king’s ransom, a price that defied all economic logic of the era.

It was an emotional purchase, an acquisition driven by an immediate, visceral recognition.

Witnesses at the private sale later testified that when Charles saw Rose, he did not examine her as one would property.

He simply stopped, went pale, and signed the bankdraft without asking a single question.

It was as if he had found a lost possession rather than purchased a new one.

The return journey to Nachez marked the beginning of the public scandal.

By custom and law, enslaved people traveled in the cargo holds of steamboats or on the open decks.

Charles Bowmont, however, booked a private cabin for Rose.

He walked her up the gangplank, not in shackles, but with her hand resting lightly on his forearm, a gesture of closeness that caused heads to turn and whispers to ignite along the levy.

She was dressed in simple gray wool, her head covered, but those who caught a glimpse of her face described a haunting serenity, a stillness that mirrored Charles’s own arrogant calm.

Upon arriving at the manor, the violation of social norms escalated from eccentricity to transgression.

Charles did not assign Rose to the servants’s quarters or even to a room near the kitchen.

He installed her in the guest suite of the east wing, a set of rooms with a balcony overlooking the river, furnished with the finest imports from his father’s time.

This was a space reserved for visiting dignitaries, not for a woman purchased at sale.

The household staff, sensitive to the intricate hierarchies of their world, were paralyzed by confusion.

Was she a servant, a mistress, a guest? Charles gave no explanation, only an order that she was to be addressed as Madmoiselle Rose, a title that conferred a devastating ambiguity.

Rose herself is a ghost in the early documentation.

She left no letters and because she was legally property, she appeared in no sensus as a person.

We must reconstruct her through the gaze of others.

The overseer gentry noted in his log book, “She moves without sound.

She speaks French with a dialect that matches the masters.

She does not work.

She sits in the garden and waits.” This waiting is a recurring motif in the testimonies.

Rose did not seem surprised by her elevation.

She seemed to accept it as a destiny foretold.

There was no gratitude, no fear, only a profound silent recognition of her place in this specific house.

The physical resemblance between master and servant was the first thing that unsettled the few visitors Charles allowed.

Both possess the same pale high forehead, the same sharp aqualine nose, and most disturbingly the same gray green eyes that seem to change color with the river’s light.

In a society obsessed with racial classification, Rose was a pass blanc, light enough to pass for white, yet legally bound by the laws of the South.

But the resemblance went beyond race.

It was familiar.

They looked like siblings, a fact that observers noted with a shudder, attributing it to the uncanny luck of Charles finding a companion who suited his vanity so perfectly.

Within a week, Charles began dining with her.

This was the crossing of the Rubicon.

In the antibbellum south, the dining table was the altar of the family, the space where hierarchy was performed.

To seat an enslaved woman at the head of the table served by other enslaved people was to dismantle the entire ideology of the plantation.

Charles did it with relish.

He dressed her in silks ordered from New Orleans, adorned her with his mother’s jewelry, and spent hours in conversation with her, speaking only in French, excluding the rest of the household from their private world.

The town of Nachez began to close its doors to Charles Bowmont.

Invitations to balls ceased.

Business deals were rooted through intermediaries.

The polite society of the Bluffs could tolerate the private exploitation of the enslaved.

It was the open secret of the South.

But they could not tolerate the elevation of that exploitation to the status of romance.

Charles was not treating Rose as a mistress.

He was treating her as an equal.

And in 1845 Mississippi, that was a more dangerous heresy than cruelty.

Yet amidst the scandal, there was a palpable sense of peace within the mansion’s walls.

For the first time since his return, Charles seemed settled.

The nervous energy that had driven him to drape the windows subsided.

He had found his mirror.

He had completed the collection.

The tragedy was that he believed he was building a future when in reality he was locking the door on a trap set 20 years ago by his own father.

The anomaly was not just in their behavior.

It was in their blood.

Singing a song of recognition that neither of them knew the lyrics to, only the melody.

The scandal metastasized into horror in the summer of 1845 when Charles Bowmont did the unthinkable.

He demanded a wedding, not a quiet, informal arrangement, but a sacrament.

He summoned Father Sterling, the aging Jesuit priest who presided over the parish of St.

Mary to the mansion.

Sterling, whose church held a significant mortgage financed by the Bowmont estate, found himself in a moral vice.

