The 7’6 Giant Who Made His Masters Flee: Cartagena’s Most Disturbing Story (1782)

On the night of August 15, 1782, something ancient stirred in the shadows of a Spanish Caribbean estate.

The screams from Hacienda San Rafael didn’t sound human.

They sounded like chains breaking after centuries.

They sounded like a giant taking his revenge.

At sunrise over Cartagena de Indias, eleven bodies lay scattered across the property.

But the most terrifying detail wasn’t the death toll.

It was the discovery that the 7’6 slave—known only as the Monster—had vanished into the jungle and taken with him the teenage daughter of the man who had enslaved him.

This is the real story Colombia tried to erase from its archives for two centuries—a story of vengeance, betrayal, and an impossible love that defied the laws of God and men.

Cartagena de Indias, May 1780—midday heat turned the cobblestone streets into stone ovens.

The air smelled of salt mixed with something darker, something that clung to the throat like rancid oil.

It was the smell of concentrated human suffering.

Cartagena wasn’t just the heart of Spain’s Caribbean trade; it was the most lucrative market of human flesh in the New World.

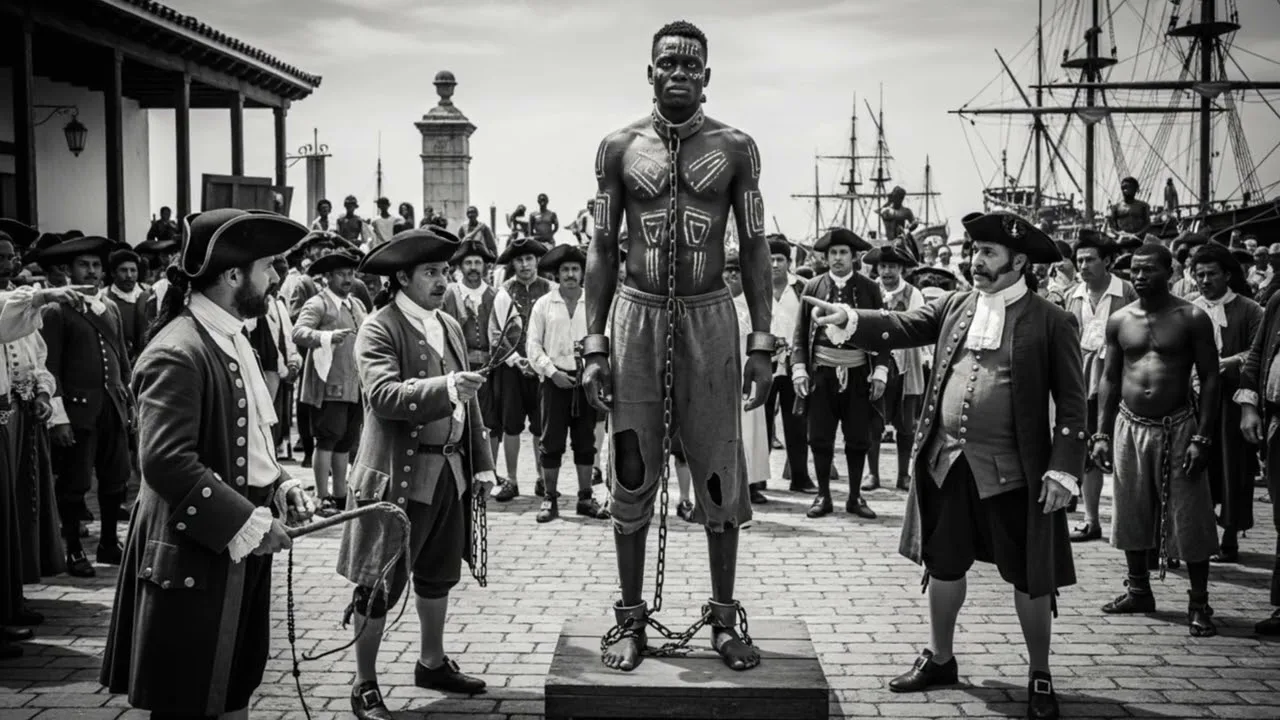

Slave ships docked weekly, unloading souls from West Africa—men, women, and children chained, branded, and sold like livestock to the wealthiest planters of New Granada.

At the Pegasos pier, where enslaved Africans were exhibited before auction, men in silk coats and broad-brimmed hats fanned themselves and inspected mouths as if examining horses.

Women were pawed without shame, men forced to flex their muscles to show value.

That May day, something stopped the market’s hum.

A murmur swept the crowd like electricity, then astonished shouts, then a silence so heavy even street vendors fell quiet.

From the belly of a Portuguese slaver named Santa Teresa de Ávila emerged a figure that defied understanding.

First, the hands—hands large enough to crush a skull like an orange.

Then the shoulders—wide as two men side-by-side.

And finally, standing fully upright, the crowd instinctively stepped back: seven feet six inches of contained fury.

His skin was polished obsidian sweating captivity; his bare torso bore ritual scars in geometric patterns—tribal marks from the Gold Coast, present-day Ghana.

His face was carved in stone—wide cheekbones, square jaw, eyes that looked through people toward something deeper and terrible.

The Portuguese traders had given him a name: O Monstro.

The Monster.

Two thick iron chains circled his neck.

Shackles at wrists and ankles were linked to a wooden bar that prevented him from closing his arms.

Even so, he walked down the gangplank with a dignity that made some spectators cross themselves.

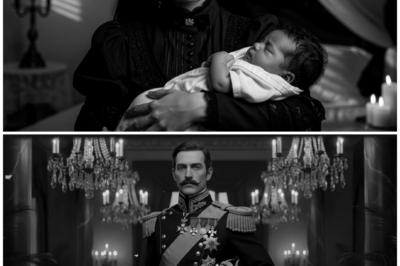

Don Sebastián Montoya y Bracamonte watched from a colonnade’s shade.

Fifty-two, gray hair slicked with coconut oil, neatly trimmed mustache; blue coat with silver buttons, white linen trousers, Spanish leather boots to the knee.

Ebony rosary in his right hand.

Coiled whip in his left.

Owner of Hacienda San Rafael—800 hectares of sugar cane and indigo outside Cartagena—he owned one hundred forty people.

Not elite among elites; viceroys and major merchants regarded him with condescension.

But in Cartagena his name opened doors.

His cruelty closed mouths.

He saw the giant and his eyes lit with that particular gleam men have when they see a chance to prove power.

He walked to the Portuguese broker, a small, nervous man named Da Silva sweating under a straw hat.

“How much for the giant?”

Da Silva dabbed his forehead with a stained handkerchief.

“Don Sebastián, with respect—this is no ordinary slave.

