They said the courthouse had never held so many people.

The air felt like wet wool—heavy with perfume, sweat, and the sour tang of tobacco.

Every bench was jammed tight: merchants in stiff collars, farmers in worn coats, ladies with veils and lace gloves pressed against their noses.

Shoulders touched.

Men packed the standing room in back, craning for the promised spectacle.

Up front, beneath tall windows and peeling whitewash, the defendant’s rail sat waiting.

Inside stood a man in iron.

Chains at his ankles rattled when he shifted, the sound sharp in the hush.

His wrists were cuffed, metal biting into dark skin scarred by old rope burns.

The thin cotton shirt thrown over his broad shoulders did nothing to hide strength.

He held his head high anyway, jaw set, eyes steady—dark as rivers after a storm.

His name was Elias.

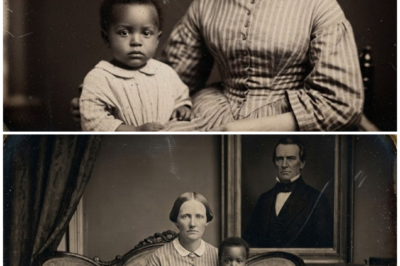

At his side stood a girl the town thought it knew.

Clara Whitfield, daughter of Judge Nathaniel Whitfield, wore plain dove-gray muslin and a severe chignon that exposed a white childhood scar at her temple.

She looked like candle wax left too near a hearth—pale and drawn, lips pressed so tight the color had fled—only her eyes refused to dim.

They burned, blue and feverish, fixed on the empty judge’s bench.

Her hands weren’t chained, but she gripped them together until her knuckles blanched.

On her left ring finger, the thing everyone wanted to see caught the light: a thin, irregular band of black iron.

Ugly, badly forged—something any white woman in the room would have tossed—and yet it held the town like a hand at its throat.

“Quiet,” the bailiff snapped, staff knocking the floor, and the noise settled into a simmering hush.

The judge’s bench was still empty.

The tall walnut chair loomed like an altar awaiting its priest.

“He’s late,” someone whispered.

“He should recuse himself,” another muttered.

“How can he judge his own daughter?”

“Because he’s Judge Whitfield,” came the reply.

“Who else could judge madness like this?”

The clock ticked above the rear doors—each second a slow nail driven into wood.

Clara stared at the empty bench.

The crest of the carved eagle cast a curious shadow on cracked plaster.

She remembered sitting at the back of this room as a child, feet not touching the floor, worshiping her father as he dispensed justice in a booming baritone.

The side door creaked.

A thousand eyes swung as Judge Nathaniel Whitfield stepped through.

He looked older than the year before—silver in his hair spreading, his ruddy complexion washed to sallow gray, black robe looser on shoulders as if some inner scaffold had been eaten away.

But his walk stayed steady as he mounted the dais.

He kept his eyes off the gallery, off the rail, off his daughter—moving through a tunnel made of will alone.

“Court is now in session,” the bailiff announced.

“The Honorable Judge Nathaniel Whitfield presiding.”

Nathaniel sank into his chair.

For one naked instant, his gaze flicked to the rail—glanced off Elias with a flinch—then locked on Clara.

The impact nearly buckled her knees.

There was no warmth, no softness, no echo of the man who had once lifted her onto his knee and read from the family Bible.

He looked at her the way he looked at defendants whose guilt he had already decided.

“Bring the charges,” he said—voice level and crisp as ever, cracked only to ears that had listened eighteen years.

The prosecutor stepped forward—Joseph Cartwright, slick hair, mouth perpetually puckered as if something foul lived beneath his nose.

Ambitious, well-born, eyes gleaming with the knowledge he was about to make a name on someone else’s ruin.

“Your honor,” he said, bowing.

“The Commonwealth brings charges against the property known as Elias—belonging to your honor—and against Miss Clara Whitfield, your honor’s daughter, for miscegenation, moral corruption, and”—he savored it—“the attempted subversion of the legal order of this county by entering a so-called marriage in direct violation of statute and moral law.”

A murmur rolled like thunder.

Cartwright turned toward the rail, lips curling.

“Let the record show the white female defendant is present and adorned with an iron band upon her ring finger, which she persists in calling a wedding ring.” He pivoted, voice oiled.

“Let the record also show that the negro in chains beside her is the subject of this so-called union.”

He made union sound obscene.

Nathaniel’s grip whitened on the chair arms; for a second, his fingers trembled.

“Proceed,” he said.

Cartwright addressed jury and crowd at once.

“We are here to consider an abomination.

A young woman raised in a house of law has elected to throw in her lot with a slave—not merely to lie with him, as animals sometimes stray, but to claim she has married him.” He sneered.

