The night my father bargained my life away to the man everyone on our plantation called Goliath, the lamplight caught the brass of my wheelchair and made it shine like a shackle.

It was the first time I understood you can be cherished and traded in the same breath—loved and still offered like currency.

By then I had been rejected thirteen times in five years.

Thirteen dinners, thirteen letters, thirteen versions of the same verdict: not worth the trouble.

I pretended I hadn’t heard the phrase the first time, drifting through the winter air from the back steps, but trouble has a way of making itself understood.

My name is Clara Ashdown.

I was born in 1833 on Ashdown Grove, a tobacco plantation twenty miles east of Hillsborough, where red clay clings to boots and memory with equal insistence.

Two siblings died before I could know them; I grew up as the single surviving child, an only-ness that felt like both blessing and sentence.

At nine, I climbed a horse too quick for my legs and paid for it with my spine.

I remember blue sky, white cloud, the far call of a field hand, the stone marker’s edge against my back, and the terrible evidence of my own scream.

Three days later a Raleigh doctor pinched my feet with a pin.

Nothing.

He asked my parents to step outside, not knowing I was awake.

She will live, he said.

The legs are ruined.

She may stand with help.

She will not walk as society expects.

Children? Perhaps.

Perhaps not.

Most men, Major, will not risk such uncertainties.

I became a question mark instead of a girl.

My father adapted the estate like a campaign: ramps over steps, widened doorways, a ground-floor room turned into mine, a fine wheelchair from Wilmington—walnut frame, iron wheels that sang on polished floorboards.

He loved me, and I will never deny that.

He also did what men of his class do with any damaged asset: he made contingency plans.

While other girls learned the dance cards of the Piedmont, my father placed ledgers in my lap.

He had been a lawyer before inheriting Ashdown Grove.

He taught me to balance accounts, to read yields, to add columns longhand.

If you cannot walk, he said without cruelty, your mind must walk twice as far.

I devoured everything: Roman history, philosophy, Blackstone.

At fifteen I read the sentences that turned women into legal shadows, and felt something harden inside me like cooling iron.

At eighteen, the first proposal—a planter from Johnston County, forty-two, widower, acres spilling past his imagination.

He smiled at my hair and my answers and, later, told my father he required a wife who could stand, move about, handle the marital duties expected.

I learned then how swiftly the world reduces a body to a ledger of imagined private capacities.

Twelve more men said polite versions of no.

Rumors filled the spaces between their departures: barren, nervous, unfit.

And the softer cruelty from women: reconcile yourself to spinsterhood, dear.

My Philadelphia doctor had said there was no medical reason I could not bear children.

My aunt patted my hand.

Men don’t want specifics, they want assurances.

No one can give them that with you.

One winter night I rolled to my father’s study and asked him to stop.

He stood in the firelight, gray deepening at his temples.

It is my duty to secure your future, he said.

My future is here, I said.

Let me run the estate with you.

You’ve said yourself I understand every entry in these books.

And when I’m dead? he asked.

When the law says Ashdown Grove must pass to your nearest male relative because you are a woman? When cousin James decides you are a drain? I had read the statutes.

I had no clever answer.

Leave it to me in your will, I tried.

You’re a lawyer.

Find a way.

I have looked for a way every year since you fell, he said.

North Carolina law does not care how clever I am.

He stared into the flames.

I will not die wondering if you are at a cousin’s mercy.

He found his way two months later, early March 1855.

He sent for me, closed the study door, and held a folded packet like a weapon he loathed but intended to use.

I believe I have found a path to secure you after I am gone.

It is unconventional.

It will be called scandalous or worse.

But I will not leave you to men who do not love you.

He glanced toward the window, toward the faint glow of the smithy.

I intend to give you to Elias.

Elias who? Elias Gray.

The blacksmith.

I laughed once, unkind and frightened.

You intend to give me to a blacksmith? Not just any blacksmith.