He has gigantism.

A curse of God.

We had to chain him double; he broke normal rings.

Three sailors tried to subdue him on the voyage.

One lost four teeth, another’s arm remains broken.”

“I don’t care about his biography,” Don Sebastián said.

“I want a price.”

“1,200 pesos gold.”

Gasps.

The average price for a healthy adult was around 300 pesos.

“Eight hundred,” Don Sebastián said.

“Don Sebastián—this man is a spectacle.

Imagine him in your fields.

The others will see and know resistance is futile.

Pure intimidation.”

“Nine hundred,” he said.

“Final offer before I find a seller less greedy.”

Da Silva looked at the giant, then back.

He nodded, knowing no other buyer would pay half.

“Deal.

But I warn you—he hasn’t spoken a single word since we captured him eight months ago on the Gold Coast.

Neither on the ship nor under softening tortures.

We don’t know if he understands Spanish or Portuguese.

And there’s something in his eyes that makes even the hardest men avoid looking directly.”

Don Sebastián stepped to the giant for the first time.

He had to tilt his head back to see his full face.

For one brief second, he felt something he hadn’t since childhood: fear.

But Montoya had built his fortune breaking rebellious slaves one by one.

This giant would be no different.

He unfurled the whip and cracked it in the air.

“Kneel,” he ordered in Spanish.

The giant didn’t move.

“I said, kneel, beast.”

Nothing.

Don Sebastián stepped forward and struck the giant’s chest.

The leather bit skin, opening a bleeding welt.

The crowd held its breath.

The giant didn’t blink.

He slowly, very slowly, tipped his head toward Don Sebastián.

Then something happened that made the broker’s spine go cold.

The giant smiled.

Not a smile of submission or fear.

The smile of a predator who knows exactly when he will attack.

He was just waiting for the perfect moment.

That night, the giant rode in a reinforced cart to Hacienda San Rafael—four hours on muddy roads winding through plantains and slave villages of the recently freed.

Don Sebastián rode ahead on a black Andalusian gelding, flanked by two overseers with muskets.

In back, the cart carried the chained giant, sitting, watching the landscape with a focus that made drivers uneasy.

By the time they arrived, the full moon shone over cane fields.

San Rafael’s great house—white, two stories, red-tiled roof—stood among slave barracks, stables, a sugar mill powered by a massive waterwheel, and miles of plantations losing themselves to jungle.

Night laborers paused to see the newcomer.

Even at a distance, his size could not be ignored.

An elderly slave named Yemayá—born in Dahomey, considered a healer—crossed herself.

“Ogun has arrived,” she whispered in Yoruba.

“The god of war comes to collect blood.”

Don Sebastián ordered the giant taken to the men’s barracks—a long wooden building with palm-thatch roof, divided into compartments for up to eight slaves.

The head overseer, a cruel mulatto named Domingo, shook his head.

“He won’t fit in normal barracks.

And we cannot mix him with others.

If he organizes a revolt at that size—lock him in the tool shed for now.

Tomorrow we decide.”

The shed—ten feet by ten feet with no windows—stored hoes, machetes, and spare chains.

They shoved the giant inside, locked the door, and posted two armed guards.

Don Sebastián returned to the house where his wife, Doña Constanza, and his daughter, Inés, waited with dinner.

Doña Constanza—forty-five, sharp face, hair in a severe bun—had worn black ever since burying two sons to yellow fever ten years earlier.

She spoke little and smiled less.

Her only pleasure seemed to be praying the rosary five times a day.

Inés had just turned sixteen—black hair to her waist, green eyes inherited from a Basque grandfather, pale skin that, according to Doña Constanza, must never touch sun.

She was beautiful—and curious.

Curiosity got her in trouble.

Rebellion came in small acts: reading forbidden books from her father’s study, listening at doors, asking questions proper young women should not ask.

At dinner, Don Sebastián talked enthusiastically about his new acquisition.

“A unique specimen.

Tomorrow I’ll put him at the mill.

I want all the slaves to see what happens when you challenge the natural order.”

“What natural order?” Inés asked, pushing her food.

He glared.

“God’s order.

Some are born to command, others to obey.

Blacks are descendants of Ham—cursed by Noah.

It is our duty to civilize them through work.

That man was once free? A savage in Africa.

We brought him here.

Now he can serve the true faith.

Mercy.”

Inés wanted to say more; her mother’s warning look silenced her.

That night, while the estate slept, Inés rose.

From her second-floor window she could see the tool shed.

The guards dozed, muskets across their laps.

She did not know why—but something pulled her there.

She crept down wooden stairs, avoiding the ones that creaked.

She slipped out the back door and crossed wet grass.

The guards snored.

Inés placed her ear to the wooden door.

Silence.

She turned to leave and heard something—not sound exactly, but vibration—a deep, guttural chant in a language she had never heard.

The words were incomprehensible; the emotion behind them was universal.

It was a man mourning something lost forever.

Inés felt sudden tears.

She did not know why she cried for a slave she’d just met.

She only knew that, separated by a door, two prisoners recognized each other—one chained by iron, the other by society’s expectations.

Dawn at San Rafael began at four with an iron bell ringing sentence.

Fifteen minutes to rise, use the communal latrines, swallow rations of maize and salt, sometimes cassava—and line up for assignment.

The morning after the giant arrived, all the slaves gathered in the central yard—even the sick, even the women with babies.

Don Sebastián wanted everyone to see what he had purchased.

When they opened the shed, the giant blinked into dawn.

Chains dragged through red earth.

Slaves stepped back, murmurs rippling.

Don Sebastián stood on the porch like a judge.

“This,” he shouted, “is your new coworker.

Some of you think his size makes him special.

I will be clear: there are no special men here.

Only useful tools—and tools that must be taught.”

He signaled Domingo—the head overseer, tall, muscular, copper-skinned—son of a Spaniard and an enslaved woman, raised on the estate, rewarded for meticulous brutality.

Slaves hated him more than Montoya because Domingo was one of them—and chose the side of the oppressor.

“You,” Domingo said to the giant.

“Do you have a name?”

Silence.

“I asked you a question, monster.

Do you have a name?”

The giant looked at him with a flat, expressionless stare more terrifying than any threat.

Domingo stepped close, whip ready.

“Here you will be whatever we decide.

From today you are Josué—the biblical warrior—because you will work like ten men.” He cracked the whip near the giant’s face.

“Now kneel before your master.”

The giant didn’t move.

Domingo glanced at Don Sebastián—who gave a small nod.

Domingo lay the whip into the giant’s back.

Leather opened a bleeding strip.

He struck again and again.

Ten lashes.

The giant remained standing without a sound.

