The summer heat in Franklin County, Georgia, did not simply sit on a man; it pushed.

It pressed against lungs and skin, turned tempers brittle, and made cruel ideas sound like common sense.

By July of 1847, the fields along the Savannah River shimmered, the red clay baked to dust, tobacco leaves drooping like tired hands.

It was heat built for mistakes, and Thomas Merik was about to make one that would outlive him.

Clearwater Ridge was his—three thousand acres of bottomland stitched with cotton and tobacco and the slow indentation of feet that did not belong to him.

He was fifty-two, “fair” by the measure of men who spoke that word with a straight face, which meant he fed the people he owned enough to work and put the whip away when it did not profit him.

His wife had been dead five years.

His daughter, Abigail, had grown into a beauty that made mens’ heads turn and their mothers whisper.

Green eyes, dark hair, and the kind of mind planters called dangerous when it lived in a woman.

She read what she pleased, asked questions that wouldn’t sit down, and refused to treat marriage like a purchase of her future by a man she did not respect.

Among the two hundred enslaved people at Clearwater Ridge was a man who moved differently through the world.

He answered to Isaiah now—his birth name having been whipped and bartered away years before—and he was thirty-one, lean strong, the kind of strength built one heavy day at a time.

His hands were calloused thick and his back carried the history of another man’s temper.

The overseers could not stand him, because he was good at what they pretended to understand.

In his head, numbers moved like water.

He could look at a field and tell you what it needed without touching the dirt.

He had taught himself to read from scraps and discards, and he wore his intelligence like a coat you turned inside out in bad weather, showing only what kept you alive.

Thomas noticed anyway.

A man who mined his land for money learned to recognize where value lay, even if it came wrapped in skin the law said was not his equal.

On July 5, the day after white county men toasted their independence—heavy irony standing up around them and clearing its throat—Thomas filled his big house with neighbors and whiskey.

The Witfields came, and the Carsons, and Judge Thaddeus Cole with his wife and boys.

The men did what men do in rooms where nothing checks them: they boasted.

Crop yields grew as they spoke them, prices got better in the telling, and a judge’s boy laughed about a Charleston auction where a “fine buck” fetched eighteen hundred dollars.

Thomas, who had been drinking enough to confuse pride with truth, mentioned Isaiah.

He spoke of him in the way owners do when they want to be admired for noticing the humanity they deny: capable of complex calculations, adept with soil and schedules, quick to learn anything you put near him.

It sounded to the room like bragging boys at a fence.

Jonathan Whitfield barked a laugh.

“If your man is so remarkable, put it to a true test,” he said.

“Something impossible.”

William Cole—the judge’s eldest, twenty-three and cruel for sport—grinned and put down a dare he thought was a joke.

“Have him plant a hundred thousand cornstalks in two months.” He let the room sit with the foolishness.

It was past planting season.

The heat made even breathing work.

No single man could do it above ground and finish before September.

“If he does it,” William added, eyes bright, “give him his freedom.”

It would have been ugly enough if the conversation had stopped there.

Men could have laughed, clapped each other on shoulders for having made good jokes, and gone home to tell their wives how clever they were.

But Thomas, drunk on pride, did not offer Isaiah’s freedom.

He did something worse.

He said, in a voice thickened by whiskey and status, “If Isaiah plants a hundred thousand cornstalks in two months, I will give him my daughter’s hand.”

Silence cracked through the room like lightning.

Then the nervous laughter—high, brittle—of men who wanted to pretend it could only be a joke.

A slave marrying a white woman, the owner’s own daughter.

It was illegal, obscene by their creed, and useful in exactly one way: it made clear that no one expected the condition to be met.

By the next afternoon, William Cole was in Thomas’s tobacco barn, delivering that joke like a summons.

He found Isaiah at work and bled his superiority into the air.

“Your master has bet the world on you,” he said, smiling like the sun at noon.

“One hundred thousand stalks.

Two months.

Miss Abigail as your prize.” He paused to enjoy the contradiction of it.

“It is impossible.

Everyone knows that.

But we shall see if you have the mettle to try.”

Isaiah did not look up until he had put his tools in order.