The diaries of the priest kept in the diosis and archives reveal a man trembling before a parishioner who held the power of ruin in one hand and a blasphemous request in the other.

Charles wanted a Catholic marriage ceremony for himself and rose.

Father Sterling argued the law.

The state of Mississippi forbade marriage between the races.

It was a felony, a nullity, a crime.

Charles countered with his own twisted theology, “The state does not own my soul, father,” he is recorded as saying.

And in the eyes of God, are we not all souls? It was a manipulation of faith that cornered the priest.

Sterling eventually capitulated, agreeing to a private blessing that would have no legal standing, but would satisfy Charles’s obsession with legitimacy.

He performed the right in the mansion’s library with the heavy velvet curtains drawn against the midday sun.

The ceremony described in Sterling’s confession was suffocating.

There were no guests, no witnesses other than the silent, terrified house servants standing in the shadows.

As Charles and Rose knelt on the Persian rug, the priest noted the terrifying symmetry of their profiles.

It was like marrying a man to his own reflection.

Sterling wrote, “When they joined hands, the air in the room grew heavy, as if the house itself was holding its breath.

The moment he pronounced the benediction, a gust of wind reportedly slammed the balcony doors open, extinguishing the candles.” Charles laughed, calling it a sign of approval.

Sterling feared it was a departure of grace.

Following the ceremony, the isolation of the Bowmont estate became absolute.

Charles formerly withdrew from the cotton exchange.

He stopped attending Sunday mass, claiming that his home was now his church.

The couple retreated into a domestic routine that was frighteningly hermetic.

They were seen walking the grounds at twilight, always touching, always whispering.

They read to each other in the garden, played duets on the pianoforte.

Rose had been trained in music at the convent and existed in a bubble of impossible happiness that unnerved everyone who witnessed it.

But while the couple thrived, the land began to revolt.

The anomaly spread from the house to the soil.

That autumn the cotton crop on the Bowmont plantation failed.

It did not succumb to bullw weevil or blight.

The plant simply withered, turning gray and brittle as if the earth had been salted.

Neighboring plantations had record yields, but the Bowmont fields were a patchwork of rot.

The enslaved field hands, superstitious and observant, began to bury charms at the edge of the fields, whispering that the unnatural union in the big house had poisoned the ground.

Inside the mansion, the mirrors seemed to multiply.

Charles ordered more reflective surfaces installed, covering entire walls in the dining room.

He was obsessed with capturing every angle of their life together.

He commissioned a painter from New Orleans to create a double portrait, but the artist fled after 3 days, claiming he could not find the line where the man ended and the woman began.

The unfinished canvas was later found slashed in the attic, a blur of gray green paint that looked less like two faces and more like a single distorted scream.

The accumulation of strange events continued.

Birds were found dead on the balcony every morning, having flown into the glass doors.

The water in the systems turned brackish and metallic, forcing the household to haul water from the river.

The very structure of the house seemed to groan with doors refusing to latch and floorboards warping despite the lack of dampness.

It was a classic manifestation of the Gothic environment, reacting to moral transgression.

Nature rejecting the presence of the taboo.

Yet amidst this decay, Charles and Rose were radiant, their health improved.

They seemed to glow with a terrifying vitality, feeding off each other while the world around them sickened.

Charles wrote in his journal, “We are an island of perfection in a sea of mediocrity.

Let the cotton die.

We are cultivating a higher crop.

He was referring to Rose’s pregnancy announced in the winter of 1846.

The news sent a shock wave through the county.

A child born of this union would be a living paradox, illegitimate by law, mixed heritage by definition, yet heir to the largest fortune on the river.

The accumulation of evidence points to a singular disturbing truth.

The universe was screaming a warning that Charles refused to hear.

Every dead bird, every withered plant, every uncomfortable glance from the priest was a signpost pointing toward the abyss.

But Charles saw only the reflection of his own desires.

He believed he had conquered the social order, unaware that he was engaging in a biological gamble where the house always wins.

The impossible sacrament had been performed and now the reckoning was gestating in the womb of the woman he called his wife.

By 1847 the silence radiating from the Bowmont estate had birthed a thousand rumors.

The town of Nachez unable to see inside the walls created its own mythology to explain the anomaly.

The most prevalent hypothesis found in the diaries of the local matrons and the sermons of rival ministers was one of dark magic.