He is the strongest man on this property.

He can lift what teams cannot.

He is steady, reliable, responsible in ways I’ve not seen in many free men.

He is the sort of person I want at your side when I am gone.

You’re speaking as if he were a husband.

He is enslaved.

I know the law, he said, voice flinting.

The law has cornered us.

No white man of our class will have you.

No court will let you inherit outright.

If I leave you unwed, cousin James owns your fate.

If I marry you to some pitying widower, he will resent you daily.

I will not choose those.

You will choose this? Tie me to a man with no freedom of his own?

I will give you into the care of a man who can lift you, carry you, defend you, he said, and then I will remove his chains so he may stand beside you in truth.

We will go north.

I will petition for his manumission and take you both to Massachusetts.

They do not bar marriages such as the one you would require.

Such as the one I would require.

Have you asked Elias? Not yet.

I wanted to ask you first.

And if I say no?

Then we pin our hopes on a fourteenth and a fifteenth and die knowing we did not dare the one thing that might actually secure you.

What if he does not want me? What if he is cruel? What if he resents being tied to me?

In ten years, my father said, I have seen Elias take blows meant for others and never return them.

I have seen him free a child from a wagon axle with his bare hands.

I have seen him help the elderly to their feet when no one was watching.

If I thought him capable of cruelty toward you, I would not entertain this thought for a heartbeat.

He is still a stranger, I said.

That can be remedied, my father said.

I have asked that he be brought to the house tomorrow.

Speak with him alone if you wish.

I did not sleep.

The forge rang faintly across the yard.

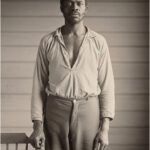

I had seen Elias from a distance, a towering man with arms like ropes and hands that made iron obey.

Children whispered Goliath as if he were both threat and talisman.

And now this: my father’s plan to hand me—white, wealthy, a woman the law calls incompetent—to a man the law calls property, and then unmake the law’s claim on him.

In the morning he filled the doorway like weather.

He ducked beneath the lintel.

His size stole breath, but it was his carefulness that held my attention.

He set his feet as if the floor might be hurt by carelessness.

Miss Clara, my father said, this is Elias Gray.

Then he left us.

You may sit, I said.

He looked at the chair, then at his own body.

I’d rather stand, ma’am.

Do you understand what my father proposes? Yes, ma’am.

When his time is done, I’m to be yours to care for you, see to what you need.

He made it sound like a transfer of ownership, I said dryly.

He almost smiled.

That’s what it is, ain’t it?

It is also my life, I said.

I would like to know whether the man in question has thoughts beyond yes sir.

He raised his eyes fully then.

They were not hard or dull.

They were steady and alive, brown as turned earth, with caution and intelligence and something like weariness.

No one’s ever asked me what I think about who owns me, he said.

So I don’t know how to answer.

Start with this, I said.

Do you want this? Not can you bear it.

Not will you obey.

Do you want it?

He considered, gaze flicking to my chair and back.

I want freedom, he said at last.

That wanting lives in my bones.

Your father says this path might lead there for me—and for you in your way.

If he frees me and I walk away, I have freedom and not much else but these hands.

If I stay as I am, I know that life.

What he’s offering is something I ain’t never seen.

A life I share with someone who knows what it is to be trapped by a body and a law that weren’t their choosing.

You think my chair is the same as your chains? It ain’t the same, he said carefully.

But I’ve seen how the steps stop you, how folks talk over you.

I ain’t blind.

Are you cruel, Elias Gray? No, ma’am.

Do you drink yourself stupid and shout when you don’t get your way? No, ma’am.

Have you ever raised a hand to a woman who could not raise one back? Never.

And I won’t start.

My father thinks you are strength and patience and loyalty.

I need to know there is more to you than a back and a lack of malice.

“There are things I ain’t supposed to say,” he murmured.