In the silent beat between William’s words and his own, he counted the angles.

If he refused, he made Thomas small in front of his rivals and paid for it with his own back.

If he tried and failed, he proved everything they said about the limits of a body like his.

If he tried and succeeded—if?—he would force a man who prided himself on honor to choose between law and his word.

Property has no leverage, he thought, except the leverage that comes from making your owner choose in public.

He said, “I will do it.”

When the message came back to Thomas that the man he owned had accepted the terms a sober fear climbed into his throat.

What had been a stupid sentence became a path he could not see the end of.

He hauled Isaiah into his study that night, sat him in front of ledgers and decanters, and called him a fool.

“You cannot possibly succeed,” he said.

“It is designed to make you fail.”

“I understand, Master Thomas,” Isaiah said, eyes steady.

“Then why accept?”

“Because you promised your daughter if I did.”

“This cannot be honored,” Thomas hissed.

“It is illegal.

You would be killed.

I would be ruined.

It is a farce—”

“It was your word,” Isaiah said softly, the most dangerous thing a man could say to a man built on the idea that his word made him.

“You spoke it where they could hear you.

If I succeed and you break it, you are the liar they will talk about when your back is turned.”

Thomas waved him away.

Rage would have been easier.

What he felt was respect he did not want and a fear of being made small by a story he could not control.

In the quarters, the wager ran like water under doors.

Men shook their heads and told Isaiah he was crazy.

“You will die for nothing,” Josiah said, twenty years on Clearwater Ridge and slow to believe in miracles.

Isaiah said he might, and meant it.

“It’s the only chance I will ever have,” he said.

“If not to win her, then to force a choice.”

The mathematics were an unsympathetic god.

A hundred thousand stalks in sixty days meant sixteen hundred and sixty-seven every day without fail.

Rain would take days; fever would take more.

Summer would take breath.

He went to Thomas and asked for forty acres of bottomland near the river—fallow for two years.

He asked for seed and was given it, maybe because Thomas was curious, maybe because paying in corn was easier than paying in honor.

He rose at three a.m.

and broke the ground by torchlight.

At sunrise, he shouldered his day’s assigned labor under the overseers’ eyes and returned to his field after dark.

He slept sitting up, hands bleeding through new blisters into old callus.

At the end of the first week, five acres were ready and four thousand seeds were under dirt.

By mid-July, the field showed green at the edges, neat rows beginning to announce themselves.

He was ahead of his schedule by inches and already half of himself.

Abigail found out properly in a whisper from Clara, the housemaid whose patience for white foolishness had limits.

“Your father staked you like a horse,” Clara said, with the clarity of someone not allowed to pretend ugliness is anything else.

Abigail walked into her father’s study with her head up.

“You wagered me,” she said.

He called it a drunken joke.

He said the promise was impossible to honor.

“Then you should not have made it,” she replied.

“You should go and see what your words have made.”

At dawn the next day she rode down to the river.

Isaiah did not see her at first, so she watched him as he found a rhythm that kept him moving.

Dig, drop, cover.

Every three motions looked like the last.

He looked up only when she said his name.

He took his hat off.

“Miss Abigail.”

“My father says this is impossible,” she said.

“It seems so,” he answered.

“But I am trying.”

“Why?” It came out like a real question, not a test.

“Because it is the only chance I will ever have to make him choose,” Isaiah said, and the honesty of it arrested her.

“You are the symbol.

Freedom is the thing.

If I succeed, the story will be told whether he keeps his word or not.”

By the end of July, thirty thousand stalks threw small shadows over the river bottom.

Isaiah still could not afford to stop.

A week later, a thunderstorm tore a section of new plantings and carried three thousand hopes downriver in a brown rush.

He replanted with that grim calm his work had given him, fighting time like an enemy who never tired.

Other slaves began to help when they could.

They were not allowed to choose much in their own lives; they could choose this.

They loosened soil along the edges of their assigned fields when overseers turned their horses.

They dropped seeds, covered sprouts with straw, fetched him water passed hand to hand when the heat pushed men to the ground.

In early August, men who had laughed began riding down to count.