Slaves watched horrified—some crying silently, others averting eyes from the public humiliation.

Finally, the giant spoke.

His voice was thunder—mixed Portuguese and something older.

“My name is Kwamé.”

Silence fell.

“My name,” he repeated, looking directly at Montoya, “is Kwamé.

Not Josué.

Not Monster.”

Don Sebastián stepped down from the porch and stopped face-to-face, tilting his head back to meet Kwamé’s eyes.

“Very well, Kwamé.

Keep your pagan name.

In this estate, names mean nothing.

Only work counts.

You will work until that stupid pride breaks like dry twig.”

He turned to Domingo.

“Take him to the mill.

I want him doing the work of three men.

No rest until sundown.

No water until quota is met.

Teach him what disobedience means.”

The mill—trapiche—was the estate’s heart.

Cane was processed there—cut in fields under tropical sun, carted to the mill, fed to large wooden rollers turned by a waterwheel.

Rollers chewed cane, extracting sweet juice flowing to giant cauldrons.

Roller work was deadly.

Men pushed fresh cane constantly; one moment of distraction and a hand or entire arm could be caught and crushed.

Every year two or three slaves died that way.

Kwamé was assigned to feed the rollers—normally done by three men in two-hour turns.

Domingo ordered Kwamé to do it alone—from six in the morning until six at night.

Heat gathered in the air.

Kwamé began, taking cane—ten-foot stalks as thick as a man’s forearms—and shoving them toward hungry rollers.

Muscles tensed under sweat-slick skin like ship’s ropes.

One hour.

Two.

Slaves working on cauldrons or hauling cane watched with awe and horror.

No man could keep that pace.

Physically impossible.

Kwamé continued.

Domingo watched from shade, sipping cool water from an earthen jar.

He smiled when he saw Kwamé’s muscles tremble with exhaustion.

“Hold, giant,” he murmured.

“Let’s see how long your pride lasts.”

By noon, with the sun directly overhead, heat shimmering, Kwamé kept working—breath heavy, sweat pouring in rivers, hands bleeding from embedded cane splinters.

Around two, the inevitable happened.

Kwamé stumbled—foot caught on a fallen cane root—balance lost for a fraction of a second—right hand falling toward the rollers.

Slaves shouted warning.

Kwamé reacted with speed defying his size—spun his body, used the fall’s momentum to roll aside.

The palm of his hand grazed a roller—enough to rip skin before he pulled back.

He stayed on the ground, breathing hard, staring at his bleeding hand.

Domingo approached, whip ready.

“Up.

I didn’t give you permission to rest.”

Kwamé lifted his head slowly.

His eyes—until now distant and flat—burned with something alive and dangerous.

“One day,” he said, voice low and clear, “you will pay for every blow.”

Domingo laughed.

“You threaten me, slave? You know what we do to blacks who threaten their betters—”

“It’s not a threat,” Kwamé said.

“It’s a promise.”

Domingo raised the whip to split Kwamé’s face.

A voice stopped him.

“Enough.”

Everyone turned.

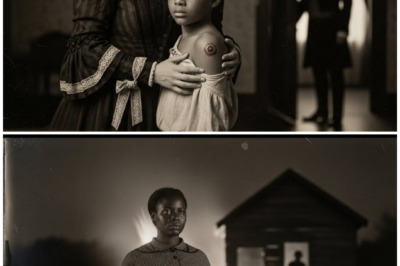

Inés stood in the mill entrance—simple white cotton dress, hair in a braid, cheeks flushed from running under the sun.

Domingo lowered the whip, confused.

“Señorita Inés, you shouldn’t be here.

This is no place for a lady.”

“My father sent me to check that the new slave is working properly,” she lied—surprised at her own calm.

“He is exhausted.

A dead slave is worthless.

Give him water.”

“Don Sebastián ordered—”

“Are you disobeying the Montoya family?” Inés lifted her chin with an authority born of generations.

“Bring water.

Now.”

Domingo clenched his jaw—but obeyed.

He signaled a cauldron worker to fetch a ladle.

Inés took it and walked to Kwamé—still kneeling.

Heads turned.

In a colonial Caribbean world, a decent white girl should not even meet the eyes of a male slave—much less come close enough to touch him.

Inés extended the ladle.

“Drink.”

For the first time, Kwamé truly looked at her.

Their eyes met for a long, impossible moment.

He saw a girl who should be embroidering in a cool salon—not risking reputation for an unknown slave.

She saw a man broken by brutality—refusing to break.

He took the ladle in his wounded hand and drank—cool water sliding down his throat like salvation.

“Thank you, señorita,” he said.

Inés nodded, face neutral for the others.

As she turned to leave, she whispered so only he could hear: “Resist.”

That night, when slaves returned to barracks, Kwamé was finally assigned a corner space—barely six by six feet—with a straw mat and a clay water bowl.

Others watched him with a mix of respect and fear.

No one spoke.

He could feel their looks and whispers.

Nearly all slept when a figure slid from shadows and sat beside him—a fortyish man with dark skin and ritual scars like Kwamé’s—less elaborate—and a dragging left leg healed wrong after a fracture.

“My name is Adebayó,” he whispered in Yoruba.

“I am from the lands of Oyó.”

Kwamé looked at him—surprised to hear African language for the first time since capture.

“Gold Coast,” he said.

“Ashanti kingdom.”

Adebayó nodded.

“You are a warrior.

I see it in your scars—the marks of combat initiates.”

“I was,” Kwamé said.

“No longer.”

“A warrior never stops being one,” Adebayó replied.

“He waits for the right time.”

Kwamé closed his eyes—day’s exhaustion finally hitting.

“There are no battles to win here.

Only survival.”

“You are wrong, brother.” Adebayó leaned closer.

“There has always been resistance.

Spaniards think us broken animals—but there are networks, communication between estates.

We know the names of cimarrones in the San Jacinto mountains.

We know the palenques—fortified maroon villages.”

“And what does that have to do with me?”

“You could be the leader we’ve waited for.

Your size, your strength—others already whisper.

They say you are Ogun in flesh—god of war walking among us.”

“I am no god,” Kwamé said.

“I am a man who lost everything.”

“Then you are perfect,” Adebayó said.

“Men with nothing to lose are the most dangerous.”

Months ground on.

Dawn to dusk, the mill consumed bodies.

Montoya decided the giant was his personal project—a living demonstration that even nature’s wildness could be tamed by Spanish will.

Despite punishing work, lashes, reduced rations—despite everything—Kwamé did not break.

He rose every morning and worked; he returned to his mat nightly without giving his captors a single satisfying sound.

In the shadows, Adebayó met with carefully chosen men and women—those who still hated Montoya with the capacity to act.