“That property—cattle—might be her husband.

That a piece of stock from your honor’s stables could be raised to the dignity of a white man.”

A sharp laugh cut the room; someone hissed; a woman emitted a gagging sound behind lace.

Clara stared ahead and remembered another night: rain on tin, candle light across rough boards, iron forged and tied around her finger by shaking hands.

Elias’s voice whispering vows into dark—throat tight on words neither had ever been allowed to name.

Husband.

Wife.

She held those words inside like a shield.

Elias stood very still.

If Cartwright’s words cut, his face didn’t show it.

Only a small muscle ticked at his jaw when “creature” slid off the prosecutor’s tongue.

“Can a white woman marry a negro slave?” Cartwright barked.

“Can a daughter take her father’s property and call it her husband? The law says no.

Common sense says no.

God says no.

Miss Whitfield says yes.”

He let the jury savor that.

“Whispers already call this romantic”—he spat the word—“some enchantment of youth.

Today we ask the court not only to punish wickedness but make an example—to remind every soul in this county that our laws are granite, not clay.”

He bowed.

“The prosecution rests its opening.”

“Very well,” Nathaniel said, eyes pinned to papers.

“We will establish the facts.”

Clara almost laughed.

Facts.

Her mind reeled backward—away from the courtroom, into the yard behind her father’s house, into the slice of shade by the tack room where she found him reading.

She had escaped a parlor full of planters with sweat rings on collars and sons with hungry hound eyes.

Her father had motioned subtly—smile, pour coffee—pretend not to feel their appraisal.

When one leaned close and murmured that a judge’s daughter would make an obedient wife, something flared inside her—small, hot, dangerous.

She set the pot hard, pleaded a headache, and left.

She walked past wash line and smokehouse, letting anger drain.

That was when she saw the man beneath the lean-to roof, lips moving soundlessly, finger tracing lines on a book.

He snapped the cover closed, half rose—caught.

Up close, she saw he was tall—very tall—shoulders filling the narrow shade, muscles bunching beneath thin cotton.

But what struck her was the flash in his eyes.

Intelligence, quick and wary.

“Miss Whitfield,” he said, dipping his head.

“Beggin’ your pardon, ma’am.

Didn’t hear you coming.”

“What are you reading?” she asked.

He hesitated—the fight visible—always answer slow.

“A book, miss.”

“Yes, I see that,” she said, unable to help it.

“What kind?”

He wet his lips.

“Law, miss.

Old case records.

From the courthouse.”

Her heart jolted.

“Where did you get them?”

“Judge, ma’am,” he said carefully.

“Pages he don’t need.

I keep papers in order.

When he’s done, he lets some go.”

“Practice what?” she asked.

He looked at her then—really looked—and she felt as if she had stepped into deeper water.

“Reading, miss,” he said.

“And remembering.”

“You can read,” she whispered.

Pride flickered—fear buried it fast.

“Yes, ma’am.

Judge taught me some—help him with his papers.”

Her father had taught a slave to read—her father who rapped her knuckles for stumbling children’s lines.

The irony cut like glass.

“They say I got a good head,” Elias added, tapping his temple.

“I hear a case once—I don’t forget.

Names, dates.

What was said.”

“Valuable,” her father would say, chuckling—sharp as a tack—like praising a favored hound.

“What’s your name?” she asked.

“Elias, miss.”

She had heard it before—“Send Elias”—but never pinned it to a face.

Now she saw flesh and sweat and eyes that saw too much.

“Do you…understand what you’re reading?” she asked.

“Yes, miss.

A good deal.” He hesitated.

“The judge speaks it.

I read what the clerks write.”

“Explain a bit?” she pressed—cheeks warm—brazen.

He measured her—then bent.

He showed her how to read curled clerk handwriting, find names buried in Latin.

He pointed at lines about property and contracts—what each meant.

“This here,” he said, tapping a line.

“This where the judge says a man guilty.”

“How can that line make it so?” she asked.

He stared at her.

“Because the judge wrote it.

Folk act like it’s from God.

But it ain’t.

It’s from the judge.”

They moved from words to stories.

He told her about a fight over a boundary fence—one man dead, one poor—one hanged.

He told her about a woman who stabbed a man who came at night.

He showed her the signature at the verdict, the flourish she’d admired as a child.

It looked like a blade now.

“Surely—,” she began—then heard herself.

Surely what? Surely he thought? Surely the law was just?

“The law is what men like your father write,” Elias said.

“Sometimes fair.

Sometimes ain’t.

But always law.”

“Do you ever disagree?” she whispered.

“Often,” he said.

“And do you tell him?”

“Would you?” he asked.

She remembered her father’s dangerous quiet when she questioned a whipping.