William Cole came every week, pretending fairness and hoping for failure.

They sampled rows, extrapolated from squares, did the arithmetic out loud as if sound made truth more true.

The idea stopped being a joke and started being an argument with the world as they believed it was.

On the twentieth, Thomas sent for Isaiah and tried to buy his way out.

“I will manumit you now,” he said, sliding papers across oak.

“Five thousand in gold.

Letters to Philadelphia.

Freedom, without this folly that will kill you.”

“Your way still has you in charge of what I deserve,” Isaiah answered.

“I will finish or fall trying.

Then you will show yourself to be either a man who keeps his word or a man who does not.”

By the first of September, ninety degrees was considered a cool day.

Isaiah had planted eighty-five thousand stalks and had not slept properly in weeks.

He shook with fever that wrung him like a rag.

On the third, Abigail found him working with the clumsy insistence of a drunk.

He would plant three seeds and stare at the hole like he had never seen one before.

“Stop,” she said, in a voice that would have stopped other men.

He did not.

She caught his arm.

He was hot to the touch.

“You will die to make a point that cannot change this world.”

“It can change mine,” he said, words slurring.

“It can force him to choose.

I promised Sarah,” he added suddenly, the name falling out of him like a stone.

“Who is Sarah?”

“My wife,” he said.

“Was.

They sold her and our girl to Mississippi.

They died there under a man who didn’t care if a field was harvested with blood.

I tried…to save…enough.

You cannot fight price with hope.” He pressed his hand to his chest.

“I promised I would be free.

I promised I would make the men who did this decide who they are out loud.”

That night, Abigail took three torches and Clara and two house slaves with good backs and brave hearts.

They went to the field and planted until dawn chased them home.

On the fifth—the last night left—Abigail sent notes by hands that knew which doors to knock on in the dark.

Twenty enslaved people from five neighboring plantations slipped out and into Clearwater’s bottomland like old ghosts.

In near perfect silence they put five thousand more seeds under earth.

They left before dawn without looking back at what they had made.

At noon on September 6, landowners in cravats stood in a field of corn that had no business existing.

They counted plots, argued about formulas, agreed and then disagreed, and came, finally, to the same number: one hundred thousand and change.

William said the man had cheated—he must have—because the alternative was admitting that the world needed a new set of rules.

Judge Cole, eyes narrowed, reminded him the wager had said nothing about doing it entirely alone.

The men looked at each other over their own pride and saw a world that would not mind being changed without asking permission.

That evening, the big house filled with witnesses and the wives who would report how they had held themselves while the world creaked.

Thomas stood straight, like a man who could not afford to lean.

“Isaiah has done what I required,” he said.

“But my promise cannot be legally fulfilled.

The law forbids such marriages.

To honor it openly would destroy us.

I offer instead your freedom, five thousand in gold, and letters north.”

“It is not what you promised,” Isaiah said, voice wrecked and steady.

“Keep your word, or say out loud that you are a liar where the men who care about such things can hear you.”

Every man in the room felt the edges of that blade.

Honor woven into law—what happens when they scrape against each other? Judge Cole surprised himself by offering a third way: a private ceremony, witnessed but not recorded, then a carriage pointed north.

“The spirit of the promise,” he said, as if spirits mattered more than ledgers.

They looked to Abigail.

She had watched the men talk like ships signaling each other across fog.

“I agree,” she said.

“I will marry him tonight and leave at dawn.”

Thomas saw then that he had lost two things at once—his property and his daughter—and that both had turned into their own kinds of fire.

He nodded because he could not do anything else without blowing up what remained of the story he had built his life around.

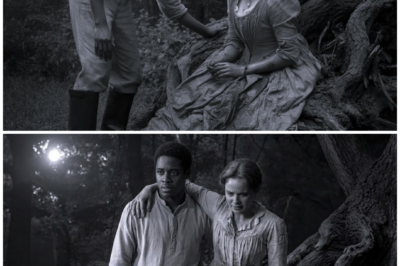

At midnight, in the library where Thomas had made and kept the accounts that counted, Abigail and Isaiah stood before Judge Cole and said words that would not keep either of them safe.