They spoke of resistance.

They watched the guards’ schedules.

They learned the house’s layout.

They remembered faces of overseers who would need to be eliminated first.

Meanwhile, another story unfolded upstairs.

Inés could not stop thinking about the giant.

At first, she called it curiosity—how often does one see a man over seven feet tall? She knew it wasn’t true.

It was not his size—it was the unbroken dignity he held even when lashed like an animal.

He reminded her of phrases in forbidden French books—natural rights; human liberty.

Dangerous ideas that could get someone charged with heresy.

One July night, after confirming her parents slept, Inés took a basket—bandages, ointments stolen from her mother’s cabinet, dried meat wrapped in cloth.

Night guards rotated every hour; Inés knew their patterns.

Sixteen years on this estate—she knew every tree, path, and moment of distraction.

She slipped into the men’s barracks through a side door rarely locked.

Inside smelled of sweat, wood smoke, and something indefinable—the odor of concentrated despair.

Men snored softly, others flinched from dreams likely nightmares.

Inés stepped carefully to Kwamé’s corner.

He did not sleep; he sat with his back to the wall, eyes open, watching darkness as if he could see through it to elsewhere.

He turned slowly when Inés approached.

They said nothing at first.

“I brought medicine,” she whispered.

“For your wounds.”

He studied her with eyes that had seen things she could never imagine.

“Why?”

Because—she paused.

“Because what my father does to you is wrong.”

“Everything your father does is wrong,” he said flatly.

“Why are you different?”

Fair question.

Inés had no clean answer.

“I don’t know,” she admitted.

“Maybe because I saw you that first day and saw you were still human—that they hadn’t made you what they want you to be.”

His expression softened a fraction.

“Sit,” he said.

“Here.”

She sat on the dirt floor beside him.

She took ointments and bandages.

“Show me your back.”

He turned slowly.

Even in dim light she saw the lattice of scars—some tribal marks from Africa; others new—whip lines in pink and red that would never fully heal.

With trembling hands, Inés cleaned the newest wounds and applied burn ointment.

Kwamé tensed initially; then relaxed.

“What’s your name?” he asked quietly.

“Your real name?”

“Inés Montoya y Bracamonte.”

He repeated it—testing the sound.

“What does it mean?”

“It’s Christian.

Saint Agnes—a Roman martyr.”

“A martyr,” he said—voice bitter.

“Someone who dies for beliefs.”

“We are all martyrs here,” he added.

Inés worked in silence.

“What does ‘Kwamé’ mean?”

“Born on Saturday,” he said.

“In my village—the day of birth determines your name and your destiny.”

“And the destiny of someone born on Saturday?”

“Warrior.

Protector.

Avenger.”

The last word hung between them like a blade.

She finished bandaging.

She didn’t rise.

Her knees nearly touched his arm.

“Tell me of Africa,” she said.

“My father says it is a land of savages.

I don’t believe him.”

He looked at her a long moment.

For the first time since his capture, he truly spoke—of a village in the Ashanti kingdom, built among green hills of palms and cacao; of his wife, Avena—a healer who knew the language of plants; of the morning Portuguese raiders attacked—houses burned, men who resisted killed, women raped in front of families, then chained.

“Oh God,” Inés whispered.

“Your God was not there,” he said.

“Or if He was, He decided to do nothing.”

He described eight months in a slave hold—hundreds packed in darkness, air so dense breathing felt like drowning; bodies thrown overboard like garbage; the last time he saw Avena—Port of Salvador, Brazil—sold to a coffee planter in the mountains; he dragged himself in chains to touch her face one last time; guards beat him unconscious; when he woke, she was gone.

Inés cried—not with pity.

With the terrible awareness of standing on the wrong side of history.

“I’m sorry,” she whispered.

“Your apology does not bring back the dead.”

“I know.

But—if I could do something—anything—”

“Would you do something for me?” he asked—eyes fixed.

“For a slave your father bought like a horse?”

“Yes,” she said without hesitation.

“Why? What do you gain?”

“Because,” she said slowly, “my whole life I’ve been told how to think, act, whom to marry, what future to have.

They tell me I am free because I am white and Spanish.

I am not free, Kwamé.

I am a prisoner in a gilded cage.

And seeing your spirit—seeing you refuse to break—makes me want to be free too.”

That was the first of many nights.

Inés came two, sometimes three times a week—always with medicine, extra food stolen from the pantry—and most valuable of all: information.

She told him conversations overheard when overseers thought no one was listening; she drew rough maps of the estate and surrounding areas; she explained guard schedules, patrol routes, weaknesses in security.

They spoke about deeper things.

He taught her words in Akan.

He told stories of Ashanti resisting the British for generations—gold used in royal ceremonies—life before Europeans complex and civilized.

Inés read quietly from forbidden books—Rousseau, Voltaire—the first texts on natural rights.

Kwamé absorbed them, ideas resonating with lived injustice.

“This Rousseau,” Inés said one night, “says that man is born free but is everywhere in chains.”

“He is right,” Kwamé said.

“But wrong in one thing.”

“What thing?”

“That the chains are metaphor.

Mine are very real.”

“Breaking them,” she said—“is possible.”

“Speak of escape?”

“I speak of freedom.

Not just for you.

For everyone.”

He looked at her—mix of incredulity and admiration.

“The master’s daughter speaks of freeing slaves.

Do you know what your father would do if he discovered this?”

“Lock me in a convent for life,” she said.

“Or marry me off to cure my dangerous ideas.”

“Then you are a fool to risk it.”

“Maybe,” she said.

“Or maybe I am simply tired of standing on the wrong side.”

Three months after his arrival, the line between them changed.

Inés bandaged a new cut on his arm from an “accident” with a machete—both knew it was not accidental.

Her fingers lingered longer than necessary.

He caught her hand gently.

“You shouldn’t touch me like that.”

“Why not?”

“Because I am a slave.

Because if anyone sees—”

“I don’t care,” Inés said—and realized it was true.

They met eyes in the barrack’s dim light; the world beyond—its rules, hierarchies, prohibitions—faded.

He raised his free hand and touched her face with surprising delicacy for his size.

“You are the first person in two years who has treated me as human,” he said.

“Because you are human,” she answered.

“More human than anyone upstairs.”

They kissed—soft at first, tentative, two people crossing a chasm the colony declared impossible, then deeper—urgent—with the hunger of two prisoners finding something like freedom in each other’s arms.

They knew they had crossed a point of no return.

“This is dangerous,” he whispered.

“Everything worthwhile is.”

Someone had seen them.

From shadows, Adebayó watched—and smiled slowly.

Pieces were falling into place.