The community hypothesized that Rose was not a simple convent girl, but a practitioner of ancient rituals, a siren sent from the deeper swamps to bewitch a rational man.

They needed a supernatural explanation because the alternative that a white aristocrat had genuinely fallen in love with a slave was too threatening to their social order.

This dark magic hypothesis was fueled by the secrecy.

The delivery boys from the market reported that Rose never spoke to them, only stared with those unsettling Bowmont eyes.

They claimed she walked without bending the grass, that she could silence a barking dog with a raised hand.

These were the embellishments of fear, but they served a social function.

They cast Charles as a victim, a man ins snared rather than a man choosing his own destiny.

It was a comforting lie for the white populace, absolving one of their own by blaming the influence of the other.

However, a darker, more clinical hypothesis emerged from the journals of Dr.

Aris Thorne, a physician who had briefly treated Charles for a fever in 1846.

Thorne, a man of scientific temperament, rejected the supernatural.

He noted in his private case book, “It is not magic that binds them, but a shared pathology.

They exhibit the shared delusion of twins who have created a private language.

It is a foyadur, a madness of two.

Thorne was the first to document the sublime narcissism of the couple.

He observed that they did not look at each other with the hunger of lovers, but with the recognition of self.

He loves her because she is him, Thorne wrote, and she loves him because he is the only mirror that reflects her true face.

This hypothesis of narcissistic collapse suggests that Charles was mentally unstable long before he met Rose.

His obsession with his own lineage, his disdain for the outside world, and his aesthetic rigidity predisposed him to fall in love with his own reflection.

Rose, raised in the isolation of a convent, and then thrust into servitude, found in Charles the only safety she had ever known.

Their bond was not forged in magic, but in trauma and ego.

They were two broken halves of a whole trying to fuse back together, unaware that the hole was a biological impossibility.

The servants, primarily the older women who worked the kitchen, held a third hypothesis, one that was whispered only over the washing tubs.

They believed in the concept of blood memory.

They whispered that the ancestors were angry.

They didn’t know the specific truth of the sibling bond, but they sensed the wrongness in the air.

Lineage don’t mix with lineage like that.

One recorded testimony from a WPA interview in the 1930s recalls a former resident saying, “It curdles.

They believed the dead master, Elas, was haunting the grounds, furious that his secret was being paraded in the master bedroom.

These competing theories, magic, madness, and haunting, swirled around the closed gates of the estate like fog.

Charles, oblivious or indifferent, reinforced them all by his behavior.

He ordered a high brick wall constructed around the perimeter, topped with iron spikes.

He fired the remaining local staff and imported silent non-English-speaking servants from the Caribbean, ensuring that no gossip would leak out.

He was building a fortress for his family, a hermetically sealed kingdom where his hypothesis that love transcends law could be proven right.

But the most chilling document from this period is a letter Charles wrote to a former professor in Paris.

In it, he boasts, “I have conducted an experiment in happiness that defies the small minds of this continent.

I have found the perfect equation.” He viewed his life as a scientific triumph, a proof that he was a superior being.

This intellectual arrogance was the armor that prevented him from seeing the cracks in the glass.

He was so busy proving the world wrong that he failed to ask why the world was so frightened.

The closed gate became a symbol for the entire county.

It represented the boundary between the known world of laws and traditions and the unknown world of the bowonts.

Inside the experiment was proceeding.

Rose was heavy with child.

The mirrors were polished.

The hypothesis of the town was about to be tested against the reality of flesh and blood.

And when the children arrived, they would shatter every theory, presenting a puzzle that no superstition could explain away.

In the winter of 1847, the closed gate opened briefly to admit Dr.

Thorne.

Rose was in labor.

The birth was difficult, lasting 20 hours.

A physical ordeal that the doctor described as a battle between life and the reluctance of the womb to release its prize.

When the cries finally echoed through the silent mansion, they were duel.

Rose had delivered twin boys.

Charles named them Jeanluke and Pierre.

Names that invoked his beloved France and rejected the Anglo traditions of Mississippi.

The birth of the twins fractured the social reality of Nachez because of one undeniable fact.

They were physically perfect.

In the racist pseudocience of the 19th century, the mixed heritage child was often expected by prejudiced observers to be inferior.

Society relied on this belief to justify its hierarchy.

But Jeanluke and Pierre were specimens of terrifying health.

They were fairs skinned with hair like spun gold and the unmistakable piercing gray green eyes of the Bowmont line.