“No.”

“Then neither do I,” Elias said.

“I do the papers well, he keeps me near ink, not field.

I whisper if I can: a name, a fact.

Maybe—just sometimes—a man gets lighter punishment.

A child avoids the worst.

It ain’t much.

But something.”

“And you remember,” she said.

“Names don’t blur,” he replied.

They made time in stolen pockets.

She slipped out with a shawl; he tucked case pages in buckets and shirts.

At first their speech was stiff—caution like a third person in the shed.

Then something else layered between—trust, and the knowledge that their conversations were a line past which both might fall.

“What is right?” she asked one day, after he told her of a thirteen-year-old sentenced to five years for stealing a horse.

He looked at her.

“Right would be remembering a child is a child—no matter color—and a man’s pride over a horse ain’t worth five years of that boy’s life.”

She laid her hand over his—foolish, unthinking.

He froze.

She pulled back like burned—but the imprint stayed on her palm all night.

It felt like a brand.

The summer pressed down—heat shimmering off red clay road, insects droning, slow movement in the yard, suitors multiplying in the Whitfield parlor.

Joseph Cartwright came with flowers, compliments, speeches about family and duty.

Nathaniel weighed candidates like contracts.

Clara smiled when politeness demanded, whispered her fury into pillows, and went to the carriage house instead.

“My father wants me to marry Joseph Cartwright,” she said one night.

Elias slowed his hands.

“The lawyer.

He likes to talk.

And win.”

“He says order keeps wolves from our door,” she said.

“He says law and marriage are cages we should be grateful for.”

“Men made this,” Elias said quietly.

“Not God.”

“He taught you to read,” she said.

“He did.”

“He calls you valuable.”

“Valuable gets sold,” Elias said without saying it.

“Have you ever thought of running?” she whispered.

“Every day since I can remember,” he replied.

“But old folks and young ones call my name when they’re scared.

The lash don’t care who did the thinking.

It comes down where it’s told.”

“You’re right,” she said.

She was tired of rules that existed to keep her soft while keeping him broken.

“Elias,” she said, voice low, “if the world weren’t like this—if no one wrote the law—if you were free—”

“Stop,” he said—rough now.

“Questions without answers get men killed.”

“I’m not asking about touching,” she said.

“I’m asking about feeling.”

“Yes,” he said finally.

“Wrong kind.”

“Then we are already in danger,” she replied.

“You ain’t,” he said.

“They’ll say you were tempted, tricked.

They’ll blame me.

They always do.”

“Then marry me,” she said.

He stared.

“You know I’m property.

You want to marry your father’s property?”

“I want to marry you.”

“There ain’t a preacher—no license—no paper.”

“Your cases—are they the only truth?” she asked.

“Reverend Moses,” he said reluctantly.

“Old man in cabin three.

Marries folks in the quarters.

It ain’t legal.

But it means something.”

“Then let him marry us,” she said.

“What your father will do—”

“We are already damned in his eyes,” she replied.

“All that’s left is to decide what for.”

He cupped her cheek.

“Meet me tomorrow night,” he said.

“Old oak behind the smokehouse.

If you come—we’ll see if God’s watching.”

She came.

They stood in Moses’s tiny cabin with packed earth and one guttering candle.

The old man’s eyes were milk-clouded; his hands were gnarled roots.

“You sure?” Moses asked Elias.

“Sure in the kind of way that ain’t washed off by the first storm.”

“Yes,” Elias said.

“And you, girl?” Moses rasped.

“You know this weight presses every breath?”

“I do,” Clara said, voice shaking.

“If I don’t, I will belong to a man I do not love.

If I do, I will belong to one I do.

That seems the better madness.”

Moses snorted.

“Ain’t nobody belongs to nobody.

We pass each other back and forth and hope someone holds us gentle while they got us.” He tapped his cane.

“Let’s make your madness holy.”

They joined hands.

Moses muttered scripture half remembered, half remade.

He spoke of love—patient and kind—and dangerous in a world like this.

He pronounced them in the only words that mattered to them—husband and wife, fool and fool, bound anyway.

They kissed: awkward first, then surrendering to heat and the terrifying knowledge that they had just defied the world.

Secrets spread like damp in Whitfield walls.

Elsie—a quiet maid who could melt into rooms—found Clara’s journal tucked under a mattress.

Curiosity and envy and fear mixed; she carried it to Cartwright’s office in town.

Cartwright read, and delight sharpened his smile.

He dropped the journal onto Nathaniel’s dinner table later.

Nathaniel read his daughter’s words—the cabin, the candle, the iron ring—and his expression shattered.

Cartwright offered a way to “save” the judge: a trial to reaffirm law—to show even his own family wasn’t above it.