Discovery was inevitable.

It came one October afternoon—heat so intense the air felt liquid.

Doña Constanza visited barracks to supervise the annual distribution of cloth.

While inspecting dorms, she found something under Kwamé’s mat—poorly hidden in a crack of dirt floor: a handkerchief embroidered with initials—IMB.

Inés Montoya y Bracamonte.

She had embroidered it herself three years earlier.

That night, when Montoya returned from fields, his wife waited in the study—handkerchief in hand—face white as wax.

“Our daughter,” she said, voice trembling, “is corrupted.”

What followed was swift, brutal.

Guards admitted seeing Inés leave the house after curfew.

They did not interrogate Inés; Montoya chose an education of spectacle.

At dawn, all slaves gathered again.

This time, Inés was forced to attend—flanked by her mother—face a mask of shame and fury.

Kwamé was dragged to the yard—hands tied to a post—knees forced to dirt.

Montoya stood before him holding a branding iron red-hot—the same used on cattle.

“You violated the sanctity of my home,” he said, voice cold.

“You corrupted a pure girl with savage attentions.

For this, you will be marked as the beast you are.”

Inés screamed, tried to run forward—her mother’s grip was iron.

“Father—no—it was my fault.

I went to him, not the other way—”

“Silence,” Montoya said.

“A lady bears no guilt when an animal deceives her.”

“He did not deceive me.

I sought him.”

Doña Constanza slapped her so hard Inés fell.

Montoya pressed the branding iron to Kwamé’s face—just below his left eye.

The sound of burning flesh mingled with the smell of cooking meat.

Slaves watched horror-struck.

Some cried openly.

Kwamé did not scream.

He looked directly at Montoya—eyes burning with fire hotter than any iron.

When Montoya finally pulled the iron away, a cross-shaped brand was permanently carved into the giant’s face.

He wiped his hands on a white handkerchief and turned to the slaves.

“Let this be a lesson,” he said.

“In this estate, I am God—and God punishes those who forget their place.”

He ordered one hundred lashes.

Domingo and three overseers took turns.

The whip fell again, again, again—split Kwamé’s back into a bloody mess.

At lash seventy, Kwamé made a sound—not a scream of pain—something more terrifying—a deep, gut laughter that made even hardened overseers hesitate.

At one hundred, he lifted his head—blood flooding his back, soaking his torn trousers, pooling on dirt—face swollen and branded—eyes terribly clear.

“Never will you be a man,” he said, voice low and precise, echoing Montoya’s earlier words, “only a beast with a whip.”

Montoya paled.

For just a moment, fear crossed his face.

“Lock him in the dungeon,” he snapped.

“No food.

No water.

Three days.

Then I will sell him to the first buyer—whatever loss I take.”

They dragged Kwamé to the small stone dungeon beneath the great house—six feet by six—where rebellious slaves were punished with isolation.

They threw him in and padlocked the iron door.

Inés was locked in her room.

Her mother informed her of arrangements to send her to a convent in Bogotá as soon as travel was possible.

Montoya didn’t know that the public punishment had not broken the slaves—it had unified them.

That night, while the estate slept, Adebayó moved silently through barracks—visited specific people, men and women who had been waiting months for a sign.

“The time has come,” he whispered.

“Ogun has bled for us.

Now we bleed for our freedom.”

It wasn’t all the slaves; it never is.

Of the one hundred forty, only forty were willing to risk everything.

Some had families they refused to endanger; others were too broken to imagine resistance.

Forty was enough—especially when those forty included ironworkers with access to tools, cooks who could drug guards’ food, and young men who had been warriors in Africa.

The plan was simple and brutal.

Over the next three days while Kwamé lay in the dungeon, the conspirators hid weapons—kitchen knives, hammers, iron bars—identified the cruelest overseers and guards to eliminate first—planned escape routes to the San Jacinto mountains, rumored to hold cimarrón refuge communities.

One problem: Domingo was too clever, too vigilant.

He could smell rebellion brewing.

The afternoon of the third day, Domingo summoned Adebayó.

He sharpened a long machete slowly.

“I’ve been watching you,” he said.

“You move too much.

You speak to too many.

What are you planning?”

“Nothing, mayoral,” Adebayó said softly.

“Visiting the sick—you know I am a healer.”

“Yes,” Domingo said.

“A healer suddenly very interested in the giant rebel.”

“I pity him,” Adebayó said.

“The master was too cruel.”

“The master was too soft,” Domingo murmured.

“I would have killed that monster on day one.”

He stepped closer—machete in hand.

“If you are planning what I think—by morning, you will be dead.

An accident, of course.

And your friends will have accidents too.”

That night the conspirators met behind the mill.

“Domingo suspects,” Adebayó said.

“If we wait, he will discover everything.”

“We strike tomorrow night,” he said.

“During the storm.”

They looked to the sky.

Black clouds stacked at the horizon.

Tropical thunderstorms pounded the coast weekly this time of year—winds howled like wounded beasts—rain turned earth to slick mud.

“Storms are our allies,” Adebayó said.

“Guards will stay under cover.

Rain will hide our movement.

The spirits are with us.”

He pulled a small bundle from his shirt—dried herbs, a carved wooden figure, red powder glittering in torchlight—a symbol of Shango—Yoruba orixá of thunder and justice.

“The ancestors have waited too long,” he said.

“Tomorrow we collect the blood debt.”

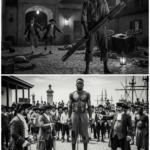

August 15, 1782—the storm struck after dusk exactly as predicted.

Sky turned black-purple.

Wind howled through jungle trees.

First drop fell—then a second—then deluge.

In the great house, Montoya and family ate as thunder cracked.

Doña Constanza crossed herself.

“These storms make me nervous.”

“It’s weather,” Montoya said.

“God demonstrating His power.”

Inés—silent for three days—sat hollow-eyed.

She refused most meals.

She burned—fury neither parent recognized.

In the dungeon below, Kwamé sat in absolute darkness—chains on wrists and ankles bolted to stone.

Three days without food or water should have put him in delirium.

His mind had never been clearer.

He heard the storm above.

He heard guards’ boots running for cover.

He heard something else—the sound that made his heart pound—the sound of a key turning in his cell lock.

The door opened.

A small figure entered with a torch—shadows dancing on wet walls.

It was Inés.

She had stolen keys from her father’s study at dinner—waited until the storm hid all sound.

“I came to free you,” she said without preamble.

He looked through gloom—voice hoarse from thirst.

“Your father will kill you.”

“I don’t care,” she said.

“I can’t—can’t keep being part of this.”

She knelt and worked at shackles with keys—hands shaking, determined.