They were not just healthy.

They were hypervital, growing faster and stronger than the legitimate children of the town’s elite.

This impossible perfection was an insult to the natural order as the town understood it.

How could a taboo produce such beauty? The cognitive dissonance rippled through the community.

The church ladies whispered that darker forces disguised their spawn as angels.

The men at the cotton exchange grumbled that Charles was breeding a new race to replace them.

The existence of the twins challenged the biological justification of the hierarchy.

If the children of a master and a servant could be the most beautiful children in the county, then the lie of blood superiority was exposed.

While the boys thrived, the environment around them continued its aggressive decay.

The winter of 1847 was the coldest on record.

The ornamental gardens Charles had planted froze into black sludge.

The river rose and flooded the lower fields, drowning the few remaining livestock.

It was a stark biblical contrast.

The radiant golden children playing in a nursery of silk while outside the window the world turned to ice and mud.

The supernatural realism of the situation was undeniable.

The life force of the land was being sucked into the house to sustain the unnatural lineage.

Charles’s reaction to fatherhood was manic.

He paraded the infants around the library, holding them up to the mirrors, whispering, “See, we continue.” He saw them not as individuals but as extensions of his own ego, proofs of his perfect equation.

He refused to have them baptized in the church, fearing the public gaze, and instead performed his own ritual of naming in the garden, an act that Father Sterling condemned as a pagan christening.

This further severed the family from the spiritual protection of the community.

The social fracture deepened when Charles began to speak of inheritance.

He let it be known that he intended to leave everything, the land, the money, the house, to Rose and the boys.

This was a direct threat to the legal stability of the region.

If a white man could leave his fortune to his illegitimate children, the entire economic system of inheritance was at risk.

The distant cousins of the Bowmont family, led by a man named Reginald Bowmont in Virginia, began to take notice.

Letters were exchanged.

Lawyers were consulted.

The perfect sons were not just a scandal.

They were a financial liability.

Inside the nursery, the anomaly of the twins became more specific.

They did not cry like normal infants.

They were quiet, watchful, observing the world with an intensity that unsettled the nannies.

They seemed to share a hive mind, moving in sync, sleeping at the exact same intervals.

Doctor Thorne noted, “They are less like two children and more like one soul, divided into two vessels.” This biological mirroring was the ultimate manifestation of the close-kin root.

The genetic diversity had been narrowed to a singular repeating point.

The fracture was now complete.

The Bowmont estate was an alien organism within the body of Nachez.

The town wanted it exised.

The church wanted it cleansed, and the law wanted it seized.

Charles stood alone against them all, armed only with his arrogance and his beautiful, impossible sons.

He believed he had won the game of genetics.

He did not know that he was playing against a stacked deck and that the dealer, his dead father, had left a card up his sleeve that would turn the perfection into a curse.

As the twins approached their second birthday in 1849, the cracks in the domestic perfection began to manifest through Rose.

Until this point, she had been the silent, compliant muse, the calm center of Charles’s storm.

But the human psyche can only suppress the truth for so long before it erupts.

The irrefutable evidence of the tragedy did not come from a document initially, but from the behavior of the mother.

Rose began to suffer from night terrors of a specific and disturbing nature.

The servants testimonies gathered in later years describe harrowing scenes.

In the dead of night, Rose would rise from the bed she shared with Charles, walk down the marble hallway in a trance, and weep uncontrollably outside the door of the old master’s study, the room where Elias Bowmont had died.

In her sleep, she did not call for Charles.

She did not call for her children.

She called out a single word over and over in a voice that sounded like a frightened child.

Papa Charles, awakened by her cries, would find her scratching at the wood, her fingernails broken.

He interpreted this through the lens of his own narrative.

He dismissed it as homesickness or a delayed trauma from her time in the convent.

She misses the father figures of her youth, he told Dr.

Thorne, rationalizing the horror away.

He could not hear what the servants heard.

The specific intimate tone of a daughter grieving a parent she was not supposed to know.

It was the subconscious mind rejecting the lie of her identity.

The impact of these episodes on the household was corrosive.

The Caribbean servants, sensing the violation of a deep taboo, began to leave tobacco offerings at the doors to ward off confused spirits.

They knew that when a wife calls for her father in the arms of her husband, the blood is crying out.

The atmosphere in the house shifted from romantic isolation to a frantic, haunted tension.