Because of the rules about how much a slave is allowed to think? His eyes darted to the door as if the walls could repeat us.

Because of the rules about who gets to sound like they know more than they should.

I read Roman law for amusement, I said.

You will not shock me more than the world already has.

He let out a short, low laugh that surprised us both.

I can read, he said softly.

Learned off a Bible and a boy who didn’t know better than to share.

I read scraps that blow down the road, bits from thrown-out books.

Your father don’t know the half.

What have you read? Whatever words let me slip my skin, he said.

A sermon from a northern preacher.

A pamphlet about a woman speaking on abolition.

There’s an old book of plays in the quarters—pages mildewed, words still there.

Shakespeare, I guessed.

He looked startled.

Yes, ma’am.

I read the one where they argue mercy in a court, but the one I read most is The Tempest.

Caliban, I said.

He nodded.

They call him monster, but he’s the one whose island was stolen.

We talked for an hour—law’s picking winners before any contest begins, freedom like weather that exists in one place and not another, the mechanics of heat and pressure.

The brute I had been taught to see gave way to a man whose mind shaped as surely as his hands.

If you go through with this, I said, people will assume the worst.

They will call me names.

They will call you others.

Are you afraid of that?

I’ve been called animal, tool, boy when I was a man, he said.

Fear from other folks is the air I breathe.

If the price of standing beside someone who sees me as a man is more of the same, then it ain’t as high as what I already pay.

And you? Are you afraid of me?

I am afraid of being helpless, I said.

But I am more afraid of a future where no one who cares whether I live or die has any legal reason to protect me.

If the choice is between being cousin James’s burden or your responsibility, I choose responsibility.

Responsibility? he repeated, throat working.

Yes, ma’am.

Stop calling me ma’am, I said.

At least when we are alone.

If we share a roof, I would prefer my name in your mouth.

He hesitated, then said, low and careful: Clara.

My father returned to find us not quite where he had left us.

I told him I would agree on one condition: We free Elias before we leave.

Not someday.

Before.

I will not be handed from you to another owner.

If I tie my life to his, he cannot be property.

You have my word, my father said.

Before this year is out, Elias Gray will be free.

Bribes, petitions, the narrow doors of law.

North Carolina watched manumission like a suspicious sheriff.

My father framed freedom as reward for extraordinary service: a barn fire, saved lives, loyalty.

He promised Elias would leave the state under white supervision.

He made it sound small enough to be allowed.

A narrow room beside mine was cleared and furnished; at night I listened to his breathing through thin plaster and felt a kind of unexpected safety.

He still worked the forge by day.

By afternoon he learned the landscape of my chair and my body’s limits.

Tell me if anything hurts, he said the first time his arm slid under me.

It all hurts, I snapped, then softened.

Not because of you.

Because I hate needing this.

He adjusted his grip.

We learned each other’s measures.

He wheeled me to the smithy and taught me to move iron.

He put a lighter hammer in my hand and guided me to strike not too hard, not too soft.

My first nail was crooked and ugly.

But you moved it, he said.

Then don’t forget.

Danger came in sideways.

Overseer Kellen’s glare.

Cousin James with his mouth full of filth.

You’re setting your crippled girl up with a negro? Have you gone mad? My father’s voice went steel-cold.

I am securing her protection.

People already talk.

Let them talk about something true.

If he lays a hand on her— Without her consent, my father cut in, I will deal with him as I would any man.

But if you imply my daughter cannot choose who may come near her, I will forget we share blood.

Manumission papers were drawn in August.

Effective upon arrival in Massachusetts, my father said.

Until then, the law says you belong to me, though you and I know better.

Elias stared at the ink as if it might evaporate.

Can I touch it? Soon enough, my father said.

For now we keep walking through these narrow gates.

Two weeks later we left under a pewter sky: carriage to Fayetteville, riverboats and roads through Virginia and Maryland.

At inns I was permitted upstairs.

Elias slept in stables.