“There is a plan,” she whispered.

“Adebayó is organizing.

Tonight—tonight everything changes.”

“What plan?”

“Freedom.

Vengeance.

Justice—call it what you want.”

Shackles clanged off.

Kwamé stood slowly—joints cracking after three days chained.

Even weakened, his presence filled the space.

“If I do this,” he said, “if I help—you know there is no going back.”

She met his eyes.

“Good,” she said.

“I don’t want to go back.”

Up in the barracks, Adebayó gave the signal.

Forty conspirators moved at once.

They slipped from dorms—carried hidden weapons—made for assigned targets.

Zara, the cook, entered Domingo’s private hut.

She had drugged his dinner with belladonna—enough to make him sleep deeply—but not enough to kill.

Yet.

She shook him softly.

“Mayoral—the mill—there’s a problem.

Don Sebastián wants you.”

Domingo—half under drug—grunted, rose, and stumbled into storm.

He never reached the mill.

Six men waited in darkness between barracks—grabbed him before he could shout.

Kofi, a young man Domingo had whipped in the eye the year before, whispered in his ear: “Now you will see how it feels.”

They took their time.

They used the techniques Domingo had used on them.

Every scar they had received—returned with interest.

When they finished, Domingo was unrecognizable.

Other groups moved.

Two front gate guards fell to hammer blows before reaching muskets.

Overseers in huts near fields were visited one by one.

Some died quickly.

Others did not.

The great house’s front door burst open.

Wind and rain flooded in—and with them the rebels.

Montoya fired both dueling pistols.

One bullet hit a young man—killed him instantly.

The other missed.

Hands grabbed Montoya—dragged him to the marble hall.

Threw him to the floor.

He looked up and saw what made his bladder release.

Kwamé stood at the entrance—drenched—brand on his face glowing red in torchlight.

Adebayó stood beside him.

Behind them, forty slaves with eyes burning decades of rage.

“Please,” Montoya whispered.

“I have money.

I can pay.”

“You paid,” Kwamé said—voice like thunder.

“You paid when you bought your first slave, when you gave your first lash, when you marked my face.

Now I collect your debt.”

“I am a man of God,” Montoya stammered.

“You cannot—”

“Your God is not here,” Kwamé said.

“Only the orixás—and they demand justice.”

Adebayó took rope—the rope Montoya used to hang rebellious slaves publicly.

“All men are equal in death,” he said.

“Let’s see if you bleed like us.”

What happened next cannot be written in full.

Some acts of vengeance defy description.

Enough to say: when the storm ended, eleven bodies lay across the estate.

Montoya was found in his study—strangled with his ebony rosary.

Doña Constanza—found drowned in her wash basin.

Overseers and guards hung from the same beams where they had hung rebellious slaves.

One body was missing.

Inés Montoya y Bracamonte had disappeared.

August 16—smoke rose from burned outbuildings—the mill, overseers’ barracks—part of the great house.

The first to see the massacre were workers from a neighboring estate—who ran back to Cartagena with stories increasing in horror with each retelling.

By noon, the provincial governor—Don Alfonso Herrera y Sotomayor—had the news.

By afternoon, riders carried urgent reports to Bogotá—slave insurrection.

The response was swift and brutal.

Governor Herrera—sixty, with military experience against Mapuche in Chile—understood that a successful slave rebellion was gunpowder.

If not snuffed immediately, it would spread estate to estate until the coast burned in revolt.

He assembled sixty regular soldiers from Cartagena’s infantry tercio—muskets, pistols, sabers—and added twenty cimarrón trackers—free mulatto and black men who made a living hunting escaped slaves through jungle.

The most famous of these hunters was known only as El Sabueso—the Bloodhound—a mulatto with a lost eye covered by black leather patch.

They said he could follow a two-week-old trail—that he understood the jungle better than cimarrones—and that he had never failed to bring back a fugitive—alive or dead.

The expedition left Cartagena August 18—three days after the massacre—with two weeks’ provisions, enough ammunition for a small army, and explicit orders: capture leaders alive for public trial and execution; execute followers on the spot; if any white woman is with them, rescue her regardless of condition or complicity.

Rumor that Inés fled voluntarily had already spread—some said she had been kidnapped; others whispered she had been corrupted—bewitched—made a willing accomplice.

The initial trail was easy—forty people moving together through jungle left obvious markers—broken branches, footprints in mud, camp ashes.

El Sabueso read them like open pages.

“They head for the San Jacinto mountains,” he told Captain Rodrigo de Ávila—young, commanding the expedition.

“They probably seek the palenque of San Basilio—the largest maroon settlement in the region.”

“How far?”

“Three days on foot for normal men,” he said.

“But they carry wounded—I saw blood on the path.

We’ll catch them in two.”

He underestimated Kwamé.

The giant was not brute force alone—trained Ashanti warrior—guerrilla tactics—ambush—trail hiding.

Through the day he taught basic techniques: walk in single file; last man brushes footprints with a branch; never break branches at chest height—only near the ground where it looks natural; if you must make fire, use it two hours before dawn when smoke blends with fog.

He split the group: elders, small children, severely injured took a different route west; the main group went northeast toward San Jacinto.

“We will leave surprises,” he said.

Inés walked silently among the group—wearing slave clothing now—brown cotton dress, crude shoes, black hair braided without jewelry.

She could have been any mixed-race woman fleeing toward freedom.

Inside—chaos.

She had killed someone.

During the night’s confusion a majoral named García tried to drag her up the stairs to use her as a shield.

Inés grabbed a silver candelabrum and hit his head with all her strength—once—twice—three times—until he stopped moving.

She remembered the skull breaking sound; hot blood on her face; the terrible feeling of power—of finally not being helpless.

Kwamé walked beside her.

They had little privacy to speak—occasionally hands brushed; in those moments, something anchored the chaos—purpose.

The first ambush came the third afternoon.

The Spanish column followed the main trail northeast.

El Sabueso halted.

“Something’s wrong,” he said.

“The trail is too obvious—as if they want us to follow.

There—” He sniffed the air.

“Fresh blood.

A lot.”

A shout from the rear: “Captain! We found something!”

In a small clearing off the path hung a body—a San Rafael guard killed during the rebellion—carried by fugitives—displayed for purpose.

Carved crudely into his chest: a message in Spanish: EVERY OPPRESSOR WILL HANG.

The soldiers murmured nervously.

Captain de Ávila tried confidence.

“Psychological intimidation,” he said.

“Continue.”

Morale staggered.

Two hours later, a narrow defile cut between hills thick with vegetation—rocks began to fall—not boulders—fist-sized stones raining from angles impossible to defend.

Three men injured—one concussed badly when a stone struck his helmet.