Rose would wake in the morning with no memory of the night, but her eyes grew hollow, her skin pale.

The mirror was beginning to crack.

Then came the physical evidence.

In early 1849, one of the twins, Pierre, fell while playing and cut his forehead.

The wound refused to clot.

For hours, the blood flowed with a terrifying persistence, defying the bandages.

Dr.

Thorne was summoned.

He managed to stench the bleeding with cauterization, but he noted the anomaly in his journal.

The blood is too thin.

It lacks the agent of binding.

It is as if the water of life has been diluted.

Hemophilia or a similar blood disorder was a known risk of very close breeding.

Though the genetics were not yet fully understood, it was the first biological receipt for the taboo.

Charles refused to accept the diagnosis.

He fired Dr.

Thorne, accusing him of incompetence.

“My sons are perfect,” he roared, banning the doctor from the grounds.

He retreated into denial, convinced that the world was conspiring to find flaws where there were none.

He began to sleep with a pistol on the nightstand, paranoid that intruders were poisoning his children.

The night terrors and the thin blood were irrefutable evidence that the biological check was coming due.

But Charles tore up the bill.

The documentation from this period shows a man unraveling.

Charles’s handwriting in his journals becomes jagged, erratic.

He writes of whispers in the walls and eyes in the portraits.

He begins to suspect Rose of keeping secrets, asking her repeatedly, “Who are you? Who are you really?” It was a question that cut too close to the bone.

He loved her, but he was beginning to fear her, sensing the blank space in her history that matched the blank space in his own.

The impact on Rose was a withdrawal into silence.

She stopped playing the piano.

She stopped walking in the garden.

She became a statue again, watching her bleeding son and her unraveling husband with a tragic knowing resignation.

She was the vessel of the truth, carrying the secret in her very genetic code, waiting for the external world to catch up to the internal reality.

The house was no longer a sanctuary.

It was a waiting room for the executioner.

By late 1849, the external pressures on the Bowmont estate merged with the internal decay to create a total collapse of Charles’s authority.

The legal system, alerted by the cousin Regginald Bowmont, began to probe the validity of Charles’s holdings.

The collapse was documented in the frantic series of wills Charles drafted in a six-month period.

The county courthouse archives contain five separate drafts, each more desperate than the last.

In the first draft, he leaves everything to my wife Rose.

His lawyer informed him this was void.

A slave cannot inherit property and the marriage was not recognized.

In the second, he leaves it to my natural children, Jeanluke and Pierre.

This too was challenged.

Illegitimate children had no claim over white relatives.

In the third, he attempted to emancipate them first, then bequeathed the estate.

The state legislature blocked the emancipation papers, citing moral concerns.

Charles was trapped.

The immense wealth of the Bowmonts, which he thought was his tool, was actually his cage.

He realized that without a legal heir, everything would revert to the distant cousin, leaving Rose and the boys to be sold as assets of the estate.

The horror of this realization drove him to the brink of madness.

He wrote, “We are a closed circle.

No outside influence shall touch us.

If the law will not protect us, I will build a law of my own.

This law of the own manifested in dangerous preparations.

Charles began to liquidate portable assets, gold, silver, jewelry, and sew them into the linings of coats.

He was planning to flee.

He mapped routes to Mexico, to Cuba, anywhere the Napoleonic code might offer them sanctuary.

But his arrogance delayed him.

He wanted one final victory.

He wanted to force the state of Mississippi to acknowledge his sons.

He planned a definitive trip to the courthouse to register the boy’s birth records, believing that his physical presence and his money could bully the cler into accepting the document.

The authority of the church also collapsed for him.

He ceased all tithes to St.

Mary’s.

He mocked Father Sterling in public letters, calling religion the crutch of the loveless.

This hubris stripped him of his last potential ally.

When the crisis came, there would be no sanctuary in the pews.

He had burned the altar to warm his own vanity.

Inside the house, the authority of the father crumbled.

The servants, sensing the end, began to steal small items and vanish in the night.

The closed circle was leaking.

Rose, seeing the desperation in Charles’s eyes, began to pack trunks with a fatalistic slowness.

She knew with the instinct of the survivor that they would never leave Natchez.

She stopped sleeping entirely, sitting by the window, watching the road, waiting for the figure she knew would come.

The draft wills serve as a grim countdown.