In Pennsylvania my father exhaled as if air had found his lungs again.

Boston smelled of salt and coal and argument.

A Quaker landlady admitted us without flinch.

The courthouse clerk raised his brows at the papers, then stamped.

Congratulations, he said dryly.

You’re a free man in Massachusetts.

Best stay where the paper means something.

Three days later we married in a whitewashed church with no flowers.

Our landlady witnessed.

My father stood like a soldier in unfamiliar terrain.

Elias wore a borrowed coat.

I wore my best traveling dress.

“Do you, Clara, take this man?” the minister asked.

“I do,” I said, and something uncoiled in me.

“Do you, Elias, take this woman?” “I do,” he said, and reverence lived in those words like air.

“You belong to no man now,” my father told me afterward, pressing my hand.

“Not even to me.

Remember you chose this.” He turned to Elias.

Take care of her.

With my life, Elias said.

My father left the next morning.

We rented two rooms above a cooper’s shop in the South End, in a building that held Irish families, Black families, thin walls, and hope.

The stairs were narrow.

Elias carried me up and down.

We opened a forge, small at first, near the docks.

He rebuilt the hearth.

I painted a crooked sign: Gray & Ashdown Ironwork.

He protested the &; I insisted.

Without the books, there is nothing paid.

Without your hands, there is nothing to pay for.

Let the sign tell the truth.

Work came.

At first because he was strong; then because he was honest.

Some men made jokes that curdled the air.

Elias did not answer them.

He let work be his argument.

Women looked pitying or awed or both.

You must be very brave, one whispered.

No, I said.

I was very tired of other people writing my life.

Evenings we scrubbed soot and ink from our hands, ate stew at a wobbly table, and slept like spent tools.

Love did not arrive with trumpets.

It cooled into shape from repeated strikes: the way he asked consent even to adjust a blanket; the way he listened to Cicero as if ancient law might matter to a Blacksmith and a woman in a chair; the way he sounded out poems by candlelight because he wanted, he said, to put better things in his head than curses.

One January night in 1856, with snow pressing the windows, I interlaced my fingers with his and said aloud what the room already knew: I don’t know what the world calls this.

I call it home.

He bent carefully and kissed me like a man testing iron to see if it had cooled enough to touch.

We learned to handle the heat the way we had learned the forge’s—by attention, patience, and respect.

Boston wasn’t always safe.

We barred the shop door when mobs gathered.

In October 1857 our daughter Ruth arrived—tiny, furious, alive.

I named her for the promise, where you are, I will be.

Three more children followed: Samuel, Anna, Jonas.

Each birth was an argument against men who had turned my body into a prophecy of lack.

War came.

On paper, slavery trembled.

In our shop, iron still needed shaping.

The Emancipation Proclamation was read within earshot.

Free men and fugitives listened, shouted, wept, or stared straight ahead.

Does this change anything for you? I asked Elias.

On paper, I’ve been free since Boston’s stamp, he said.

Maybe it means more people will one day pay for their bread.

My father wrote in cautious codes from North Carolina.

Cousin James joined the Confederacy.

Soldiers trampled fields.

After the war, my father, old and stubborn, traveled north.

He stood in our narrow brick house and looked at the widened doors, the polished handrail, the map tacked to the wall.

You built this, he said—to both of us.

He watched Ruth recite geography, Samuel admire machines, Anna print, Jonas count and write.

On his last day, he sat at our table and confessed without preface: I chose this for you out of fear.

Not enlightenment.

I feared leaving you to those who would not see you.

I was wrong about many things.

I was not wrong about him.

You are more yourself here than you ever were in that walnut chair.

Because you demanded his freedom before his protection.

Because you claimed your voice.

I thought I was clever with papers.

You were wise.

He died two years later, and cousin James inherited the wreck of Ashdown Grove.

I received a box: ledgers, the manumission copy, a letter in my father’s hand.