When soldiers scrambled uphill to catch attackers, they found nothing—just simple rope tied to trees—triggers releasing loose rocks.

The attackers had been gone for hours.

“They’re ghosts,” a young soldier muttered.

“They’re not ghosts,” El Sabueso growled.

“They’re clever.

But no trick beats persistence.

We will find them.”

Confidence frayed.

Next days brought water supplies poisoned with herbs causing violent diarrhea; trails that seemed obvious ended in treacherous swamps sucking men to their knees; simple traps—ankle-height ropes tripping horses; thorn branches ripping uniforms and skin.

Every two or three days another body hung from trees—messages more elaborate: ANCESTORS CLAIM BLOOD.

THIS LAND REJECTS OPPRESSORS.

OGUN COMES FOR YOU.

Ogun’s name rattled black and mulatto trackers—Yoruba orixá of war and iron—men raised in cultures mixing Catholicism with African beliefs—an invoked Ogun was real curse.

Two trackers deserted the fourth night—vanished with weapons and supplies.

El Sabueso let them go.

“Weak men,” he said.

“Better without them.”

Captain de Ávila saw the situation deteriorate—two weeks pursuing—provisions dwindling—men exhausted and terrified—and no sight of a single rebel alive—like chasing spirits.

Day twelve, they found solid sign—a large cave in the San Jacinto foothills—the main group’s camp—fire ashes still warm—fruit rinds—evidence dozens had been there recently.

El Sabueso studied with his good eye.

“They stood here,” he said.

“Twenty-five went west toward the coast—perhaps to steal a boat.

Fifteen to twenty continued toward San Jacinto.

The giant is with the second—I see his prints—they are unmistakable.”

“How far ahead?”

“Six hours, maybe—now we know where they go—San Basilio is two days—send riders to the garrison—trap them in a vise.”

De Ávila nodded—relieved—sent two best riders.

“We continue direct pursuit,” he said.

They didn’t know Kwamé anticipated this tactic.

That night fugitives camped in a deep cave—fire invisible from outside.

Exhausted—alive.

Of the forty who escaped San Rafael, thirty-two remained in the main group—the rest took the western route.

Inés sat next to Kwamé at the group’s edge—others ate meager cassava and wild fruit.

Some prayed—mixes of Catholic prayers and Yoruba chants evolving into a strange beautiful spiritual symphony.

“They’re gaining,” Inés said in a low voice.

“What do we do when they arrive?”

“They won’t,” Kwamé said.

“Tomorrow we reach San Basilio.

Once inside the palenque, they cannot touch us.”

“Will they accept us?” she asked.

“Palenques have code,” he said.

“Every escaped slave at their gates is brother.

And we bring useful talents—Adebayó is a healer; Kofi works iron; you—”

“Me?” she said.

“What?”

“You read—write—keep records.

You are living proof even oppressors’ children can reject oppression.”

Inés touched his hand.

“What happens to us,” she asked, “once we are safe?”

“There is no safe,” he said.

“They will hunt us for years—until each of us is dead or captured.

But if we live one more day in freedom than in chains—we win.”

Next day they reached San Basilio’s defenses.

The palenque—established nearly a century earlier by escaped slaves—sat in a defensible valley ringed by steep mountains.

Access via narrow trails fortified with palisades, ditches, and watch posts.

Centinels surrounded them—armed with bows, spears, old muskets.

The defense leader—a fiftyish woman with white hair and ritual scars like Kwamé’s—less elaborate—named Oyá—the orixá of winds and storms.

She studied the newcomers with eyes hardened by decades of suffering.

“You seek refuge.”

“Yes, Mother,” Adebayó said—using respectful term.

“We come from San Rafael—rebelled—killed our masters.”

“I have heard,” Oyá said.

“Rumors reached us—say a giant killed eleven Spaniards with his bare hands.”

She looked directly at Kwamé.

“I suppose you are that giant.”

“I am a man who defended himself,” he said.

“No man who kills eleven enslavers is only a man,” she said.

“You are Ogun walking in flesh.”

She turned to the group.

“All are welcome,” she said.

“But be clear—here, no one hides.

All work.

All fight when needed.

And no one brings internal trouble.”

Her gaze stopped on Inés.

“Especially you, white girl,” she said.

“Here there are no señoritas and no slaves—only free.

Do you understand?”

“I do,” Inés said firmly.

“I only want to be free.”

Oyá studied her another moment—nodded.

“Then welcome, sister.”

They entered as the sun went down—first time in months—years for some—they slept without fear of lash or scream.

That night, Kwamé and Inés sat at the settlement’s edge under clear mountain stars.

“We did it,” Inés whispered.

“We really escaped.”

“For now,” he said.

“You are always so pessimistic.”

“I am not pessimistic.

I am realist,” he said.

“Spaniards will not give up—they will send more soldiers—perhaps siege the palenque.”

“Perhaps,” she said—and placed a finger on his lips.

“Then let us enjoy this night—who knows how many more we’ll have.”

They kissed under starlight—two people from impossibly different worlds—finding something like love in the most unlikely place.

In jungle darkness, El Sabueso and Spanish soldiers drew closer—bringing more than weapons—bringing imperial resolve that did not admit defeat.

The giant of Cartagena’s story does not end with heroic battle death.

It doesn’t end simply with capture and public execution.

It ends with something rarer—and in many ways, more powerful.

It ends with freedom.

When Spanish soldiers located San Basilio in October 1782, they discovered something that changed their expedition’s course.

The palenque was not alone.

Three other maroon settlements had sent warriors in support.

Nearly three hundred cimarrones stood—armed—ready to defend.

They had terrain advantage—knew each path and ambush—and were willing to die before returning to chains.

Captain de Ávila assessed with cold military logic—and sent a message to Governor Herrera.

“Impossible to take the palenque without massive losses.

Request negotiation.”

Two weeks later, the reply marked a turning point in Caribbean slave resistance.

Herrera—pragmatic and exhausted after months of futile pursuit—authorized an agreement: fugitives of San Rafael were pardoned officially; they could not return to Cartagena; if they remained in San Basilio and ceased attacks on Spanish estates—no further pursuit.

Privately, Herrera wrote: “It is cheaper to have peaceful cimarrones in remote mountains than wage perpetual war against spirits in the jungle.”

The hunt ended not with blood and glory as Spain expected—but with tacit admission some spirits cannot be broken.

In the years after, San Basilio grew—from roughly one hundred fifty people to nearly four hundred by 1804—new fugitives constantly arrived—drawn by stories of freedom.

They built houses of wood and clay—cultivated cassava, plantain, maize—created a society mixing traditions from dozens of African groups with survival’s practical needs.