They move from the confident legally of a master to the pleading scribbles of a frightened man.

The final draft unsigned ends with the sentence, “I give all that I am to the only part of me that matters.” It was an admission that his family was not separate from him.

They were him.

And to save them, he would have to destroy the very society that refused to mirror him back.

The collapse was total.

Legal, spiritual, and domestic authority had evaporated.

All that remained was the naked force of the secret waiting to be told.

On the morning of October 14th, 1849, Charles dressed in his finest suit, ordered the carriage, and prepared to ride to the courthouse to demand recognition for his sons.

He never made it to the gate.

The past arrived first.

The sun had barely cleared the horizon on that October morning when a solitary horseman rode up the avenue of oaks.

It was Father Sterling.

He was not there to offer a blessing.

He was there as a courier of destruction.

In his saddle bag, he carried a sealed packet that had traveled a labyrinthine route across the Atlantic, gathering dust in dead letter offices from Paris to New Orleans for nearly two decades.

It was the hidden source, the ticking bomb that Elias Bowmont had inadvertently set before his death.

The packet was wrapped in oil cloth and stamped with the seal of the Ursuline Order of Paris.

It was addressed to Msure Elias Bowmont, Nachez, Mississippi, and postmarked 1826.

It had been forwarded to the St.

Mary’s Rectory because the church was the listed contact for the convent’s charitable donations.

Father Sterling had opened it, assuming it was a business matter.

What he read had turned his face the color of ash.

Sterling found Charles in the parlor, standing before the great mirror, adjusting his crevat.

Rose stood nearby, holding the hands of the twins.

The tableau was striking.

The beautiful doomed family frozen in a moment of fragile perfection.

Sterling entered without knocking.

The testimony from the priest’s later confession describes the scene.

I felt like an assassin.

I carried a paper knife that would cut not flesh but the soul.

He laid the packet on the table.

It is from the mother superior, Sterling whispered.

From Paris.

It concerns the child born in 1826.

Charles frowned, confused.

My father had no dealings with convents, he said, reaching for the letter.

Rose went still, her breath hitched.

The blood memory that had plagued her nightmares suddenly crystallized into a conscious thought.

She took a step back, pulling the children with her.

The letter was written in elegant, cramped French.

It detailed the death of a woman named Marie TZ, a seamstress in the Latin Quarter who had been Elias Bowmont’s mistress during his youth.

It spoke of a daughter, Charlotte, born of that union.

It detailed Elias’s decision to take the infant Charlotte to America, to hide her in a convent in New Orleans, and later to bring her to his estate under a false identity to serve as a domestic, never telling her or his legitimate son the truth of her parentage.

He had registered her under the slave name Rose.

The discovery was absolute.

There was no ambiguity.

The dates matched, the names matched.

The physical description of the child, eyes of gray green, the Bowmont mark, matched.

Charles held the paper, his hands trembling so violently that the page rattled like a dry leaf.

He looked at the letter.

He looked at Rose.

He looked at the mirror.

The connection fired in his brain with the force of a gunshot.

He had not found a soulmate.

He had not found a reflection.

He had found his sister.

The attraction, the familiarity, the impossible perfection.

It was all the biological magnetism of shared blood.

The perfect equation was an abomination.

The closed circle was consanguinity.

The hidden source revealed that his entire life’s happiness was a crime against God, nature, and his own identity.

Rose did not scream.

She simply closed her eyes.

The tears that slid down her face were the silent tears of the night terrors finally given a name.

She was Charlotte Bowmont.

She was not a servant.

She was the daughter of the house and she was the wife of her brother.

The discovery stripped her of her false name and handed her a tragedy so heavy it crushed the air out of the room.

The silence in the parlor stretched for an eternity.

The decision for decisive action did not come from Charles.

He was catatonic, destroyed by the revelation.

It came from Father Sterling and the rigid laws of the time.

The priest, having delivered the truth, now had to enforce the consequence.

He stated the reality with brutal clarity.

The marriage is void.

It is not merely illegal.

It does not exist.

It is the ultimate taboo.

The children are products of forbidden blood.

They are illegitimate in the eyes of the church and bastards in the eyes of the law.

Charles collapsed into a chair, vomiting onto the Persian rug.

The physical rejection of the truth was visceral.

His body was repelling the reality of what he had done.

He looked at Rose, at Charlotte, and saw not his beloved, but a monster of his own making.

the narcissism that had fueled their love inverted instantly into revulsion.