Isaiah’s “I do” was a thread pulled out of a last breath; Abigail’s was a stone placed on a grave to say that someone would remember.

They left before sunrise with manumission papers backdated to sleep under their other trouble, five thousand in a wooden box, and letters folded in wax that said the men up north ought to take their calls.

Thomas did not speak to them when they left.

There are silences that keep men standing, and this was one.

Three years later, he died with neighbors still saying his name with their mouths twisted: the man who promised his daughter and did not keep his word; the man whose daughter chose a different thing than he had planned.

In Philadelphia, Isaiah was sick for two weeks and then was not.

He never again breathed easily.

He never again wrote for long without his hand shaking.

He worked anyway.

He did sums for a freedmen’s aid society, taught numbers to boys who had known only how many lashes they had gotten and how many rows remained, made money enough to pay rent on rooms where he could lock the door from the inside.

Abigail wrote; her anger grew teeth and ink.

She told their story in newspapers that wanted to hear it in a northern city that didn’t know what to do with a white woman and a black man who walked down the same sidewalk side by side.

They did not have children—the body keeps an accounting that does not care about desire—but they had a purpose and a house with two chairs.

Isaiah died in 1854 of a body that had been asked to do too much.

Abigail lived thirty years more, long enough to watch a war and a proclamation and to bury men who had once laughed in dining rooms.

The corn in Clearwater’s bottomland came up stronger than any Thomas had seen in a year that dry.

He set it on fire rather than profit from what had made him small.

The bottomland went to brush and slept under vines men ignored when they rode past with stories in their mouths.

Years later, the teller changes a detail here and there.

In some, Isaiah is a saint who never broke, an impulse to make the hard thing his heart did look easy.

In some, Abigail is a martyr whose noble choice cost her nothing but comfort.

The truth is more spare and more useful.

An enslaved man did arithmetic too large for his body and kept doing it until he could not.

A plantation daughter decided her father’s honor bound her more tightly than his law.

A room full of men were forced to pick between their word and the rules they had written and enforced for everyone else.

The choice could not change the whole world at once.

It changed the shape of a few lives and cracked the certainty of a few others.

That is how doors begin to appear in walls.

In slave quarters after dark, the story became a whisper mothers told their sons when they wanted to teach them what backbone sounds like.

A man planted a hundred thousand seeds in two months to force a man to look at himself in public.

A woman said yes to a spectacle of honor so that a promise could be something other than air.

Nobody had to believe at the start.

Belief did not plant a single seed.

Will did.

And the stubborn refusal to treat “impossible” as the only answer a person is allowed to believe in.

Men like Thomas built a world on the idea that everything important could be counted and bought.

In July of 1847, in a field along a river where the air pressed down like a hand, a man they counted as property built a proof they could not fold back into their ledgers.

He planted impossible numbers into dirt and stood in front of men who did not know which of their own rules they were supposed to keep.

That kind of uncertainty is its own kind of revolution.

And once it starts, it has a way of growing.

News

Slave Finds the Master’s Wife Injured in the Woods — What Happened Next Changed Everything

The scream was so faint it could have been a fox, or a branch torn by wind. Solomon froze on…

The Slave Woman With a Burned Face Who Haunted Slave Catchers Across Three States

They called her a ghost because it was easier than admitting they were afraid of a woman. The slave woman…

Master’s Son Noticed How His Mother Looked at the Slave Boy — One Night, He Followed Her

The plantation lay across the land like an old wound: rows of cotton stitched into the earth, a white house…

A Slave Boy Sees the Master’s Wife Crying in the Kitchen — She Reveals a Secret No One Knew

Samuel learned to live without sound. At twelve, he could pass from pantry to parlor like a draft—present enough to…

Young Slave Is Ordered to Clean the Master’s Bedroom — He Finds the Wife Waiting Alone

Thomas had learned to live as a shadow. At nineteen, he could move from dawn to dusk without drawing a…

(1855, AL) The Judge’s Widow Ordered Two Slaves to Serve Her at Night—One Became Her Secret Master

The townspeople of Fair Hope said the Ashdown house never quite went dark after the judge died. On still nights…

End of content

No more pages to load