If I am remembered, let it be for placing my faith in two people everyone said were not worth the trouble.

In 1871 Elias forged braces for my legs.

He had studied the way my hips and knees moved, sketched hinges and clasps on scraps.

The first time he buckled them on, my heart pounded harder than on my wedding day.

Lean on me, he said.

I stood, clumsy and weeping, and walked—ugly steps that felt like crossing a sea on dry land.

You gave me freedom twice, I told him.

Once on paper.

Once in my bones.

You were always free in ways I wasn’t brave enough to name, he said.

I just built tools.

We grew older.

Ruth taught Black children on Beacon Hill.

Samuel tinkered and patented improvements.

Anna married a printer who kept arguing in ink that law without practice is only half a promise.

Jonas kept the books and wrote essays under a pen name that no one guessed belonged to a dark-skinned man with a head for numbers.

Our house filled with grandchildren’s voices.

The sound of their feet became my new favorite music.

In 1891 an earnest woman from a historical society knocked and asked to record our story “for the record, for the future.” People like you fall through cracks, she said.

We let her read what the law had written and what we had written in its margins.

We made her promise to include the wheelchair, the forge, and the fact that love does not fit in pamphlets.

I died on a rainy evening in March 1896.

Elias sat by my bed, his hand around mine, warmth I had held for forty-one years.

Do you regret it? he asked, because he never feared my answers.

No, I said.

I regret only that I won’t see our grandchildren read the words we put in our heads and know they exist because we refused to live by other people’s fears.

Rest, Clara, he said.

I’ll be along soon enough.

He was.

Three days later, in the chair beside my empty bed, his head bowed as if in prayer.

The doctor wrote “heart.” Our children wrote “hers,” gone ahead and taken his with it.

We lie together on a Mount Hope hillside beneath a simple marker: Clara Ashdown Gray 1833–1896.

Elias Gray 1826–1896.

Forged together.

A century on, a researcher in a Boston reading room opens a brittle page in my hand.

The ink is faded, but I hope the heat still lives in the words.

If something in you stirred—if you felt anger at laws that boxed us in, tenderness for the girl in the walnut chair and the man called Goliath until someone finally called him husband—you have joined our argument with history.

Under the romance and improbability, this is an argument: that disabled does not mean disposable; that enslaved does not mean incapable of thought or tenderness; that a father raised on ledgers can choose his child’s wholeness over his reputation; that a scandal, carried with courage and stubborn love, can become the best thing anyone ever did.

If you carry that into your own choices—if you look at those the world calls not worth the trouble and see instead the iron waiting to be forged—then our story has not ended with names on stone.

It continues every time someone refuses to live inside the smallness of other people’s expectations.

News

The Profane Secret of the Banker’s Wife: Every Night She Retired With 2 Slaves to the Carriage House

In a river city where money is inked but paid in human lives, the banker’s wife lights a different fire…

The Plantation Lady Who Locked Her Husband with the Slaves — The Revenge That Ended the Carters

The night I decided my husband would go to sleep on a slave’s pallet, the air over Carter Plantation felt…

The Pastor’s Wife Admitted Four Women Shared One Slave in Secret — Their Pact Broke the Church, 1848

They found her words in a box that should have turned to dust. The church sat on the roadside like…

The Paralyzed Heiress Given To The Literate Slave—Their Pact Shamed The Entire County, Virginia 1853

On the night the county gathered to watch a girl be given away like broken furniture, the air over Ravenswood…

The Judge’s Daughter Who Secretly Married Her Father’s Favorite Slave—The Trial That Followed, 1851

They said the courthouse had never held so many people. The air felt like wet wool—heavy with perfume, sweat, and…

The Plantation Lady Replaced Her Husband’s Heir With the Cook’s Slave Child—Georgia’s Silent Scandal

They say the storm that broke over Merryweather Plantation in the spring of 1854 was the worst anyone in that…

End of content

No more pages to load