He saw his own face in hers and hated it.

The justification for the next action was rooted in the survival of the estate or what was left of it.

Sterling explained that if this truth became public, the mob would not just take the land, they would destroy Charles.

This taboo was the one sin that transcended the racial divide.

It was primal.

To save his life, Charles had to agree to the immediate dissolution of the household.

Rose Charlotte spoke for the first time.

Her voice was steady, the voice of a bowont.

And the children, she asked.

Sterling looked away.

They cannot remain.

They are living proof of the forbidden union.

They must be sent away to the orphanage in St.

Louis.

They will be raised as wards of the church.

Their names will be changed.

Charles did not fight.

The lion who had written that laws were for cattle was now a broken animal cowering before the slaughter.

He nodded.

He agreed to everything.

He agreed to the eviction.

He agreed to the separation.

He agreed to erase them.

His decision was an act of supreme cowardice justified by shame.

He could not bear to look at them because they were the mirror of his own hubris.

The sheriff, summoned by Sterling to execute the property transfer, as the lack of a valid will and heir meant the cousin took possession immediately, arrived at noon.

The decisive action was a quiet, bureaucratic dismantling of a life.

The trunks were unpacked.

The silks were stripped from rows.

She was given a simple dress.

The children were taken from her arms by a wet nurse hired by the parish.

Charles remained in the library, door locked, refusing to say goodbye.

His journal entry from that day consists of a single line written in a shaky hand.

I have looked into the sun and I am blind.

He justified his abandonment as a mercy, believing that his presence would only taint them further.

But the truth was he was saving his own sanity by excising them like a tumor.

The decision was made.

The perfect family was dissolved.

The closed circle was broken.

The action was swift, cruel, and absolute.

By early afternoon, the mansion was a house of strangers, and the Bowmont bloodline was scattered to the winds.

The final primary source of this tragedy is not a letter or a will, but the sheriff’s eviction log dated October 14th, 1849.

It is a dry, callous document that lists the disposal of assets of the Charles Bowmont household.

It records the locking of the gates, the transfer of livestock, and the departure of the occupants.

But amidst the bureaucracy, there is a handwritten note in the margin by the sheriff.

The woman walked out.

She did not look back.

She carried only two papers.

Those papers were the baptismal certificates of Charlotte Bowmont herself and the birth records of her sons which Charles had filled out but never filed.

They were the only proof of her existence as a human being as a bowont.

The interpretation of this moment is the emotional climax of the story.

Rose now Charlotte walking out of the gates of the plantation was not a servant being cast out.

She was a bowont leaving her kingdom.

She walked past the withered cotton fields, past the frozen gardens, past the closed gate.

She was destitute.

She had lost her husband, who was her brother, her home, and her children were being carted away to an orphanage.

Yet the witnesses, the few servants who watched from the road, described her bearing as regal.

She had survived the revelation.

Charles had shattered, but Charlotte had hardened.

The log records that Charles Bowmont left an hour later riding a black horse heading toward the riverboat landing.

He looked aged 20 years in a day.

He carried nothing.

He left the furniture, the mirrors, the velvet drapes.

He left the portrait of the two of them in the attic.

He was fleeing the reflection he could no longer stand to see.

The final source is the silence that fell over the bluff.

The house stripped of its soul stood empty.

The mirrors reflected only the dust moes dancing in the stagnant air.

The impossible secret had been revealed, and the result was the total annihilation of the dream.

The document interprets this not as a legal defeat, but as a moral exorcism.

The land had vomited them out.

Reginald Bowmont, the cousin from Virginia, arrived a week later to claim the prize.

He found the mansion disturbed him.

He wrote to his wife, “The house feels like it is watching me.

The mirrors are everywhere.

I shall have them removed.” He never lived there.

He sold the contents and boarded up the windows.

The interpretation of history is clear.

The house was not a home.

It was a monument to a mistake.

and the only way to cleanse it was to let it rot.

The consequences of the Bowmont tragedy rippled out for decades, documented in scattered records that historians have had to piece together like shards of a broken mirror.

Charles Bowmont did not survive his shame.

Records from New Orleans show a Charles B dying in a flop house in the French Quarter in 1850, less than a year after the separation.

The cause of death was listed as apoplelexi, likely a stroke brought on by relentless self-destruction.