To control the narrative.

“A private handling,” Nathaniel said—hollow.

“Or be dragged under,” Cartwright answered.

Nathaniel chose the law—chose the theater.

He confined his daughter.

Men took Elias in the night.

He glanced at her dark window—saw a hand at the glass—and lifted his chin.

The trial began as you saw it.

Cartwright painted their love as filth.

Clara wore the iron ring like defiance.

Nathaniel mounted the bench like a man climbing a gallows of his own making.

On the stand, Clara did not flinch.

“I pursued him,” she said.

“I love him.

The law is wrong.” She said aloud what everyone knew—white men’s nights in slave cabins—truths the court struck from record but not from the world.

Elias said he tried to keep distance—that any fault should fall on him.

Cartwright seized and preached civilization built by “men of wisdom.”

“Men like the ones who owned my mother,” Elias said.

“Men who came to cabins smelling of whiskey.”

Nathaniel gripped his chair until his knuckles blanched.

Twelve white jurors—livelihood dependent on the system—found Elias guilty of insurrectionary behavior and moral turpitude; Clara mentally unfit and dangerously influenced.

Leniency for Clara—a cage called home.

Example made of Elias—a lifetime in the quarry.

“Mercy,” Nathaniel called it.

“Cowardice,” Clara said.

The town moved on.

Clara’s world shrank to rooms under watch—letters burned—iron ring tucked into a dress hem.

Nathaniel drank and judged harder; his daughter’s words carved at his sleep: You were never just.

You were only careful.

Elias carried memory to the quarry: cases recited like Psalms, letters taught on scraps, names held in his head—Whitfield’s signature remembered as a blade.

He told their story in sweat and dust.

Among men, it grew.

Years later, in a rebuilt courthouse, a clerk filed old records.

He found the trial.

Nathaniel’s shaky hand at the verdict.

No mention of Moses’s cabin or iron ring or a daughter calling the law wicked.

Only a narrative fit for order: a colored man corrupting a white woman; the court restoring peace.

The clerk penciled a small question mark in the margin—tiny rebellion, almost invisible.

Stories survive statutes.

Some say Clara died in the house—old and alone—iron ring sewn in her hem.

Some say she left one night while her father slept—walking north with a satchel and memory.

Some say Elias did not survive the quarry; others whisper he did, telling anyone willing to listen that a judge’s daughter once called him husband before an entire town.

What is certain: once, in 1851, in a town that believed itself orderly and righteous, a judge’s daughter and her father’s favorite slave stood in a courtroom and dared to say the law was wrong—that love was not filth—that men were not property because someone wrote it so.

The law did what it always does when challenged: it crushed what it could, erased what it couldn’t.

But stories live longer than statutes.

This one found you.

If you’ve walked that gallery and those yards in your mind, you carry a piece of what kept their defiance alive.

News

The Plantation Lady Replaced Her Husband’s Heir With the Cook’s Slave Child—Georgia’s Silent Scandal

They say the storm that broke over Merryweather Plantation in the spring of 1854 was the worst anyone in that…

The Mistress Who Promised Freedom To The Slave Who Impregnated Her First—She Lied Twice

The first time I saw Helena Ward’s handwriting, it was bleeding through a ledger that should have held nothing more…

The 18-Year-Old Slave Boy Who Impregnated the Governor’s Wife — Virginia 1843

On the night Virginia decided what kind of child it would let a governor’s wife carry, I was still just…

The 7’4 Slave Giant Who Broke 11 Overseers’ Spines Before Turning 22

They say it was the sound that damned him. Not the height—though he stood a full head above any man…

🔥 “They Wrote About Something That Shouldn’t Have Existed Yet…”: Newly Unearthed Sumerian Records Shock the World With Alleged Descriptions of Technology, Sky-Beings, and Events Thousands of Years Ahead of Their Time—A Revelation So Disruptive It Threatens to Rewrite Humanity’s Origin Story and Challenge Every Assumption We Thought Was Untouchable 😱

From the moment archaeologists pried the first cuneiform tablets out of the dust of southern Iraq in the late 1800s,…

🔥 “The Numbers Didn’t Make Sense… Then They Got Worse”: In a Fictionalized Cosmic Exposé, Avi Loeb Reveals He Found Something Terrifying in 3I/ATLAS’s Jet Measurements—Anomalies So Violent, Precise, and Unnatural That NASA’s Silence Only Deepens the Suspicion That This Object Is Not Behaving Like a Comet but Like a Machine Awakening in the Dark 😱

As scientists continue to scrutinize the interstellar object 3I/ATLAS, a growing body of data is revealing patterns that defy conventional…

End of content

No more pages to load