Kwamé became central—but not supreme leader.

Palenques worked by consensus—communal assemblies where adults voted on decisions.

He participated; his true role lay elsewhere: instructor of defense.

He trained two generations in guerrilla tactics—ambush—reading terrain—Ashanti discipline mixed with local practice.

Under his instruction, San Basilio became virtually impenetrable.

Adebayó established a healing center—attracting even some poor Spaniards from nearby estates—seeking medicine when European methods failed.

He operated in a special building where herbs dried from rafters—resin incense burned.

And Inés—Inés did what no white woman had ever done in the Spanish Caribbean.

She became a cimarrona officially—at least as far as the Spanish were concerned—Inés Montoya had died in the San Rafael rebellion—her few remaining relatives held a funeral mass—buried her symbolically.

In San Basilio, she lived.

She taught children and adults to read and write—established written records of births, deaths, conflict resolutions—negotiated occasionally with mestizo traders at the mountain base—her perfect Spanish and understanding of colonial mind made transactions smoother.

She married Kwamé in a ceremony combining Catholic, Ashanti, and Yoruba elements—not recognized by church or government—recognized by community.

In 1785, Inés gave birth to their first child—a boy raised in freedom—speaking Spanish, Yoruba, and Akan—learning from his father pride in African heritage and from his mother the idea that all humans deserve dignity.

They named him Osei Genakan—“noble.” They had four children—each raised in a world that shouldn’t exist—where Spanish colonial racial categories meant nothing.

Kwamé lived until 1804—sixty years old—elderly for the time—especially for someone who endured what he endured.

Official cause: malaria.

San Basilio’s elders told a different story: they said he decided it was time.

By Ashanti tradition, a man reaching sixty chooses how to die.

He had completed his mission—punished oppressors—freed people—created new life in free land.

One July morning, he rose before dawn—bathed in the river—dressed in kente cloth he had woven over years—walked into the mountains.

Adebayó found him three days later—sitting beneath a giant ceiba—eyes closed—expression at peace.

Beside him—a message carved into bark: EVERY WARRIOR RESTS.

BUT THE WAR FOR FREEDOM NEVER ENDS.

FIGHT, MY CHILDREN.

ALWAYS FIGHT.

They buried him in a three-day ceremony—Yoruba, Ashanti, Congo songs—every African tradition in San Basilio represented.

They placed his body seated—facing east—toward Africa.

Spanish records marked in 1804 the death of an escaped slave of unknown identity.

Cimarrones knew truth: Ogun had walked among them—and returned to the ancestors.

Inés survived him by twenty-eight years—died in 1832 at sixty-six—remarkable age—by then the Spanish empire was crumbling—the Republic of Colombia had emerged—slavery technically remained—but cracks widened.

Her and Kwamé’s grandchildren were young adults in 1832—some still in San Basilio; others had descended to lowlands—using false Spanish names—mixing with freed and mixed populations.

They were living proof the colony’s racial absolutes had never been as solid as elites pretended.

When Inés died, she was buried beside Kwamé under the same ceiba.

A simple stone marked her grave—rough-carved words: “Inés—who chose freedom over privilege—who loved without limits.

Rest in peace, sister.”

Sister.

Not señorita—nor “wife of a slave”—none of the labels colonial society would have used—only sister.

Official Colombian history rarely mentions Kwamé or the San Rafael rebellion.

In the nineteenth and most of the twentieth centuries, national narrative built itself on ideals of racial democracy and harmonious mestizaje.

Stories of rebellious slaves massacring Spanish masters—even monstrous ones—didn’t fit comfortable narrative.

Evidence exists.

In Seville’s Archivo General de Indias, military reports from 1782 mention an insurrection led by a black of abnormal size; in San Basilio’s archives—now UNESCO heritage—oral records passed through generations describe the giant from Africa who married a white woman.

Recent genetic studies of San Basilio’s population found something fascinating: a small subgroup—descendants of roughly fifteen families—show genetic markers combining West African ancestry—Ashanti region of Ghana—with European ancestry—specifically Basque from northern Spain.

Official explanation calls it typical colonial mestizaje.

San Basilio’s elders offer another: they are direct descendants of Kwamé and Inés.

What this story leaves us are uncomfortable questions.

Was Kwamé’s violence justified? He killed eleven people—some directly involved in his torture—others simply born on the wrong side of history—Doña Constanza never wielded a whip—did she deserve to die for complicit silence? Overseers born enslaved—who chose survival by collaborating—victims or villains?

And the most uncomfortable questions: Was Inés a heroine for rejecting privilege—or a traitor to her class and race? Was her love genuine—an equal love—or a romance built on fantasy of saving the Other?

The relatively “happy” ending—Kwamé living to sixty in freedom—validates, in a way, the violence that made it possible.

There are no easy answers.

Only the raw reality that extreme oppression generates extreme resistance—that when you strip people of dignity, hope, and legal routes to liberation, do not be surprised when they seek freedom by any means necessary.

The giant of Cartagena and the rebels of San Rafael give us a story of vengeance—but also of survival, of impossible choices, of love that defied categories, of an uncomfortable truth: the freedom of some is often built on the blood of others.

The giant’s legacy lives in San Basilio’s mountains—in faces of descendants—in songs still sung about the warrior from Africa who refused to break.

It lives in this question that every generation must answer: How far would you go for freedom? And what would you be willing to become to reach it?

News

The Most Beautiful Slave Who Seduced Seven Wives — and Changed Their Destinies Forever (Cuba, 1831)

In April of 1831, seven wives of sugar planters in Matanzas, Cuba, killed their husbands within the same breathless, bitter…

Master Bought an Obese Slave Girl to His Room, Unaware She Had Planned Her Revenge

Master Thomas Caldwell purchased Eliza on a sweltering June afternoon, his eyes sliding over her large frame as he counted…

The Runaway Slave Woman Who Outsmarted Every Hunter in Georgia, No One Returned

Here’s a complete story in US English, structured with clarity and pacing, and without icons. The Runaway Slave Woman Who…

The Countess Who Gave Birth to a Black Son: The Scandal That Destroyed Cuba’s Most Powerful Family

Here’s a clear, complete short story in US English, shaped from your draft. It keeps the historical spine, the courtroom…

The Slave Who Had 6 Children with the President of the United States — He Loved Her for 38 Years

Here’s a complete, self-contained short story shaped from your draft. I’ve kept the voice intimate and steady, built the plan’s…

The Mistress Hid Her Slave’s Child for 12 Years — Until Her Husband Found the Birthmark

The morning Constance Fairfax realized she loved the child more than her own soul, she understood she would have to…

End of content

No more pages to load