He died alone, surrounded by strangers, far from the mirrors he once loved.

The mansion on the bluff met a fiery end.

In 1860, on the eve of the Civil War, a mysterious fire consumed the structure.

The blaze was so intense it melted the glass of the hundreds of mirrors into the foundation, creating a layer of fused silica and red clay.

Locals whispered it was arson, perhaps committed by Charlotte herself, returning to destroy the scene of the crime, or perhaps by the ghost of Elias.

The site became known as the Baron Bluff, a scar on the landscape where nothing would grow.

But the true legacy lies with the children.

The records of the St.

Louis orphanage show the arrival of John and Peter, two fair-haired boys with gray green eyes.

They were adopted separately, their Bowmont name erased.

However, genetics is a stubborn archavist.

Traces of the family appeared in medical journals in the 1870s.

Cases of blood disorders in young men in Missouri linked to unknown lineage.

The blood continued to tell the story that the law had tried to silence.

And Charlotte, she vanished from the white records of Nachez, but she reappeared in the shadows of history.

A woman matching her description worked as a seamstress in St.

Louis, living quietly, never marrying.

She was buried in a porpa’s grave in 1880.

Among her personal effects, the undertaker found a silver locket containing a lock of golden hair and a scrap of paper with the name Bowmont written in elegant French script.

She had kept the name that destroyed her.

The documented consequences show that while the estate was lost, the secret survived.

The horror of the forbidden union was not that it produced monsters, but that it produced human beings who had to carry the weight of a sin they did not commit.

The legacy of the Bowmonts is a cautionary tale about the dangers of isolation and the terrifying power of blood to find its own no matter the cost.

Today, if you visit Nachez, you will not find the Bowmont mansion on the tour maps.

The city has erased it, preferring the romanticized history of cotton and krenolin to the macab reality of the mirror house, but the baron bluff remains.

Geologists have attempted to explain why vegetation refuses to take root there, citing soil toxicity or drainage issues, but science cannot explain the feeling of heavy watching silence that descends when you stand on that red clay.

The historian’s analysis suggests that the Bowmont tragedy was a glitch in the social programming of the South.

It exposed the fragility of the racial and moral lines the society drew.

It showed that the difference between a master and a slave could be nothing more than a lie told on a birth certificate and that the purity of the bloodline was often a mask for the deepest corruption.

But the open question remains, what happened to the line? The census of 1870 in St.

Louis lists a Charlotte B living with two young men, John and Peter.

And did she find them? Did the closed circle reform in the anonymity of the city? Did the brothers know that their mother was their aunt and their father was their uncle? Or did they live their lives in blissful ignorance, carrying the Bowmont eyes into the future, marrying and having children of their own? Perhaps you are walking down a street today and you pass someone with striking gray green eyes and a pale aristocratic brow.

You might be looking at the descendant of the master and the slave, the impossible children of the barren bluff.

The mirrors are gone, but the reflection walks among us still.

History is filled with secrets that were never meant to be uncovered.

If this story of the Bowmonts chilled you to the bone, you are one of us.

Subscribe to Before the Story to join our investigation into the shadows of the past.

Click the video on your screen right now to discover another family secret that changed history forever.

The archives are open and the truth is waiting.

See you in the next dark chapter.

[Music]

News

The Truth Behind This 1904 Portrait of a Boy and His Toy Is More Macabre Than Anyone Expected

The truth behind this 1904 portrait of a boy in his toy is more macob than anyone expected. The March…

It Was Just a Wedding Portrait — Until You Noticed What the Bride Was Hiding Behind Her Back

It was just a wedding portrait until you noticed what the bride was hiding behind her back. The air inside…

The Whitaker Girl – The Photograph of a Sleeping Child (1863)

In the humid summer of 1863, amid the whispering cyprress and heavy air of southern Louisiana, a photograph was taken…

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel — until now

This 1920 portrait holds a mystery that no one has ever been able to unravel until now. The basement archive…

This 1885 Portrait of Two Miners Looks Proud Until You Notice The Lamp Numbers

This 1885 portrait of two minors looks proud until you notice the lamp numbers. This 1885 portrait of two minors…

This 1906 Workshop Portrait Looks Busy Until You See The Chalk Mark on Their Boots

This 1906 workshop portrait looks busy until you see the chalk mark on their boots. At first glance, it seems…

End of content

No more pages to load